This story was originally published by i-D UK.

When many people think of Black Power, the first image that comes to mind is often a male Black Panther Party member — in a black beret, gun in hand — or even Beyoncé’s infamous 2016 Super Bowl performance, flanked by her backing dancers, fists raised in the Black Power salute; or maybe the #BlackLivesMatter protests of recent years. While these are all vital elements in the decades-long Civil Rights fight, it was African American women of the 1960s and 70s that developed the backbone of this movement (by the early 1970s the Black Panther Party was two-thirds female); many of them were art activists, and their work is being shown in a major new show opening this week in London at the Tate Modern.

“My art became my weapon. It became my visual protest about what was happening,” says Betye Saar, one of the women featured in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. Saar, born in 1926, is credited with establishing the black women’s movement in America in the 1970s. Her work draws on emblems and stereotypes of African-American culture, bringing together found and sacred objects from her childhood to create colorful, eclectic sculptures that tell the story of the African-American experience.

One of these works is The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972) — on show in Soul of a Nation — a mixed media piece exploring the stereotype of the reductive ‘black mammy’ figure in popular culture, as well as the radical means by which people were fighting for their civil rights. “She became my warrior to fight racism,” says Saar of the piece. “I was a young mother with three children. That was my job. I was emotionally affected by the violence in the South on television. The conflict between the civil rights protestors and the Southerners, the police beatings, the dogs, the fire hoses attacking peaceful marchers.

“I was extremely angry. I did not want my children to see what was on television. The murder of Martin Luther King Jr. was very also very emotionally traumatic for me. I was so sad.”

She translated this rage and sadness into a force for change with her art. Angela Davis — political activist, academic, author, and leader of the Communist Party USA — once described Saar’s work Aunt Jemima as the catalyst for the movement and an inspiration to a generation of black female artists. Saar cites other works of hers such as Two Darkey Songs (1974), Is Jim Crow Really Dead? (1972), Black Crows in the White Section Only (1972), and De Ol’ Folks at Home (1974) as being particularly important in her fight against oppression. “These works truly expressed my responses to racism and the violence that occurred at that time,” she says.

And Saar believes this fight can’t stop with the work of her and her peers, and talks about the importance of black female artists like her who are still working today, such as Sue Irons (now Senga Nengudi) and Suzanne Jackson. “Many black artists made art to protest injustice and fight racism. Many things have changed, but racism is still here,” she says.

Another woman whose work features in Soul of a Nation is Jae Jarrell — born in 1935 — who used radical fashion and textiles to push the message of AfriCOBRA, the African-American artist collective she co-founded in 1968.

“Clothes are like a flag. You should wear your revolution,” says Jarrell, who grew up in Cleveland, Ohio surrounded by the tailoring of her parents. She had a respect for the craft instilled in her from a young age: her mother — a gifted tailor who outfitted all the Harvard professors — would take her to thrift stores just to get up close to various garments and point out the details. “She would fold down a collar to show me the stitching,” remembers Jae. “And she would always say, ‘Just look at that workmanship.'”

Later on Jae found herself in Chicago at art school, where she got a grounding in all art practice (ceramics, fabrics, painting, sculpture) and held her first fashion show “Fashion Safari’, which was inspired by the decolonization of various African countries occurring at the time. She went on to found AfriCOBRA with her painter husband, Wadsworth Jarrell, and three other black artists, which included painter, printmaker, and filmmaker Barbara Jones-Hogu.

“We had a temperament of work hard and play hard, we were already on a path,” remembers Jarrell of the early days of the Chicago collective. We knew we weren’t going to be derailed. We wanted to create an organization for power for our people.” Rather than bringing about change through political revolt, AfriCOBRA aimed to use a black identity and worldview to foster solidarity and self-confidence throughout the African diaspora. It was supposed to be a revolution of the mind, body, and spirit and the bright, bold, uplifting art they created reflects this.

Jarrell herself made unique garments, using the body as a vessel for revolution. She incorporated diverse elements like brick walls, graffiti, colorful bandoliers, jazz, Scrabble, and African shields. This can be seen in works like Revolutionary Suit (1968), with its jarringly cheerful bright yellow ammo belt of fake bullets, and Brothers Surrounding Sis, its skirt emblazoned with brightly colored figures defiantly linking arms in solidarity. Both pieces are featured in Soul of a Nation.

AfriCOBRA’s first ever exhibition was called The Black Family, held in 1969 at Jae and her husband’s studio on 61st Street in the Chicago neighborhood of Woodlawn. It was a response to the stereotype of the dysfunctional black family presented in 1965’s Moynihan Report: a widely-criticized study which argued that the rise in American black single-mother families was caused by “ghetto culture.” For Jarrell, family was (and is) especially central to her life and work. She believes that activism, art, and family are not mutually exclusive. “You should wrap your kids up up and take them with you,” she smiles. “Just like packing your lunch and going to work.”

She brought up three children in AfriCOBRA, and sees it as part of the positive message she and her collective wanted to push. “We weren’t really interested in shows, we were interested in leading our people in a beautiful manner,” she says. “Our stuff doesn’t get old because we are not narrow — we’re big. With our work you feel like you’re in a cathedral.”

Of course, Jarrell and Saar are far from the only female artists being shown in Soul of a Nation.

Zoe Whitley, one of the exhibition’s curators, set out with the specific aim of ensuring a gender balance was struck. “I think the show is timely and a long time coming,” she says. “These artists shaped art history in the 20th century, not only in a US context, and are under-recognized. We think we know what we mean when we say “20th century art” and it’s Andy Warhol, not Bettye Saar. We’ve worked very diligently to ensure the exhibition is a corrective in terms of not privileging male voices.”

Zoe cites Alma Thomas — who was, in 1972, the first African American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art — and Faith Ringgold as other particularly inspiring female artists featuring in Soul of a Nation. Ringgold’s American People Series #20 Die (1967) is an unflinching and bloody look at racial tensions, told through the eyes of women both black and white.

Born in Harlem in 1930, Ringgold produced posters for the Black Panther party (which can be seen at Tate Modern) and when the Whitney Museum organised a show about 1930s American sculpture that included no black artists, she mobilized demonstrations against the exclusion of black and female artists. She also co-founded Where We At, a group for African-American female artists, in 1971.

A piece by Elizabeth Catlett — the grandchild of freed slaves — striking wooden sculpture, Black Unity (1968), is also in Soul of a Nation, one surface depicting the faces of two African women side-by-side, the other a huge raised fist — an enduring symbol of Black Power to this day.

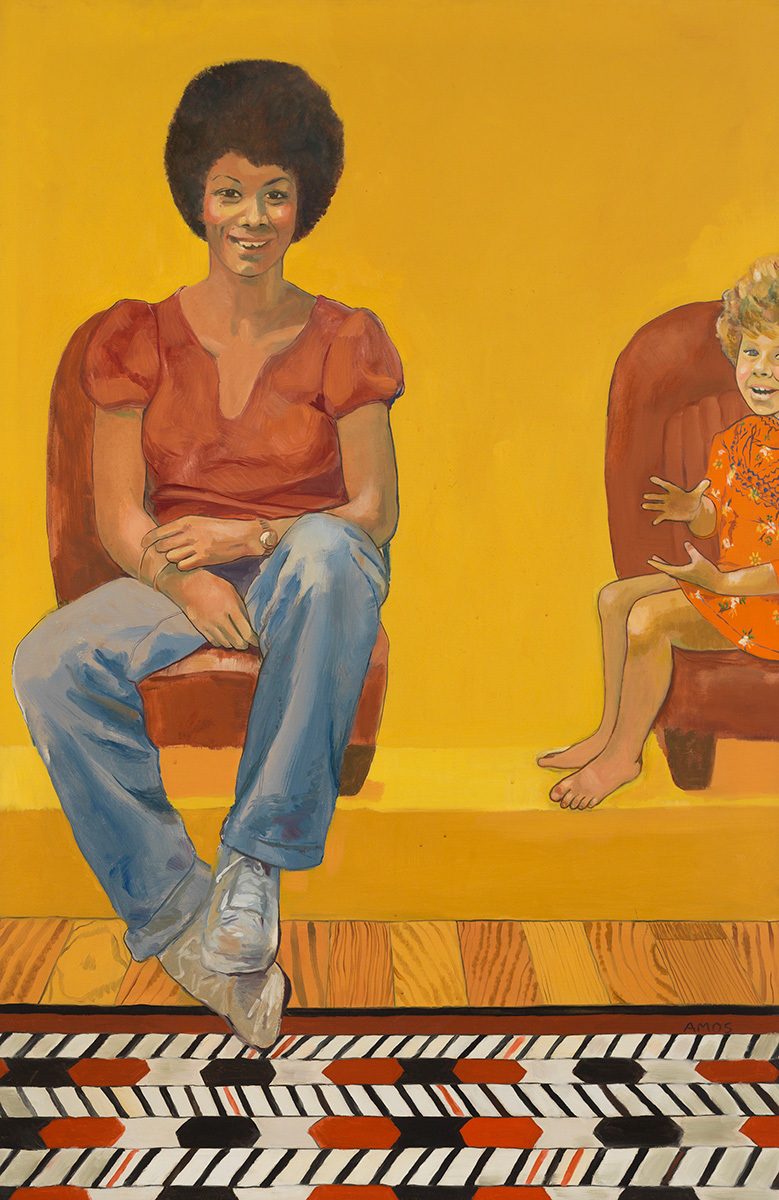

Another artist in the show is Emma Amos, the only female member of the Spiral collective, who questioned how African-American artists could respond to racism and represent their own communities. Amos was also involved in Fantastic Women in the Arts: a group who explored the artwork and writings of female artists, and on how the feminist revolution of the 1960s and 1970s seemed to be failing black Americans. One of her pieces, featured in Soul of a Nation, is painting Eva the Babysitter (1973): expressing how, on a practical level for a female artist, a babysitter is a vital part of maintaining studio practice.

For curator Zoe Whitley, what is most vital about the female artists of the Black Power movement is that — like any group drawn together for the sake of a large exhibition — they all express compelling points of view that are often incompatible. “They are all putting forward different proposals about what art is, who it should reach, and how it should be shown,” she says. “I want visitors to take away how complex ‘black art’ is and have a deeper understanding of the range of practices in what we think of as ‘American art.'”

Despite these differences the women of this art movement seem to agree on one thing: they’re black and proud.

Credits

Text Emma Finamore