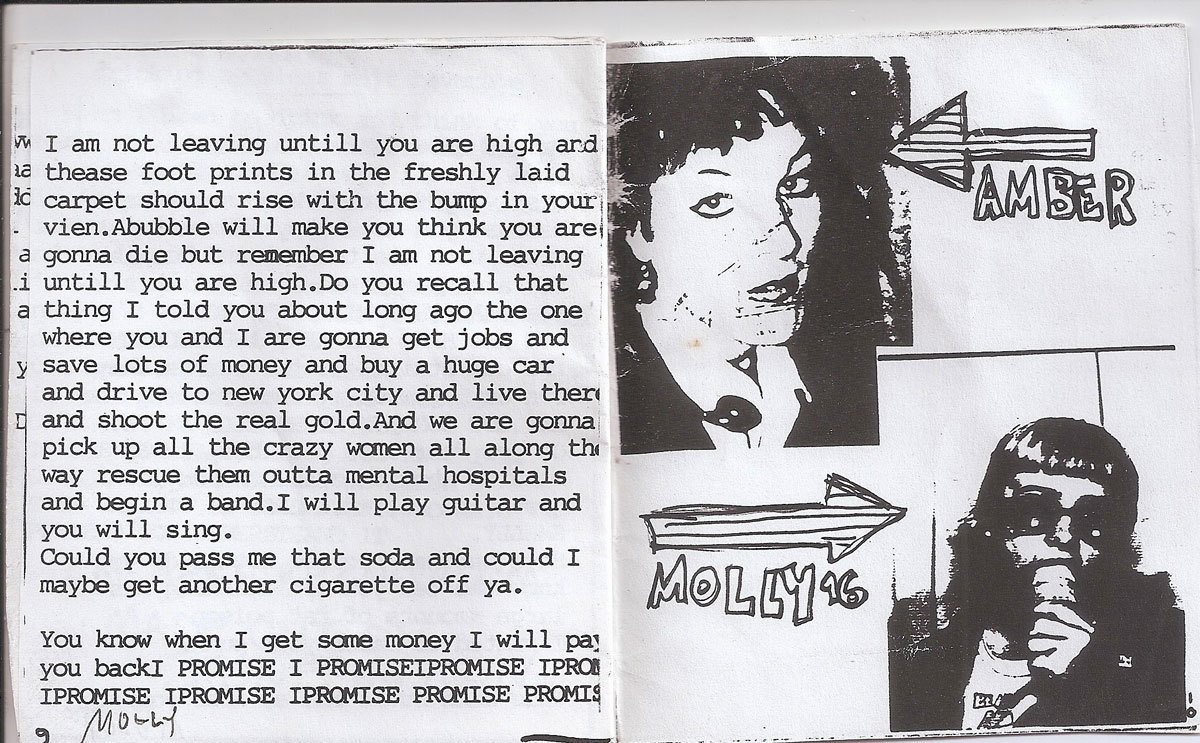

Molly McMahon, aka Molly16, fell into the riot grrrl scene when she was 16 – hence the name. She did artwork for Bikini Kill, had a zine called Rock ‘n’ Roll Fantasy, and was briefly in a band with Kathleen Hanna, with whom she lived for a period. Molly made friends with Courtney Love and was even asked to babysit Frances Cobain (she didn’t, because the reality of being around Courtney became too much to handle – obviously). Other riot grrrls described Molly as a little Courtney Love, intense and obnoxious, but in the eyes of her best friend Amber Dawn, with whom she bonded over abuse, rape and shattered home lives, Molly was an outspoken feminist who would say the things that everyone else thought about but never said.

Then in 1995, when she was just 19 years old, Molly took her own life. Struggling with homelessness, poverty, a sexual assault from which she never recovered, and suffering violence from her father – issues which she openly wrote about in her zine – Molly shot herself in the head with her dad’s gun, in his house.

Amber Dawn, who had been trying to stop Molly killing herself since she was 14, has now made a film about her best friend. 20 years in the making, My Rock ‘n’ Roll Fantasy tells the tragic tale of Molly16, a story of friendship, loss and survival set against the creatively rich backdrop of punk rock culture and third-wave feminism otherwise known as the riot grrrl movement of the Pacific North West. We spoke to Amber to find out more.

Can you tell us a bit about Molly16?

She was my best friend. She was an artist and musician. She did artwork for bands like Bikini Kill, she had a zine that was called Rock ‘n’ Roll Fantasy, where she talked about all the traumatic things that were going on in her life – which was pretty typical for the time. People compared Molly to Courtney Love. She was sometimes a pariah, sometimes someone that people thought was going to be a rock star; she had that personality.

Molly talked openly in her zines about her sexual assault and coming from a broken home; did you talk about that stuff when you became friends?

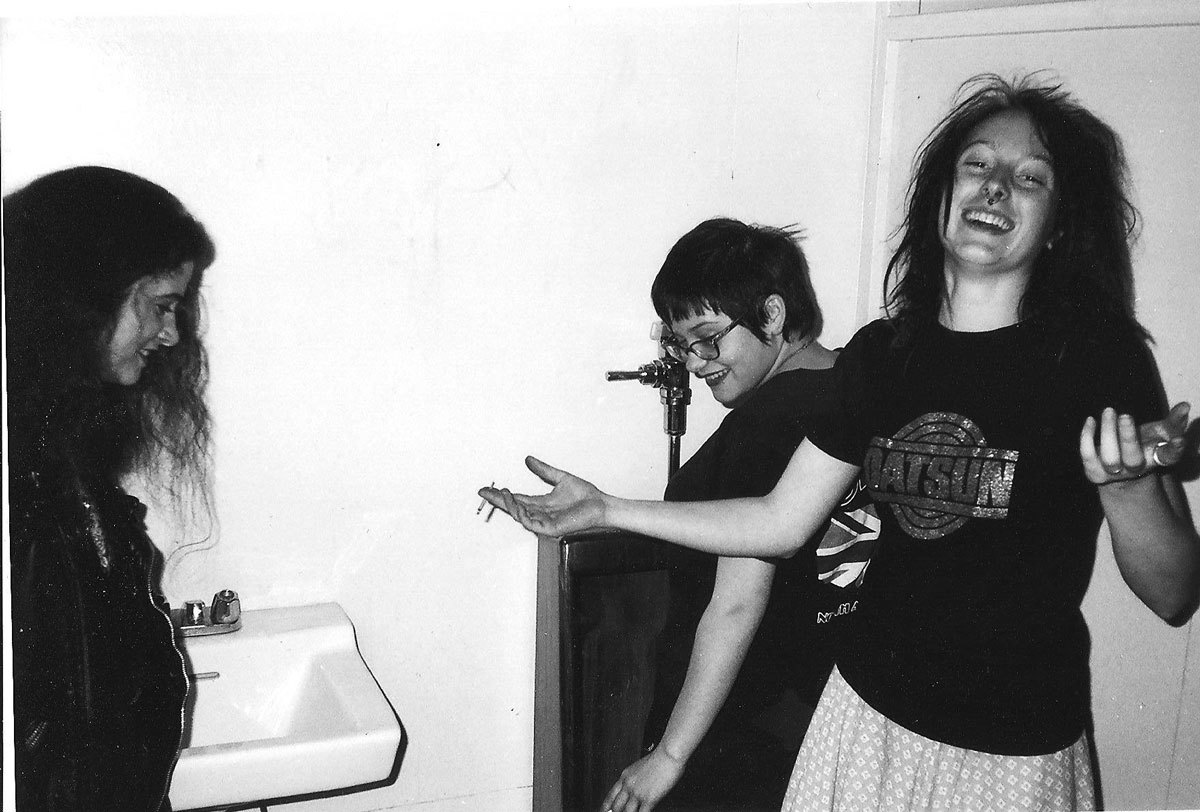

We became friends over this real shared trauma of both of our home lives, and then over sexual assault – we had both been sexual assaulted, and we became very close. She became my champion in a sense. We met in high school in Portland and at 14 we both got matching guitars. She just got really good really quickly; I didn’t play it very much but she was instantly in a band.

Was this before Bikini Kill happened?

This was the same time as Bikini Kill, because Kathleen Hanna started this side project with Molly called The Troublemakers. We were both a bit younger than everyone else and wanted to be a part of this scene. The other riot grrrls in the movement would notice how outspoken and feminist she was at that young age. Going to shows and watching Kathleen and bands like Unwound, we were just always the kids, and that’s how Molly got her name Molly16, because people were like, ‘oh, that’s the 16-year-old’.

In her zine, she interviewed Courtney Love…

She did, but it went way beyond the interview. Molly was in a foster home at that time and then she just showed up with Courtney Love at the door [laughs]. Her foster mum knew that Courtney was her idol at that time. So she showed up with Courtney and says to her foster mum, ‘Can I go back to Seattle with Courtney?’ and her foster mum was like, ‘Okay’. I guess it was really hard to get a phone number out of Courtney, and her foster mum was like, ‘I need some sort of phone number to call her’. So she went back with Courtney, and Courtney actually asked Molly to be the nanny to Frances, but she didn’t end up doing it, she left Seattle right after that. But they just really hit it off.

How did her relationship with Courtney come to an end?

I think the reality of being around Courtney was too much for her to handle. Molly was still so young. Courtney had asked her, ‘You wanna watch Frances?’ and that was kind of like her dream job but at the same time she was under 18 so she would have to be adopted by someone, and it just couldn’t work. Really, she couldn’t be taking care of anyone else at that time, someone needed to be taking care of her.

Molly committed suicide in 1995, when she was 19-years-old. What led her down that path?

She eventually went back to her dad’s and killed herself in her dad’s apartment. But that’s after she had been struggling with poverty and homelessness for a long time, and all those connections she’d had with those women, she couldn’t reestablish. She moved to Seattle and she tried out for Hole, because they had an opening for a bassist at that time. Then she couldn’t really establish anything with Kathleen or Kill Rock Stars or any of those people. And then she was just homeless and working in fast food shops. It was just a pretty sad life, and she never really had a place. When she tried to get away from her dad, there was just no place for her to go. Kathleen took her in but it just couldn’t last.

Were you aware of what was going on with her before she died?

She told me she was going to kill herself. And that’s the very personal part of this story that I feel like I’ve just been wanting to get out for 20 years – having that burden of this person telling me she’s going to do this thing. She had a gun, her dad’s gun. I don’t know how many days before, maybe a couple of days before, she told me that she was going to do it and what to do with her stuff and how she wanted her funeral to be.

And I’d been trying to keep her alive for years. Since we were 14 actually, and I tried to have her have this pact with me, and she wrote this letter and signed it and said she wouldn’t kill herself, even though she tried to several times. And at that point I couldn’t convince her not to, and I didn’t have the energy anymore. I just didn’t.

What did riot grrrl as a movement mean to Molly and yourself?

It was a lot about carving a place for women in the rock scene – at that point Portland was just a male-dominated scene. Sexual assault would happen within that scene but no one was really saying anything about it. With everything that’s come out about The Runaways I think this is still an important thing. Sexual assault within the music community is something that’s been happening for many, many years, but especially within the punk movement. It was carving that space and going to shows where the women would be in the front, a safe place for girls. Being in that space as a teenager, Molly and I went to see Bratmobile – that was the first riot grrrl band that I remember seeing. It just seemed really accessible, the women that were singing were just standing up and singing and taking this very powerful stance in the room. For a teenager it was a very empowering thing to see.

Do you feel like that music encouraged more girls to come out and say they had been sexually assaulted?

Yeah, because the music was about it a lot of the time. Heavens to Betsy had this song My Secret that was about sexual abuse. I’ve talked to so many people for whom that song was so important, because there weren’t that many songs about rape before that. The movement to me is like a sort of show-your-pain movement, where people are making punk rock songs that were also about really personal things happening in their lives, and that’s what Molly was doing too. In her first band she had several songs about different assaults and violence she experienced from her father, and there was a space for that at that time – people were listening to it and encouraging it.

What’s the legacy of riot grrrl today, do you think it changed things?

Oh definitely. I do think it had an impact. There were things about it that were bad that we couldn’t sustain in a way, in terms of having shows that were female-only, which pissed a lot of people off, and it’s not something that I would want to do now – there are a lot of people that are in-between gender, it’s just not the best thing to do. In Portland, and Olympia too, one of the things that’s lasted from that movement is all the rock camps for girls. Young girls are getting this message of empowerment that started with riot grrrl and they’re playing music, and that’s great!