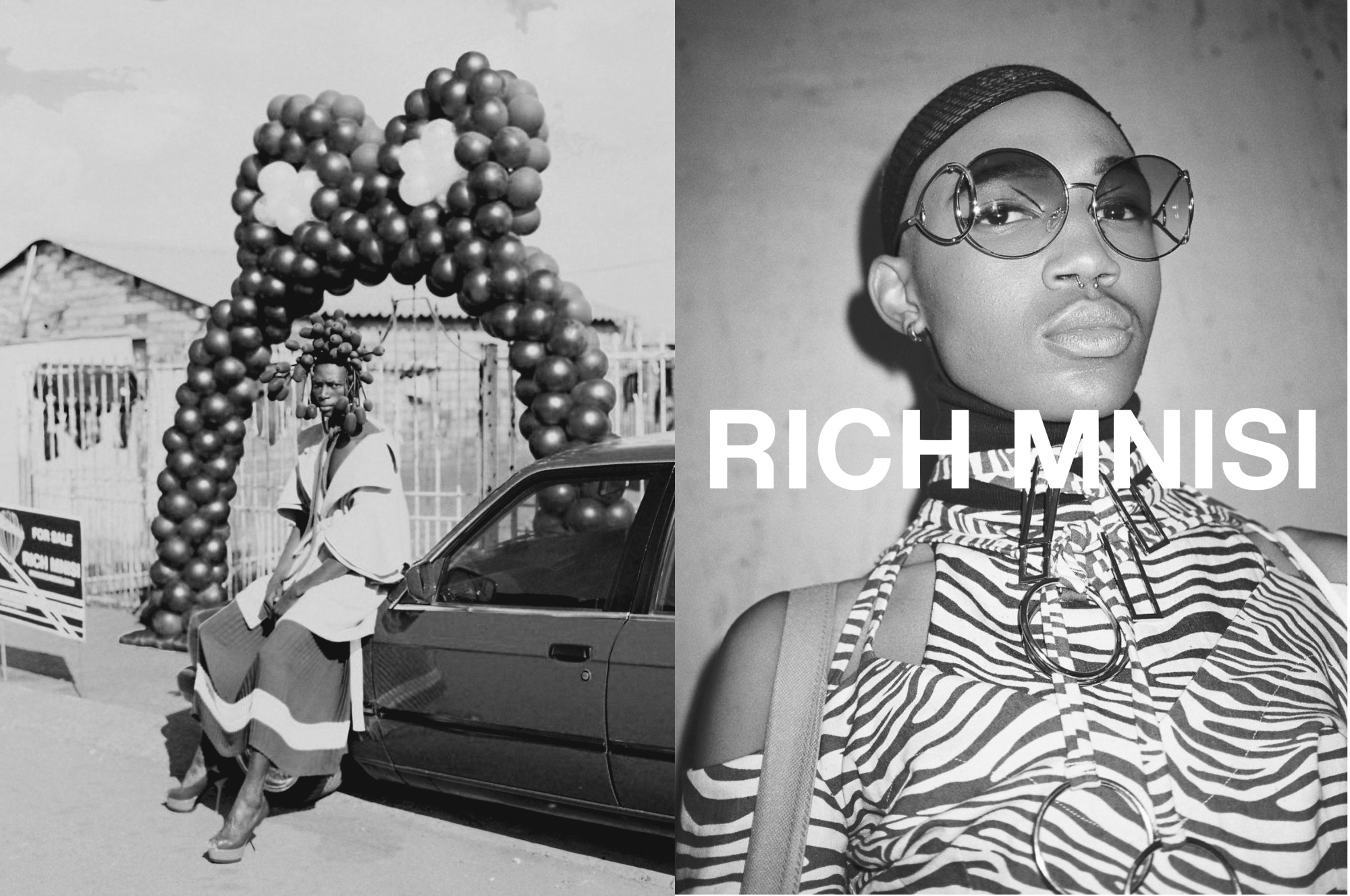

“I’ve been stalking you on Instagram and I was honestly blown away by the art direction,” Mykki Blanco confesses to Rich Mnisi in Episode Two of Out of This World. “The clothes are beautiful but it’s the context in which you place the models that fascinates me.” His colour-filled, joy-jammed feed is an invitation to explore his whimsical take on his Johannesburg township reality as he makes sense of his race, sexuality and identity. From the moment LISOF graduate and African Fashion International Young Designer of the Year winner launched his gender-fluid eponymous label in 2014, Mnisi has spent the last three years probing perceptions, challenging collective consciousness and igniting imaginations. As he shares his Ricardo Simal-shot lookbook and campaign, Rich invites us deeper into his world.

What first drew you to fashion design?

My family are style conscious. Growing up, my mother, sister and grandmother all played with proportion, colour and pattern. They were very aware of how they wanted to present themselves. Particularly my sister, she’s 17 years older than me — old enough to be my mother — she’s a total fashion killer. She was into crop tops and bell bottom jeans, she’d dye them, cut them up and do all these wild things.

So you grew up around a DIY-culture of fashion?

Yeah definitely, especially with my sister. It was all about crafting things and reinterpreting things.

When did you see fashion design as a vocation?

When I was in grade twelve, my last year of high school. There was career day and the fashion college came to my school and talked about it. At that moment, I dropped everything that I wanted to do. My mother was a teacher and she wanted me to study law but I convinced her with this long letter — it was four pages of emotional blackmail. I told her that I’d rather regret doing fashion and failing than blaming her for taking a path I didn’t believe in.

What do your family think now?

My family are so supportive, they all contribute and offer suggestions. My mother sews buttons and everything, she’s deeply involved in the business.

Were you clear you wanted to start your label after graduating from LISOF?

I initially thought I was going to get a job in the design industry and then go corporate. But then I entered a competition and was crowned African Fashion International Young Designer of the Year. I was trapped after this initial success — I couldn’t go back and get a 9-5 job. I had to commit to this, do my research, find the manufacturers and do it right.

Three years on, how would you describe the Rich Mnisi label?

It offers a fresh perspective on what South African design is. It explores the aftermath of everything we went through as a country — it looks back at our history, our heritage and sees where we are today. Ultimately, it’s a hybrid of my culture. Colonisation, apartheid, the introduction of western elements, all of these things come together to create something new.

The nature of Mykki’s film looks at the LGBTQ communities in South Africa and your own work touches on this too. In your first campaign you cast Luke van der Burg, a transgender model and activist who you continue to work with today. How conscious are you of the need to use your platform to inspire positive change?

For me, I’ve never spoken about my sexuality or felt the need to. Even when I came out to my mother, it wasn’t a true coming out, I just introduced her to a boy. I’m not the most vocal person so I deal with it through other means, mainly my brand. When Mykki was here, that was the first time I ever uttered the words, “I am gay.” Everyone knows but I address it through my work. Even then, there’s no caption because people should just take it and accept it. In South Africa we’re very privileged and everyone’s starting to have conversations about LGBT communities. But when you go higher in Africa it’s still frowned upon, it’s dangerous to admit that you’re even slightly attracted to the same sex.

Your work continues the dialogue.

And that’s why it’s so important to me to have it in my visual language, so it’s something that you see and understand and that will stay in your mind. For me, words can be misinterpreted, people can forget things that you say but an image lasts longer in your head. That’s why it’s important for me to just plug these images. If tomorrow they see someone just being who they are, it’s not an unfamiliar concept.

How has your understanding of black queer masculinity shifted since growing up?

I’ve always known. Of course, I had those moments of ‘I have to fight this,’ because I grew up in a Christian home. And every night I used to pray against being gay. I’d be like ‘God, please heal me of this evil, of this demon that’s inside of me.’ And then you grow up and start having a different relationship with your faith… People deal with things in many ways and I know that I can play my role just by my brand existing. Touching on those topics is important as the more we discuss, the more it becomes normalised.

It challenges long-held beliefs and encourages people to question their own perceptions and prejudices. But of course, there are people who just absolutely don’t see it. I was held at gunpoint twice, just because I was gay. I stopped using public transport because of it. Since then, it’s Uber. I can’t even afford it but my life is more valuable. Either I stop dressing the way I want to dress or find other ways of transport.

Even in Johannesburg today?

Yes. The last time was in 2012 but I think the law adds this misleading haze over the reality — the law might declare gay marriage is legal but there will be people you interact with every single day that ignore progress. It’s not as liberal as you want it to be. But I guess one thing at a time.

Another small step is the Ricardo Simal-shot Xingelengele 17 campaign. Could you talk us through it?

It was shot in the Soweto township, around my grandmother’s place. I’ve actually shot three or four campaigns there. It’s where I grew up and what I grew up seeing. But I explore it from a child’s eye. I used to live in Kempton Park — the opposite side to Soweto — but every single weekend we’d visit my grandmother and we moved there ourselves in 2009.

There’s a whimsical lens placed over the everyday reality of the township.

It was approached with enthusiasm and that’s how I want to present it, with a child’s eye. That’s why this campaign is really child-like, with the balloons. So that’s really the core, presenting the clothes in that environment. Those clothes lived in that space but now they’re being presented in a different way. But presenting it from a small business point of view — we have a real estate agent, a guy selling fruits and vegetables… just all these things I grew up seeing.

How did you cast the campaign?

They’re friends and family. I’ve always worked with Luke, my niece took part in it too. For

Mykki — I suggested to the i-D team that we should shoot him so it’s not just him standing right there. It was cool to have him. He epitomises those ideals.

There’s a real sense of family around the brand. How did you all meet?

I met Luke at college but it’s a mix of finds, from agencies like French model Yannick Konan to chance meetings in social spaces and my family too, my niece is involved. Then one guy, Nkuley Masemola — the guy wearing the zebra print dress — DMd me and was like “Rich, please, anything.” Then I connected with him with i-D and we learnt his incredible story as well (in Episode Three of Out of This World).

Finally, if readers take one thing away from this campaign what would you want it to be and why?

It’s a collection of beautiful images, shot in spaces that any South African can relate to but presented in a childlike way. It references a five-year-old’s party more than anything else. It’s fun, celebratory, happy. Why? As much joy as the township gave me, there are a lot of problems as well and I wanted to shift the negative narrative. Often, shoots focus on the negative side and then slot in this beautiful model. And it’s like, what are you trying to do, what are you trying to say, what are you going to give back to the families? For my campaigns, it’s about respecting this colourful world, showing the positive, sharing the excitement and the beauty.

Read: What is life like for a young, queer artist in South Africa?