Writer, lecturer and self-confessed “goddess-at-large” Reba Maybury orbits a world filled with some of London’s most colourful subcultural characters, so post her Radical People release in 2015, it felt only natural that one of her friends became the subject of her new project. Inspired by drag artist Max Allen’s singular approach to dressing and expression, she has penned Max Allen Loves Experimenting With Different Clothes; A Portrait Of A Modern Man, which sees drag artist Max is brought to life through stories, interviews and accounts from London’s queer scene favourites including sculptor Prem Sahib, alternative drag artist Jonny Woo, visual artist Eddie Peake, make-up artist Daniel Sallstrom and i-D’s own Culture Correspondent Princess Julia.

Reba explains, “behaviour, action and making work are the elements of ourselves that will be remembered, not our digital identities. For me Max personifies a reaction to a lot of beige happenings in culture right now, so I wanted to celebrate him in a way which challenges our social media norms – making a book about an individual is what a lot of people desire but Max rejects a banal form of popularity for the sake of making his passions electric.”

Ahead of its release at Donlon Books on Thursday evening where Max himself will be on hand to sign the 69 copies for sale, we asked Reba to share an exclusive excerpt that that chronicles their first meeting at Saint Martins, what it meant to her and what makes Max Allen’s energy so essential.

‘Anger is an Energy.’ – PiL 1986

I first saw Max Allen in a fashion magazine when I was 18. It was the initial edition of an obnoxiously smug publication, run by people who still think that they are still as cool as they were in 90s and that sexualising aristocratic teenagers is great. Within the drab of sensationally unconcerned pages appeared an editorial comprised of portraits of then-current Central Saint Martins students, taken inside the Charing Cross Road building – and this small editorial instantly jolted the magazine into something more human. While the fashion industry is essentially a business of unattainability, sustained by the idea that you can never achieve what it is offering, these photos were honest.

When I first saw these portraits I was still living in the town I grew up in, and I was desperate to move to London and start at Saint Martins. I knew that this historic art school would offer me something significantly more diverse than the village I grew up in: a place where I would meet people who were as eager as I was to discard the monotonous expectations of my provincial surroundings.

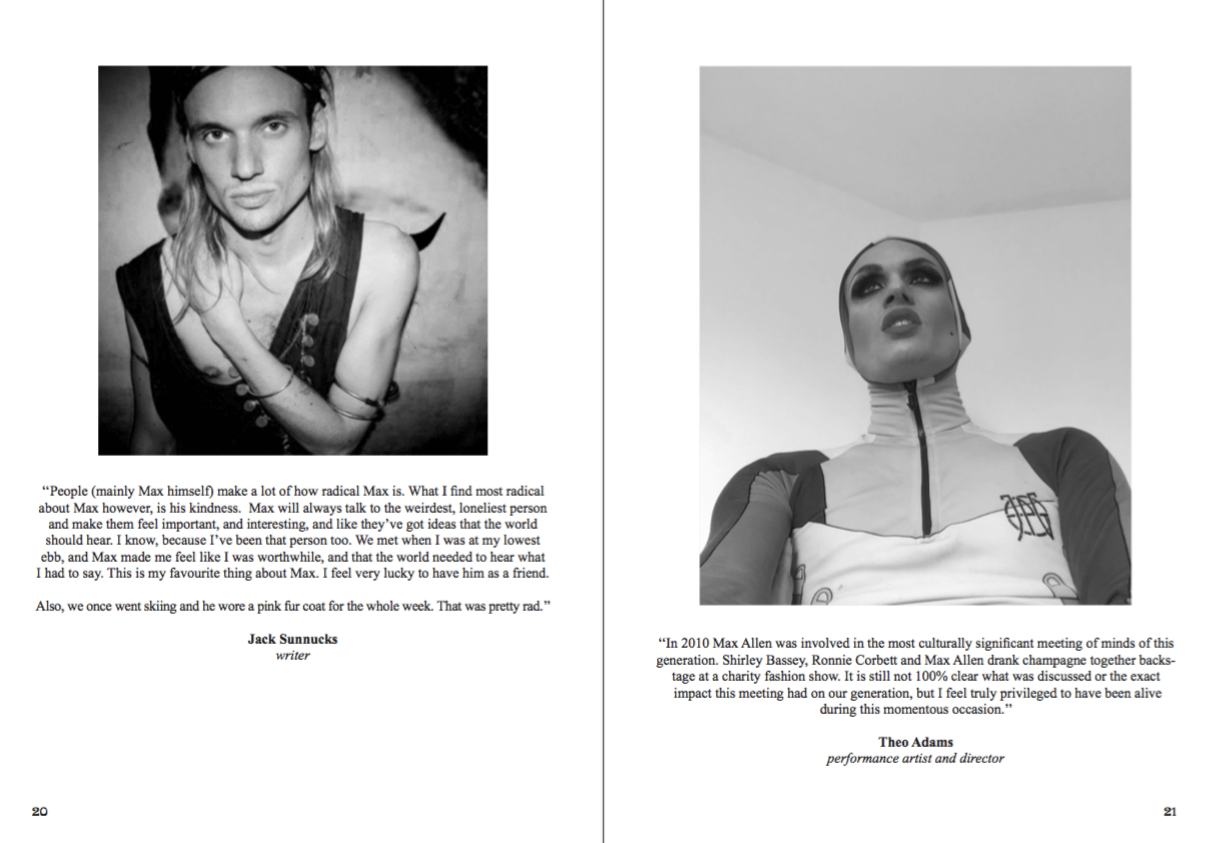

Back then, Max Allen was in his first year as a fashion design student. He wore 1970s mens platforms with a trench coat, his hands placed on his hips. In comparison to how he now dresses – mixing the most perverse selection of prints, textiles and slogans together – he looked almost subtle, but to me he was the type of individual I’d been dreaming of meeting. It wasn’t so much to do with what he was wearing, but more to do with how he looked at the camera: with a ferocity that dictated he knew who he was.

This wasn’t the first time that Max had had his portrait in print. While studying for his BTEC in fashion at Chesterfield College a few years before, a local newspaper had shot the clothes he’d been making because he’d printed them with Indian swastikas. The caption to that portrait read ‘Max Allen Loves Experimenting With Different Clothes.‘ That spoke volumes on the future Max would have.

Where myself and Max were lucky enough to experience the last days of Saint Martins in its original building, while Labour were still in power, six years later fees have tripled, grants have disappeared and the new campus has found a home within a building site that resembles a bank far more than the place where the Sex Pistols played their first ever gig. The landscape of this radically developed area has become a capitalist dystopia of cranes, rising lifeless apartment blocks and restaurants made by millionaires aimed at the people who can afford to buy these grey homes.

I recently taught a class of fashion students at Saint Martins and asked them who they thought was the best dressed person that they knew or admired. The room went silent as the students squirmed in their jeans and said that it was a hard question to answer. I always believed that fashion was pleasurable because it was so personal: getting dressed is an action that can enable the intricacies of communication with like-minded people. At least, that is what Max said to me when I first saw him in the Saint Martins hallways: he commanded an unspoken respect as someone who didn’t need to open his mouth to communicate what he believed in. He takes the daily activity of putting on clothes and turns it into an art form. Fashion is powerful and, in an age where the word ‘normcore’ actually has agency, Max’s energy is essential.

Terms like authenticity and subculture get knocked around so much that it almost feels like their power has solidified into a mili-fracture of their intoxicating meaning. Born in 1989 in Sheffield and living in London for the past eight years, Max has solidified himself as a true English eccentric: an individual who defies categorisation with a powerful magnetism.

It could be easy to group Max into a box – a drag queen, a club kid or a personality – but within a culture that nurtures the ‘creative career’ with a capitalistic vision, he rejects these quasi-independent barriers with glee.

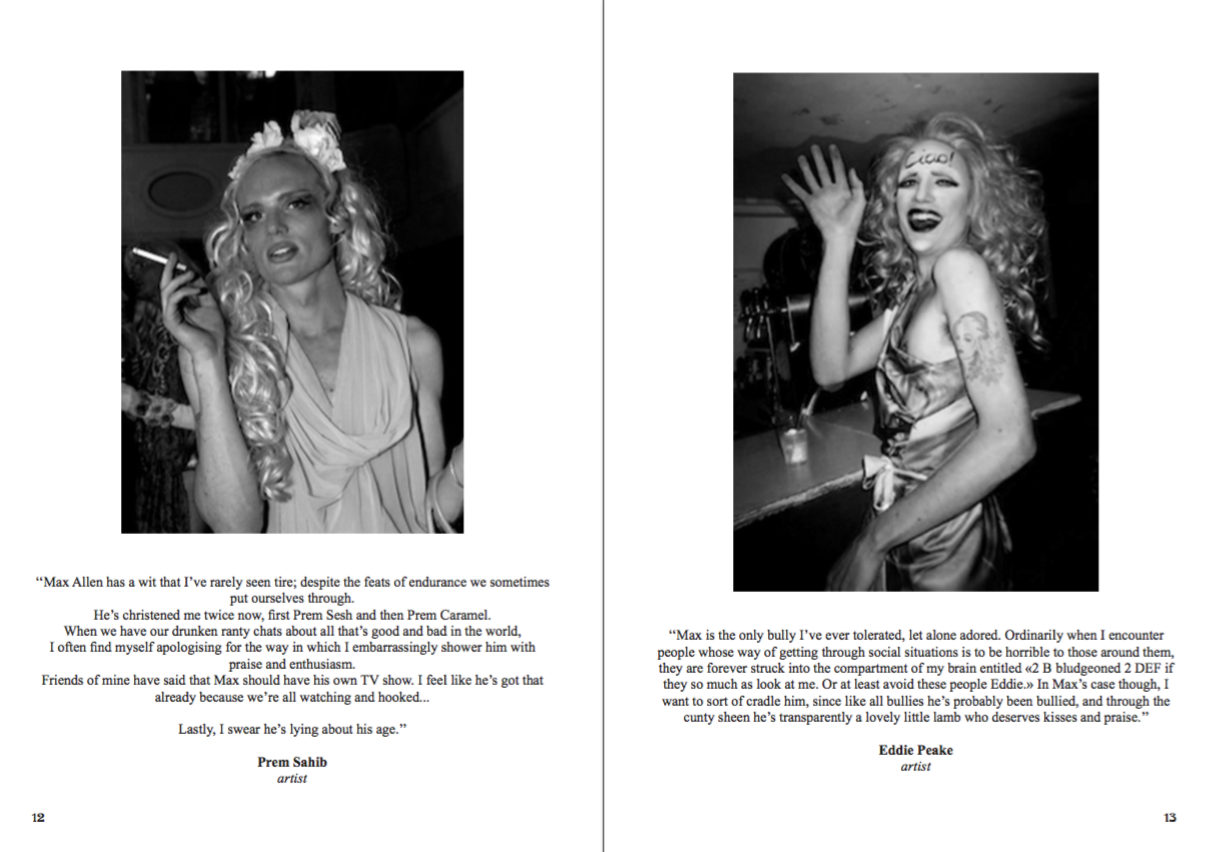

‘The world of heterosexuals is a sick and boring life‘ was stated in John Waters essential film Female Trouble (1974), and Max’s outstanding visions of drag incorporate everything that Waters hoped his legacy would have inspired – but mixed with the cruelest of British sarcasm. On Halloween a few years ago he dressed as a ‘sexy Mr Blobby,’ subverting the ludicrous nature of women dressing as sexualised cats, nurses or witches intertwined with one of Britain’s most ridiculous pop culture characters.

Max Allen borders on the politically incorrect – and in many ways he is completely incorrect, because he doesn’t accept the way capitalism demands a manipulation of two of his biggest passions: getting dressed and having fun. At a recent party thrown in celebration for ‘London’s young creative community’ by a Murdoch-owned newspaper, he arrived with a patch on the back on his jacket that said ‘FREE DRINKS WON’T PAY OUR RENT’. He is fearless and argumentative, and he is frustrated by the way that the creative arts praise entrepreneurial concepts. Like a modern day David Wojnarowicz, who brandished the epithet ‘If I die of AIDS – forget burial – just drop my body on the steps of the F.D.A’ on his coat at an ACT UP protest in New York in 1988, Max is talking about something that many don’t want to acknowledge, a fearful respect for the people who have money but not necessarily any taste or respect for artists lives and work.

Like anyone with a strong point of view, he can seems off limits, angry and confrontational, but when was the last time you questioned the fact that the abundance of sold out British music festivals create fun for people rather than encouraging people to make it for themselves? And that they are being headlined by artists with names such as ‘Florence’, ‘Mumford & Sons’ and ‘Sam Smith’? Actually, let’s re-iterate this; Glastonbury, a festival of profound cultural history and integrity is this year being headlined by ‘Muse and ‘Coldplay.’ And that, simultaneously, queer spaces across the country are being shut down with reckless abandon? The year is 2016, the Tory government is well and truly alive and kicking, and it’s punching right into the heart of controlled enjoyment.

Walking through Shoreditch or Dalston on a Friday night is now an experience of guttural male aggression, bankers snorting coke in alleyways, stag parties leering and barking at any woman that walks by and West London tourists using the once-rebellious streets as a weekend playground, leaving their hedonism on a Sunday morning on the piss stained streets. Queer spaces have historically been the genesis of countless formations of essential rebellion, established with the focus of making the world more compassionate – but now London washes these safe spaces out for the wealthy and tasteless.

Max Allen hates you. He doesn’t necessarily hate YOU, per se, but what he does hate is mediocracy, people who accept boundaries, people who don’t question conformity… especially those young gay men who hide behind plastic screens and only allow their cultural tastes to dive into the shallow waters of RuPaul as a signifier of their subversion.

Jean Genet famously said that ‘to achieve harmony in bad taste is the height of elegance.’We could speak for hours about how we determine what bad taste is, but of course taste is completely personal, specific to your social and economic background. However, let’s focus on a few of our contemporary fashion zeitgeists: Vetements, a clothing brand that celebrates physical comfort and is worn by white models mimicking the clothing worn by working class people of colour and Loverboy, a nightclub-cum-clothing brand using the injunction of a thirty year old ideology that languishes under the comfort of hazy nostalgia. If bad taste is a rejection of the mainstream and the solace found from fitting in, Max Allen takes this construct and sabotages it through his wildly blunt Facebook statuses and outfits that clash and morph into unknown paradigms of chic vulgarity.

Reminiscent of the Warholian idea that the personality can be a piece of work, Max Allen exposes the truths – particularly those in London. In London, a city where blandness is so often dressed up as innovation; a city where subculture is served up for sponsored events disguised as edgy happenings; a city that lures us into the false security of a salaried job while giving a head start to those from financially comfortable backgrounds.

As more and more young, innovative and honest fashion designers face bankruptcy before the age of thirty simply because a consumeristic business model fails to embrace creativity, the idea of just ‘doing it yourself’ is becoming increasingly realistic. This is what Max has always done: he makes his own clothes for himself, recycles pieces given to him by friends, recontextualizes those found in charity shops and makes them completely his own. He creates his own sexuality, his own understanding of attractiveness, his own concept of fun and his own ideas of art.

Max Allen is an individual and he is completely human. In a city that is so rich – both economically but also culturally – yet is apathetically ignoring the cloud of stagnant money engulfing it, it is Max’s resistance to conform to any ‘creative career’ or gay stereotype that cements him as so original. Which is why this book is dedicated to his essential rebellion – a life as art.

Credits

Text Lynette Nylander