This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Icons and Idols Issue, no. 359, Spring 2020. Order your copy here.

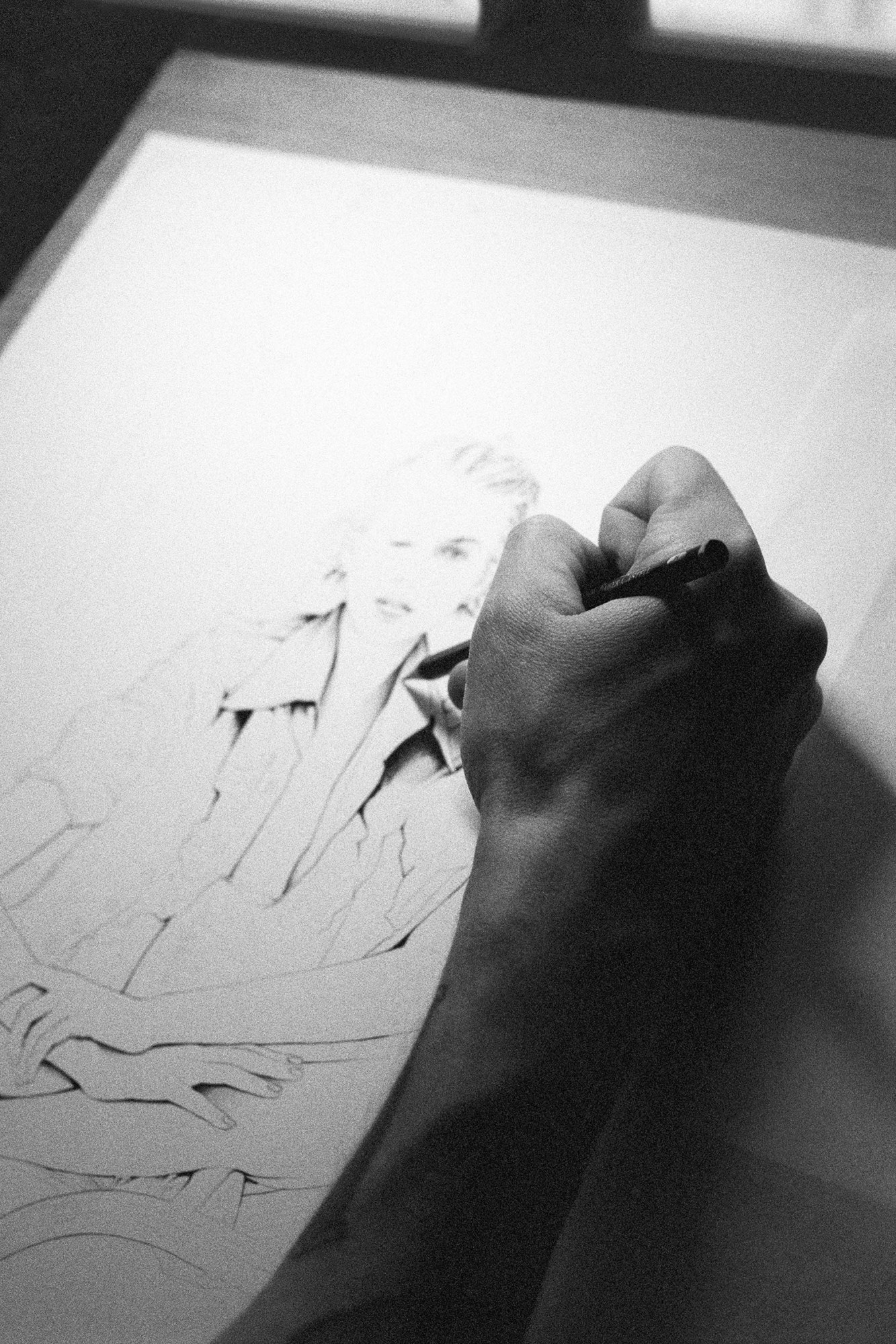

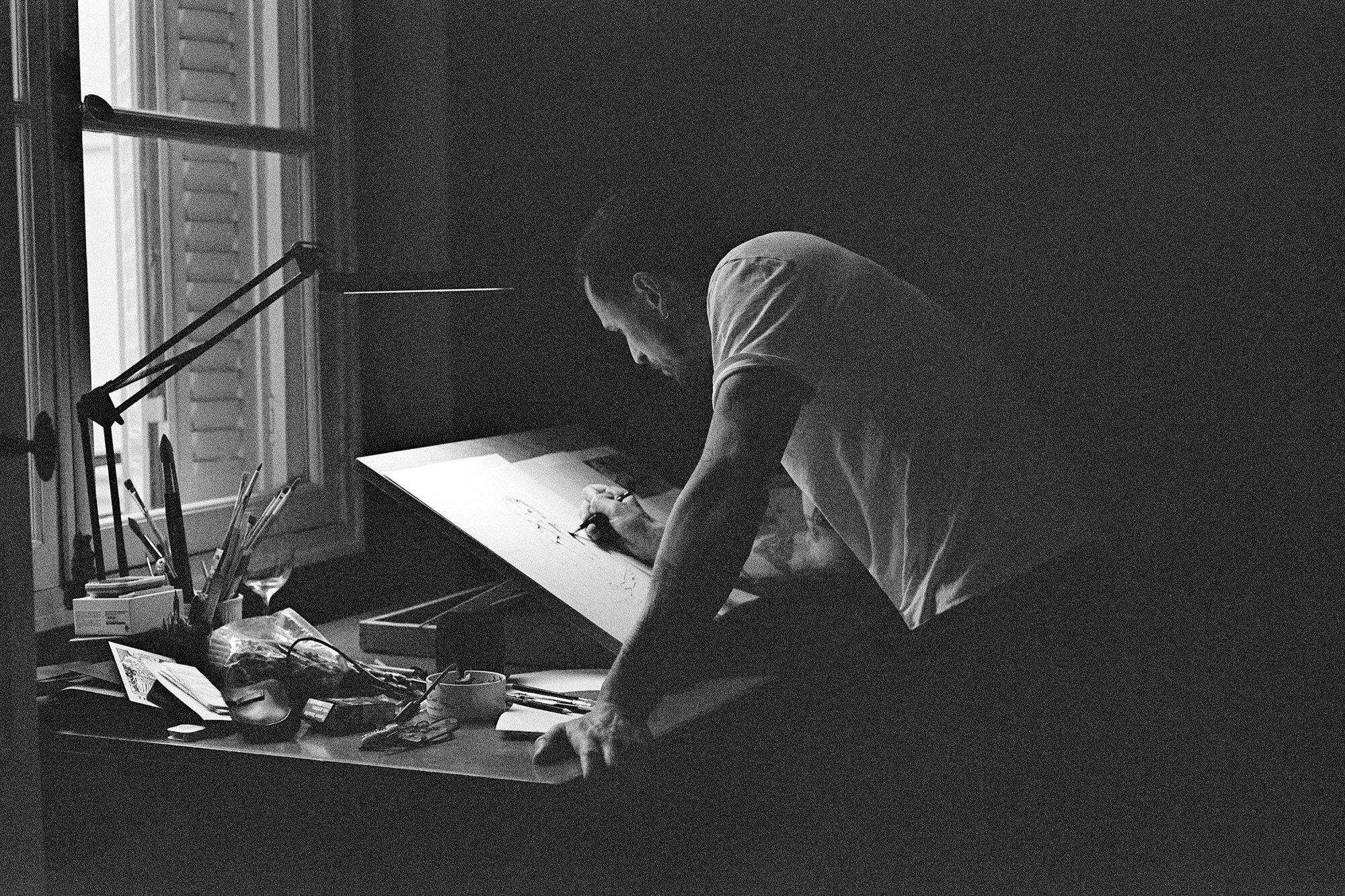

Renewed interest in the art of illustration is an interesting phenomenon to observe in today’s digital climate, where both the production and consumption of photographic imagery is so readily accessible. It’s a backlash, maybe? Like portrait painting, it’s the antithesis of the instant, requiring time and effort to build an image from scratch. The illustrated line is an elegant medium: it flirts with negative space and demands scrutiny. Depending on an illustrator’s style and scale, a work may reveal itself more readily at a distance or be better appreciated up close. Likewise, drawing retains a foothold in both the analogue and digital worlds, with technology lending the art form new means of execution and exhibition (Look! It’s moving!). The Spanish-born artist Ricardo Fumanal is one illustrator who has mastered this remix, walking the tightrope between traditional hand drawn sketches and their digital manipulation and embellishment.

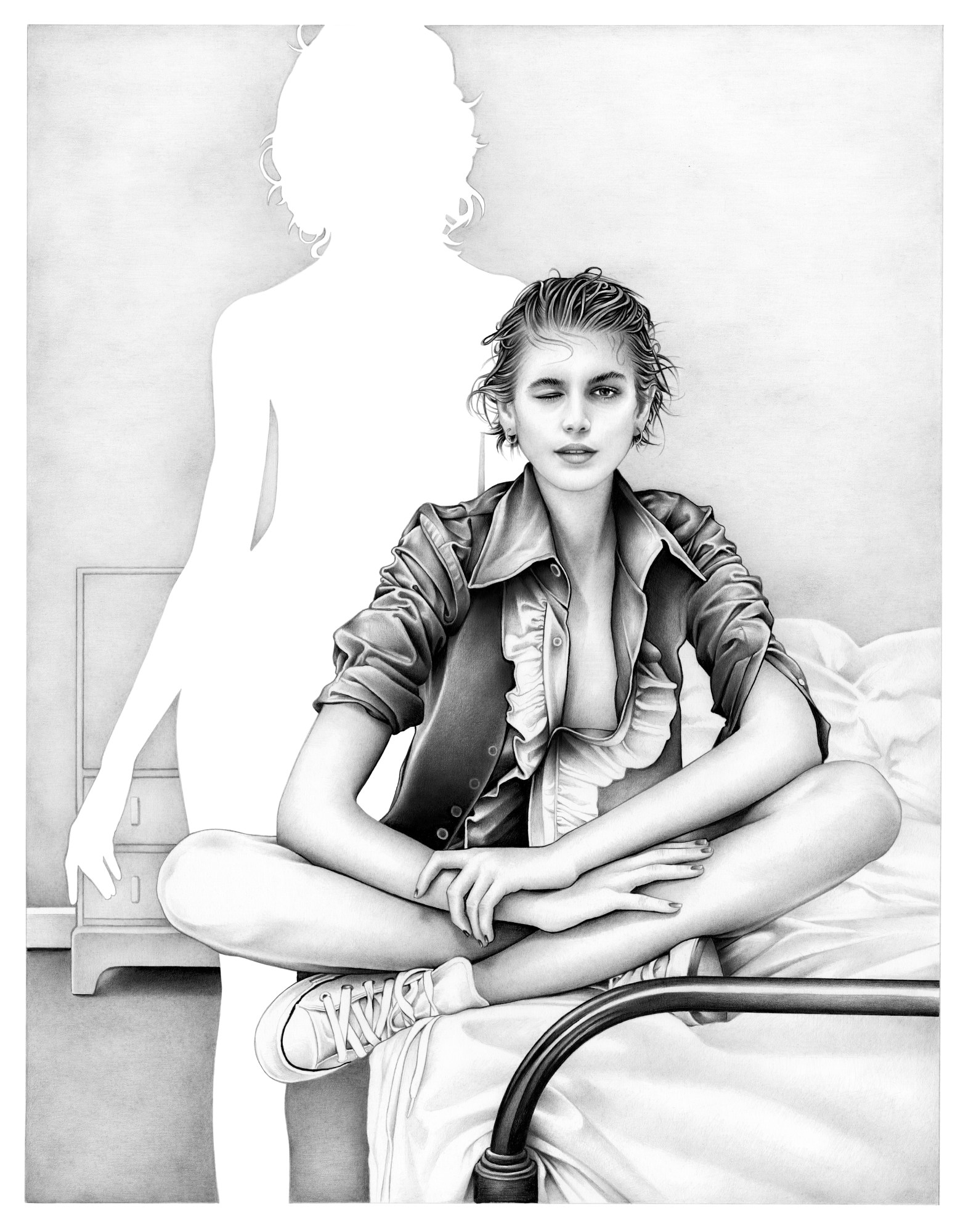

His unapologetically pop-inflected creations are subversive in multiple ways, from their comment on classical shading and airbrushing techniques to absurd plays on proportions and a healthy dose of sex and tongue-in-cheek humour. Recently, after years of developing both his personal portfolio as well as brand and editorial commissions in fashion, Ricardo has applied his distinct aesthetic to a line of bold T-shirts under the name Sticky Ricky. Each features his glossy, larger-than-life illustrations and have been seen on Bella Hadid, Mica Argañaraz, and Kaia Gerber. For this issue of i-D, he’s transformed Willy Vanderperre’s photograph of a Converse-clad Kaia into a softly shaded monochrome drawing.

We live in a world where technology has revolutionised many traditional art forms. Can you talk us through the split between digital and analogue drawing in your work?

My work is a dance between analogue drawing and digital design. It’s informed by a play between the two. As a child I would draw obsessively, which eventually spurred my interest in studying art. Focusing on hand-drawing and painting throughout my college years, I only entered the digital sphere later, but my style is the amalgamation of hand-drawing and digital collage. For me, they are linked intrinsically, and my work cannot exist with only one and not the other.

How did you approach Willy Vanderperre’s photograph of Kaia Gerber? What is the new rapport you have created behind Kaia as the protagonist and the new female ‘negative space’ you have created behind her? Is there an attempt to create a certain tension here, sexual or otherwise?

In my personal work, I get to be the creator of both the subject matter and environment as well as the dynamic and the tension. Working with Willy’s image of Kaia, I saw myself no longer as the creator but rather the collaborator, keen to respect the subject matter and environment so beautifully established while finding a way to disrupt the image with my imagined new dynamic and tension. I would imagine some people could possibly see it as a new woman who is invading Kaia’s space, while others might see it as an alter-ego or maybe a projection of Kaia? To be honest, I prefer to leave it open to the viewer’s interpretation.

In your pornographic series of drawings, it’s interesting to see how your work removes much of the taboo from a sexual image through three steps – the first, making it black and white. The second, transforming a photograph into a drawing. And the third, removing a central protagonist so that merely the idea of their genitalia and their physicality remains. What is your thought process behind this? How does it relate to your other work?

I consider them somewhat distinct from my other work. The series is probably my most personal, it’s quite representative of my sexual and emotional journey. While sex has always played a significant role in my work, this new series is intended as a study of the nature of desire: pornographic sex acts that feel intimate and sensual and obscene imagery rendered in delicate, almost poetic line and shade.

What does Sticky Ricky mean exactly, is he a character?

Can you explain the humorous side of these works and how you integrate human, vegetable, and other elements to create these new cartoon expressions? Sticky Ricky isn’t a character – although he might be evolving into my other personality! The idea was to develop something distinct from my personal and commercial work. The illustrations created as Sticky Ricky were planned, from the beginning, to be printed on clothing. For the first series, I wanted to do something quite direct, colourful and pop and very tongue-in-cheek. The end results might be NSFW but they are quite fun.

Why do you think that the art of illustration has lived on through the revolution of photography, digital photography, smartphones and all the other means that we have to record exacting images of people, places, moments?

There’s a directness and physicalness to it, an extension of myself transferred to page, that cannot be achieved by computer. I think that is why illustration is such an enduring medium.

You have mentioned using source imagery in your work, predominantly from the internet. Do you also rely on books and museums, more analogue means of research?

I’m a huge fan of the speed and immediacy of the internet, and the infinite resources and visuals. It’s great to be able to switch from looking at vintage pornography to ordering food at the click of a button. I’m less keen on museums or library research, but I do look to old magazines or books for inspiration.

By featuring gay erotica in your work, do you seek to place it within a certain community?

I wouldn’t say that my primary goal has ever been to make gay art. But I’ve always been drawn to gay erotica and the male body, that’s why they are recurring themes in my illustrations. My work is definitely an exploration of my own sexuality, but it is also intended to be a study of sensuality, connection and love.

Do you remember the first drawing you ever did? What was it?

I actually recently found a sketchbook from my childhood and it was filled with drawings of chili peppers, aubergines and extremely high heels. Quite telling!

When you are composing new works, where does reality stop and your imagination begin? How do you decide to personify a gherkin, or make eyes out of nipples?

My work is a cycle of research and composition, the initial imagery forming the first idea. But as I start manipulating an image, layering new elements, reality bends and my imagination powers the cycle of adding, amending, subtracting and distorting that eventually leads to a final composition. There’s no moment where reality ends and imagination begins, rather a series of impulses and pauses that lead me on a journey.

Credits

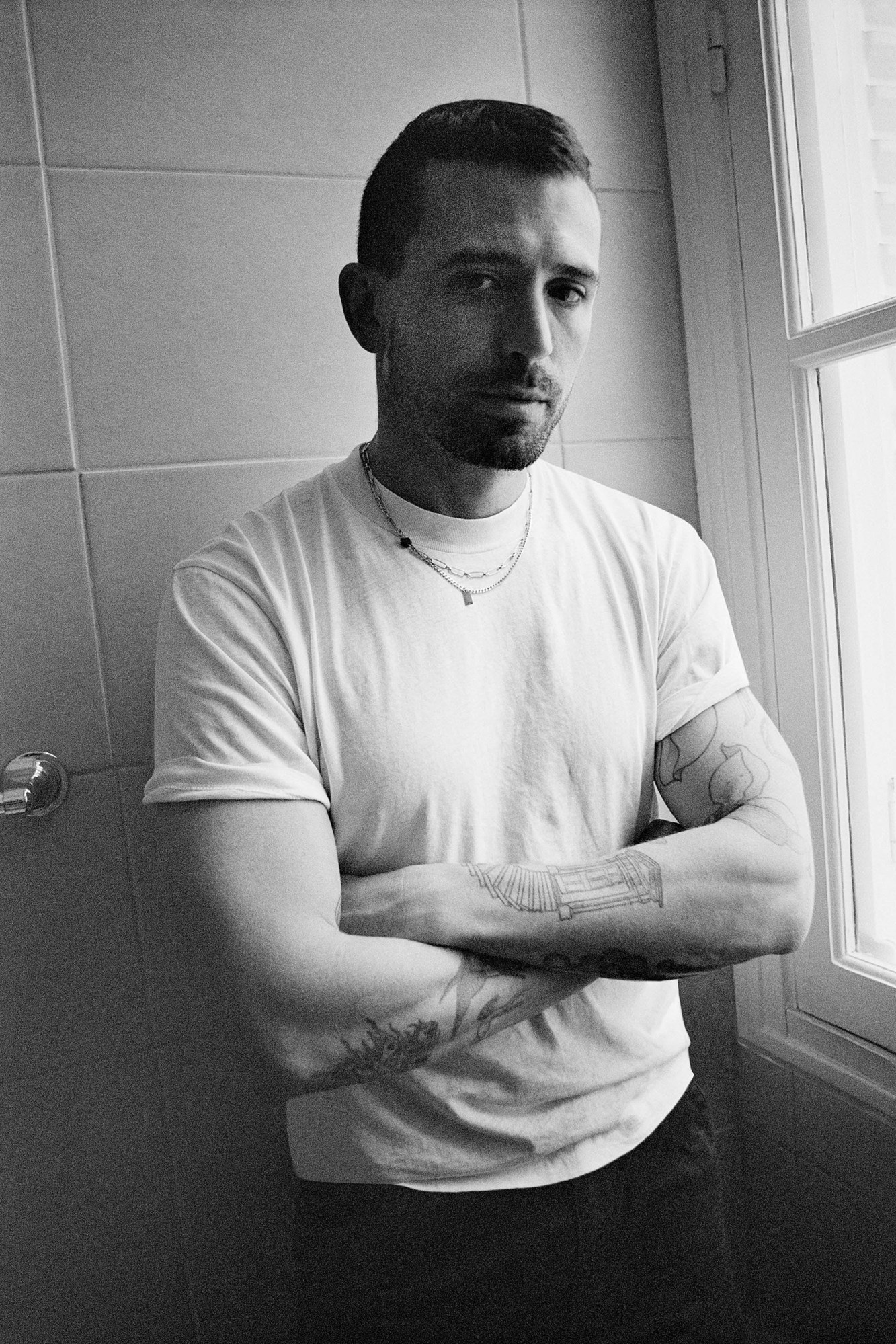

photography Ian Kenneth Bird