As far back as the 12th century, women in China were conscripted into the mutilating practice of footbinding. Young girls would have their toes broken and bandaged under the foot, so they could be forced into tiny, artisan-crafted, embroidered shoes. Later, women in Western societies had to contend with the suffocating constraints of corsetry. Contemporary physicians condemned the steel-boned undergarments as a severe health risk to women. In the Victorian era, thousands of women were killed as a result of their huge crinoline hoop skirts catching fire.

These examples highlight the historic trend toward incapacitation in women’s fashion. Patriarchal society designed clothes that would cripple and confine women as much as possible, rendering them incapable of working, exercising, or causing much trouble at all. This trend lingers today: women confess to feeling pressure to brave the blisters, pain and discomfort of heels in order to compete in the workplace.

But much progress was made in the Victorian era thanks to the dress reformers, who rebelled against misogynistic trends in fashion, and fought to normalise more practical, comfortable clothing for women. The bicycle fad of the 1890s, and the onset of WW1, helped to break stigma around women wearing trousers. CoCo Chanel and other designers contributed to this positive trend by producing garments like the two-piece suit for women, which emulated masculine corporate power.

Nowadays, with the exception perhaps of the high heel, women’s clothing is less in need of functional reform. Fashion is becoming increasingly unisex, and oriented towards the comfort and contentment of the wearer. A woman can even stride through a presidential campaign with relative ease, as evinced by Hillary’s much celebrated pantsuit.

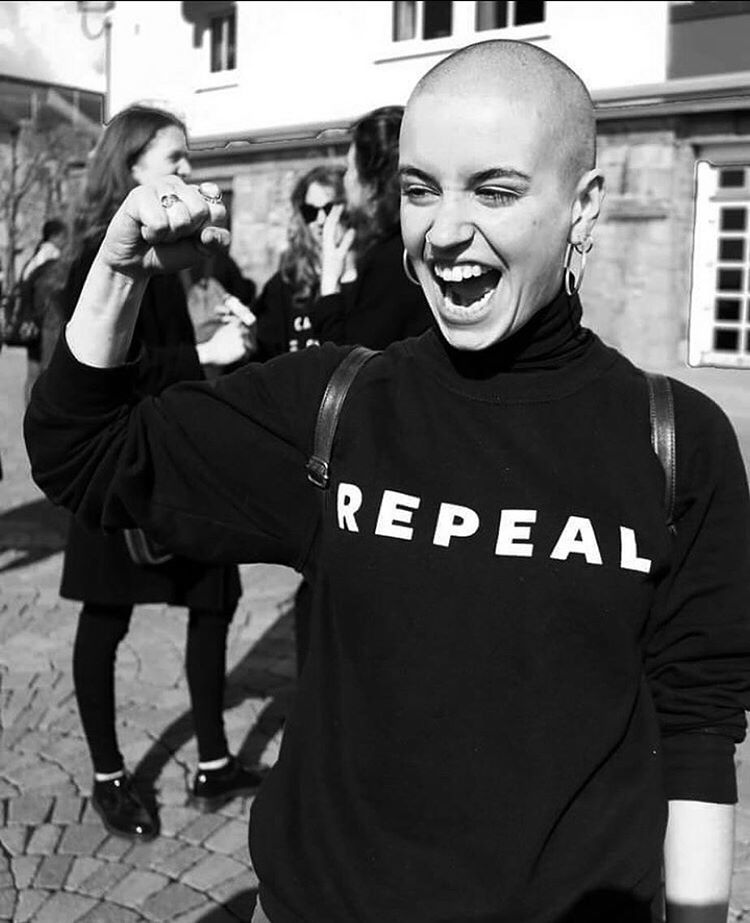

But feminism has not abandoned fashion, or vice versa. Women may have successfully subverted the patriarchal attempt to imprison their bodies with corsets and crinoline, but their bodies are still policed by society. In Ireland today, women are prohibited from accessing abortion services by the eighth amendment to the constitution. They have incorporated fashion into the battle to have this amendment repealed.

The Repeal Project was set up by Anna Cosgrave. She decided to design a REPEAL branded jumper in order to draw attention to the issue of abortion in Ireland – “outerwear to give a voice to a hidden problem”, as the tagline goes. This ties in with a trend of feminist symbolism and branded statements in fashion in recent years, exemplified by Dior’s “We Should All Be Feminists” T-shirt. In the post-pantsuit era, sartorial feminism is mainly about symbolism, statements and ideology, rather than fighting for functionality.

Fashion as a field is frequently belittled and dismissed as shallow (a criticism rooted in misogyny), and some commentators are quick to write off the jumpers as a ‘too-cool trend’.

Cosgrave’s jumpers struck a chord with the people of Ireland, becoming an overnight phenomenon. They spread like wildfire around the nation, were donned by celebrities, and are now ubiquitous at festivals, concerts, colleges and protests all over Ireland – anywhere that the youth congregate.

The popularity of the jumpers among young women has elicited condescension from many. Fashion as a field is frequently belittled and dismissed as shallow (a criticism rooted in misogyny), and some commentators are quick to write off the jumpers as a “too-cool trend“.

Some would say that these jumpers, and political fashion statements in general, are an example of “slacktivism“. The criticism is that people can wear them and thus fool themselves into believing they are fighting for change, without ever backing their politics up with action. This can engender apathy and a false sense of achievement that suffocates any motivation to make a real impact.

But these criticisms fall flat when you consider the very real impact the REPEAL jumpers are making on the ground in Ireland. Rather than detracting from other political actions like protests and lobbying, they are bolstering and fuelling them. The attendance at the annual March for Choice in Dublin skyrocketed from approximately 5,000 in 2014 to over 20,000 in 2016, and only last week, thousands congregated in Dublin for the Strike for Repeal protests – in both cases, the crowd was a sea of black and white REPEAL jumpers.

The jumpers are an ingenious mechanism of campaigning and proselytising. We are the meme generation, and we find strength and solidarity in the sharing of viral symbols and images. The REPEAL jumpers are capitalising on this effect, and galvanising the youth of Ireland in the fight for women’s rights. Oppressors always seek to convince you that you are alone – the jumpers cut through that fear, and remind women they are not. One person wears one, which inspires another with the confidence to wear one, and so on. The result is that more people are talking about abortion rights, more people are converted to the cause, and more people are attending protests.

On a practical level, there is no doubt the jumpers have energised the movement. But what is equally important is the rich, multifaceted symbolism of the jumpers.

For centuries, the Catholic church in Ireland, in partnership with the state, has cultivated silence around the issue of abortion. It is estimated 12 women a day travel to the UK to obtain abortions, but the Irish government attempts to sweep this reality under the rug. The church’s history is one of cover-ups, secrecy and disinformation. The jumpers symbolise the collectivisation of information – the sartorial equivalent of screaming from the rooftops. They are a categorical refusal of silence, symbolising the waning of the church’s power over women’s bodies. Wearing the jumpers, actually carrying the material around, draped and displayed on the body, is like a representation of a hidden burden all women have been carrying. It is an exorcism of a collective demon.

Their designer Anna Cosgrave, explains how she aimed “to give a voice to a hidden issue”, so that women who were “silently carrying around their personal experience with abortion could feel supported by strangers on the streets.” Crucially she wanted to “move the conversation offline, and humanise the issue.”

The jumpers possess a simple genius. Out of a crowd of people milling on Grafton Street, you suddenly glimpse one, and you remember – 12 women travel to the UK everyday to have an abortion. They force women’s pain into physical reality. Men don’t have to think about abortion because it doesn’t affect them. Women don’t have a choice. These jumpers take away everyone’s choice – in a positive way – they make everyone has to think about abortion. The jumpers prevent it being swept under the rug, denying the establishment the power of obfuscation. To Anna, the meaning can be summarised in one sentence. “You are not alone; together we rise.”

Throughout history, fashion has both impeded and empowered women. Today in Ireland, women are using a simple fashion statement to consolidate their power over their own bodies, continuing the legacy of the Victorian dress reformers all those years ago, who believed that women’s clothing should work for them, not against them.

Credits

Text Brian O’Flynn

Image via Instagram