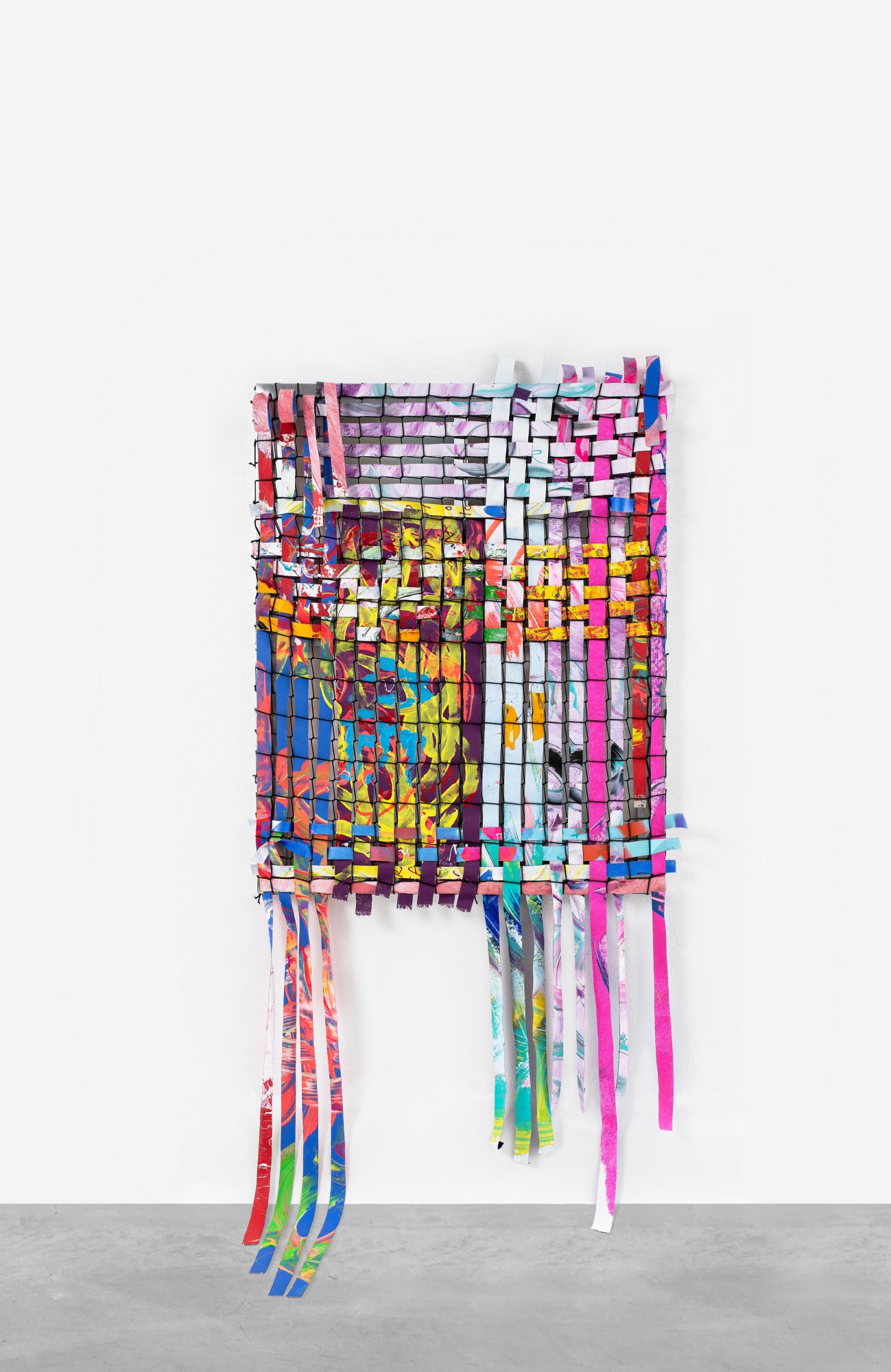

Ohio-born, Berlin-based Richard Kennedy works across performance, painting, and video to examine and celebrate the queer Black experience. Their solo exhibition Libretto Accidentale — recently on view at Peres Projects in Milan — featured textured abstractions of acrylic paint on linen, shredded-and-rethreaded paintings akin to remixed tapestries (all with excellent titles, like “Tameeka Had Gel’s Baby Hairs” and “Micro Braid Baddie”) and a video triptych.

During the opening, Richard and two close collaborators, Kyle Kidd and RaShonda Reeves, also introduced a contemporary composition into the mix. “Zeferina” drew from an ancestral narrative inspired by the eponymous Zeferina: an overlooked historical figure who led the Hausa Revolts in the early 19th century. This heritage figure informed the present-day polyphonic production; Richard drew from the classical music canon and reinvented it through African-American ideological rupture, emphasising Black resistance and liberation. The piece will be elaborated upon at LAB, The Industry’s performance platform in Los Angeles that supports experiments in opera.

Richard’s previous performances have been presented in New York at the MoMA and MoMA PS1, having come up through smaller arty-weirdo spaces. Their work was recently part of group exhibitions Futurismo at Mendes Wood DM in Sao Paulo and Ubuntu: A Lucid Dream at Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

Here, Richard speaks about scrappiness, show tunes and coming up in the New York queer scene.

Tell me about your journey as an artist.

I always felt like I wanted to be a renaissance person. I was obsessed with collaging, always cutting stuff out of magazines. When I went to elementary school, I was really into music classes. In the first grade, at Christmas time, my music teacher played The Nutcracker, and I was [dancing to] that in my living room.

I went to this pretty posh local dancing school, and everybody had parents who were doctors or lawyers or dentists. My parents are very hardworking people. [My job at] McDonald’s paid for me to go to ballet school. I was, like, 14 years old working to get some extra leg warmers. But I started to win competitions, and I ended up going to college for dance. I dropped out and, between the time I was 19 and 23, I was nationally touring in Fosse, West Side Story, Wicked… then I got injured. I moved to New York City and just went through scenes, met a generation of artists like the House of Ladosha, The Spectrum, Bearcat, Juliana Huxtable: all these really prolific people. I was in the band Ssion. I was in a show at MoMA PS1, which was like this big moment in queer culture: Sky Ferreira was in it, Mykki Blanco, Casey Spooner, all these people who grew to be these big stars. I didn’t know anyone — and I suddenly was in the middle.

I went to Bard to get my MFA, then I moved to Berlin and started making operas. Opera was kind of my window to the world because there was an opera house in my town. I grew up in this really crazy conservative town in Ohio called Middletown.

When I moved to Berlin, I really expanded my art practice, painting and making video works and doing sculpture — really making art new again for myself. I was just kind of blindly moving through the art world before.

You have more of a conservatory-style background, which encourages performers to excel at their craft but not reinvent it. Yet you mixed with art scene kids, who love nothing more than to willfully mess shit up. Can you talk more about that hybrid: classical references and deconstructed codes?

I think the separation is intentional: they don’t teach performers how to be imaginative, and they don’t teach art school kids how to be virtuosic. Just being a Black queer poor kid doing ballet and opera, I have always been disrupting things.

I think that the performance and video work from the show is really dealing with [the question]: Why do we build these things to tear them down? In Europe, tradition is really complicated. How can I use opera as a form that isn’t super authoritarian? It has been used as a container for so many problematic ideas, from Wagner to these really weird Orientalist operas where they’re still doing yellowface and calling it ‘tradition.’ Opera is the final gate, culturally. I can simply exist: I’m here. I’m just gonna take up space.

I don’t have a strong understanding of opera, but I started thinking about it in a new way specifically tied to your show. Disruption is also about how you push audiences to be curious about something that they weren’t before.

Yeah, I think my practice has been developing that. It’s this idea of mixing, putting the vernacular into an operatic space, making the connections.

The first opera that I worked on was called Black Rage, about the African American queer experience, where people deny your humanity, deny your reality when you’re trying to come through. We did it at Signal in Brooklyn. There were like 250 people, and they went crazy for it. I would do parties and shows back in the day with Yves Tumor at these Puerto Rican biker bars. There would only be a few people, but the shows would be insane: Psycho Egyptian, House of Ladosha, Abdu Ali, Quay Dash, Cakes da Killa, all these crazy queer pioneers of this era. With [my collaborators] Kyle [Kidd] and RaShonda [Reeves], we just have been consistently working together for about four years. It’s just like this major vessel to find your tribe, and be able to grow with them.

During your performance at Peres Projects, you announced: “this is very casual… you can be on your phones.” I’d never heard that sentence at a performance: normally, you’re expected to be super attentive and on your best behaviour. This too felt like a disruption, as a directive of how you absorb art, of how you receive something.

I want to always acknowledge what’s happening in the room. At the beginning of the opera, there’s always these announcements: Please turn off your phones. And I’m like, No, keep your phone on, girl. Take a video like you’re gonna do anyway — don’t sneak! If you want to send a text message, I don’t need that much attention.

Can you talk a bit more about Zeferina, which you performed an excerpt of?

This project started last summer. I got the idea for Zeferina from the book Black Marxism. It was like, ‘Oh, my God, this is like the perfect thing to do with Kyle and RaShonda’: I just want to always acknowledge them and let the world know about how integral they are, that this is a community. They fill me with knowledge.

Zeferina will have a workshop premiere, so it’ll be low stakes. I refuse to be pressured by an institution to define the role of this Black woman — who led a slave revolt, and was leading these Maroon communities [descendants of Africans in the Americas who formed settlements away from slavery] — so the work can never really be completed. Her name exists, but her story and her tale, these things don’t.

Is the visual art here an independent thread, relative to the performance, or does it complement the performance?

I’m starting to see that it is all connected. There is no separation to me, because when I’m in the studio, and I have a little ballet area, I have a painting area, I have a music area, I’ve got a library… And if I’m really in a vibe, I just move from space to space to space to space. I’m not reinventing the wheel; I’m seeing the wheel is missing some spokes.

The exhibition title, Libretto Accidentale acknowledges happenstance in the artistic process. It’s nice to highlight that, especially since “intention” is almost always what is brought to the fore when artists talk about their work.

I hate being in stiff, stuffy environments where everybody’s just so posh and just wants to prove who’s the smartest person. I’m really just trying to remain present and shift and be more like water. I’m a fire sign, and the fire just spreads and destroys. I’m trying to be a little bit more liquid — maybe put some of this fire out.

Credits

All artwork by Richard Kennedy, courtesy of Peres Projects