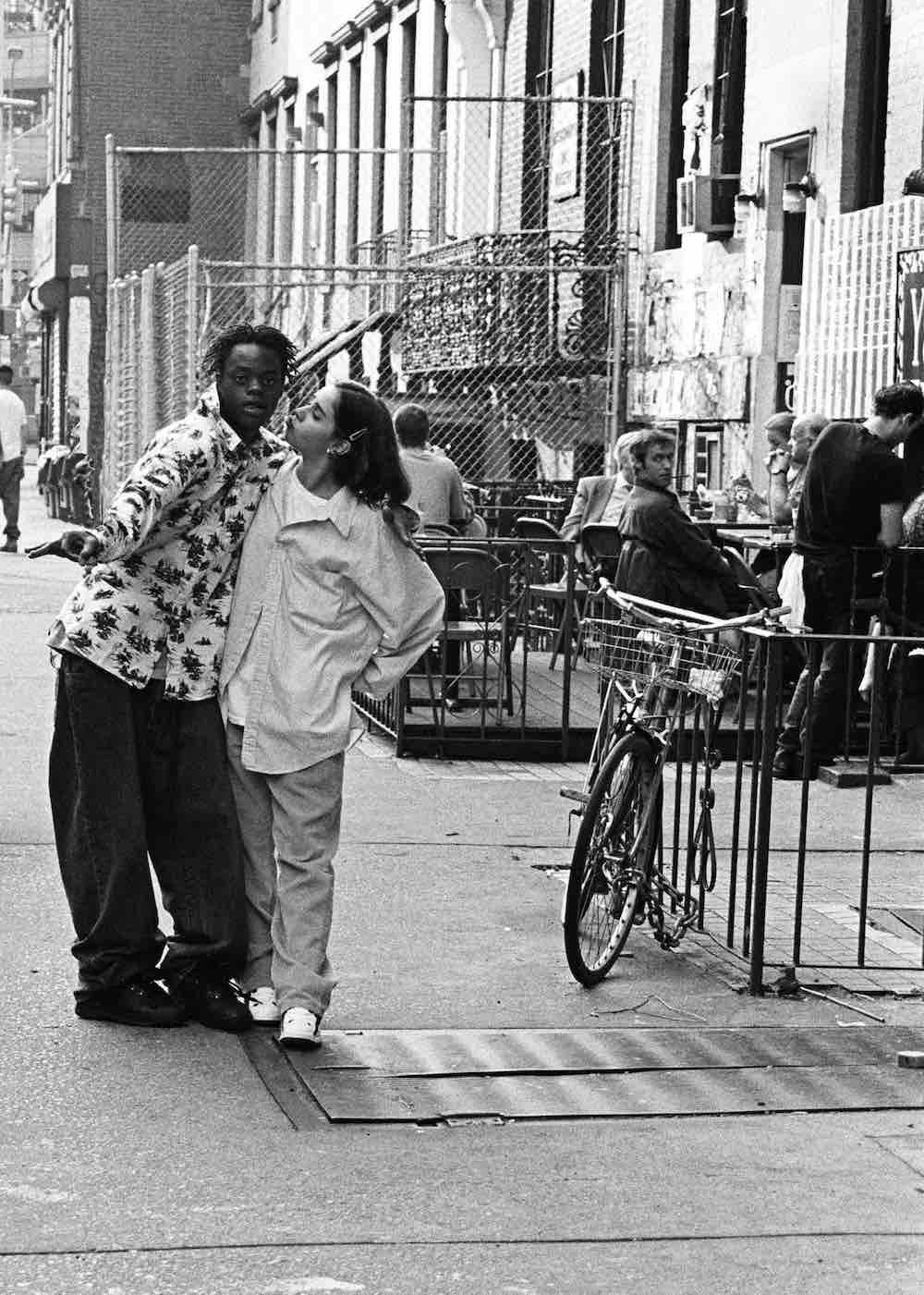

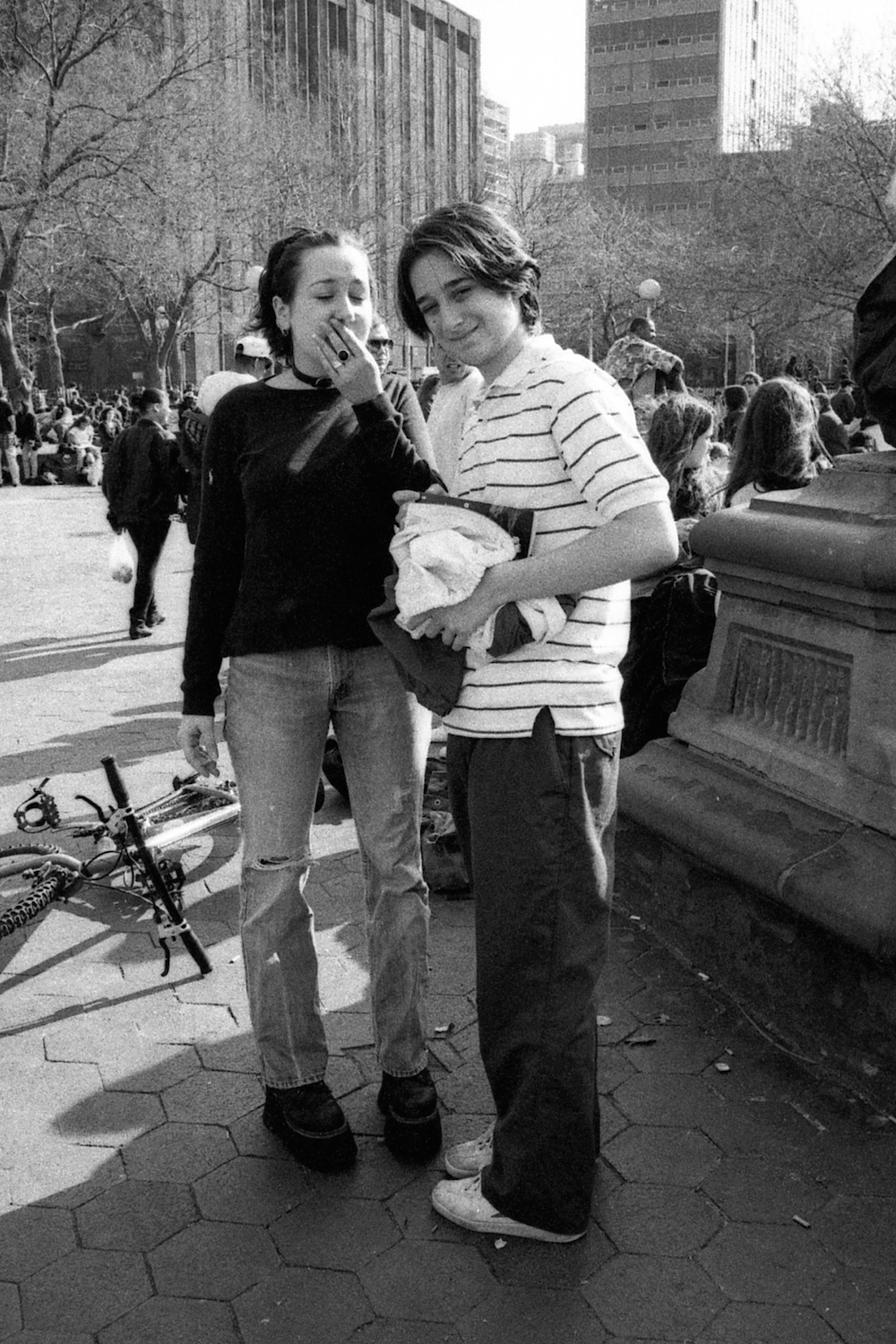

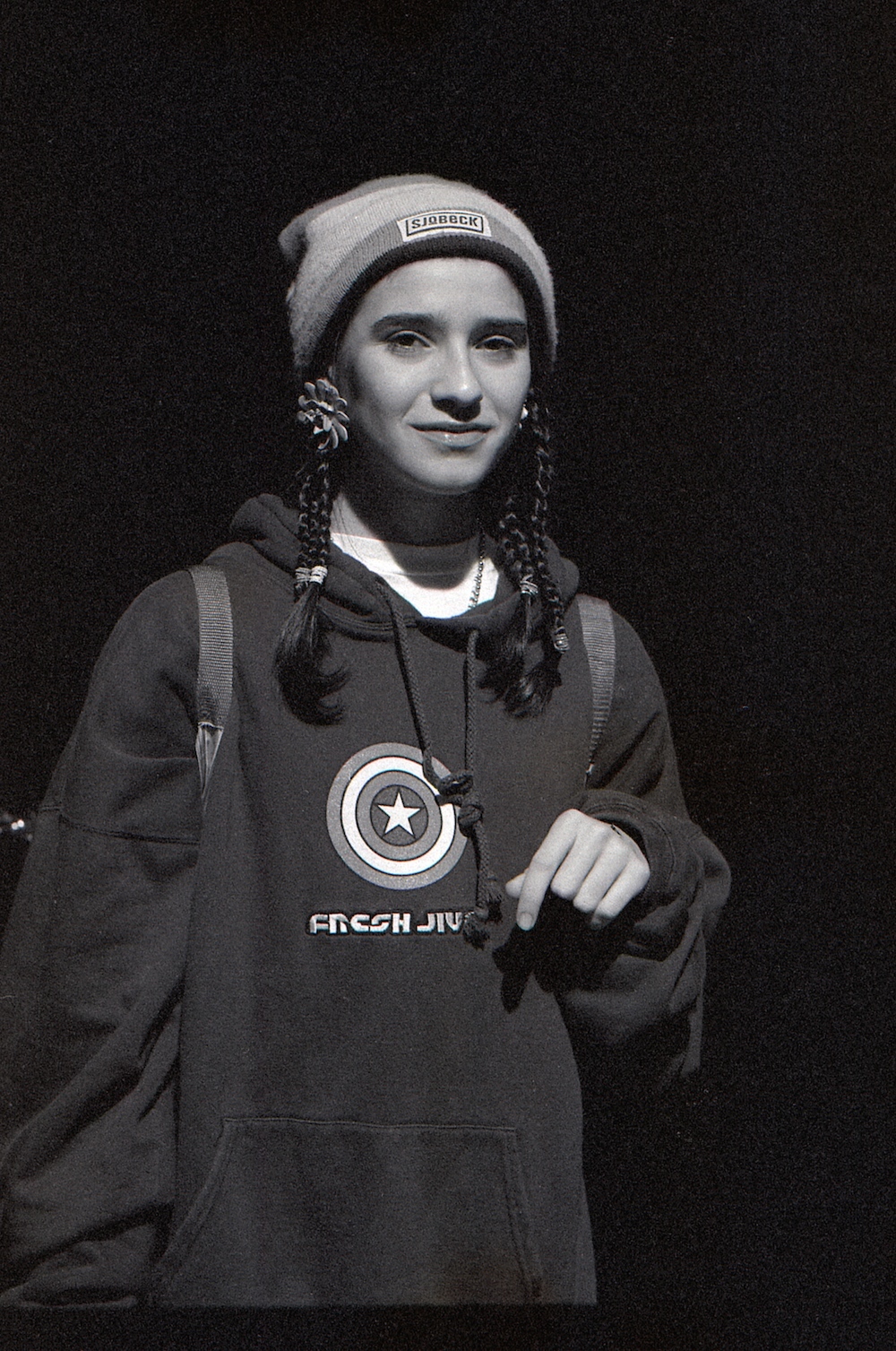

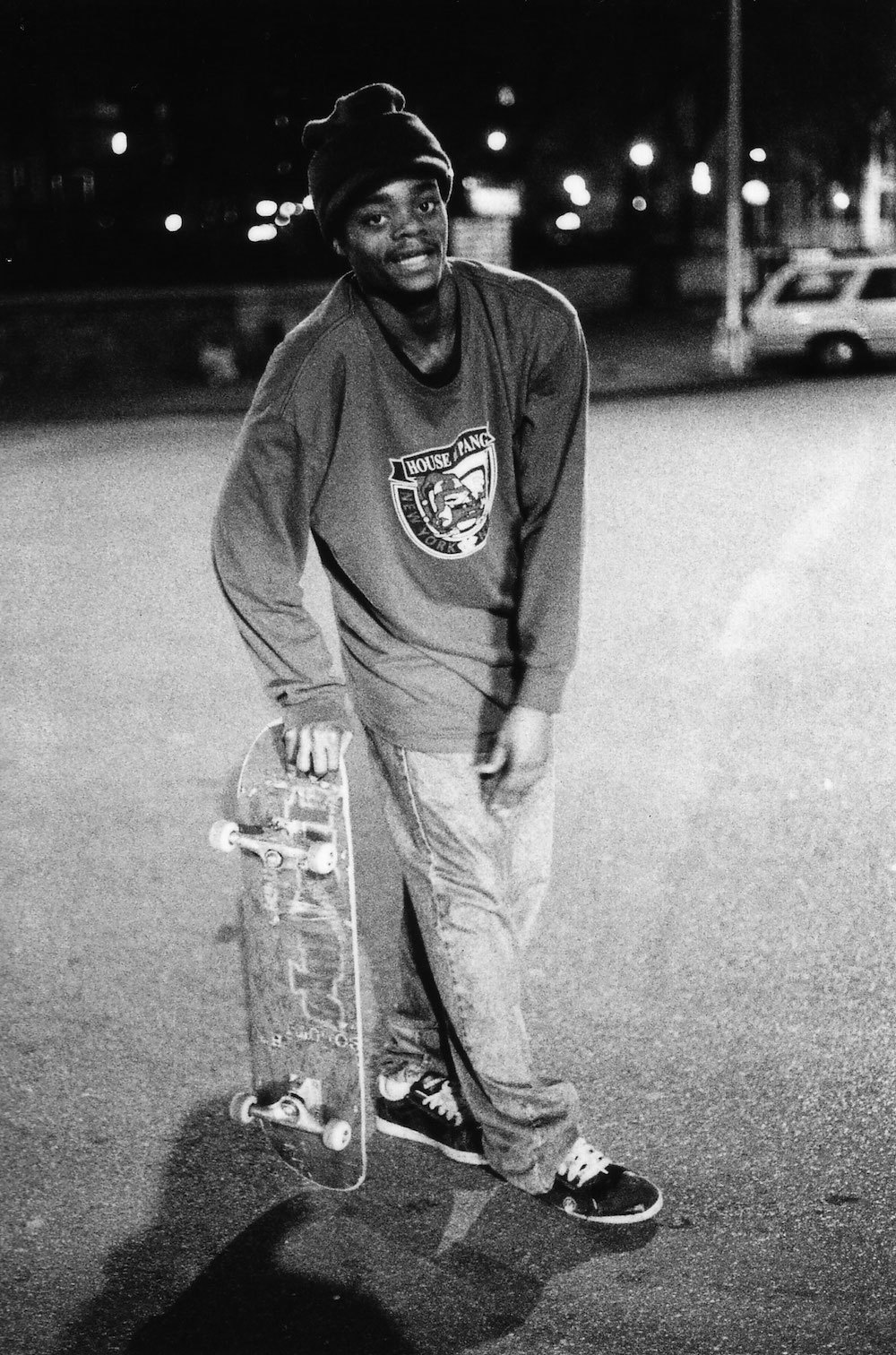

New York’s relentless impermanence has long compelled its residents to document not only their neighborhoods, but also their lives. To say: this is who I am, this is what I did, these are the people I love, and often, the people and the places I’ve lost. I think of Nan Goldin, whose late-80s love letter to her queer tribe is both immensely personal and political. I also think of Ash Thayer, who spent eight years squatting on the Lower East Side in the early 1990s, and documented her community in the spaces it created. Or of Jamel Shabazz, who made joyful portraits of empowered black youth in his native East Flatbush throughout the 80s. And I think of Mel Stones and High, the best friends who captured their tight-knit crew of skaters and the downtown they roamed throughout the 90s — the twilight of old New York. After nearly 25 years, the pair’s black-and-white photographs are now being published, in a brilliant new book called That’s a Crazy One.

Mel was born in Sunset Park in the late 70s. “It was dangerous, but I was a street kid. My parents were like, ‘Go out, have fun, just don’t die,'” she recalls with a laugh. “I had a lot of freedom, and I was always on the street.” She met High, who grew up in on the Lower East Side, during her freshman year of high school in the early 90s. High went to Stuyvesant, Mel was at Brooklyn Tech before transferring to Lincoln, a Brighton Beach high school that had an excellent photography program. “I had a really cool teacher who would give me free film as long as I’d shot it by the next morning.” So both she and High began carrying their cameras everywhere; capturing skate sessions, blunt rotations, and hangouts at High’s place on St. Mark’s Place.

is arranged chronologically, compiling photographs taken throughout the 90s — one of the most transformative decades in New York City’s history. The early days show a more punk side to skating, before hip-hop exploded and the rave scene became more popular. “In Washington Square, you had skaters, punks, goths, ravers, nerds. I guess the best way to describe it is that we were all outcasts to anything that was regular,” Mel says. She mostly rolled with the skaters, then a very small crew who posted up at Astor Place. Everybody knew everybody, but it didn’t feel insular. “Our social group was really dynamic; we all vibed off each other. I don’t think there was this really strong need to identify; we were all just happy to be exposed. People were just trying to survive and get by, and having to be anybody wasn’t really a priority. We were just being ourselves, and that’s I think what made it so cool.”

Some of the faces in their photographs have since become familiar ones, thanks in large part to Kids, the controversial film Larry Clark made about their lives and their city. Harold Hunter, Chloë Sevigny, Gio Estevez, Justin Pierce, and Harmony Korine (who asked High for guidance writing some of the female characters’ dialogue, despite their aversion to the film) all appear in the pictures. But here, we see them through the eyes of their own tribe, not as players in Clark’s harrowing, hyper-sexualized AIDS drama — a fictional film that’s often perceived like a documentary. Mel and High have spoken about the discrepancies between its characterization of their friends, and the people they really knew. But Kids did capture the last days of a New York that no longer exists. Like That’s a Crazy One, it is a window into a lost world.

As she and High prepare to launch the book and an exhibition of its photographs, Mel shares a little more about what that world was like.

Today, we live in a world of surveillance and instant communication. What it was like to be a young New Yorker before that?

I grew up in South Brooklyn. There was violence, there were drugs, and there was a real importance placed on being street smart and aware — knowing that dangerous situations could arise in the blink of an eye. I was very afraid; I was the youngest of four kids living in Sunset Park! But from a young age, I knew how to act. It was a poor city then. Now when I go back, I see how gentrified it’s become. I feel like a lot of people there now have watched too many movies about New York, have this perception of what it is to be a New Yorker, and carry around a certain attitude that doesn’t correlate with what a real New Yorker was. It’s not this portrayal of tough, everyone-for-themselves New Yorkers. When people are poor, they support each other. Locals, natives, they support each other.

And back then, there weren’t a lot of cops. Well, they were there, but they were busy with murder and huge amounts of drugs. The mafia was still around. So if you were a kid on the street and you weren’t doing anything really apparent, you weren’t really policed. I mean, we used to walk by the cops smoking a blunt; we sat on St. Mark’s drinking 40s all night. But we were a really tight crew of people that were always together, so we had that protection of each other. Growing up there was really free. But just like that, it went from [Mayor] David Dinkins and the worst crime rates ever, to Guiliani, who recruited thousands of new cops. We went from being used to not worrying to being over-policed and worried that we were going to get picked up for anything. It was a mind-fuck, because it happened when I was 17 or 18.

Nineties style has exploded in popularity these days, but much of it seems to be based on an idea of what people wore. These portraits capture a reality that’s much more interesting. What were you wearing then?

I was way more of a tomboy. I wanted to be comfortable and didn’t want to be sexualized. You couldn’t escape that machissmo on the streets; I’d get cat called at nine years old. And AIDS made sex terrifying because of what we were being taught in school. So I think girls’ style was more about androgyny — about not wanting to be a Barbie doll or the 80s heavy makeup and big hair. It was stripping that identity away.

High’s wearing a sick Supreme shirt in one of the photographs. What was the original Lafayette shop like back then?

There was a real lack of skate shops at the time, and when Supreme opened, it was the opposite of what a skate shop was. Gio [Estevez] had gotten a job there through High’s mom who knew James [Jebbia] because she worked at the flea market selling t-shirts with him. It was all very experimental. There were about 30 people who skated back then. If someone skated, you knew them. Gio was the most responsible one, so he got the job. It was the same people, the same family. Everything that Supreme promoted and how it started was based on the characters of our crew. They were the ones who pioneered street skating. There was no street skating; half of the tricks had never been done before. It created a multibillion dollar industry, streetwear, and everything that came along with it.

You and High are donating all of the book’s proceeds to the NYC Public Schools Art & Photography Program. Why?

Lincoln [High] is in Brighton Beach; it’s not a rich neighborhood. In high school, I wouldn’t go to my classes. I would only go to the photography lab because I was so in love with it. My teacher knew I didn’t have any money, and gave me that free film. It saved me, because it gave me a passion. If it weren’t for that inspiration and that push to create something, it would have been easier for me to get lost in how I was living, and the self-destructive things I was doing as a kid. [Photography] gave me something to land on. I loved it, and I still love it. I still get excited when developing a roll. We wanted to give back in that sense. This book wouldn’t exist without [Lincoln’s program].

A lot of our good friends have passed, and these images kind of lay in a box. In the end, putting them together ended up being a healing process. But I don’t think either one of us were quite ready to deal with reliving it. Ultimately, we just want to keep as much of [our friends’] memory alive as possible in a positive way. Some of the deaths were tragic, but at the same time, these were incredibly inspirational, wonderful, compassionate, inclusive people that had so many friends. They were like the glue. I think that if we can give something back, it would make them stoked. We did it to memorialize our friends and to make our yearbook — to say, “This is what it really was like.” And to give it some peace. This was our attempt to heal ourselves, and our friends.

Credits

Text Emily Manning