This story originally appeared in i-D’s The New Worldwi-De Issue, no. 363, Summer 2021. Order your copy here.

Fashion is an industry that fiercely guards its smoke and mirrors, whether that’s the mythology of a smoking tuxedo or the carefully preserved geometry of a mirrored Art Deco staircase. For decades – perhaps even centuries – designers have operated from ivory towers, telescoping subversive influences up to the stratosphere, and as a result, fashion has remained clouded within the upper echelons. The feeling of richer-than-thou exclusivity is perhaps felt most viscerally – for most of the general public, that is – in the clinically lit, casino-like emporiums where prices are always concealed, furniture is never comfortable, and shop assistants look you up and down before deciding whether to help you or not. Boutiques, or brand flagships as they’re now usually known, are mostly designed to feel uninviting. This writer once sliced his leg open on a rusty old sculpture in one and eventually scurried out leaving a trail of blood, no assistance offered. Consider that a bleak analogy for fashion’s extreme, sadomasochistic sense of self-preservation.

In London, you’ll find these boutiques mainly on Old Bond Street, the Mayfair mecca of luxury populated by mink-swathed shoppers. The atmosphere can be frosty, despite the plushness of the interiors and supple fabrics on display. Yet, at number 27, behind a cascading fishnet of hand-embroidered bugs and butterflies is the Alexander McQueen store, which opened its doors in 2019. Its soaring ceilings and honey-toned sculptures by Chilean artist Marcela Correa guide you through the store. It feels warm and inviting, almost like a beautiful mid-century home. But it has a crucial difference to its neighbours. The top floor of the 11,000-square-foot space, usually reserved for private shopping in most luxury boutiques, is instead a space for educational workshops for students, craftspeople and anyone and everyone interested in learning about fabrics, couture techniques and the alchemical processes of McQueen’s design team.

“When we opened the education floor in the Old Bond Street store, we really wanted it to be a space to unlock and demystify the creative process, making fashion more tangible for anyone who wanted to learn about it,” says Sarah Burton, the designer on a mission to dismantle fashion’s terrifying froideur and the hackneyed cliché of cerulean-obsessed Pollyannas. Cheshire-born, Central Saint Martins-educated Sarah has been the guiding force of McQueen since the passing of its founder, Lee, in 2010. But she’s been a part of the team since she was a student herself, joining as an intern. In fact, Lee helped her source fabrics for her final collection, which she briefly left the team to complete before returning as a graduate in 1997. She has remained faithful to McQueen since. “We are vert fortunate to do what we do and I wanted to show emerging creatives what a broad variety of positions are available in the industry,” she continues. “It’s also been a project that the whole team has contributed to – really, we are a community of creatives above anything else.”

In her role, Sarah oversees everything at McQueen: womenswear, menswear, accessories, campaigns, communications, retail. She is the guardian of one of the most precious legacies and archives in fashion history and one that she has helped create for more than half her life. Her vision of fashion is perhaps softer than her predecessor’s, a bit less theatrical, but no less romantic or feminine. During her time as Creative Director, Sarah has made it her calling to champion craftsmanship, whether it’s precision tailoring, hand-woven textiles or ornate embroideries. She often begins each collection by taking her close-knit design team on a field trip to source ideas with their own eyes, instead of copy-and-pasting images onto a mood board. And considering she grew up in Macclesfield, a town in the rural shadow of the Peak District, surrounded by factories and mills that make traditional British textiles, it’s little wonder that she’s utterly devoted to the preservation of handicraft.

When it came to designing the store, however, she decided to do something radical. On the top floor were some original pieces from McQueen’s breathtaking archive, displayed in full regalia, not behind a museum’s glass vitrine. They formed the backdrop to workshops that unleashed the intricate process of their creation for students from across Britain – and anyone else, for that matter. It set the scene for tutorials on cutting, sketching on draping from Sarah and Judy Halil, McQueen’s head of atelier, as well as life-drawing workshops overseen by artist Julie Verhoeven. On one afternoon, a generation of fledgling creatives could learn how to swirl a piece of taffeta into a voluminous rose; on another, how to capture the silhouette of a dress or cut an exquisite jacket.

And though it began as an intimate in-store concept, it has slowly spiralled into a full-on cultural initiative. Soon after, McQueen began donating its surplus fabrics to students in fashion colleges across the UK – much like Lee did for Sarah – as a way of reducing waste and supporting a new generation’s upcycled fashion. “It’s about supporting young people who are vital in order to keep our industry alive,” Sarah explains. “It’s even harder today, and at a time when we all feel precious resources must be properly used.” And when she and her team visited Wales for a research trip for the AW20 collection, they came across a project called It’s called Ffasiwn, which offers free creative workshops for children across the South Wales Valleys led by Charlotte James and Clementine Schneidermann and chronicles it through documentary photography. They worked together with them on a photoshoot featuring the kids wearing custom AW20 McQueen looks, scaled down to smaller sizes, as well as a programme of workshops on casting, creative writing, embroidery, styling and photography during which they could use McQueen’s materials, customise their pieces and be photographed alongside their contemporaries.

This isn’t some kind of marketing initiative designed to win over Gen Z customers, or indoctrinate brand loyalty from an early age. It’s inclusivity in its purest, simplest form. If the blockbuster exhibitions on McQueen demonstrate anything, it’s that even the most sceptical fashionphobes are in awe of the brand and its incredible archive. In fact, it sometimes feels as if it were a cultural institution in itself. “One of the most inspiring things about that project in Wales was to see how personal the young people involved made things and how creative they were,” Sarah says. “I’m really interested in engaging with creatives of a younger age, who don’t necessarily have preconceived ideas that they want to be designers – or even work in fashion – and giving them the means to express themselves.”

For many of them, a career in fashion may seem far off, but the idea of planting the seeds of creativity and self-expression is powerful nonetheless. “The idea is that we’re opening up that landscape to them, explaining that there are fashion photographers, stylists, set designers – that there are big teams of creatives that come together to form every image, every show,” she adds. “It goes back to the idea of unlocking what we do here and ensuring that the younger generation are able to see what might be possible for them in the future.”

Then Covid hit. Bond Street, and McQueen’s usually clattering ateliers, closed during lockdown. As the world logged on to a plugged-in digital reality, so did McQueen’s education initiative – and perhaps it was more needed than ever, as kids were stuck at home, unable to experiment with paints and Pritt Sticks in the art classes at school. McQueen began hosting virtual tutorials, setting a brief and encouraging people around the world to submit photos of their work. These included a 3D rendering of flowers as clothes (an idea first explored in McQueen’s SS07 ‘Sarabande’ collection), a YouTube tutorial on how to stitch together a simple bee embroidery (a motif from SS13) or a masterclass in creating patchworks from found objects and fabrics from around the home (inspired by AW20’s crafty intarsia). It was a way for people to engage with lockdown hobby-craft at a couture level.

“We wanted to encourage people to work with their hands during this time and provide a creative outlet, supporting them to learn how to drape, print, sew and embroider at home,” Sarah explains. “It wasn’t solely aimed at students. It was also an initiative to help people get through the current circumstances, to enjoy the creative expression that we ourselves are privileged enough to benefit from.”

An arts education is increasingly a privilege reserved for the few, rather than a rite of passage for anyone with big dreams and few resources – someone like Lee McQueen, for instance, who went from a tailoring apprentice to a bursary student at Central Saint Martins and was on the dole for much of his early career. In the last year alone, severe cuts to arts funding have meant that a generation of young people, right from elementary school to art college, have had far fewer opportunities to pursue creative studies. A BBC survey showed nine out of 10 secondary schools had cut back on time, staff or facilities in at least one creative art subject in the last five years. A further study by Tate showed that if the decline in secondary school arts provision continues, many children may have little opportunity to take arts subjects by the time they turn 11 years old.

To put it bluntly, as the Cultural Learning Alliance does, there has been a 35 per cent decline in young people in Britain taking arts subjects at GCSE level in the last decade. Not to mention the impossible costs of studying at fashion schools at higher education. During lockdown, it’s only gotten worse, with lower-income children studying from home suffering the most. In Tower Hamlets, minority communities are most affected by funding cuts and Arts-related subjects are not even on the curriculum at several schools, further stacking the odds against kids eager to progress into the creative sector. McQueen, for their part, supported the A-Team Arts in the borough where it was based when it first launched, to provide half-term workshops for the young people learning there. Members of the studio team hosted classes covering print, draping and embroidery, teaching the young creatives one-on-one throughout the course of the week.

However, the government’s relentless cuts to arts funding and education are not just austere, they are short-sighted considering creative jobs are the least vulnerable to automation. After all, how could a robot ever achieve the emotive beauty of a hand-illustrated sketch, reconfigured as a paper maquette, and transformed into a dress made from Irish linen grown from organic flax and hand-crafted in Northern Ireland on a female-owned farm? That dress, by the way, was a result of one of McQueen’s workshops in which students’ sketches evolved into a figuratively embroidered dress worn by the late Stella Tennant in the house’s SS20 catwalk show. It was an instance of when inspiration was symbiotic, McQueen’s design team finding theirs in a project about inspiring students. All of the students were credited by name for their artwork in the show notes placed on every seat at the show in Paris, as were members of staff from across the business – publicists, accountants, interns – who Sarah encouraged to hand-stitch the embroidery at McQueen HQ.

“When times are so much more difficult for young creative people, taking action to share our resources and open eyes to opportunities has become a central in-house commitment,” says Sarah. And she means it – this is a woman who couldn’t be further from corporate jargon and ‘design by marketing’. Often, backstage at her shows, she still has her pin cushions strapped on her wrists, and her hands-on approach has filtered through the culture of the global business she presides over.

“We really work as a team at McQueen. It’s not about a single person but more about a community. Doors are always open between us and the sharing of ideas is vital,” she adds. “We strive to create an environment where people aren’t afraid to give ideas and to break down boundaries between us all, creating a very inclusive way of working.” McQueen is a fashion house that is a home to creativity. “There are many people who have worked for the company for years – even since Lee was here – and we really do operate like a family,” concludes Sarah. Now, thanks to her, a new generation of creatives and craftspeople are part of it, too.

Credits

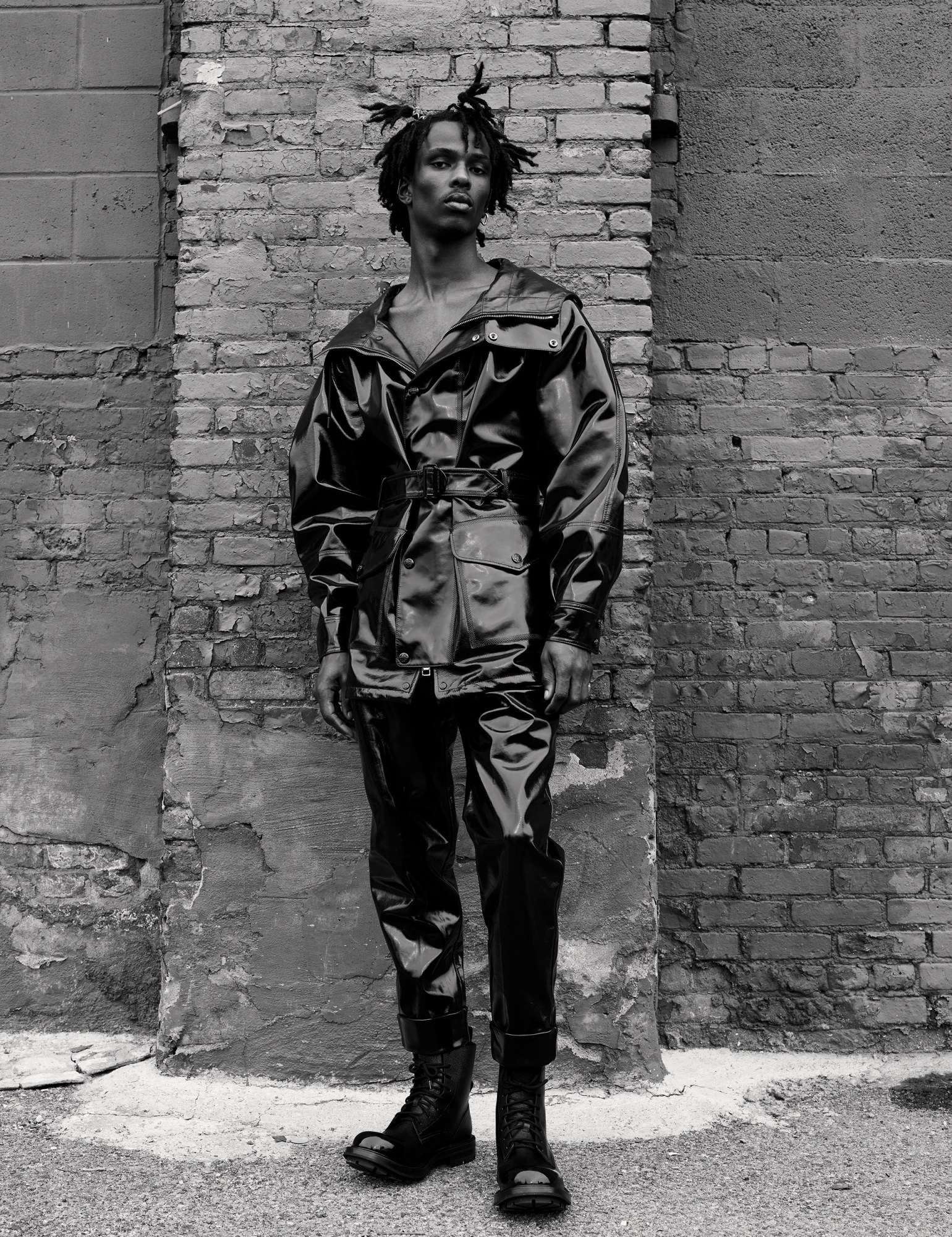

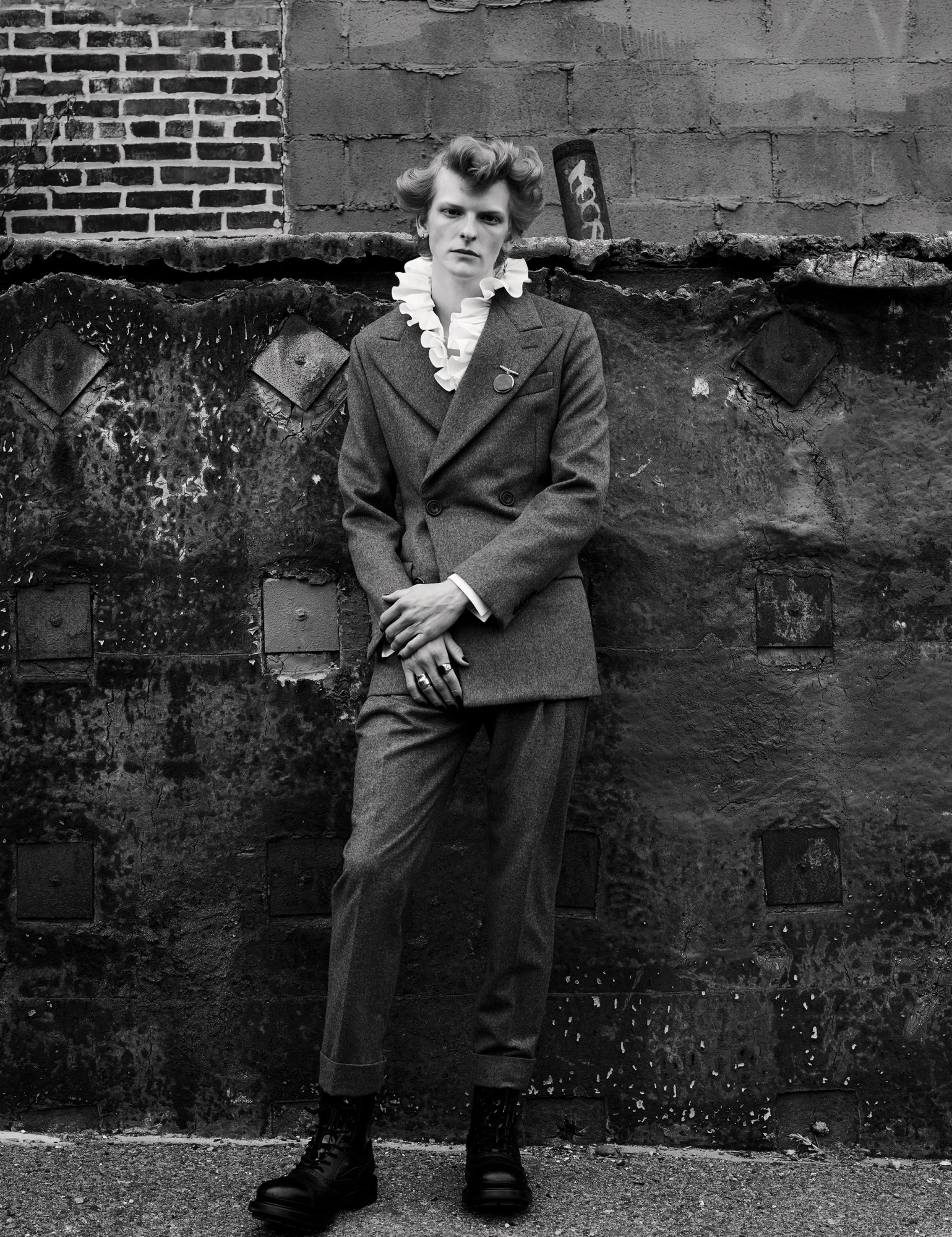

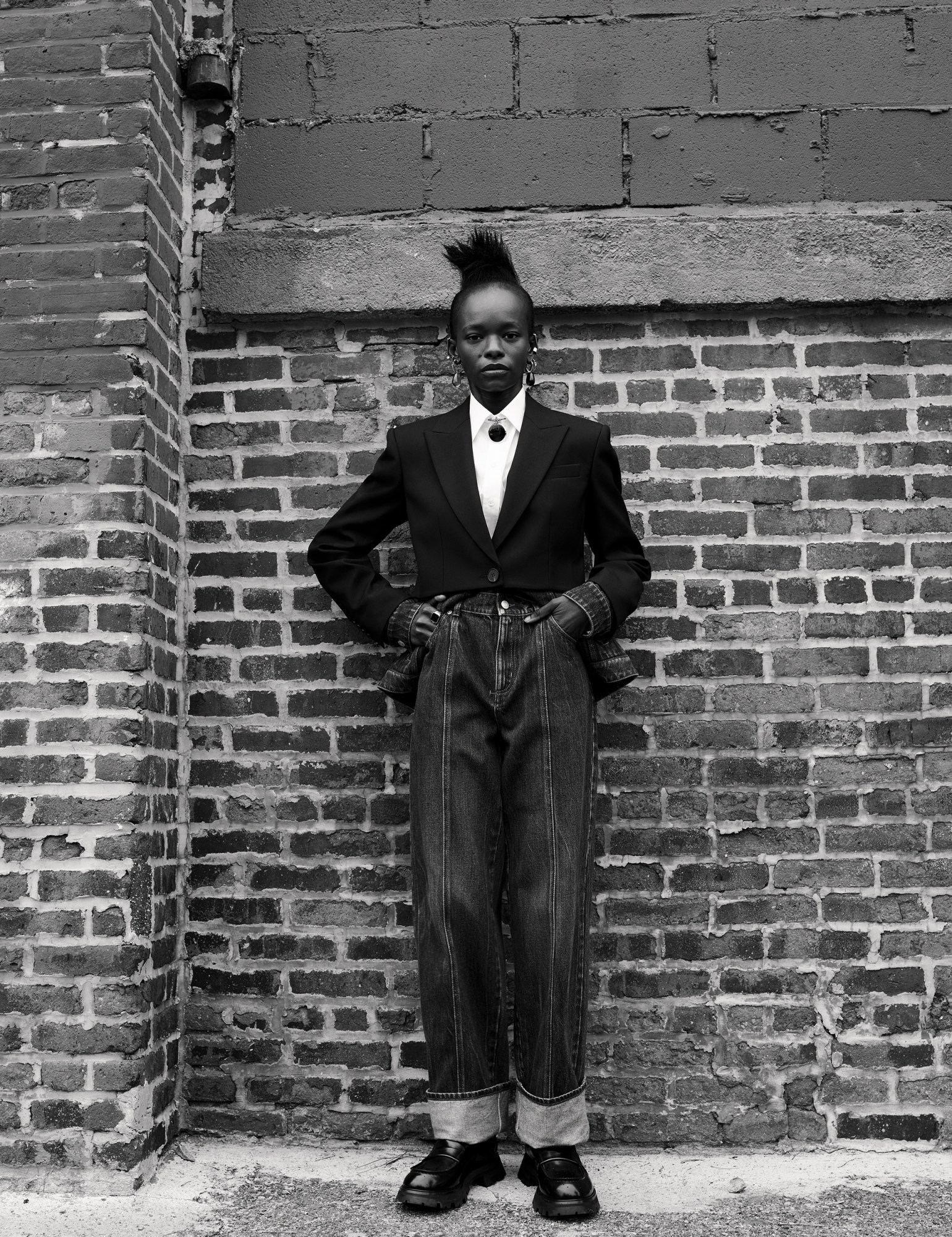

Photography Amy Troost

Styling Malina Gilchrist

Hair Esther Langham at Art + Commerce.

Make-up Fara Homidi at Together using Chanel Beauty.

Nail technician Michina Koide at Art Department using Chanel Le Vernis.

Photography assistance Karen Goss and Darren Hall.

Digital operator Alonzo Maciel.

Styling assistance Sidney Munch and Adam Van Osdol.

Hair assistance Ginger Ryan and Lauren Berrones.

Make-up assistance Miki Ishikura.

Production Cat Lewis at MAP.

On-set production Alex Royals.

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING.

Casting assistance Alexandra Antonova.

Models Emily Krause at Kollektiv. Sara Skinner at Heroes. Somali Findlay at IMG. Parker Brownat Next. Hawah Jabbie at System Agency. David Prost at Midland Agency. Tianna St. Louis and Dien Kim at New York Models.