Rashid Johnson was just 24 when his work was picked up for the landmark 2001 exhibition Freestyle at the Studio Museum in Harlem, an exhibition of 28 notable young African-American artists. It was Rashid Johnson’s photographs that sprung him to international art world fame aged just 24; his 2001 series of documentary portraits of Chicago’s black homeless population placed him at the forefront of his generation of African-American artists. But any exhibition of his is just as likely to include painted masks, shea butter sculptures, tropical plants or wallpapered collages as it is the photographic works that made him famous.

Though born in Chicago, he’s lived in New York for the last 20 years, a natural base from which to expand his highly personal interrogation of the intellectual and creative history of African-American culture. It therefore seems somewhat strange to be heading out into the heart of the English countryside for lunch with Rashid at Hause & Wirth’s Somerset gallery. Somerset’s sprawling fields and picturesque hay bales feels as far as it’s possible to get from New York.

Rashid’s new exhibition at the gallery, Stranger, is the result of a two-month residency that saw the artist transplanted from the States to the small town of Bruton; an absurdly picturesque English idyll. In the sun, smoking casually and smiling, Rashid looks relaxed. “Coming from New York, it was an interesting way to be. There’s so much familiarity, and you are this person who is different in so many ways,” he begins. “For instance, I’m the tallest person here,”he laughs. “And that’s not the only difference that I have from many of the people in the town…”

Stranger is taken from James Baldwin’s 1965 essay Stranger in the Village, in which he recounts his experiences as a young African-American man living in a small village in Switzerland. “He’s thinking about his foreignness,” Rashid explains. “For me, I’ve had a lot of opportunity to travel internationally. We’re living in a global world; the internet and communications have led to us having less distance than say, 1965. But strangely, I show up with all this experience and I realise still that, in a lot of ways, I felt like a stranger.”

These points of difference are unpicked by Rashid throughout the show, in works that make use of materials like shea butter and West African black soap. Both are products that were used in his own family home but speak to a wider dislocation experienced by the African-American community and the symbols that connected them with home. Rashid is going to place black soap in the gallery toilets for the duration of the show alongside a soft hunk of shea butter to touch and rub onto your hands. It’s a gesture of participation, breaking down the boundaries between art and life, artist and audience, and of course an art gallery and its loos.

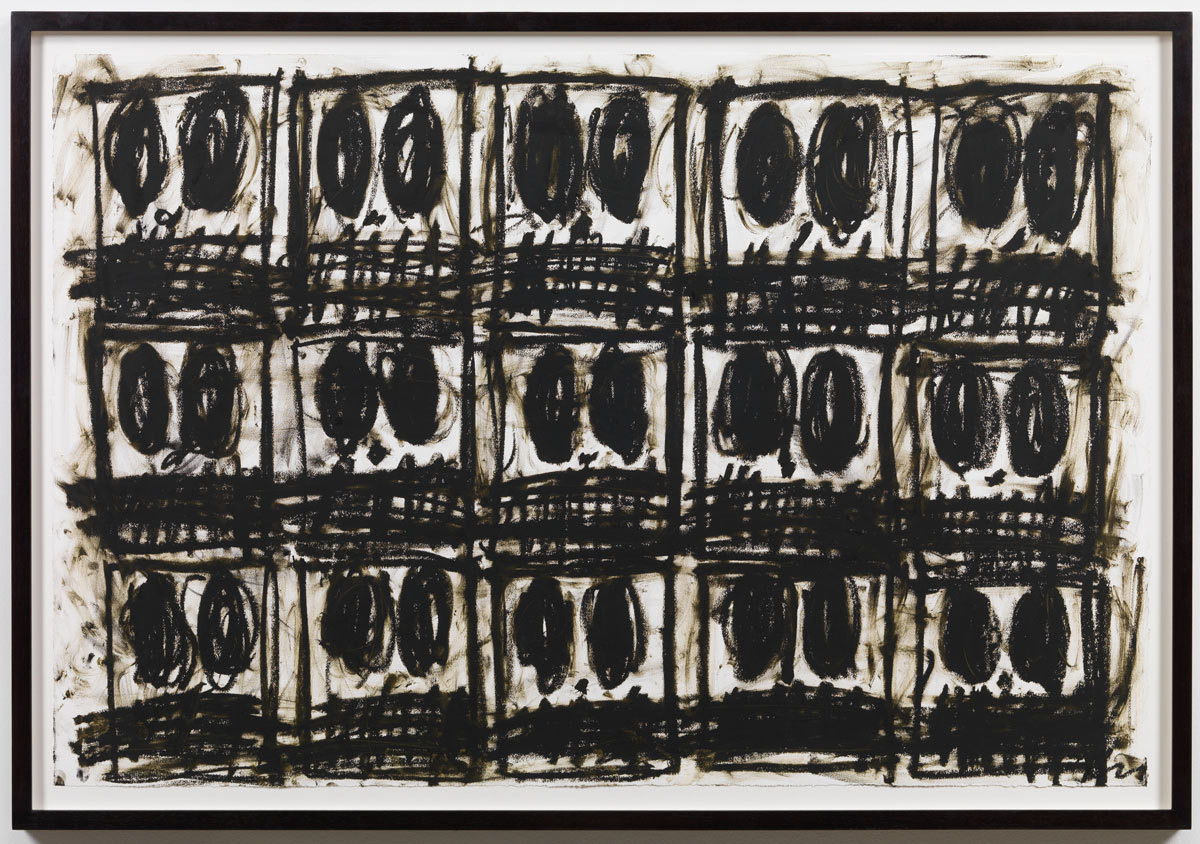

Second-hand copies of many of Baldwin’s books are stacked inside the entrance to the gallery, collected by Rashid and available to borrow. And books can also be found amongst a series of immense steel gridded structures, or nestled between potted tropical plants and shea butter sculptures with wild faces gouged messily into them. There are copies of The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual by Harold Cruse, The Sellout by Paul Beatty and Camus’ The Stranger.

Their titles are direct, touchstones that Rashid responds to. He’s interested in how found objects create personal, racial and cultural identities, and how they’ve shifted in the digital age. “I often think of myself as a pre-internet artist, but I’m in fact very much a post-internet artist,” he states. “A lot of the materials I use in my work, I find online. Making things more accessible has had an incredibly positive effect on how I function as an artist. Everything’s become way more deconstructed, you choose your own sources. You create your own version of pop.”

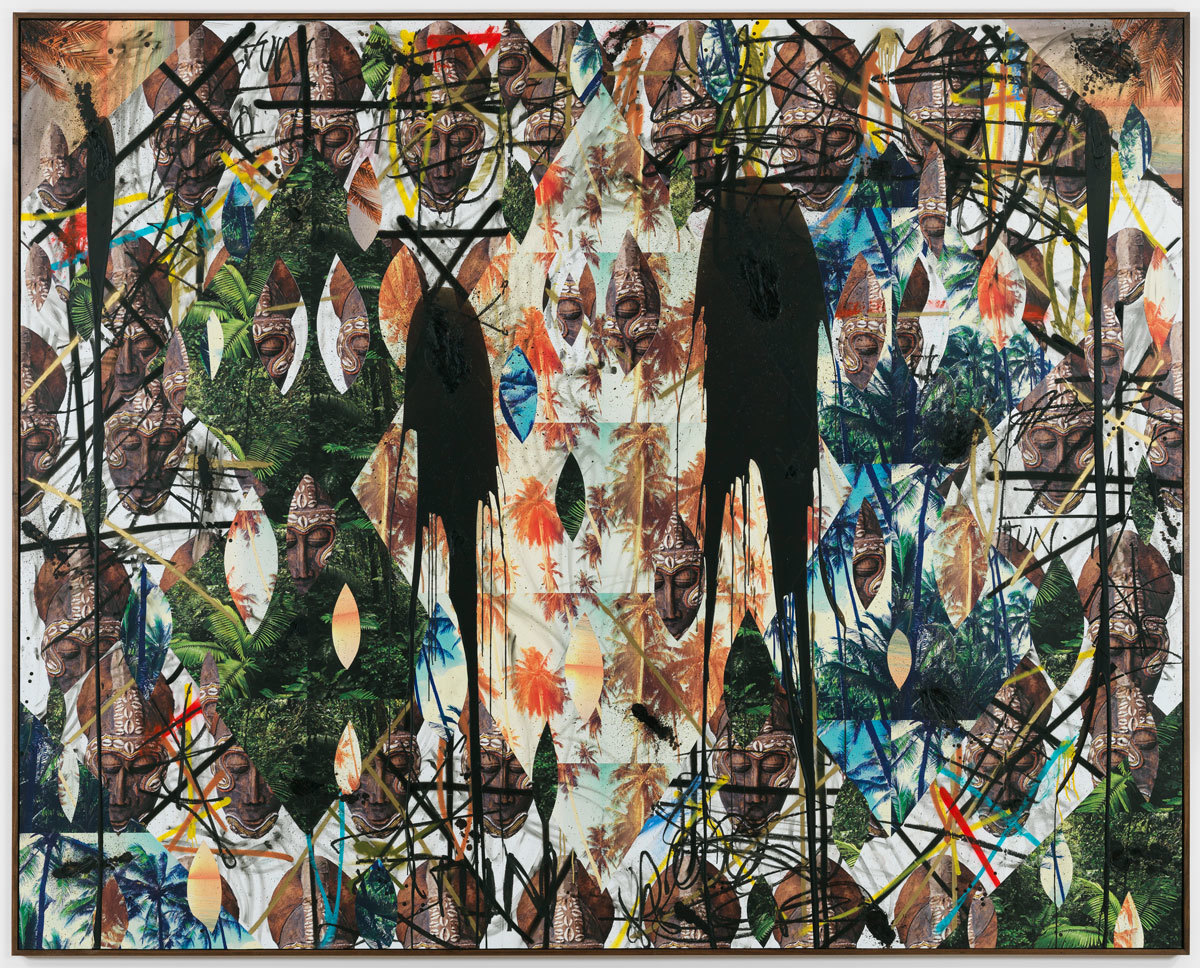

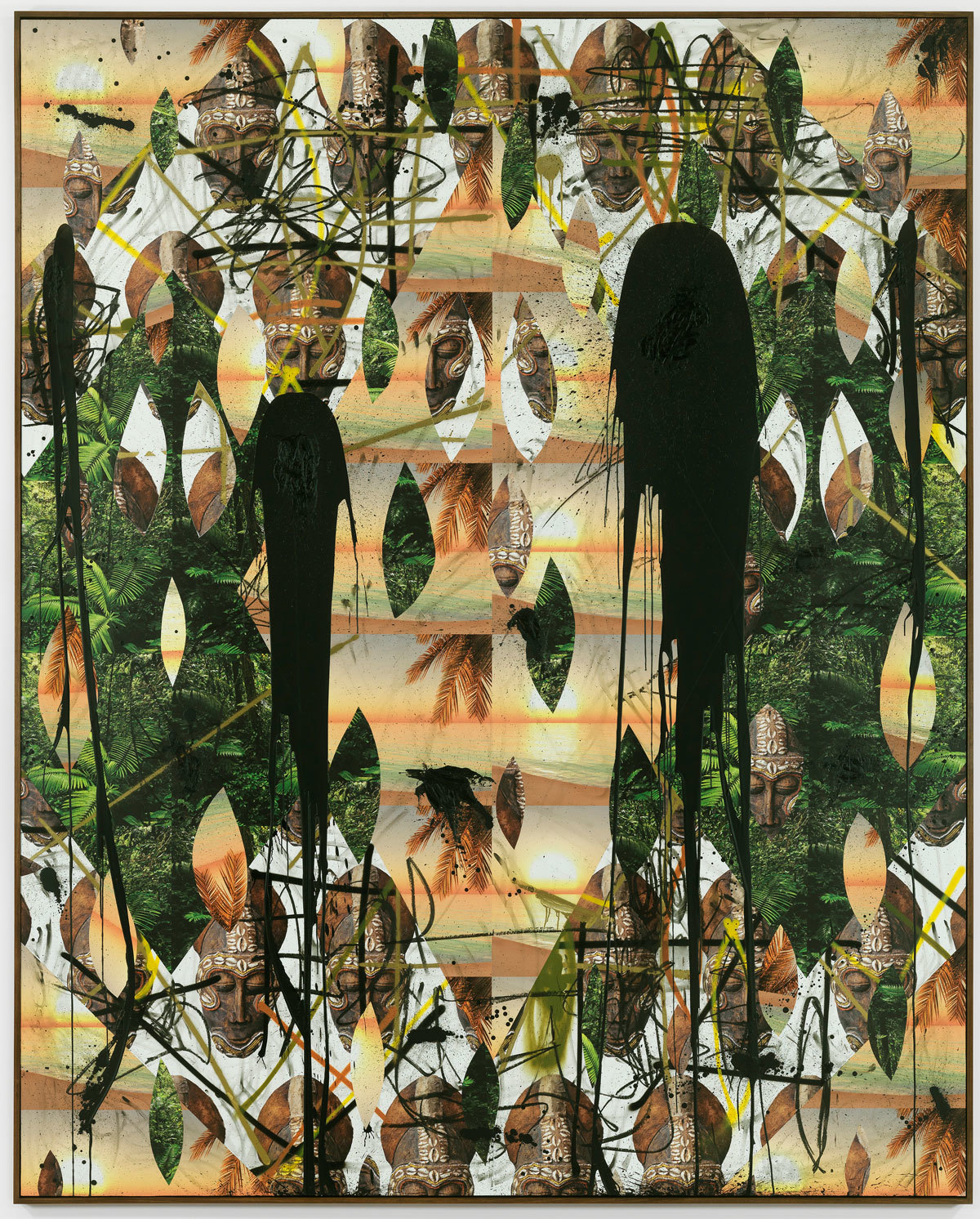

Rashid’s own pop perspective comes through most clearly in his collages. Densely layered with traditional African masks, lush greenery, palm fronds, turquoise waves and postcard-perfect beach sunsets, they are flattened into images that look almost like wallpaper from a distance. Motifs are repeated, creating diamond-shaped patterns that dance across the wall. They are pretty. The sunsets and palm trees are saccharine sweet, lifted from tacky T-shirts into Rashid’s collages. But the aspirational visions of tropical paradise cut away and intersect to orchestrate what is hidden and what is revealed. Eye-shaped sections are pulled away to show thick smears of shea butter below. Black soap and wax are daubed over the top of the images to form dripping spectres that linger long in the mind.

The works span pre and post Trump America. I wonder what impact the seismic shift in American politics has had on Rashid’s work. “At times like this, artists are affected in the way we all are. I still feel very shocked. This body of work speaks to a graduation from anxiety to shock,” he says. “I’ve always dealt with themes that have touched on politics, place, identity, who and how we are. More than ever the work is about oppression. It’s about fear and insecurity at a time when these things are present in all of our lives.”

Standing in the heat beside the tropical plants of the exhibition, the English countryside spread out all around us looks less familiar, as Rashid points out, it’s increasingly difficult to recognise the world that we live in today. In a few days he’ll return to New York, but his works will remain on the farm throughout the summer, a foreign presence with the power to alter how each of us relates to the world around us. He makes us remember what it is to be a stranger not only in a foreign land, but in a familiar one.

Credits

Text Louise Benson