Las Soldaderas were the bulleted bandolier-wearing women of the Mexican Revolution, pictured armed to the teeth in white shirts and floor-length skirts, their hair braided under huge sombreros. From 1910, they helped win Mexico’s decade-long war against the dictator Porfirio Díaz Mori, fighting for the rights of the poor and indigenous by overthrowing the class system established by Spanish colonists. In joining the struggle for freedom, the women fighters refuted the traditional gender roles of Mexico’s Catholic and deeply patriarchal society, for the first time.

Inspired by these strong Latina women, the Brooklyn-based Mexican designer Sabrina Olivera launched her label Soldaderas earlier this month. Her first collection includes three styles of printed trousers made from deadstock fabric and tablecloths, found in markets in her hometown of Mexico City.

“[In Mexico], bodies come second after the house,” Sabrina explains. “You can find so many resources and materials for that, but fabrics for nice clothes are rare.” By adopting tablecloths for her designs, she hopes to reclaim domesticity as a symbol not of obligation or exploitation, but one that showcases the strength and power she sees in Mexican women.

Sabrina always wanted to make a difference with her work, but the Parsons-educated designer often felt hopeless to do so in the fashion industry. With Soldaderas she’s able to connect the dots: be creative, collaborative, environmentally friendly, give back to society and fight against misogyny. All proceeds from the sale of the pants will be donated to Red Nacional de Refugios A.C., which provides shelter and support for victims of domestic abuse in Mexico, an issue that has worsened during the coronavirus pandemic this year.

Since the lockdown was first imposed in March, emergency calls to 911 by women surged and have remained high ever since. The same is true of those to the National Network of Shelters, which received 80% more calls than normal. Distressingly, femicide has increased too. According to government data, more women were murdered in Mexico in April than any month on record.

The country’s president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, however, has downplayed the problem, claiming that 90% of phone calls to domestic abuse hotlines were fake, and in a series of austerity measures has slashed the budget for the National Institute for Women almost entirely. He has suggested withdrawing funding for women’s shelters run by NGOs, offering survivors cash payments instead.

Galvanised by the threat to their livelihood, feminists in Mexico have taken to the streets in record numbers wearing purple — chanting and tweeting, “Ni Una Menos” or “Not One Less”. After International Women’s Day there was a nationwide strike called “a day without us,” that used the absence of women to highlight the staggering levels of domestic violence — totalling an average of ten women killed each day. And on September 3, two mothers of victims of gender violence took over the National Human Rights Commission in Mexico City and they have occupied the building ever since. They turned the office into a shelter for victims of violence as a form of protest, and painted lipstick, eyeshadow, purple curls, anarchy symbols and flowers on portraits of male historical figures.

Sabrina knows all too well how stifled you can feel as a woman in Mexico — she didn’t take public transport until she was 25, and living in New York was the first time she felt truly safe. She sees a connection between Las Soldaderas and the women she sees fighting for their freedom today.

Her own exploration into Mexican feminism one summer, led her to the work of Elena Poniatowska, who exposed the social and political treatment of the disenfranchised in society, especially women and the poor. Her testimonial narratives were based on both historical facts and the accounts of marginalised people and include an archival photo book called Las Soldaderas. “There are still a lot of people who think it’s still a myth that these women were part of the fight,” Sabrina says, but her grandfather often told her of going to war with some of the most famous women soldiers.

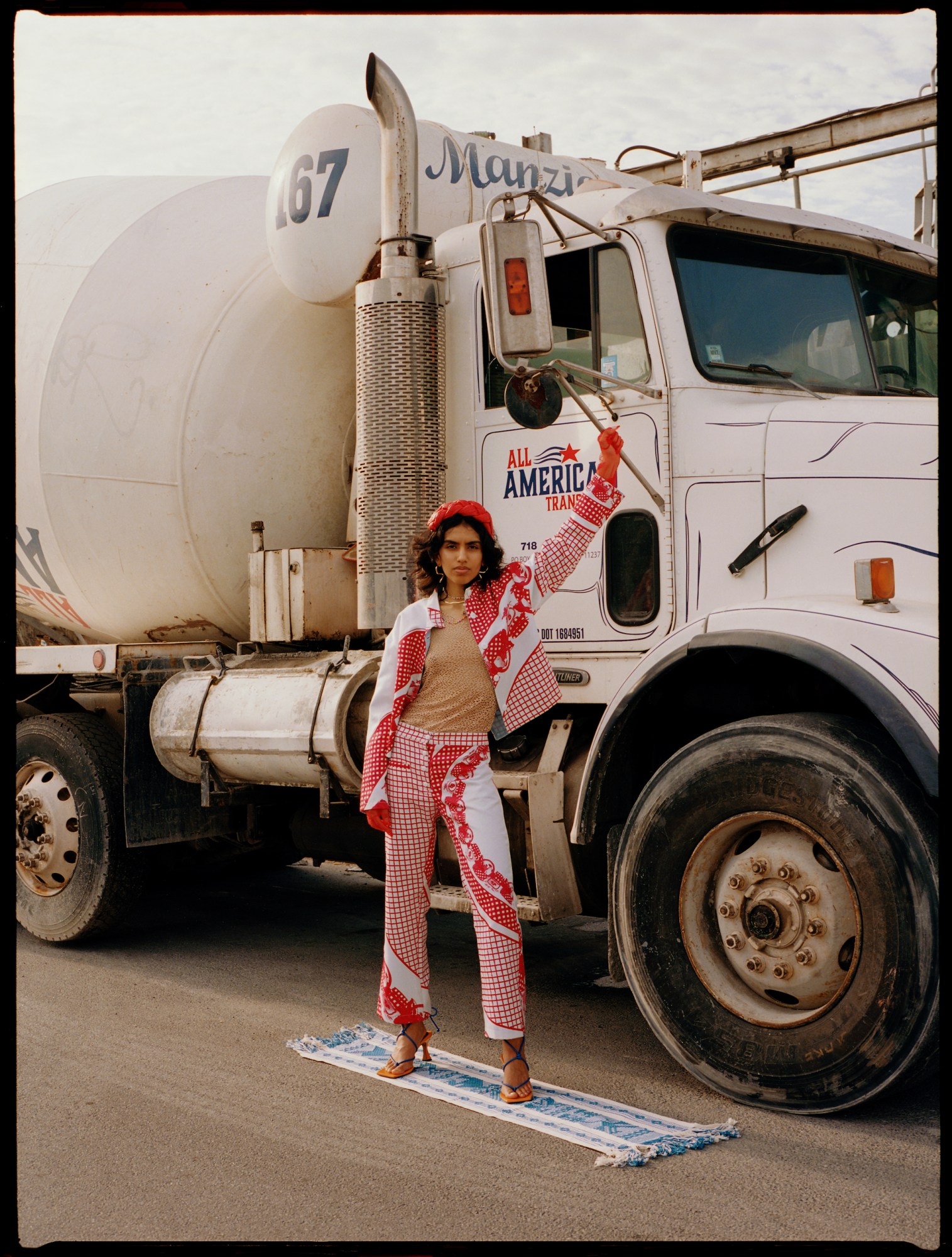

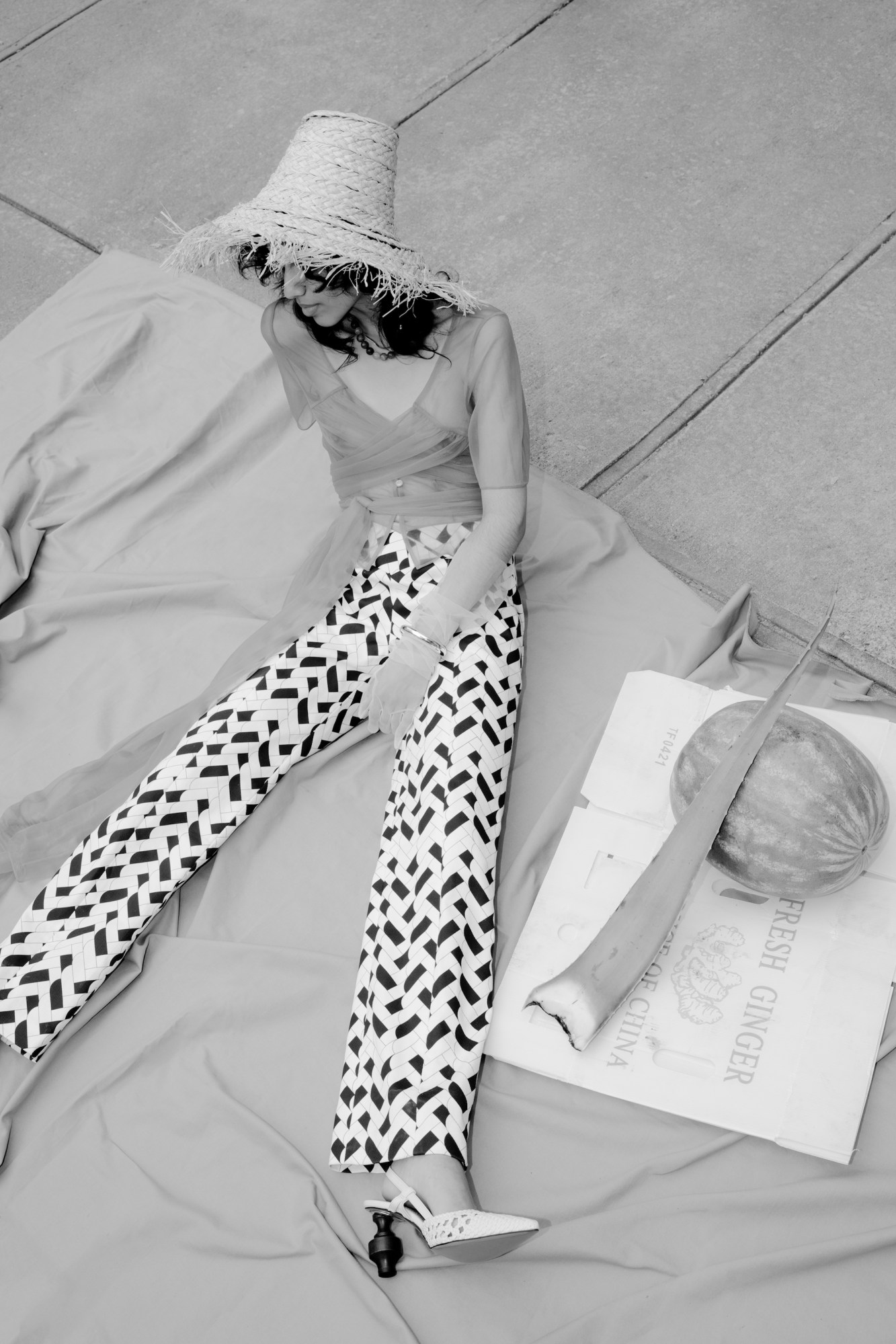

Spurred by quarantine and inspired by Las Soldaderas, Sabrina began designing the trousers that are now available for purchase. There’s the red and white tablecloth pants made from a fabric often found in cheap restaurants in Mexico and a pair of printed produce pants, aptly photographed in a fruit and vegetable market in Oaxaca. The utilitarian pocket pants, in cream and neon pink, with their visible seams on the knees, reflect the armour often worn by soldiers.

In images taken in and around New York City, photographer Meghan Marin captured Aria Puga in all of Sabrina’s handmade looks (styled by Margaret Galvin). There are square-toed, vintage-inspired boots in the style of a beloved pair Sabrina bought in Amsterdam and accessories made from the excess leather. Matching jackets, knitted tops and braided headscarves influenced by the long braids worn by Las Soldaderas. Plus, paper earrings that use traditional Mexican milagros, religious folk charms used for healing purposes and as votive offerings. If you’re heartbroken, Sabrina explains, you can pin a heart shaped piece of paper to the veil of the Virgin Mary to cure you.

Hailing from a family of chemists and physicists, including her single mother who raised her while working full-time, Sabrina’s choice of career stands out. But she might never have become a designer at all had it not been for a fellow designer friend from Colombia, that she met in New York. “I remember going to the Women’s March after Trump won the election,” she says. “I went to my friend’s house and she was sewing a huge flag that was painted with the words ‘woman galore.’ She finished in 10 minutes and I remember thinking that was so badass. I want to do that. I want to create a flag against the patriarchy.”

Sabrina Olivera’s Soldaderas collection can be pre-ordered on her website.