Matthew Stone’s created some of the most instantly recognisable work in i-D’s history; his cover shot of Twigs for example, then a relatively unknown dancer, her gap toothed smile, poised wink, babyhair teased into spelling Love, ruffled collar, decorated with jewels and piercings. Inside the issue Matthew wrote of optimism as cultural rebellion. His work at that time was a magnificent mess of naked bodies, reaching towards the delicate poise of Renaissance formalism in composition and sculptural beauty, arms and legs and chests stretched out and suspended amongst each other. In an age of cynicism and irony, Matthew’s heartfelt genuineness felt revolutionary.

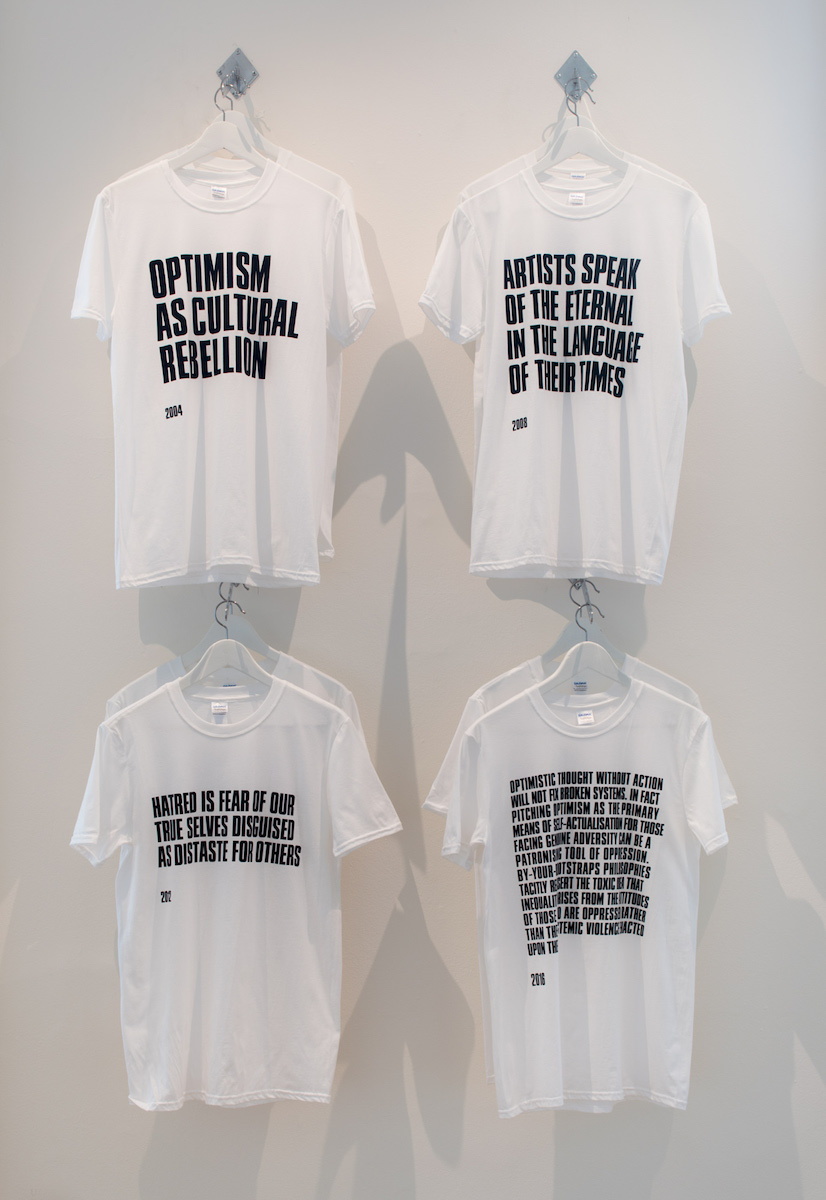

His new exhibition at Somerset House, Healing With Wounds, is part retrospective, part plotting out of his future. It charts his thought, first, with that optimism as cultural rebellion, and later, the realisation that optimistic thought without action will not fix broken systems. These statements, printed on t-shirts, map his progress as an artist.

Healing With Wounds revisits important works from across his career as well as exhibiting a series of new paintings. It takes in his early work with photography, as the leader of the !WOWOW! collective, creating work that slipped between fashion and art, and includes his recent work with painting, a series of beautiful abstractions, spins and swirls of colour and shape.

As an artist, his restless search for beauty has led to his work finding form in paradoxes, between figuration and abstraction and back again, a pursuit of optimism in the face of cynicism but a realisation that optimism can only get you so far. His new paintings, the centre piece of this exhibition, bring together those paradoxes, they marry the old and new in his work, bring the body back into his abstract paintings. We caught up with Matthew to talk over the exhibition, the past, present and future.

You called the exhibition Healing With Wounds, why?

I have spent the last three years or so recovering from chronic fatigue syndrome. The process of healing has presented a big learning curve. Given my levels of enthusiasm and energy, experiencing this was devastating. I slowly came to see my illness as a type of teacher. In the past I often talked about the nuances of emotional intelligence and the importance of embodiment of it. I think that naively I subconsciously assumed that because I could understand these ideas that I didn’t need to apply them. So I have had to humble myself and allow these ideas to sink into my body. I am no longer invincible. Experiencing periods where I have had a total inability to do certain basic things has taught me that a shift in attitude (or more specifically feeling optimistic) cannot fix everything. The title relates to the Jungian archetype of the wounded healer, which I understand to be the idea that the therapist is both driven and able to heal because of their own pain.

Pre-Brexit I had decided to call the show Healing With Wounds but it started to feel ‘too much’ somehow. I worried people might write it off as arty poetic logic not worth considering further. So I was going to call it just Healing. When I woke up and read the result of the referendum, I cried a bit and immediately changed the title back to Healing With Wounds. I knew that the popular political climate had shifted.

Can we talk about the new paintings? They are kind of a development of some of your more recent work. What lead you to this growth?

Practically speaking, these new works bridge the gap between the older group nude photography I have done and the abstract printed paintings I worked on between 2013-2015. Essentially I went largely on hiatus from the body and big abstract painted gesture filled its place. There was still a connection in the movement of the brushstrokes and a sense of fleshiness throughout, but mainly I needed some time to really think about the political implications of the ways in which I used other people’s bodies. I felt that the images I’d made in the past sometimes implied neutral utopias that ultimately didn’t reflect the complexities of real life. Being able to create and manipulate virtual figures, and to experiment with colour in these new works gave me space to create more ambiguity. Photographs of nude bodies almost immediately illicit assumptions, mainly of gender and ethnicity; and in placing them together you have to make a series of complex decisions about how power and hierarchy might end up being implied. I have a strong desire to create positive images that promote social harmony, but I have also come to understand the extent to which overly positivistic narratives can be patronising and become in themselves tools of oppression. These works come out of that thinking. They are an attempt to recognise both the difficulties of and inherent potential and continuing need for mutual and interdependent types of societal healing.

What is the process behind them?

I start with physical painting, making individual brushstrokes and then photographing them. From there I work with about seven different pieces of software to model, sculpt and pose the figures and then selectively apply the strokes to their surface. I use a virtual camera to frame the figures and then render an enormous file, which is then finally digitally printed onto the raw linen.

The other new works are the sculptural pieces, with digital screens. What can you tell us about them?

They are sculptural installations of video and text based work, formed of custom coloured MDF plinths with tilted perspex boxes on top. Inside the cases, I have installed stripped back LCD screens that have archival video works on them. One of the cases also includes copies of i-D and System magazines, both issues of which visibly contain texts I have written on optimism, kindness and love. In the past I have been rather promiscuous in terms of the mediums and cultural contexts that I have placed my work and ideas within. This cross-cultural approach that has breached fashion, art and music has always been part of a web of interconnected thought and activity for me. I am aware that some have found it hard to comfortably frame me and my work as a result. By physically containing diverse constellations of my work and ideas I can create little ecosystems that claim some ownership of the creative energy I have expended outside of my own, more conventional autonomous art practice. The question of whether these activities constitute art is less important to me now. I just wanted to explain that my intention in these arenas has always been to use diverse cultural contexts as artistic medium in real time.

The rest of the exhibition is almost a mini retrospective, featuring pieces from throughout your career. What made you want to revisit them?

I didn’t want to initially! I was worried it would seem like I was trying to have a ‘mini-retrospective’ ha! But by including a few bits from the different bodies of work I have made seemed like an honest and transparent way to explain how I got to the new works. Also quite a few of the works had never been shown in London.

How did you go about selecting which works to put in?

I just avoided including all of the works that I find deeply embarrassing now and was left with the few works that I ended up including!

Which is your favourite retrospective piece in the exhibition?

I like the t-shirt installation that includes some of the statements or slogans I wrote over the last 12 years. Although the t-shirts were made in the last few weeks, the short texts represent some of the key ideas I have had over time and aim to chart the development of my thinking. The first one (dated 2004) says “Optimism as Cultural Rebellion” and the last one (from 2016) says, “Optimistic thought without action will not fix broken systems. In fact pitching optimism as the primary means of self-actualisation for those facing genuine adversity can be a patronising tool of oppression. By-your-bootstraps philosophies tacitly reassert the toxic idea that inequality arises from the attitudes of those who are oppressed rather than the systemic violence enacted upon them.”

In slight contrast to what I just said about my older work, I enjoy that fact that the two statements seem at odds with each other. Rather than getting embarrassed, it feels good to show that friction and shift in my thinking. I don’t need to hide the statements I have made in the past.

The exhibition is part of the larger Utopia project at Somerset House. What does Utopia mean to you?

I would say that there are dangers in the often essentialist nature of utopian thinking. Vast horrors have been committed in the name of varying social utopias. The application of one person’s dream of freedom and happiness is highly unlikely to create space for another’s lived reality. And whilst I think that sensitivity to these complexities is wholly essential, the complete rejection of idealism can be a form of intellectual narcissism that represents a privileged decadence in the face of a very troubled world. Those who seek power over tenderness don’t seem to feel the need to face these difficult realities when it comes their shaping of the future. So therefore conscious opponents still need to exist. The Greek root of the word utopia literally means ‘nowhere’, so by definition true utopias cannot ever really exist. So I think that falling short of far reaching visions is more favourable than not working towards them at all.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Portrait by Ronan Mckenzie