In the opening scene of Savanah Leaf’s directorial debut Earth Mama, an unnamed woman stands tall in the middle of a dimly lit classroom. She addresses you, speaking directly to the camera. “You can hold my hand,” she says. “You can look back from a distance. You still won’t feel what I feel. You still won’t look at it from my point of view. When everybody got an opinion, judgment, like they God.” It’s here that the story begins.

Viewers soon piece together that the woman is a mother whose children have been taken from her and placed into the foster care system. While she’s not a main character or pivotal to the narrative arc, the opening scene is the film’s thesis: The U.S. separates Black mothers from their children, depriving them of basic humanity, then forces them through a violent bureaucracy that intentionally leaves little opportunity for the family’s success.

“I wanted to show an honest portrayal of a woman going through a system that is set out against her,” 29-year-old Savanah tells me via Zoom from the A24 offices in New York. “All she wants to do is mother, yet that’s being taken away from her.” And throughout the film, viewers see just that. Earth Mama follows Gia — played by the quiet yet powerful Tia Nomore — a pregnant single mother of two children who have been removed from her custody after she experiences substance use disorder.

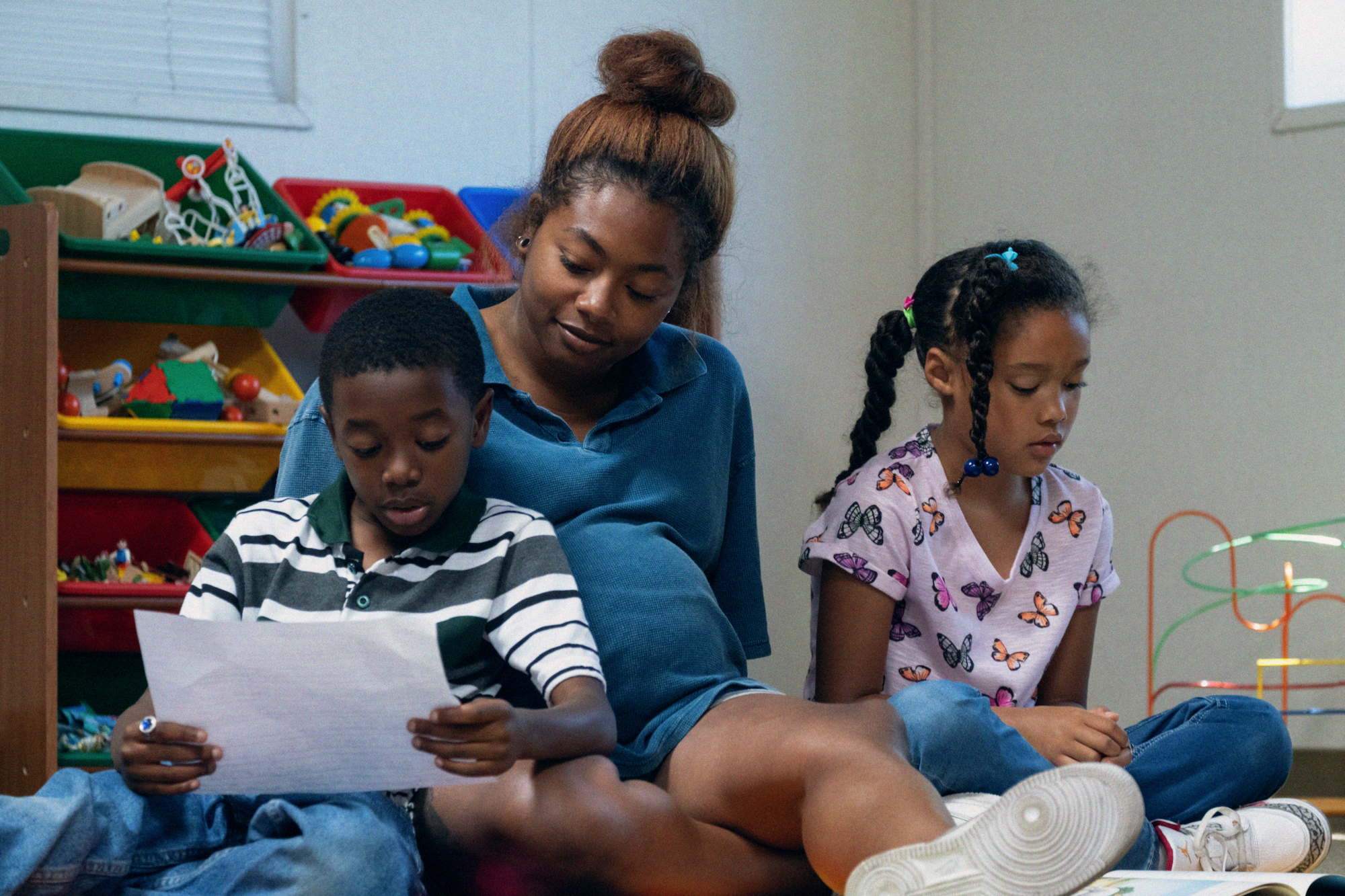

From her first moments in the film, it’s clear that Gia is doing everything possible to reunite with her children, who she is only allowed to see once per week, supervised, in the youth playroom of a bleak government building. She’s now sober, but struggles financially. (In some scenes, she steals diapers from a playground stroller and asks for hundred-dollar advances from work.) To make matters worse, Gia is only employed part-time at her photography studio job. All of the required classes and appointments she must attend in order to qualify for regaining custody make it impossible for her to work more hours.

Accounting for how much she is struggling and how pained her children are by their separation, Gia considers giving her unborn child up for open adoption. While fictional, this scenario is inspired by a close reality to Savanah. Born in London and raised in California, the former Olympian — she represented the UK in volleyball in 2012 — gained a sister during high school when her family adopted a newborn. Earth Mama is an expansion of Savanah’s documentary short film, The Heart Still Hums, that she made alongside Bones and All star Taylor Russell. Savanah calls the short, which follows the lives of five mothers fighting for their children through homelessness, addiction, and generational neglect, “emotional research” for her feature film and, for life.

“Making a documentary feature on this story can quickly become unethical,” Savanah says, noting that she didn’t want to pressure women to publicise personal stories that might impact future custody arrangements. “Fictionalising it allowed me to tell details that people don’t want to share,” Savanah says. “You can go deeper and create a film where, in a way, it can be even more honest than a documentary, saying things people are too afraid to say, creating questions with the audience that I couldn’t have otherwise.” Grounded in realism, the film doubly portrays the agonising yet deliberate authorities that drive families apart.

A strength of Earth Mama is its cinematography, shot by Jody Lee Lipes on 16-millimetre film. Long, close contemplative shots show Gia observing nature — Lynchian California Redwoods blowing in the wind, glistening blush sunsets over the Pacific. “I wanted to show her inner life without having a conversation between people in the film,” Savanah says. These scenes are “more of a feeling,” often set in dark blue, pink and moody lavender hues, accompanied by ambient, soft jazz that deepens and crescendos, immersing you in the emotional truth of the moment without telling you how to feel. The film was scored by Kelsey Lu, who invited musicians to improvise over the movie’s visuals, creating the composition’s natural fluidity and instinct.

“I was unsure if the audience would resonate with the style, since it’s not typical of American cinema. From a visual, aesthetic standpoint, our film lingers, almost like a hum,” Savanah says. This technique is also what allows the actors to shine. Tia’s performance is admirable for her ability to stand at the very centre of Earth Mama, as she’s in almost every scene. She’s supported by seasoned actors like Erika Alexander, who plays Miss Carmen, a social worker shepherding Gia through the broken system, as well as those making their acting debut, like rapper and singer Doechii, who plays Trina, Gia’s also-pregnant best friend.

One of the film’s central social tensions is the friction that the potential adoption causes between Gia and Trina, who doesn’t think it’s moral for Gia to give up her child. In one of the more memorable monologues, Trina says to Gia, “There’s a lot of people expecting us to fail. My whole life I had shit taken away from me. They try to take our culture. They try to take our homes. They try to take our freedom. And you know they’ll try to take our babies, too… it’s our God-given right to have our kids.” Ultimately, Doechii’s character is an essential one, acting as a voice for the rightful anger at the limited alternatives to adoption that are available to women like her and Gia.

Musician and Euphoria star Dominic Fike also has a small role as Gia’s co-worker at the photo studio. Gia’s employment is a fascinating aspect of the film, serving both an artistic and interpretive purpose. Savanah capitalises on the whimsical nature of the photography setup, filling it with a variety of backdrops that all fall effortlessly into the film’s colour scheme. The usual customers are families and lovers, placing Gia close to her dream of unity that’s so out of reach, Savanah explains. Gia also assembles happy scenes for the families, dragging a better-suited background into frame, positioning timid hands, fluffing the skirt of a prom dress — an assertion of environmental control where she can, despite lacking it elsewhere.

In the studio, we also see that the best supporting cast members are not always the ones who contribute to the film’s narrative propulsion. A group of background actors whose roles were to harass Gia outside her apartment — originally present for comedic relief — ended up playing a more experimental purpose that was not in the original script. Meeting the men on set, Savanah learned that one of them was incarcerated for 10 years, and that others had difficult upbringings in the foster care system. “They felt like older versions of Trey, Gia’s child,” Savanah says. Thus, she gave the actors their own artistic interlude, framing it as if they shared their stories with Gia at the studio, detailing how foster care and separation from their mothers impacted their lives as Black men.

Despite all the stunning visuals and creative excellence, the message Savanah wants to send through Earth Mama is not one of trauma porn. “For me, this was about hero-ing this community in a way that is observant, and doesn’t glamorise the sensation of pain and suffering,” she says. The final note of the film centres Black mothers. “I think of Black women as being the centre of the universe. They are the mother of all mothers. They have been mothering everybody,” Savanah says.

The final line of the film features yet another unnamed mother from Gia’s classes, recounting her experience in “the system” from childhood to adulthood. “No one was there to protect me,” she tells the camera, as the credits begin to roll.

Credits

Stills courtesy of NBC Universal.