This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Royalty Issue, no. 370, Winter 2022. Order your copy here.

São Paulo’s unforgiving nature is implied by the urban landscape you encounter on coming in to land at Congonhas, the city’s downtown airport, amidst an unending, Gotham- like sprawl of concrete. Once on the ground, however, the superficial bleakness of this dense grey mass is counterposed by the intense life force that courses through its labyrinthine streets: home to 22.5 million people, the city is the largest metropolis in both Brazil and Latin America.

Indeed, if New York is “the city that never sleeps”, São Paulo is the city that never rests. By day, this is made apparent through the conversational din in rammed metro cars, symphonies of revs and honks from its perpetually gridlocked rhizome of overpasses, and the overheard whir of helicopters ferrying monied paulistanos from point to point. It’s a sonic vignette that captures “the friction among São Paulo’s many citizens,” says Pedro Pinho, a 30-year-old photographer based in the city. “Marginalised communities and affluent individuals share space in a way that most often is oppressive,” he continues, highlighting the implicit socioeconomic and racial division that colours São Paulo life. “On the other hand, it is a city of possibilities. A place where you can build – or fight to build – a life on your own terms.”

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

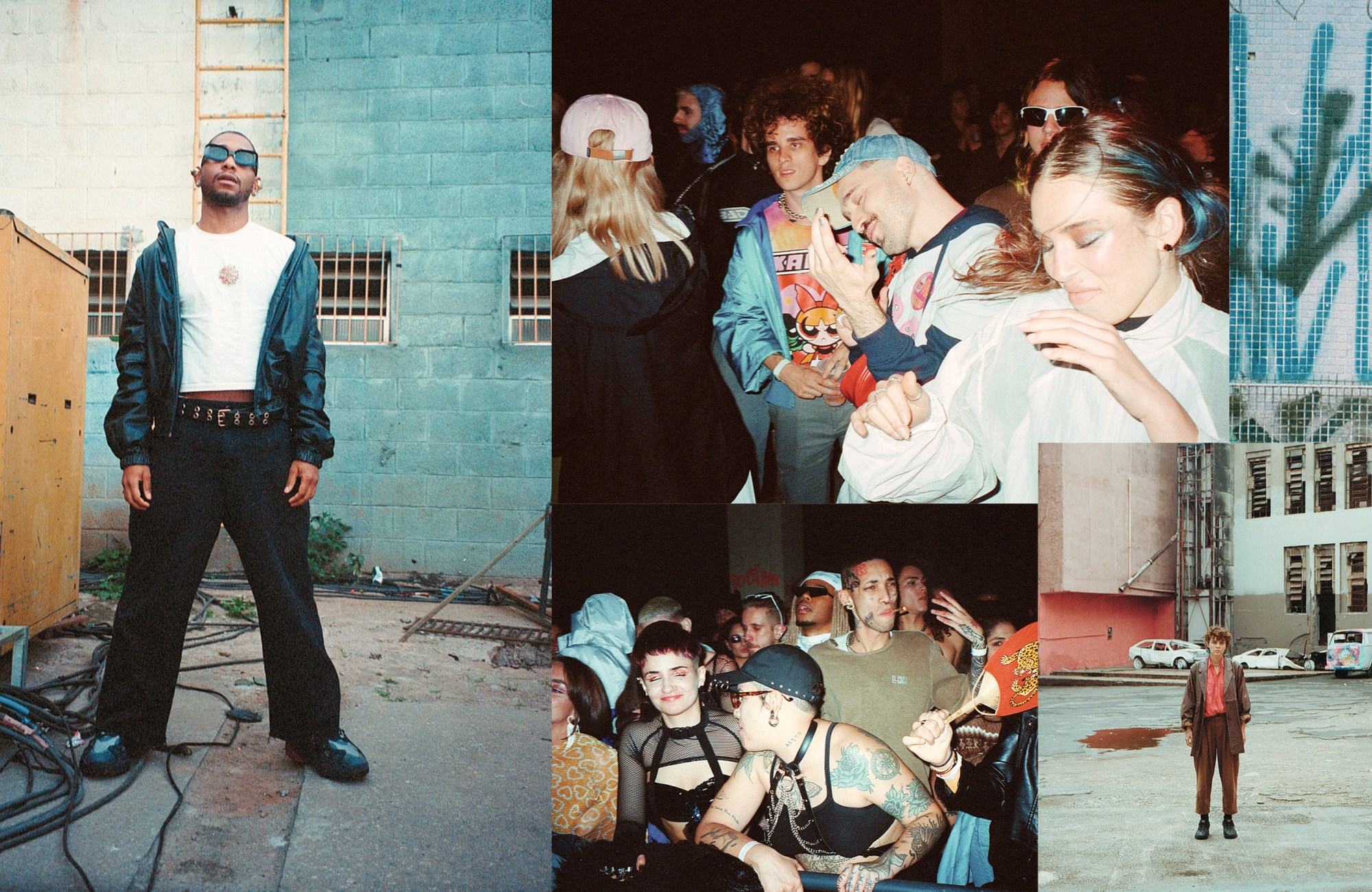

If São Paulo’s day is governed by a punishing hustle culture, its night is a space for catharsis. Plush rooftop bars; no-frills botecos; bottle service clubs; raves beneath city centre slip roads and in defunct office buildings and more are forums for the release of existential pressures. For Pedro, São Paulo’s electronic music scene in particular offers “a counterpoint to the ideas of productivity and the ever-working man – an opportunity to celebrate meaninglessness, find yourself happy while lacking, and find abundance in not being enough.”

“For young people in particular, partying becomes an identity–an attempt to completely cut ties with the oppressive nature of the day and its responsibilities,” Pedro continues. Granted, the same could be said for electronic music scenes in major cities the world over, which have long served as crucial havens for marginalised bodies – particularly for Black, queer and trans people – and those seeking conduits for self-actualisation beyond the remit of conservative social norms. What perhaps makes São Paulo’s underground such a distinct and noteworthy example of a progressive nightlife culture, though, is how both its organisers and audiences understand the value of partying. While they certainly offer opportunities to blow off steam, parties such as BATEKOO, Tesãozinho Inicial, Chernobyl, and the defunct Tormenta are widely framed as projects geared around the social and cultural emancipation of São Paulo’s most systematically marginalised people. And not all of these are, it should be stressed, ramshackle, if-you-know-you-know underground affairs – many of them are major productions that draw crowds in the thousands. “Here, it’s about rethinking the system, imagining new ways of social interaction and strategies to go against forces that are much larger than you,” Pedro affirms.

A quick glance at Brazil’s political context – both current and historic – explains why. At the time of writing, the nation is weeks away from a second round vote that is set to topple Jair Messias Bolsonaro, a president who, during his tenure in office, has pursued some of the most aggressively fascist politics that the world has seen in recent years. “It’s been four years since a far-right, conservative, pro-gun, misogynistic, patriarchal government came to power and we represent absolutely everything in contrast to it,” Pedro says. “Our very existence is considered an affront to its values, as if we were crumbling society with our way of life.”

Still, the political charge of São Paulo’s underground scene long predates Bolsonaro’s arrival. “We’ve always been here – even if, for a long time, we existed far from the structure’s eye. But we were fighting against what current Brazilian fascism represents before it becomes an anti-Bolsonaro trend,” says Igi Lola Ayedun, a native paulistana and founder of HOA, Brazil’s first Black-owned gallery and artistic residency. To her, what distinguishes São Paulo’s party culture is its “historic commitment to the forces that have truly built this city – indigenous, Black and queer people from all over the country.”

This narrative of sociopolitical engagement has become especially prominent over the past decade or so. “When I started to attend electronic music parties in the mid 2000s, it was all about trance, house and EDM music that was made in a very elitist environment,” Igi recounts. “They were parties where everyone was white and bourgeois.” The embrace of baile funk – a musical genre hailing from the predominantly Black communities of Rio de Janeiro, and since exported across the world – in São Paulo’s electronic music underground in the early 2010s was a significant turning point, she says, catalysing a “renaissance in which this former ‘marginalised’ culture came to occupy the centre.” “The door has opened for a new generation of artists like KENYA20Hz, Evehive, Mu540, DJ Bassan, RHR, L’homme Statue, and many others who just aren’t interested in copying European approaches to electronic music.”

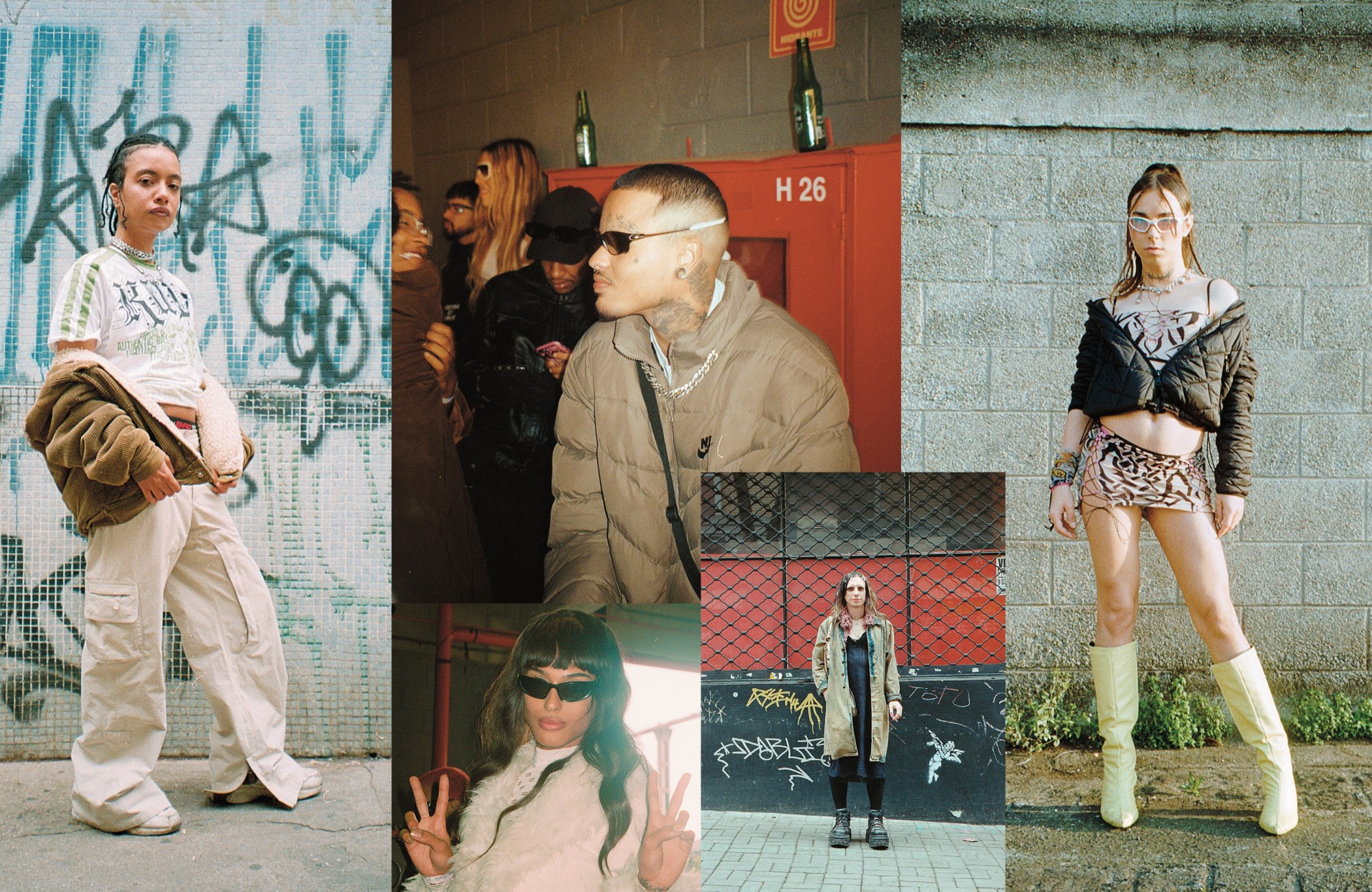

An important consequence of this shift has been necessary economic redistribution in a scene that previously reproduced systemic inequities, particularly concerning race and gender. “This new generation understands nightlife as an ecosystem that can truly provide economic emancipation” for communities once disenfranchised from electronic music scenes, Igi says, with Pedro offering the example of BATEKOO, one of São Paulo’s buzziest parties founded by Maurício Bahia Sacramento, which has a “staff and line-up exclusively made up of Black people,” he explains. “Not only is that a direct step towardsaffirmative action, but it also directly impacts the lives of the people whose culture and music we’re celebrating.”

As crucial as this sense of social duty is to the city’s party culture, it’s important to note that it never comes at any detriment to the quality of the music that’s being played. A rough, bassy mix of sounds spanning techno, baile funk, grime, breakbeats, R&B, hardstyle, pop, dancehall, and too much more to list, summarising the sound that defines São Paulo is a near- impossible task. This is in large part due to São Paulo’s status as the country’s foremost melting pot – a culmination of “migration flows from across Brazil and the world–and we are an enormous country,” Pedro says. “That is reflected in this feature: KENYA20Hz comes from Rio de Janeiro, Delcu and White Prata come from the south of Brazil, Maurício was born in Bahia… Even though there is this kind of conflict between different regions of Brazil, a unique mix of influences and backgrounds is present here – and that makes for really amazing music.”

One word that cropped up near-ubiquitously when trying to describe São Paulo’s particular sensibility was chaos. While it may certainly bear negative connotations in the context of the city’s oppressive daily grind, by night it takes on a joyful timbre, signifying a hallucinatory blur of people, lights, and sounds that anyone can freely melt into. “The main thing that São Paulo has is that it’s made of dreams,” says KENYA20Hz, one of the DJs you’re about to meet below, “and dreams happen at night.”

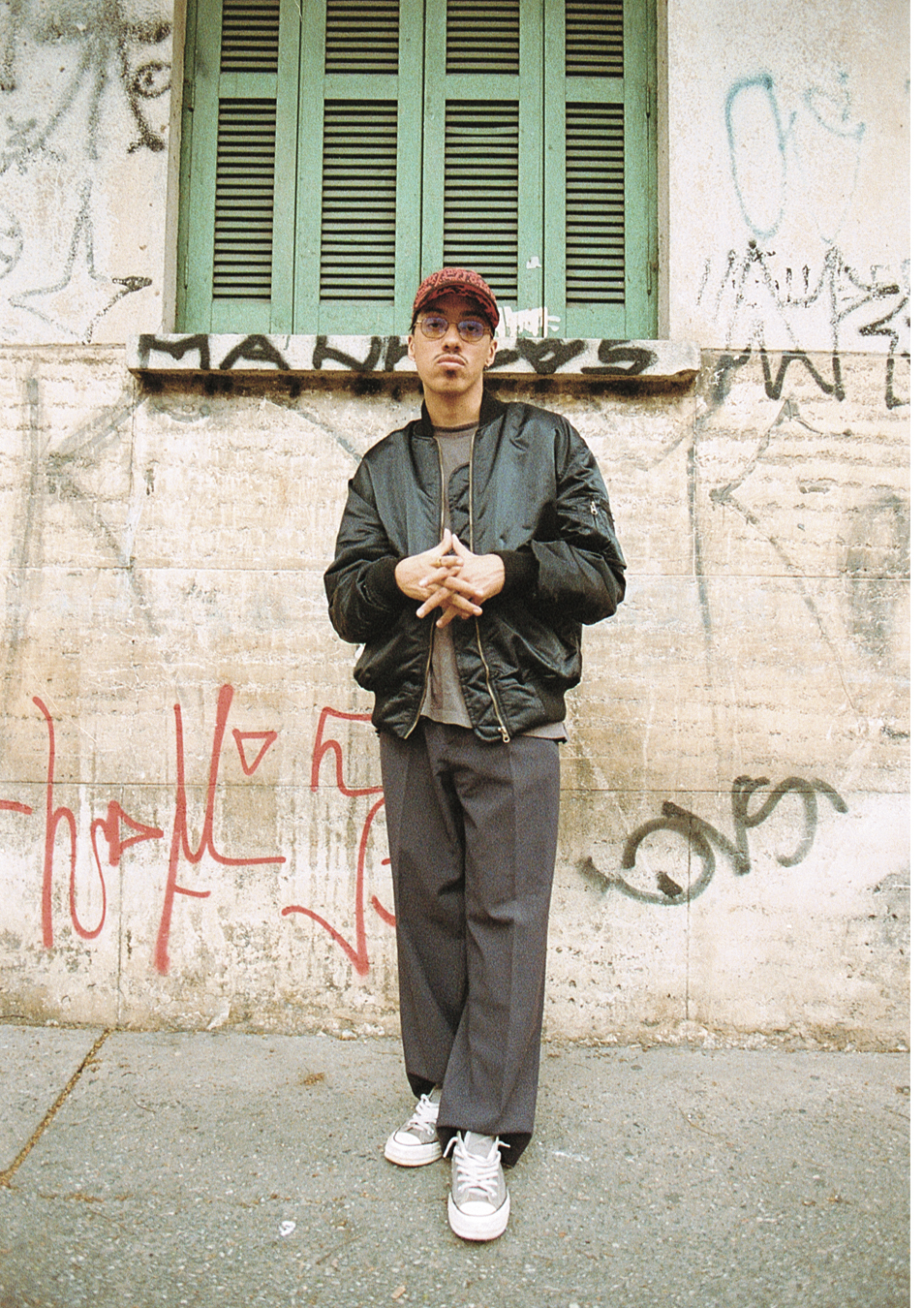

RHR

“The city swallows you. If you don’t have a sense of urgency, you can’t get by.”

“The phrase that defines São Paulo is ‘monochromatic stone jungle’. It’s grey to the bone,” is how Roniere Santos – aka RHR – describes his hometown. A moody description, for sure, though it’s exactly this stony spirit that gives his brooding-yet-brutal DJ sets and productions their character. “São Paulo is a grey city most of the time, which shapes you whether you like it or not,” he says. “I think this subjectively leads me to play sounds tinged with melancholy and chaos.” His perspective on the city harks back to his teenage years growing up in the city’s South Zone, watching his parents working around the clock. “I always had the perception that they never stopped,” he says. “That’s kind of how I feel about the city – it swallows you. If you don’t have a sense of urgency, you can’t get by. All of this chaos in São Paulo – this rush that you see on a daily basis – is reflected in my DJ sets and productions, whether it’s by mixing different types of genres or superimposing several layers of textures.”

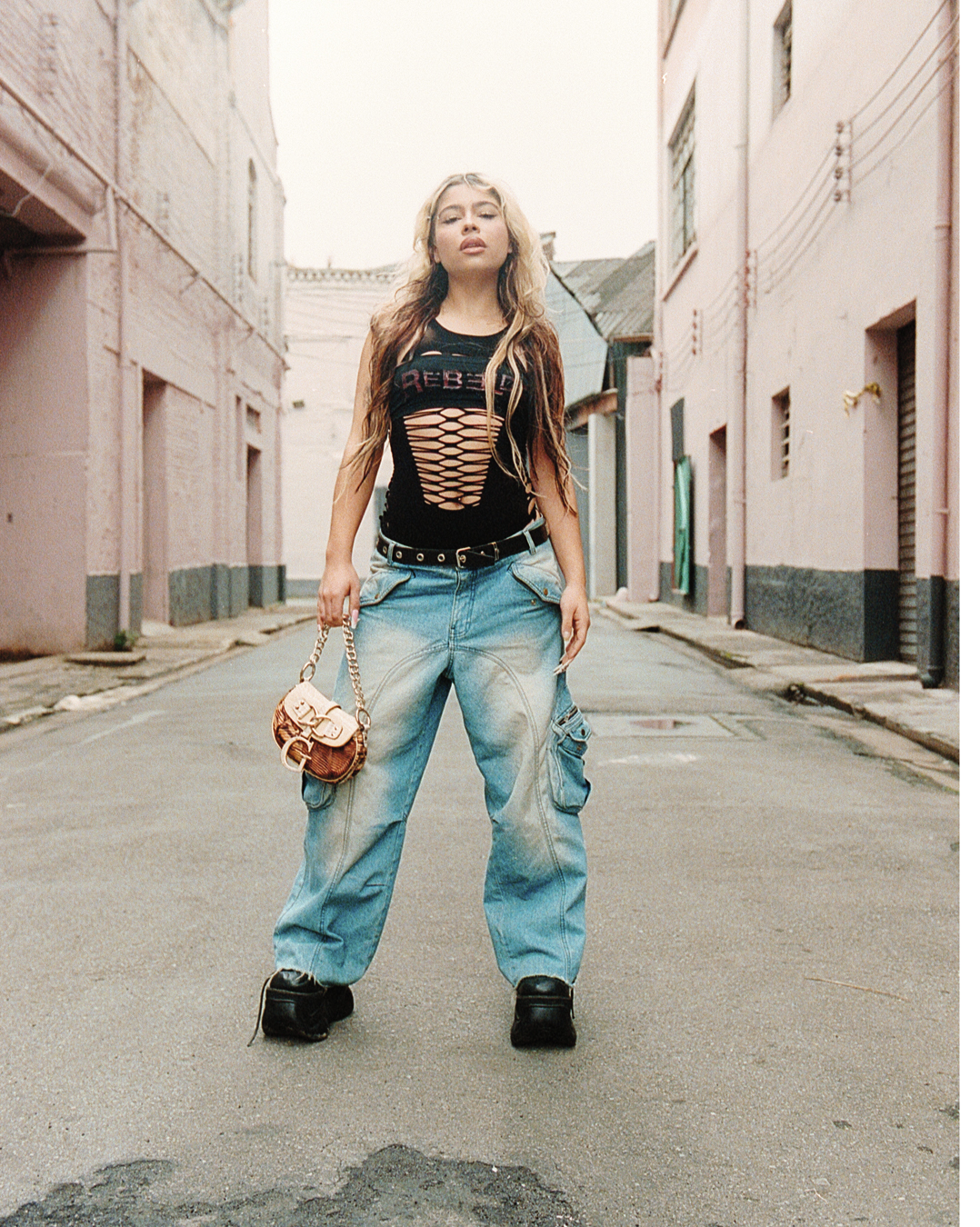

KENYA20Hz

“I always wanted to get to the point where I could understand my performance as a ritual, and I can say that I bring my most primal and ancestral memories to the stage.”

Originally hailing from the northern suburbs of Rio de Janeiro, Kenya Rosa Sacramento – known behind the decks as KENYA20Hz – arrived in São Paulo more recently than most featured here. While many may be put off by the city’s harsh architectural aesthetics, that was a main draw for the 27 year-old artist when she made the hop in the first half of 2021. That along with “the idea of living in a city known for being an inexhaustible cultural source that attracts people from all over the world,” she says. This yearning for variety and versatility is something that announces itself through her sets – deep, dubby, sensually percussive journeys. Her yen for ultra-low frequencies, as her DJ moniker well implies, brings an ineffable quality felt deep in your bones, and she describes her creative practice in almost spiritual terms. “When I started my musical project, I always wanted to get to the point where I could understand my performance as a ritual, and I feel like I can already say that,” she says. “I bring my most primal and ancestral memories to the stage. From drum sounds from Afro-religious centres to Japanese horror films, everything that causes me a feeling of curiosity and nostalgia finds its way into my creations in some way.”

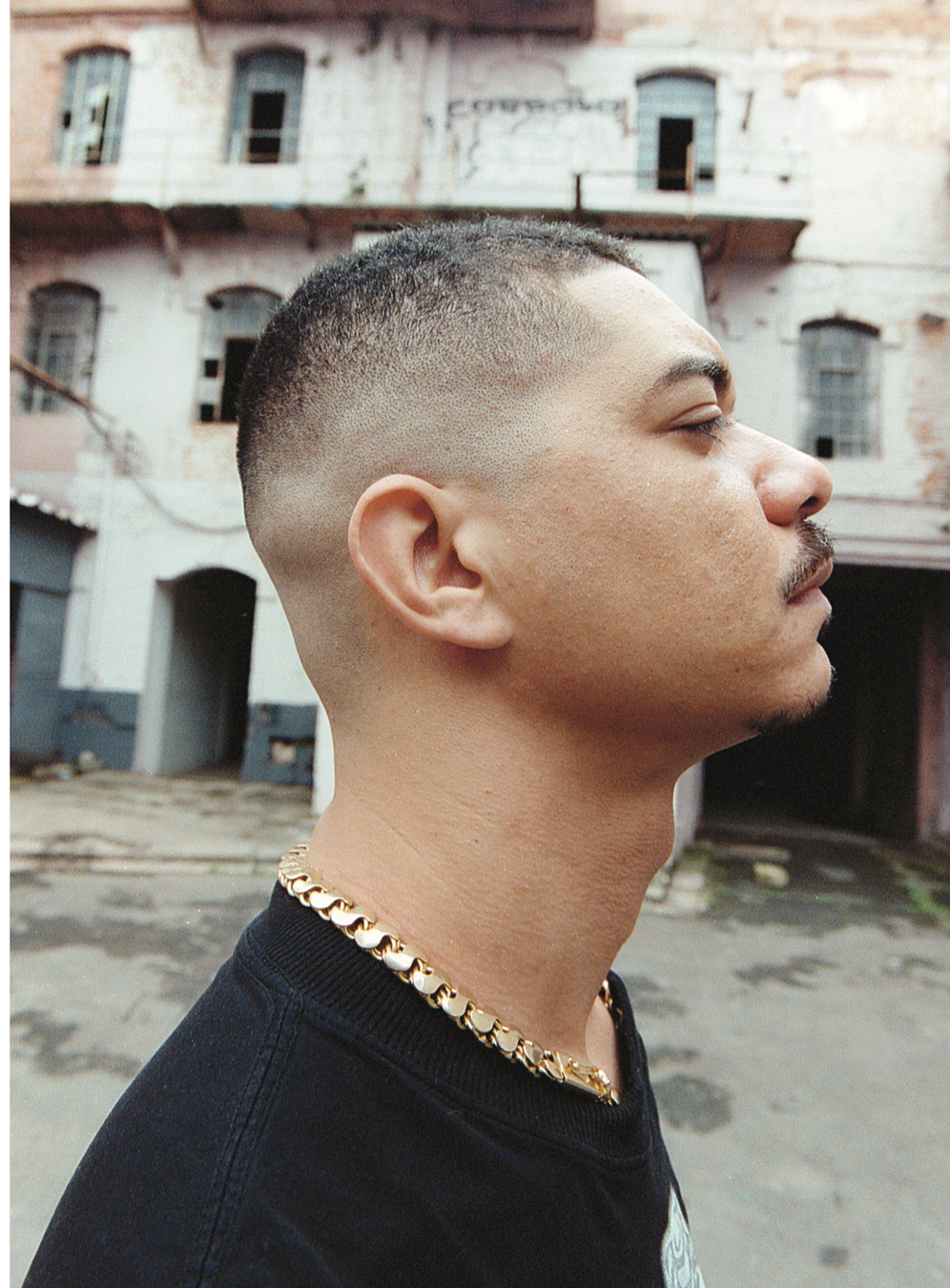

Maurício Bahia Sacramento

“Enough of just finding black people only at political demonstrations in search of rights. We want to meet and to be happy, too.”

Few people have championed the notion of using partying as a conduit for politics quite like Maurício Bahia Sacramento, the founder of BATEKOO. Founded eight years ago by the 27-year-old – who hails from the state of Bahia – “as an unpretentious party aimed at Black people,” he says, the party has since blossomed into one of the most significant and cherished presences in the São Paulo scene. Hosting a number of the artists here on its stage, BATEKOO has become a proud “manifesto of the Black and LGBTQIA+ movement” and a vital force in democratising access to cultural events to those living in São Paulo’s periferia. “São Paulo is a city where about 40% of the population is Black, but the vast majority of these people live in the outskirts,” he explains. “Public transport does not cover these more remote suburban regions, and the access of these people to culture is much more difficult. BATEKOO managed to circumvent this and strengthened the flow of Black people passing through the city, allowing them to leave the periferia and come to consume culture in the centre.” An unabashed celebration of “the cultures that are produced in the periferia and Black communities around the world,” BATEKOO has played a key role in recentering São Paulo’s electronic music scene around Black cultural production, with a staunch by-us-for-us mentality at its core. Beyond its political impetus – and just as crucially – it has also created a space in which Black joy abounds. “A thing that I’m proud of is that BATEKOO is one of the only places that encourage Black people to come together, and be happy and proud to be Black,” Maurício says. “Enough of just finding Black people only at political demonstrations in search of rights. We want to meet and to be happy, too.”

Cashu

“By creating our own parties, we were able to open up more space for other women, and not be at the mercy of the curatorship of men.”

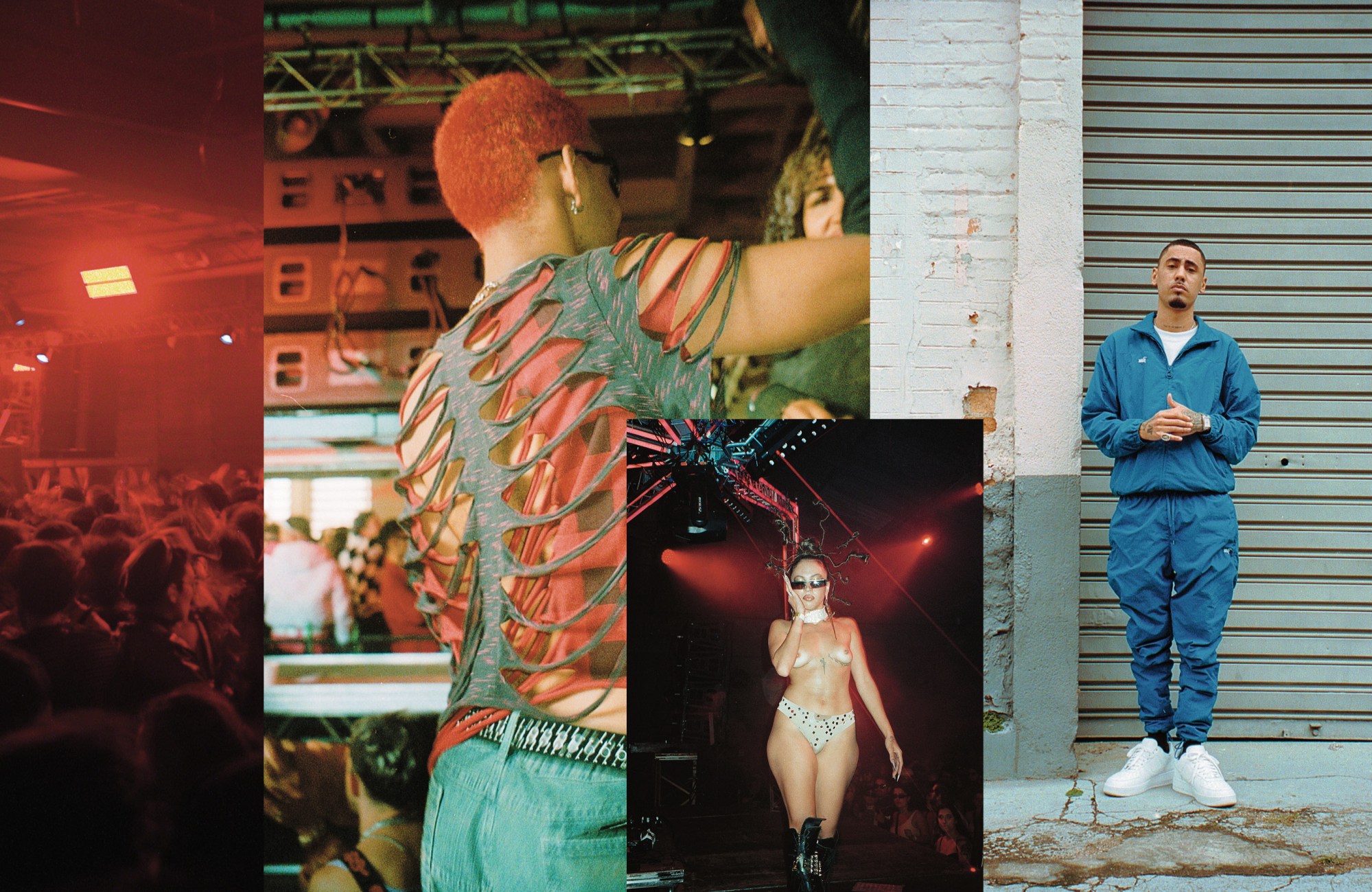

As the founder of Mamba Negra – São Paulo’s preeminent electronic music event – Cashu is a doyenne of the city’s night culture. Her interest in activating the city through nightlife was piqued during her days as an architecture student fifteen years ago. “My work was inspired by the problems of the city and the people who live here,” she says, discussing her observations of how failed government regeneration projects in São Paulo’s centre came to host impromptu gatherings.“In 2010, street parties began to appear downtown, and I started to develop an interest in these occupations of idle spaces.” After a few years of DJing and producing parties in buildings left derelict, Cashu threw the first Mamba Negra in 2013: “A very important year, politically, there were demonstrations due to the high price of bus tickets and also the high school revolution,” she recalls. “The city was teeming with collectives that were occupying the squares and streets of downtown.” The decision to start the party was motivated by the desire to create an infrastructure that would benefit the performing artists, but an equally significant motivating factor was a desire to “address the lack of women leading the biggest parties,” Cashu says. “By creating our own, we were able to open up space for other women.” Today, Mamba Negra draws thousands to parties like the one photographed here, held at Fabriketa. Its ethos of social advocacy continues, and has played a key role in catalysing scene-wide changes. An example is the trans list, an initiative pioneered by the underground trans-operated party Chernobyl seven years ago to guarantee free access for trans, non-binary, and gender non-conforming people, which was swiftly implemented at Mamba Negra. “It’s now become a default in São Paulo,” Cashu says, ”and, as such the scene has become a much more welcoming space.”

Kontronatura

“São Paulo’s nightlife is a place that many marginalised bodies have inhabited for a long time.”

Growing up deep in São Paulo’s South Zone, Achille dos Santos – aka Kontronatura – found himself more or less cut off from the cultural wealth his hometown brims with. “For a good part of my adolescence, there wasn’t even a subway that went downtown,” he says. When he moved to the city centre in 2016, after leaving his family home following a turbulent time coming out, it was almost as if he were “discovering the city anew, experiencing other facets which, until then, were unknown and inaccessible to me.” After a tumultuous arrival in the city, characterised by harsh encounters with violence and inequality, his experiences with São Paulo’s nightlife scene served as something of a saving grace: as a Black transmasculine person, it offered a space of self-actualisation. “São Paulo’s nightlife is a place that many marginalised bodies have inhabited for a long time,” he says, noting how trans people, in particular, have “inhabited the night, whether attending parties or engaging in sex work.” While it wouldn’t be accurate to say that São Paulo’s electronic music scenes have always offered a safe space for the systematically marginalised, Achille notes that efforts have been made to make them such. “Nowadays we’re seeing a greater openness at these parties, and these existences are also celebrated, admired, and highlighted beyond a socially imposed place of marginality,” he says, with Mamba Negra, where Achille is currently a resident DJ, serving as a case in point. The sets he plays to the party’s vast crowds focus on fast, glitchy music with historically Black roots – dancehall, kuduro, funk, Baltimore club, footwork… “What I most enjoy, though, is playing with the audience’s sensations, creating psychedelic and percussive environments that make you shake your butt, even if you don’t want to.”

White Prata

“The city is vertical, the air is polluted, the sky is grey and the weed is really bad, but with the right people, you can have a lot of fun.”

“Sweetie, welcome to the stone jungle!” is how Elisabeth Prata Moraes Silva – a.k.a White Prata – would introduce newcomers to the city she’s called home since 2016. “Here dreams grow and die amid toxic rain and flying rats. The city is vertical, the air is polluted, the sky is grey and the weed is really bad, but if you dissociate enough you can live here as long as you want – and with the right people, you can have a lot of fun.” As intense and cinematic a description it may seem, it’s one that makes perfect sense on hearing one of her blitz-speed productions. “The kind of music your parents wouldn’t want you to listen to around them,” her tracks and live sets brim with hammer-like baselines, shrieking synths, eerie whistles, and jangly melodies, aptly echoing her description of São Paulo’s innate sound: “Birds screaming for sex amid the sound of machines, concrete, and sweat.” Outside of her own performances, you’ll often hear her tracks as bona fide weapons in the sets of a number of the artists here – who, in a testament to the familial nature of the city’s scene, Elisabeth cites as her “great references and inspirations. I’m very happy to be a contemporary of such a cool crowd.”

DJ Bassan

“The periferia is where I feel welcomed – there’s a real sense of inclusion and respect.”

Originally from Porto Alegre, in the far south of the country, Gaia Bassan —aka DJ Bassan — was drawn to São Paulo six years ago by its inimitable lustre. “In the south of Brazil, we have a huge lack of cultural incentives, and São Paulo is where everything revolves,” the 25-year-old DJ and producer says: “It’s where big dreams happen.” Since taking that fateful decision, many of her own have come true, earning her a bold reputation for sets that bring together “Brazilian funk, vogue beat and club music, mixed in a thick, juicy and spicy way,” she says. “Something that shakes your mind and your butt.” Beyond the dancefloor, though, she’s proven herself a testament to the sociopolitical ethics that have shaped São Paulo’s scene, imparting her skills by way of “a public policy programme in the state of São Paulo, which enables young people from the favela and low-income areas to graduate in cultural production,” she explains, noting the importance of spotlighting talents that aren’t incubated or heard in the city’s centre. “In the periferia, the night and the music are extremely lively and powerful. It’s where I feel welcomed – there’s a real sense of inclusion and respect.” It’s here, she says, that you’ll hear São Paulo at its most authentic – the sounds that “really show that we are unique.”

Febem

“Don’t summarise the city by the coldness of the centre because there is another São Paulo beyond that. The periferia has its independence, its warmth and its joy, even if it’s often forgotten by the system.”

In London, grime is not typically associated with the city’s electronic music scene. In the genre-irreverent blur of São Paulo’s, however, it proudly finds its place. Spotlit at parties including Batekoo and Peroli’s Perifa no Toque, one of the protagonists in bridging the gap between genres is Febem. Known for his slickly delivered, pithy flows over syncopated tamborzão percussion, and his collaborations with fellow MCs like CESRV and Fleezus: his baile funk-suffused rhythms are natural fits in the sets of DJs like Mu540 and RHR. Just like them, he sees his music as an expression of the city’s identity – specifically that of the often overlooked periferia. It’s there, he urges, that a more human side to the city reveals itself. “The periferia has its independence, its warmth and its joy,” he says, “even if it’s often forgotten by the system.” Though divisions between the music and party cultures of the city’s outskirts and the centre have historically held strong, thanks to artists like Febem steps have been made towards eroding these boundaries. “We’ve started to see the breakdown of niches. When I started, there was a lot of prejudice from rap audiences towards electronic music, in part due to the whitewashing and elitisation of electronic music in São Paulo,” Febem says. “Nowadays, many people who go to rap parties also like to go to electronic music parties and vice versa.” Although that isn’t to say that there isn’t still work to be done. “I see how rappers coming from the other side of the bridge, just like me, have gone from having so many doors closed on us to create our own space. Now, we’re being recognised and involved, but I still think we need more appreciation, mainly financially speaking. There are a lot of white people that are inspired by what we do and earn more than us. I don’t think it’s a fair exchange.”

Peroli

“São Paulo is chaotic, but that word should be read as a positive. There’s so much beauty here that, sometimes, it’s possible to find peace in the chaos.”

Though Peroli had a deep passion for music long before she moved to São Paulo with her family in 2011, it took her a little while to pluck up the courage and pursue it as a career path. “It was never my focus,” the 28-year old grime DJ and cultural connector says. “Having a day job was what I imagined would guarantee my stability in the long term.” But after a few years spent in the city, she realised that she could potentially follow her dreams of pursuing a DJing career – and since taking that leap, she’s forged a reputation as a trailblazer for Brazil’s grime scene both within the country and abroad. As well as parties like Batekoo and Perifa no Toque – the platform she founded to “create a safe space for the Black and peripheral communities in São Paulo” – she’s also made regular appearances on Rinse FM and NTS Radio, playing sets that fuse UK influences like AJ Tracey with afrobeats and baile funk. “It’s always tricky when I have to explain to someone what I play, as I don’t see myself in a box,” she says. “Even when I’m DJing at a grime party, it will never be a 100% one-genre set.” Like all of the artists featured here, it’s a musical approach that echoes the fundamentally eclectic spirit of the city she calls home. “São Paulo is chaotic, but that word should be read as a positive,” she says. “There’s so much beauty here that, sometimes, it’s possible to find peace in the chaos.”

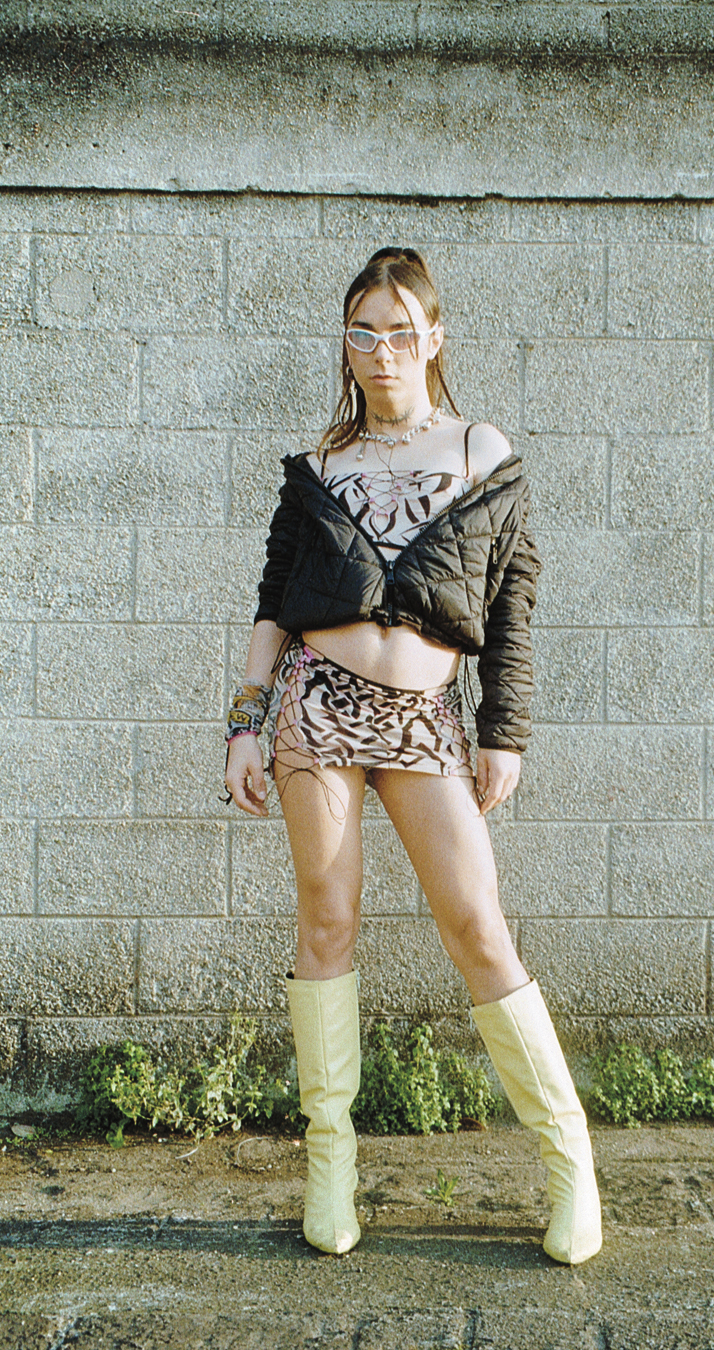

Delcu

“The people in the scene I’m part of are very open to experimentation, to the new, to provocation, and dualities.”

For a testament to Mamba Negra’s influence in shaping São Paulo’s electronic music culture, look no further than Delcu. Back in 2016, when the 28-year-old DJ and producer was already putting on her own nights in the southern Brazilian city of Porto Alegre, a trip to the legendary party was enough to convince her to make the move. “It really opened my head, eyes, and ears in a new way,” she says. It was that decision that set her on the path to becoming one of the most revered presences at parties citywide, including the one that first inspired her relocation. Playing a high energy, joyfully chaotic blur of sounds that span nosebleed techno, funk, and hardstyle remixes of twinkly 00s pop anthems, the throughline of both her sets is what she describes as “kinda cute but kinda violent, sexy bass music. It will probably hit you in the face – but I promise you’ll like it!” Her experimental flair is at least in part owed to the receptivity of the São Paulo crowd to off-kilter sounds. “The people in the scene I’m part of are very open to experimentation, to the new, to provocation, to dualities, whether visually or sonically,” she says. “One of the coolest things I’ve seen happen is the fusion of musical genres. Techno, house, and club music parties are finally not just that anymore, and electronic music styles more popular in Brazil such as funk have been accessing these spaces, too.”

Badsista

“Only the pressure of a good sound system could translate the depth of the creative minds that grew up in this city.”

If we were to wager that there’s one person in this portfolio that you’re already familiar with, it would be Badsista. Fresh from a European tour this summer that included stops at Dekmantel, Primavera Sound, and Berghain, the São Paulo-born producer and DJ is swiftly becoming a name to know on the global electronic music circuit. Yet it is in their hometown that their sets – irreverent clashes of funk, electro, techno, hip-hop, and much more – make the most sense. Theirs is a sound that “collides with the city – its concrete face, crowded transport, and hellish traffic” – an aural adrenaline shot that brings your pulse up to the city’s speed. Their productions, such as their 2021 album Gueto Elegance, reveal the versatility of their perspective as an auteur, encompassing influences as varied as Brazil’s queen of dancehall, Lei Di Dai, and 90s bass music, rich with “strange timbres, sounds that aren’t always what they seem.” Regardless of what music of theirs you choose to tune into after reading this, there’s only one way to listen to it: “On a good sound system with heavy bass!” Badsista exclaims. “Only the pressure of a good sound system could translate the depth of the creative minds that grew up in this city.”

Mu540

“São Paulo is the kind of place where you either go up or you go back to where you came from!”

If BATEKOO is to be considered one of the most crucial engines of São Paulo’s electronic music scene, then that is at least in part due to Mu540. As a resident DJ at one of the city’s best- loved shindigs – and a regular at other major parties like Mamba Negra – he has earned a reputation as one of the most innovative funk-focussed DJs around. There’s a bolshy roughness to his sets: a feature you can easily attribute to the kind of spirit that’s needed to get by in São Paulo. “São Paulo is a busy city – it never sleeps and people are always in a hurry,” he says. “It’s the kind of place where you either go up or you go back to where you came from!” Still, that intensity is counterposed by the complexity and range of funk that Mu540 regularly exhibits in both his sets and productions, which draw on inspirations as varied as grime and polyphonic Nintendo game soundtracks. It’s an eclecticism that he sees as key in distinguishing São Paulo’s musical identity. “The electronic music that we make here uses funk and other styles from the periferia styles as its main tools,” he says, “but what makes electronic music created in São Paulo distinct, though, is that we always mix external influence with what’s from here.”

Credits

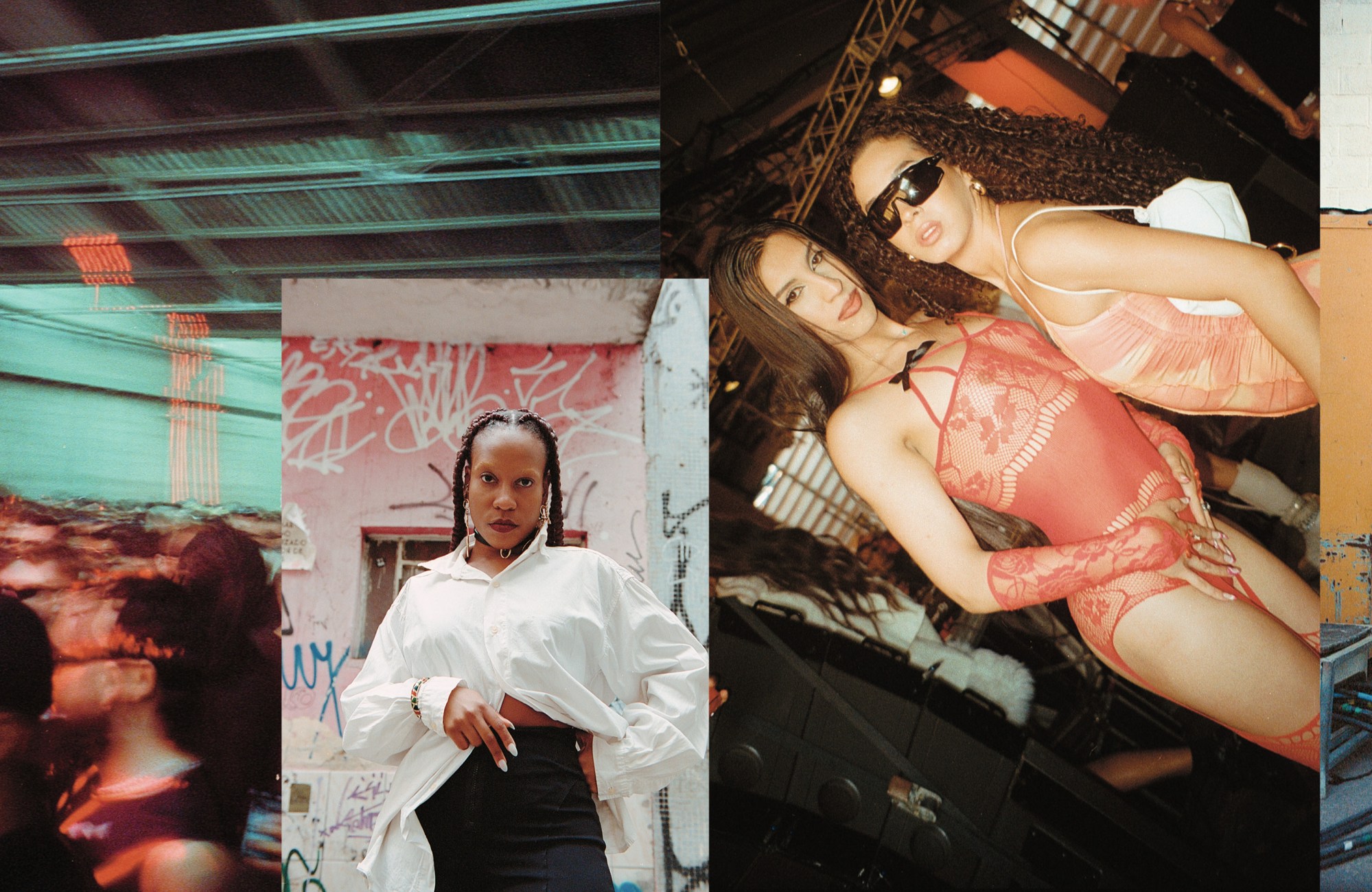

Photography Pedro Pinho

Make up (for Delcu) Eduardo de Castro

Production Fefê Venturini

Shot at Mamba Negra at Fabriketa

Models RHR, Kenya20hz, Maurício Bahia Sacramento, Cashu, Kontronatura, White Prata, DJ Bassan, Febem, Peroli, Delcu, Badsista and Mu540

Special thanks to Igi Lola Ayedun