The leitmotif of Berlin-based photographer Rita Lino’s oeuvre is the work-in-progress of the self. Her much applauded, breakthrough book, Entartete (2015), orchestrates ten years’ worth of unflinching, often unkind auto-portraits from unfinished projects. Real, adrift and on the brink of emotional collapse, Rita channels the complexities and vulnerabilities of living inside a body. It is, as she calls it, a “vomit of a book”; a diary-sized object, both confessional and therapeutic.

During an intensive spell of research, Rita encountered The Model: A Book on the Problems of Posing (1937), a little-known photographic guide in which the highly-stylised Hollywood imagemaker William Mortensen outlines the technical requirements for posing the model well. His considerations seem polite and mannered – “wiping away of viscous fluid-spittle from the mouth, tears and unseemly perspiration is a must” – yet there’s something cruel at their core. In Mortensen’s eyes, the model’s emotionality is “irrelevant”. The model is a “machine that needs adjustment”; an “object that MUST REMAIN in a motionless approximation to death.” Years prior, Rita had been told that Entartete would have distressed Mortensen. “I never knew such a world existed,” admits Rita. “It was dark, grotesque and utterly captivating.”

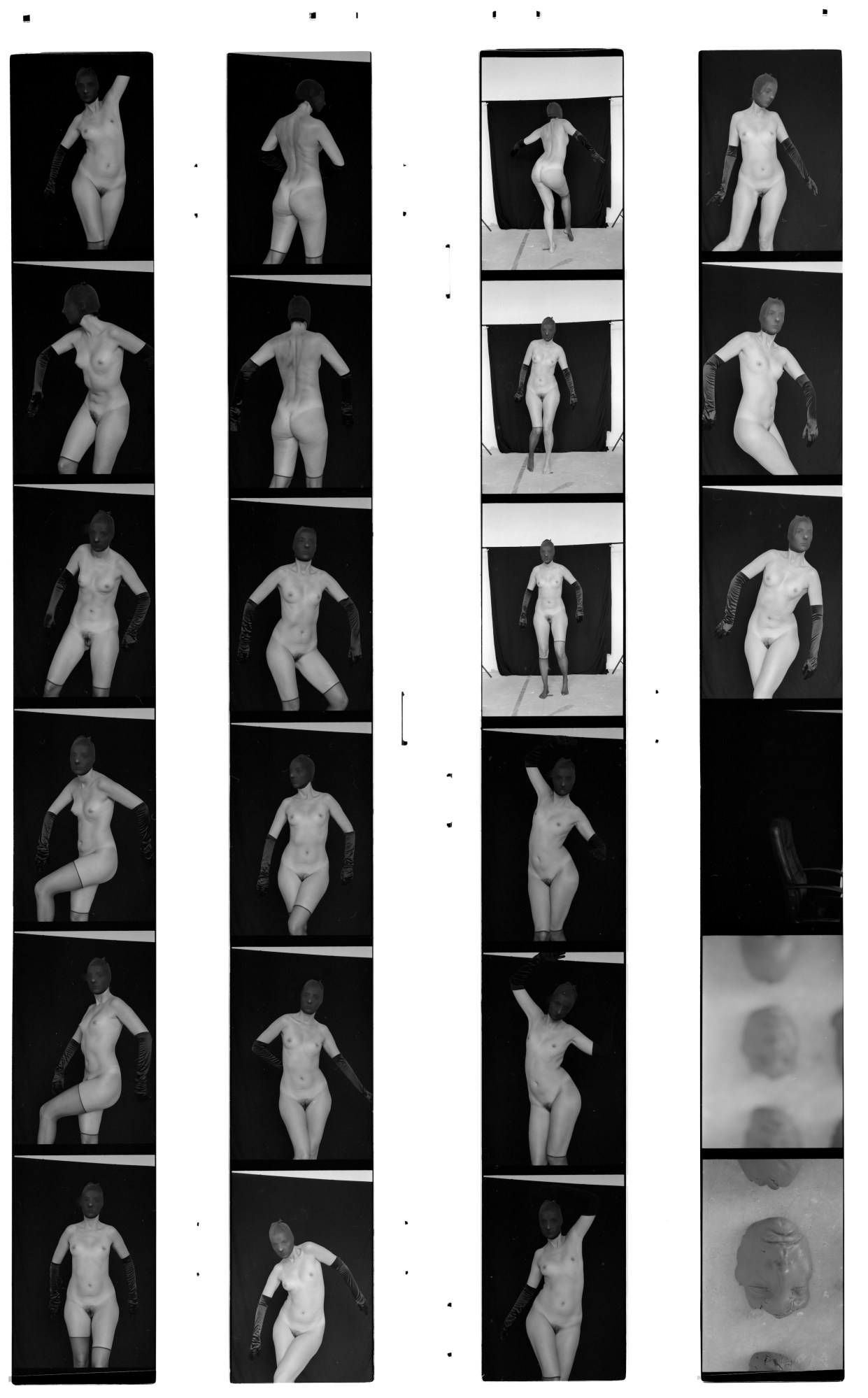

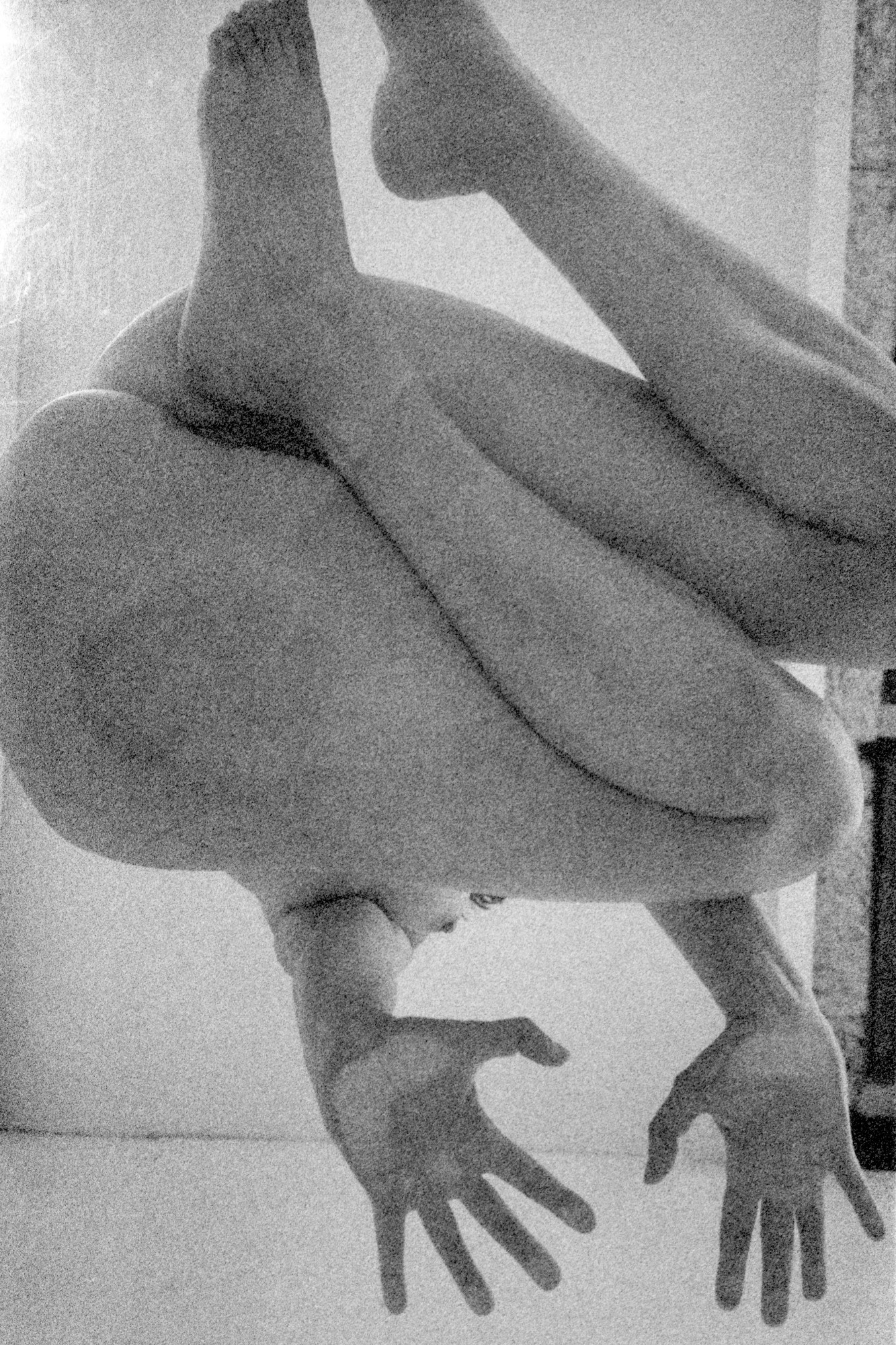

“Replica is what you might call my ‘0.2’ version of Mortensen’s book,” explains Rita. “I was interested in building a kind of Frankenstein. Mortensen’s lucid prose opened my eyes to the possibilities of shedding my ego; a concept I was previously so familiar with. In this way, my subject matter transformed… It became not so much my body but a body. After all, this was never about looking good or looking bad, but rather cutting myself into pieces in order to probe the elements of line, shape and tonality.” Rita’s conceptually-driven book thus constitutes a dramatic departure for the artist. Riffing off Mortensen’s restrictive dictums, she characterises herself not as an instinctive spectacle of emotional lives, but a calculated series of images.

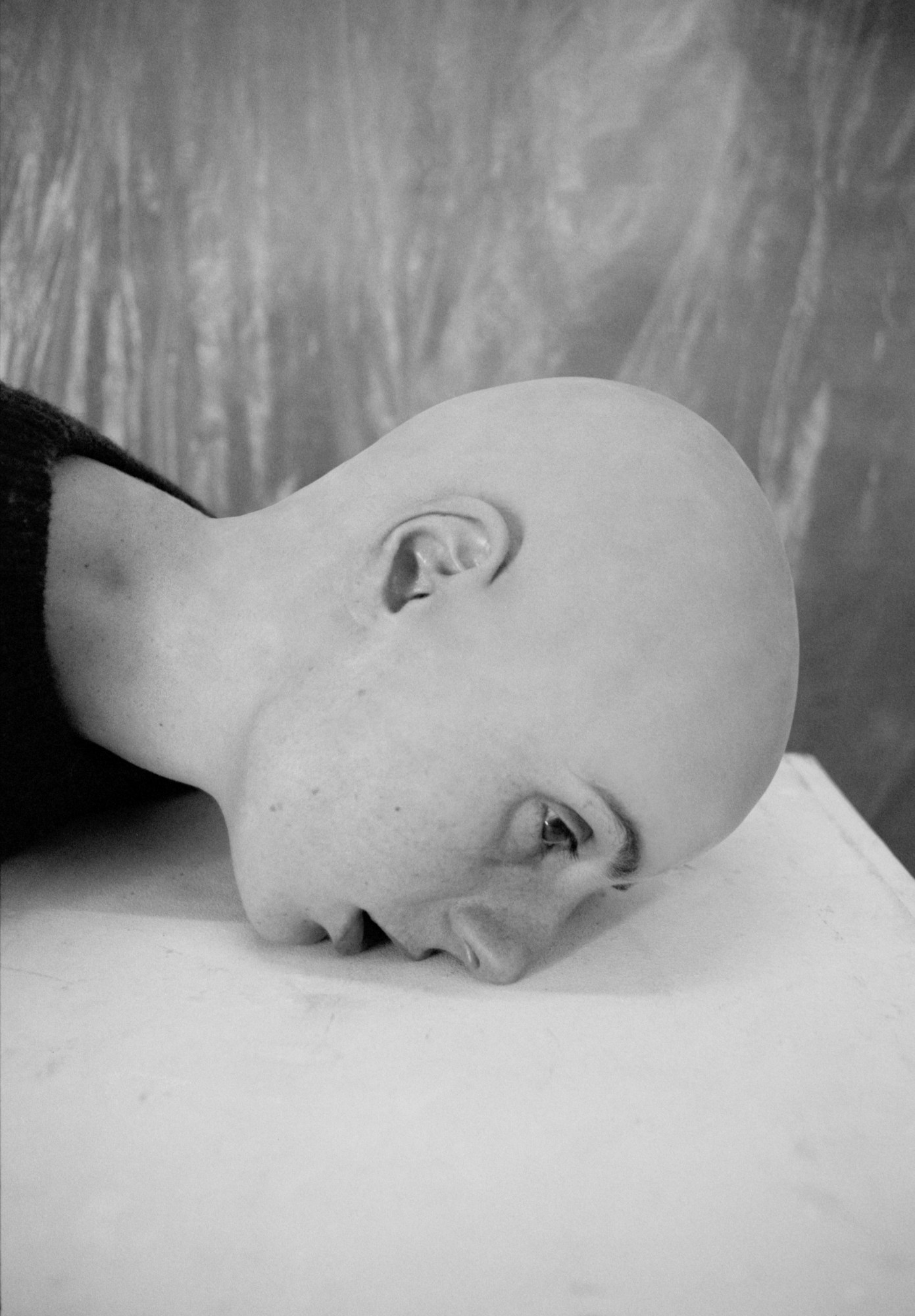

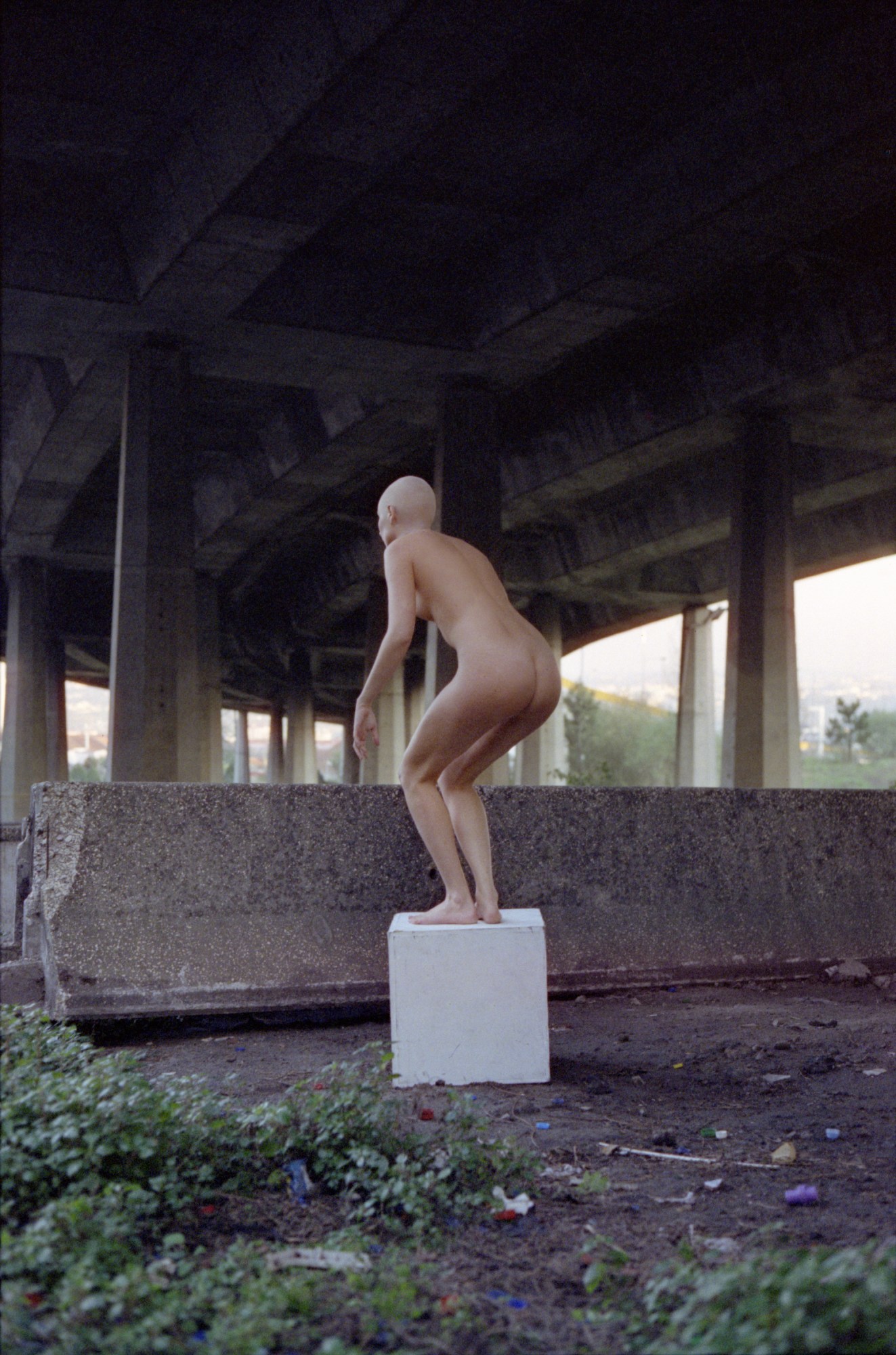

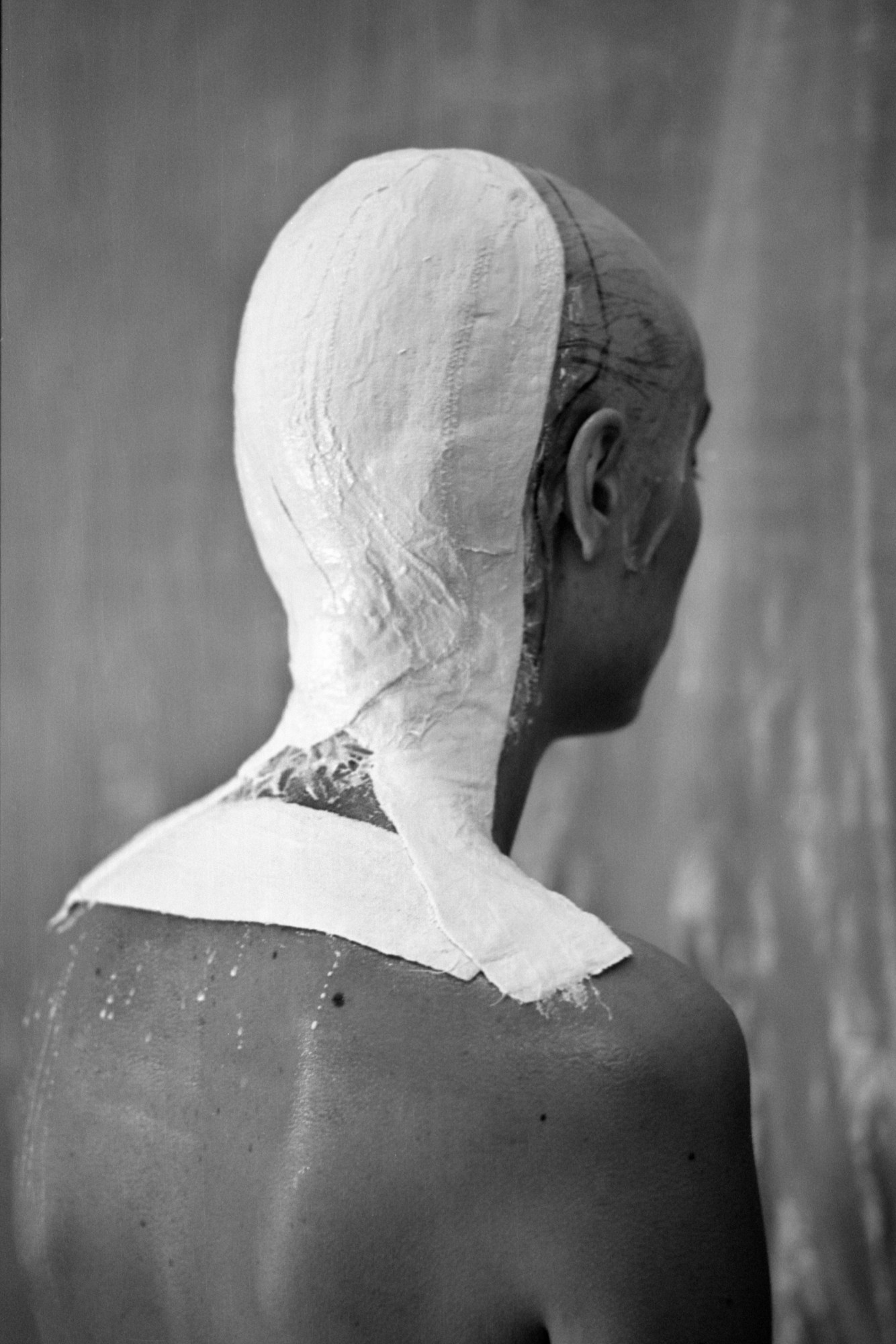

“Does anyone really care about my life story?” ponders Rita, for whom self-cancellation within the frame was an act of liberation. “I began pointing my camera in angles I had never thought about before, and, indeed, ways I would never shoot a model myself.” As if to seek equivalent expression elsewhere, Rita sometimes conceals her face with black cloth or plaster with which she makes masks. Mortensen writes that in the event of “severe scarring, hair loss, baldness or anything which obstructs the fashion of the hairstyles of the day”, frontal views of the model are forbidden. In an extreme and somewhat facetious eschewal of Mortensen’s guideline, Rita postures on a pedestal with a bald head.

The transition from human to object Rita undergoes gets to the heart of the essential representative conundrum of photography. That is, how to convey something three-dimensional via a two-dimensional surface? Where Mortensen disguised his heavy manipulations by rubbing his prints with pumice stones, thereby achieving an etched effect, Rita outwardly flaunts the medium’s artifice. Retakes, chemical distortions and black-and-white film are all put to powerful effect as a way of giving rise to what Rita calls the “body of an image”. She adds: “Manipulating reality is how I make my own.”

Rita’s inventive replications of the body confirm her maturity as an artist actively looking to break the mould, and hers too. Finding currency in objecthood – Mortensen’s fantasy of the death-model – she flies in the face of a contemporary society that champions personal and political will. Replica might leave you longing for something more, but perhaps that something can’t be rendered by the lens anyway. As always in Rita’s work, revelation is within reach, but remains one frame away.

‘Replica‘ by Rita Lino is published by Art Paper Editions.

Credits

All images courtesy Rita Lino and Art Paper Editions