The title of the exhibition Resting Our Eyes — currently on view at San Francisco’s ICA — “is a reference to what we’ve heard our grandmothers say for a long time: I’m not napping, I’m just resting my eyes,” says Autumn Breon, a curator and artist who studied aero- and astronautics. She conceived of the exhibition with Tahirah “T” Rasheed, a former lab assistant turned neon artist and co-owner of a sparkling cannabis beverage. The two met through Wide Awakes and For Freedoms: global collectives at the intersection of civic engagement and art (co-founded by artist Hank Willis Thomas, whose work is included in the show). The exhibition celebrates what rest “means from an anti-capitalist, anti-racist framework,” Autumn says.

The curatorial duo share an abolitionist practice, and the bedrock of their concept sources from ancestors and elders. “It’s kind of a meta approach: it’s almost like fractals. I think that’s a big part of our culture and our existence. We are remixes of those that came before us,” Autumn notes. To start, the two shared reference texts with each other, and one they kept returning to was the Combahee River Collective statement — a collective of queer, femme, Black writers and organisers who posited that if Black women were free, all oppressed peoples would be free, because intersecting systems of oppression would have been dismantled.

Another frequently-referenced thinker was Tricia Hersey, founder of the Nap Ministry (an idea underpinned by “sleep deprivation as a racial and social justice issue”) in addition to writing Rest is Resistance: A Manifesto. “For Black women specifically,” T says, “I think part of rest is refusal politics… No, I’m not going to do it this way. That’s also self-care — just saying no. For so long, we’ve been treated as and seen as the mules of the world: we’ve been doing for so long the work that has to get done that nobody else wants to do, which we get paid less for.” Autumn adds that, “combined with the toxicity of hustle culture, it’s literally killing us with those high cortisol levels.”

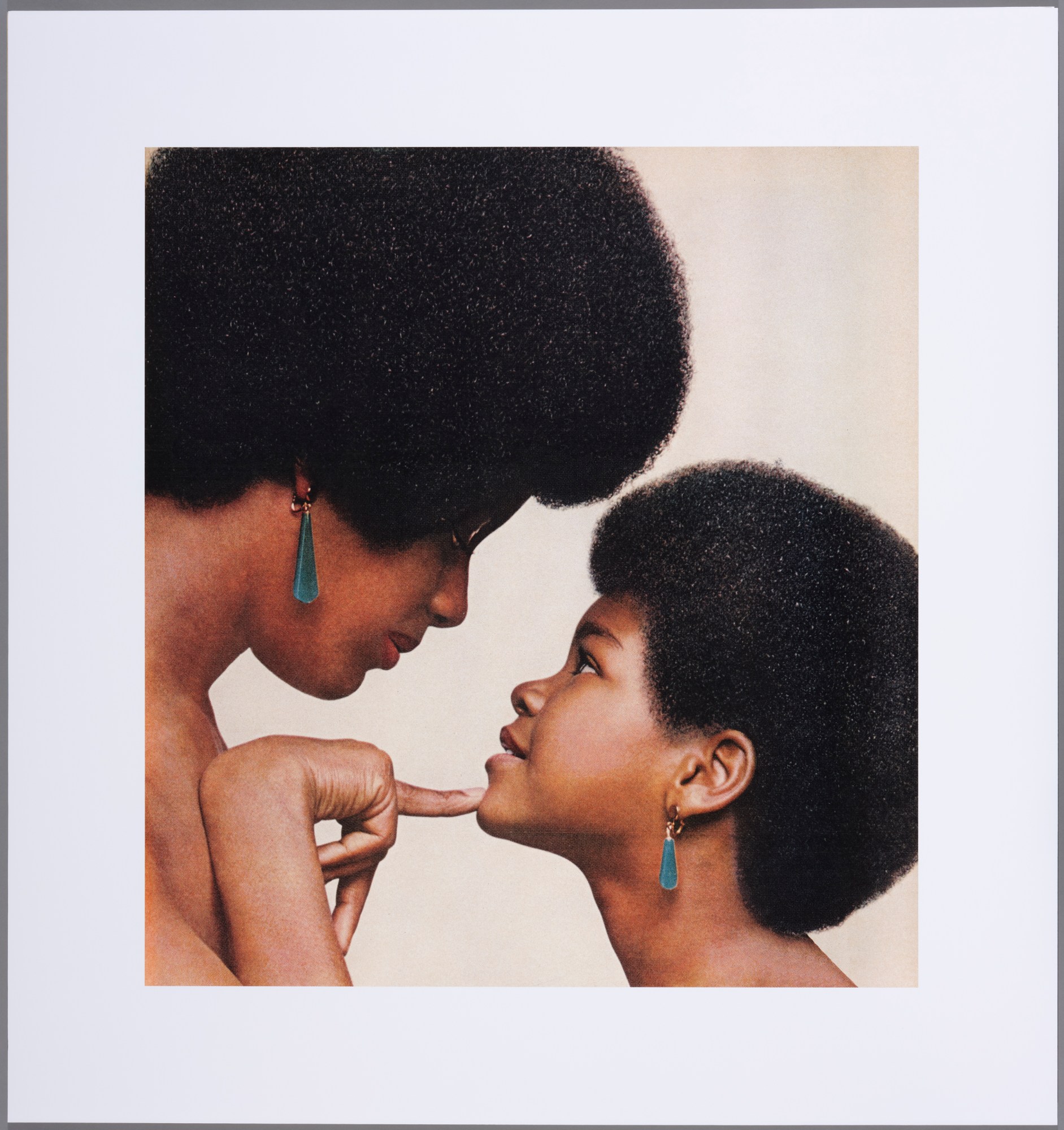

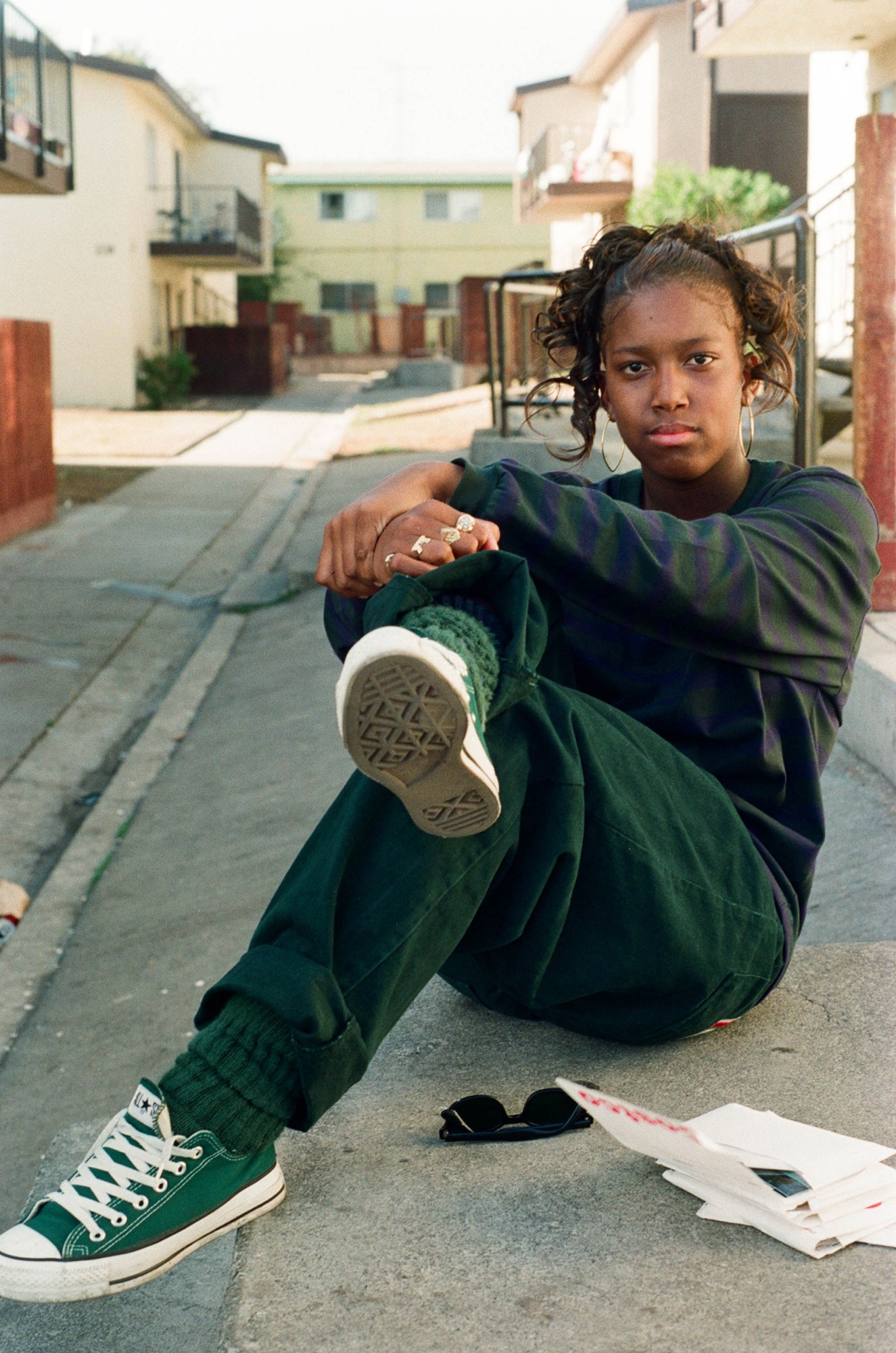

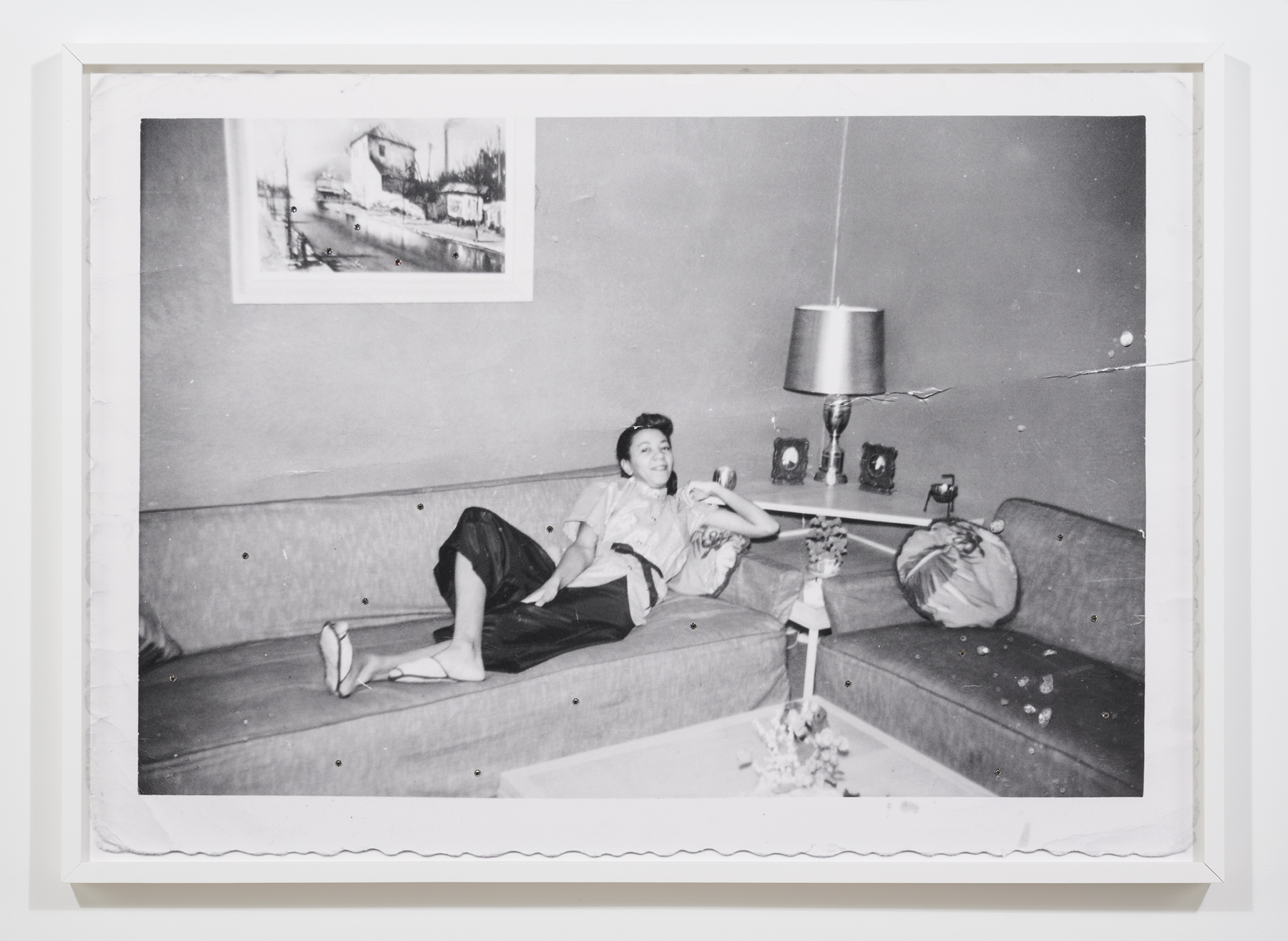

The exhibition spotlights Black women by way of 20 artists across generations and media. Alongside more emerging figures, blockbuster names include Carrie Mae Weems, Mickalene Thomas, Lorna Simpson, and Simone Leigh. Studio visits and negotiations with collectors allowed the curators to gather together artists who have created a visual vocabulary for the ideas they champion. It was key to both curators that the exhibition be held in an institution that welcomes visitors free of charge. The museum context itself practices what it preaches: presenting visitors with a calm and welcoming setting.

Rest and self-care often have a gendered emphasis, and not always beneficially: the themes are tied to industries that have profited off the narrative of release. Autumn acknowledges: “I do think that there has been a recent capitalisation on self-care. But self-care and rest isn’t just, like, using a jade roller before you go to sleep or overpaying for some yoga class. It’s about finding moments where productivity isn’t the goal — a moment where you are prioritising yourself. And sometimes that’s through a conversation, or taking a little bit longer to read a book. I don’t think that it has to be something performative or super expensive.”

That perspective shaped how Autumn and T thought about which works would help communicate a favourable — and valuable — approach to self-care. Alison Saar was on the list from the beginning. “I love how it occupies space,” Autumn enthuses of her piece “Set to Simmer,” composed of wood, ceiling tin, enamel paint, wire, a found table, a chair, and a skillet. As someone who creates neon pieces herself, T describes Ja’Tovia Gary’s 2020 work “Citational Ethics (Saidiya Hartman, 2017)” — featuring the words “care is the antidote to violence” — as “a must”. Of these layered and referential works, Autumn clarifies, “I don’t think of this as encouraging the audience to have to do labor, but instead encouraging meaningful engagement: to see more of Carrie Mae Weems’ work or to read [Black writer and academic] Saidiya Hartman if you have not already.”

The overall selection of works creates an emphasis on embodied experiences, but not all of them feature the figurative. Pieces estranged from the body include Knowledge Bennett’s geometric forms in black acrylic paint and diamond dust. “I felt like I was looking at the night sky and getting really lost in it,” Autumn notes of Knowledge’s work, “and I was thinking, what does it feel like when you’re resting your eyes? I just like when you look at something and your eyes get a chance to breathe for a minute… that’s one of those moments within the exhibition where you’re intentionally encouraged to linger a little bit longer.” Lava Thomas’s work “Clouds of Joy,” featuring a flurry of wall-mounted tambourines, evokes “Sundays and the Black church, and how that’s been a huge part of rest for our people,” Autumn continues. “Those tambourines were extremely nostalgic, and they take up space in a really beautiful way.” She recalls reading about how, in Santa Monica in the early 20th-century, the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church congregation would hear the Sunday service and then walk to the beach.

For T, Derrick Adams’ 2016 piece, “Floater No. 2”, had special resonance. “It is about leisure as a radical act of what is able to happen once you have that time and space to create,” she said. “When I’m sailing on my boat, that’s what it feels like… so much literal space is freed up in my mind… to start thinking about creative projects that I want to work on, or just to not really think about other problems because of how small I recognise myself to be once I’m in the ocean.”

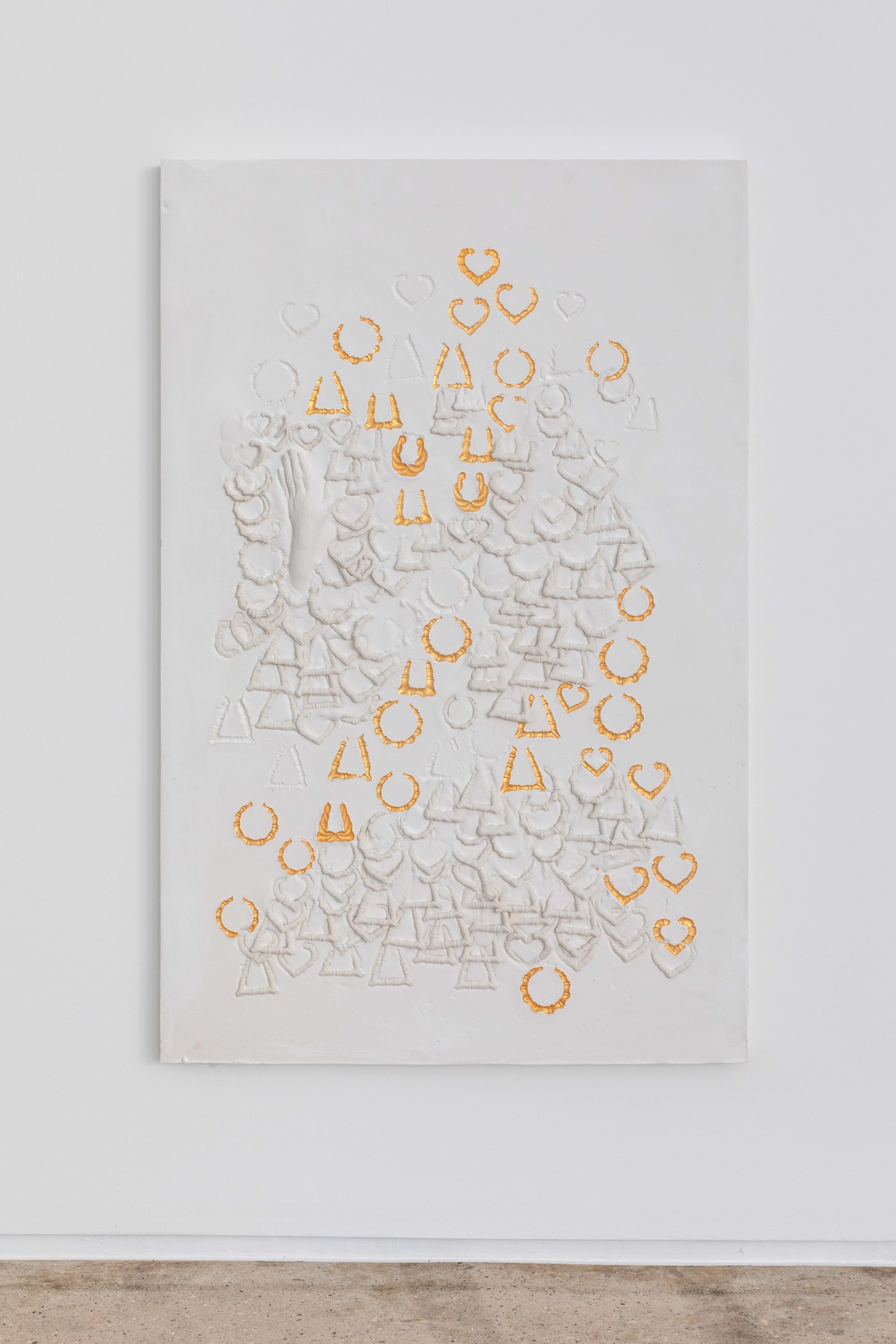

LaKela Brown’s 2021 “Composition with 35 Golden Doorknocker Impressions” — featuring an item available at the beauty supply store — spotlights an accessory Autumn considers to be “walking art that we saw every day”. She did a studio visit with LaKela in Brooklyn before the exhibition, and called T — wanting to share her enthusiasm for the work through “these epiphanies that I’ll have sometimes”. Autumn FaceTimed T, who was on the West coast and and three hours behind, half asleep. Fittingly to the theme, Autumn said, “Stay horizontal — stay rested” and did a studio tour on her laptop for T while she was still in bed.

‘Resting Our Eyes’ is on show at San Francisco’s ICA between January 21 – June 25. Further information and tickets are available here.

Credits

All work courtesy of the artists