The teeming visual universe of Rotimi Fani-Kayode stems from a seemingly insatiable appetite for life. Before his death in 1989, the British-Nigerian photographer composed a little-seen suite of work that stood in firm opposition to the racism and homophobia of Thatcher’s England – facing down the Iron Lady’s policies with what the curator Mark Sealy calls a “galactic post-punk” energy.

Looking at his work, you imagine that Fani-Kayode only had to look around at his queer community in Brixton to feel that sense of wonder. A poetic sense of transgression continues to course through his images, some of which are included in Tranquility Communion, a retrospective which opened at Ohio’s Wexner Center for the Arts this September. It is the artist’s largest US show to date, featuring well over 100 photographs.

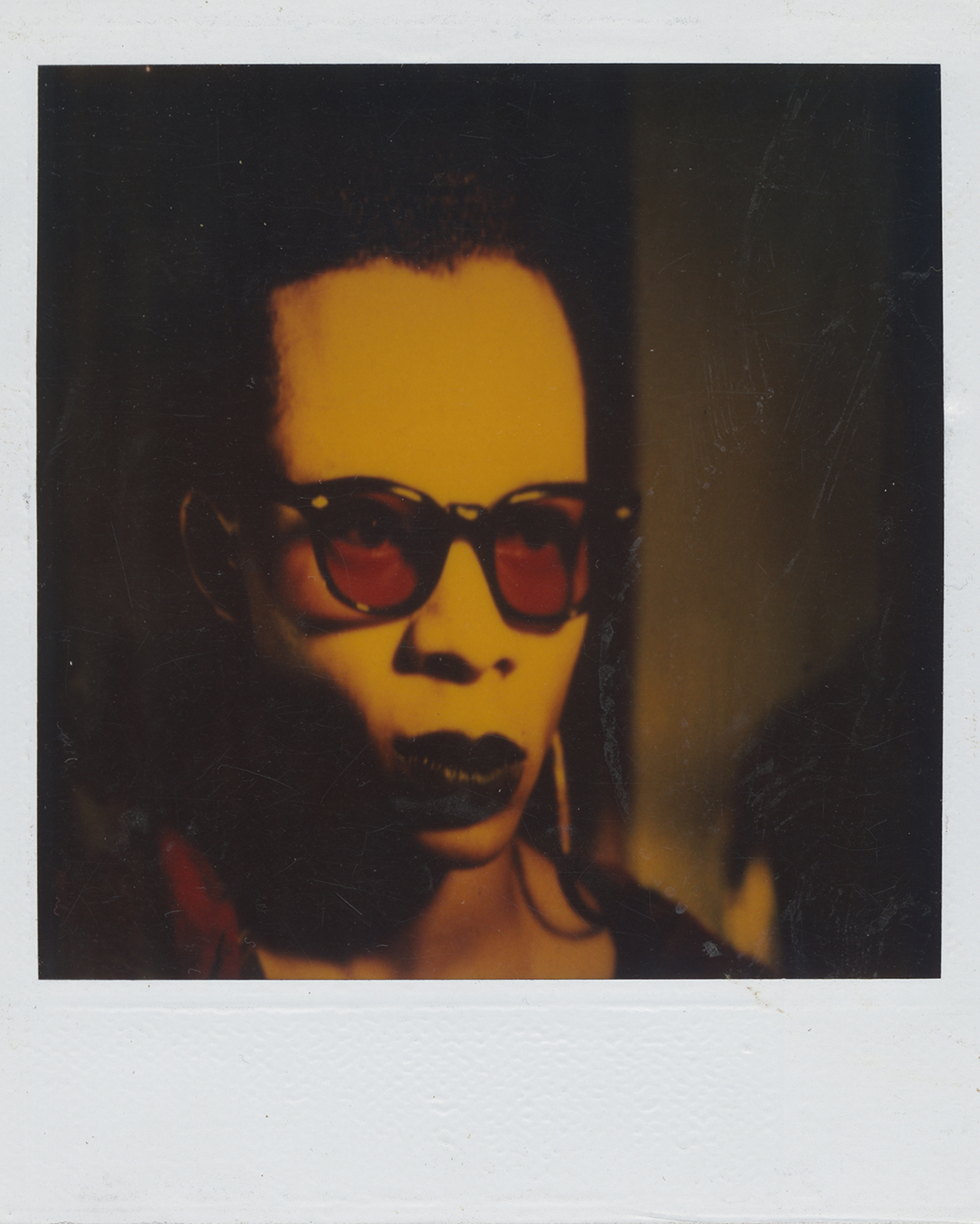

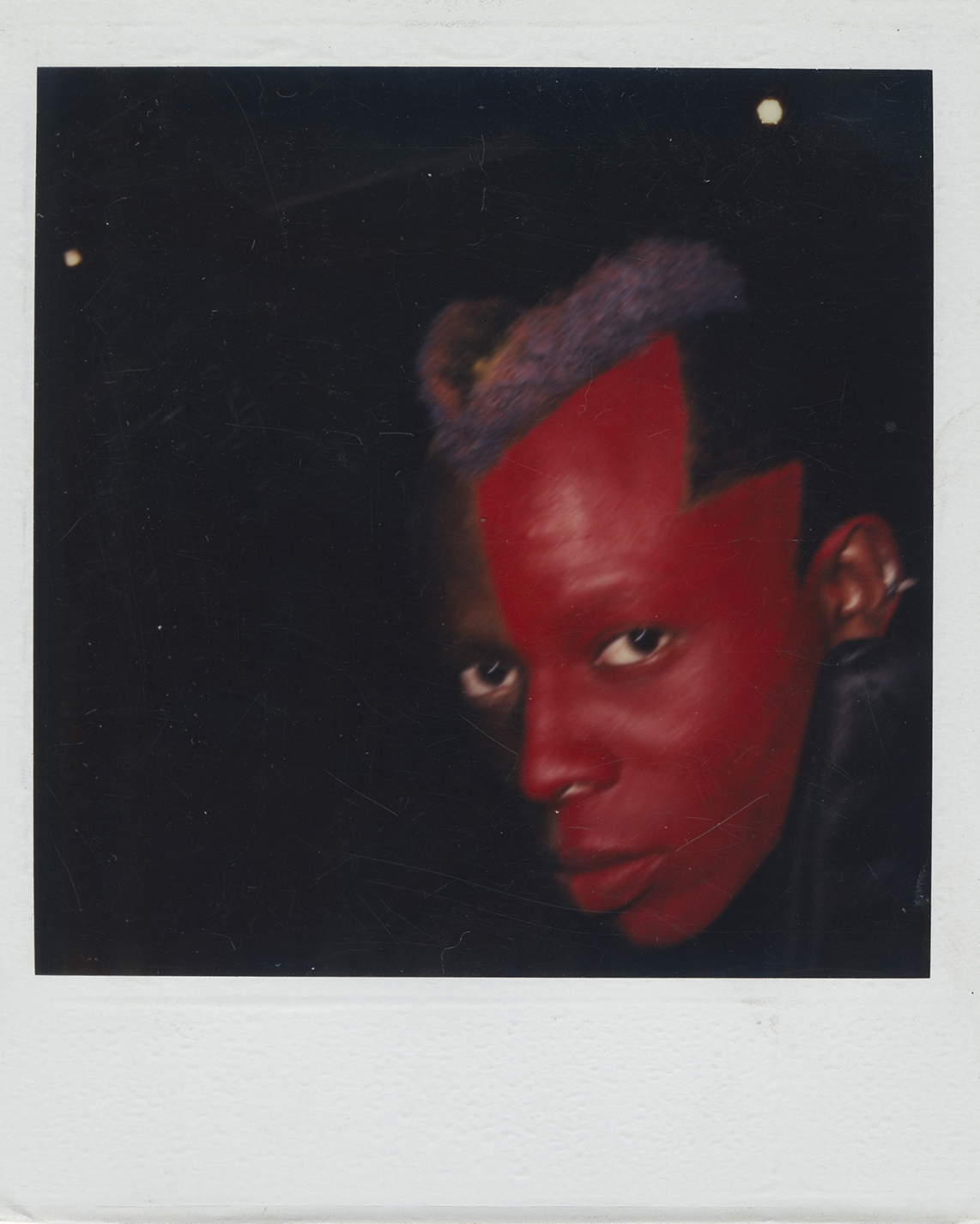

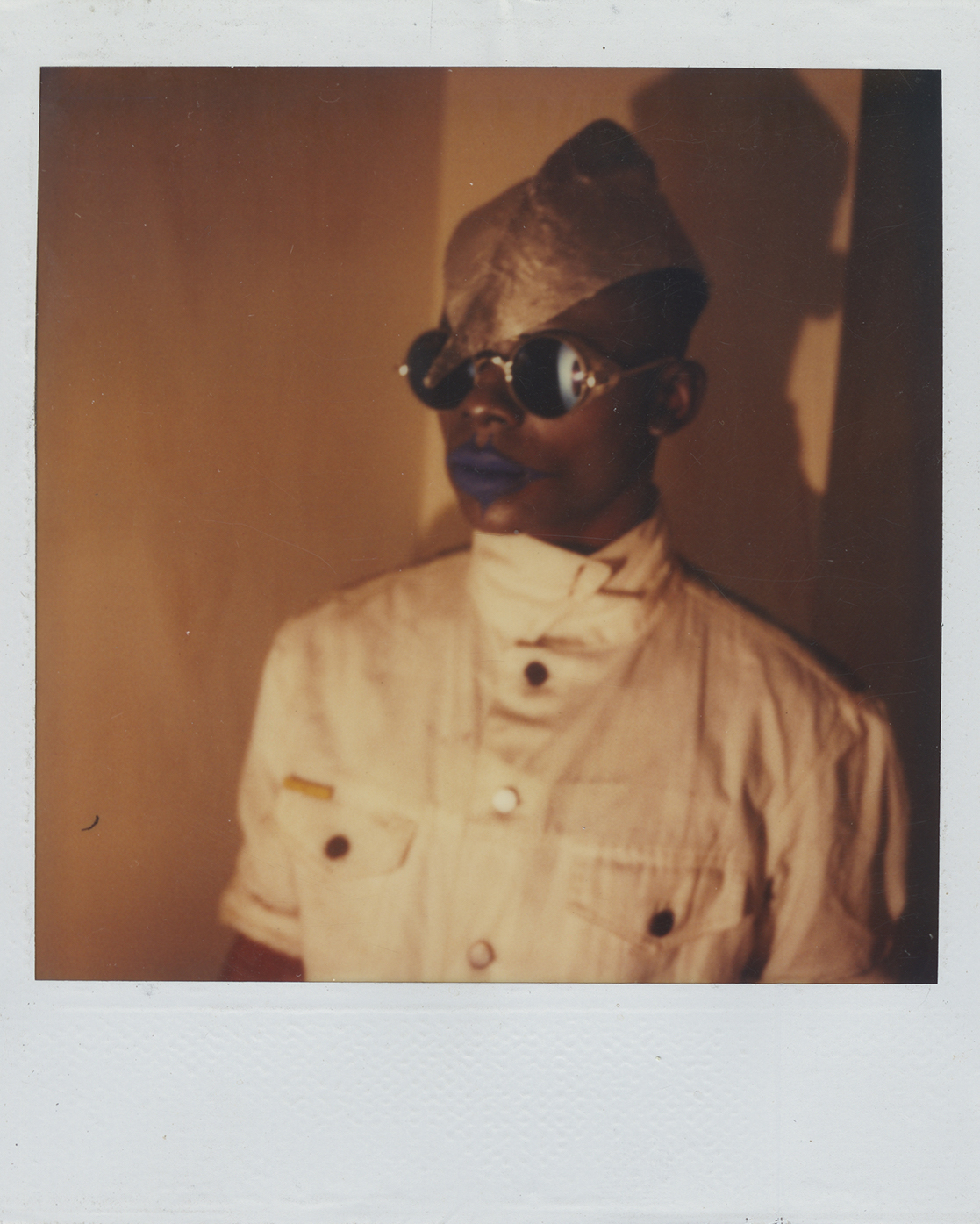

As well as black-and-white shots of glorious male physiques, a highlight of the show is a newly-unveiled series of Polaroids — exclusively shown here — which capture Fani-Kayode and his friends getting ready to go out. Wearing graphic and colourful make-up, the subjects are visions of 80s Black futurism, sporting structured outfits and gazing at the camera with nonchalant self-assurance. They look like they should have been cast in Liquid Sky (1982); Sealy describes them as “disco meets Afro-future.”

“Rotimi was dealing with the “double jeopardy” of being a Black queer artist working in photography in 1980s England” adds Sealy, who is the director of Autograph, the agency for photographers of colour which Fani-Kayode co-founded in the late 80s. Sealy remembers the era as “highly contested political times where Black art practitioners were fighting for visibility.” In the face of a sometimes-unwelcoming mainstream art scene, it was camaraderie with peers that provided emotional support – and solidarity – for these marginalised artists.

Born in Lagos, Fani-Kayode moved to Brighton with his family at age 11, before a formative stint in the States in his 20s. After graduating from Washington D.C.’s Georgetown University, he moved to New York to study for an MFA at Pratt Institute. Fani-Kayode threw himself into the downtown nightlife scene, becoming a regular at Pyramid Club and 8BC; at the same time, photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe and Peter Hujar were making daringly homoerotic portraiture that brought this transgressive underground into the art world.

Upon relocating to London in 1983, Fani-Kayode plunged into the small-yet-fiery Brixton scene of artists and writers, where he met the writer and activist Alex Hirst (his lifelong partner and key artistic collaborator). And in 1988, Fani-Kayode co-founded Autograph as a reaction to the systematic exclusion of queer artists of color from museum and gallery walls.

The New Delhi-born photographer Sunil Gupta, another co-founder of Autograph, remembers Fani-Kayode’s Brixton home studio as warm, inviting, and “frequented by friends for photo shoots.” Yet he also felt another kind of kinship with Fani-Kayode. “We were different among other artists in the group because we were coming from other countries and were familiar with our homelands,” he says, adding “I think we also felt some guilt because we didn’t grow up with the same kind of everyday racism on the way to school.”

“He didn’t have to think about the cosmos in a radical way because he was already living in a complex African cosmology”

mark sealy

Western classical art’s idealised representation of the body was an influence that Fani-Kayode had carried from his days of looking at frescos at New York and Washington museums. But it was a form of Pan-African spiritualism that ultimately guided his photography away from a European gaze. Adebiyi (1989), for instance, depicts a Bacchus-like boy holding an African mask in lieu of Caravaggio’s grapes. “He didn’t have to think about the cosmos in a radical way because he was already living in a complex African cosmology,” believes Sealy, adding that this certainty might have offered comfort as his health began to decline during the AIDS crisis. “Spirituality may well have kept him feeling safe.”

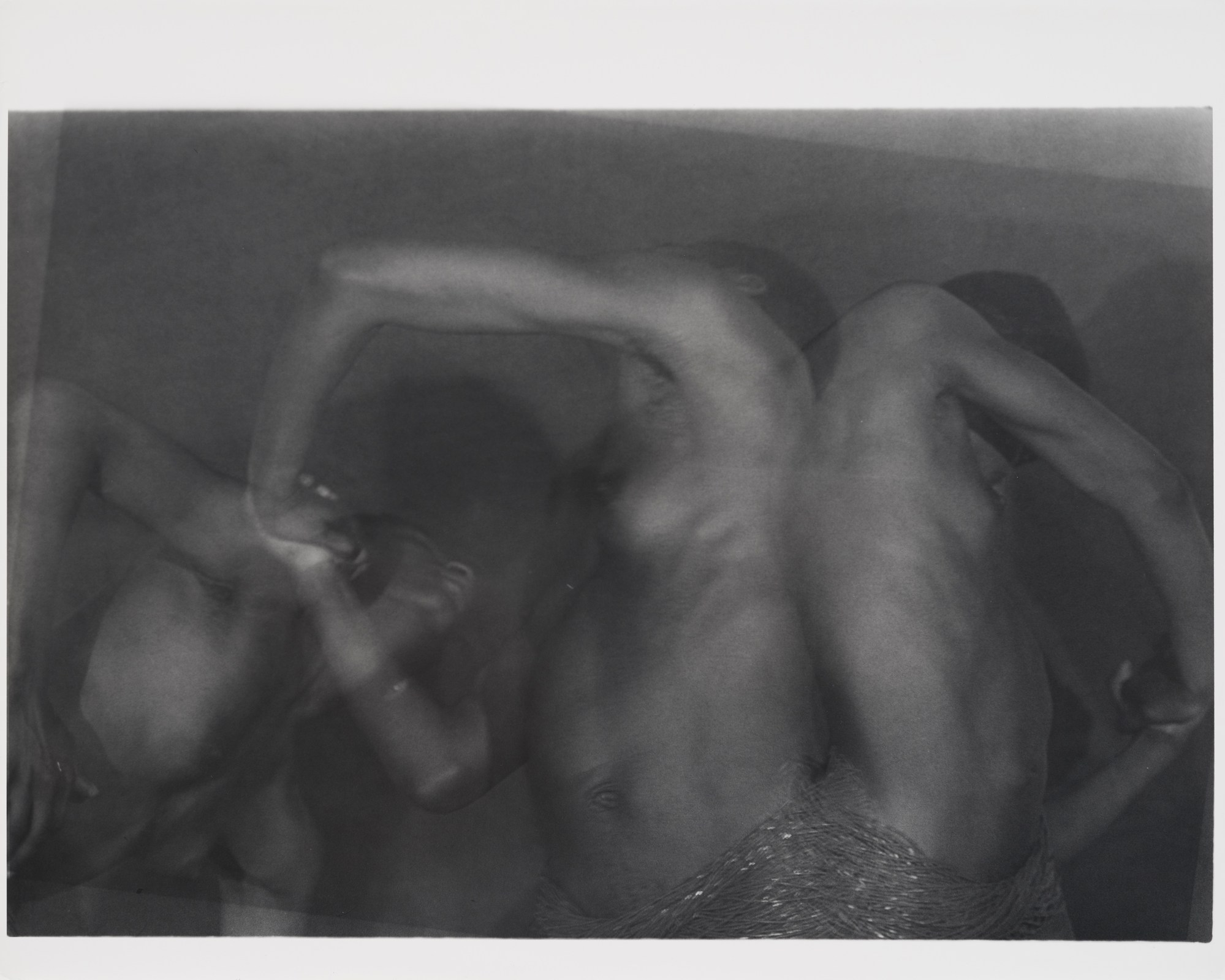

Still, a sense of mortality meanders through the black and white images of Fani-Kayode’s 80s work. In Four Twins (1985), a sequence of four self-portraits is spread across the silver gelatin print like a spectral mark. Pipe, from 1989, shows a man deeply inhaling the titular object like an insistent final jab at life. Meanwhile, the 1986 self-portrait Umbrella embodies a search for safety, and even hiding, through a large umbrella that covers the artist’s face.

Sexuality meets heritage in Bronze Head (1987), Fani-Kayode’s most well-known work. The image depicts the bust of a Yoruba god framed by a nude male’s buttocks. From the spiritual object’s stillness and the muscular body’s kinky gesture emerges a deep respect for ancestry and a yearning for the tactile present. For the artist, that was precisely the point. “My identity has been constructed from my own sense of otherness, whether cultural, racial or sexual,” wrote Fani-Kayode in the 1988 essay Traces of Ecstasy. “The three aspects are not separate within me. Photography is the tool by which I feel most confident in expressing myself. It is photography therefore — Black, African, homosexual photography — which I must use not just as an instrument, but as a weapon.”

All images courtesy of Autograph, London.