Since Raf Simons parted ways with Dior last season due to the pressures of the fashion cycle, the debate about our overworked fashion system has raved through the industry to the point that it had to resonate in the collections themselves. In London, Christopher Kane commented on the throwaway culture of fashion—a huge part of the problem, seeing how high fashion is now expected to keep up with the high street. In Milan, who else than Miuccia Prada could pick up the torch? Shown in the same set as her men’s collection in January, meant to represent a medieval square with all the public celebrations — and executions — hosted there, it was a public spectacle: a collection for the people, and something we could all relate to. It had all the naval elements of the men’s collections, but this time Prada didn’t speak about the sea as a metaphor for migration and warfare — i.e. a reflection of what’s going on in Europe right now — but rather “the history of women,” as she said. “This is different moments—different dramas, different happiness. She’s beautiful when she’s unhappy and she’s beautiful when she’s vulnerable. Because we need to understand where we are now.”

And so, those naval elements became symbols of taking charge. “It’s the beauty of regality and empowerment. Do you make yourself beautiful because you want to be in command?” Mrs Prada asked, typically rhetorical. She said each piece in the collection, from the objectified femininity of a corset to the more empowered femininity of opulent brocade coats, was a symbol of “some kind of woman.” But there was much more to that thought process. In a fashion industry dominated not just by seasonal collections but pre-seasonal collections, too, and the notion that women’s wardrobes now change four times a year, she was making a case for the power of the individual—and individuality itself. The very reason the industry is so hot on changing the system right now is because we’re all so painfully aware that the fashion cycle represents an illusion. No one really changes wardrobes that much, and if they did what would that say about their sense of identity? (That’s rhetorical, too.) Prada put the months of the French Revolution calendar on garments: Vendémiaire, Brumaire, Frimaire etc. All female names, she found the relation of women to nature and time poetic, and asked Christophe Chemin — who also did artwork for the men’s collection — to illustrate the seasons in print.

Of course, the female calendar theme spoke volumes of Prada’s intents. Women don’t change every season—fashion does. Displayed on that public square for everyone to see, her call for us to slow down was both powerful and empowering. For his second collection for Emilio Pucci, Massimo Giorgetti reminded us we were in Milan with an Italian wardrobe for ladies who ski. This was the fabulous, wealthy socialite segment, ciao’ing as they pass each other on the slopes in all their Pucci glory. Astutely, he’d asked himself if those people actually still exist, which is another problem in the big discussion of the fashion system. Who are these elusive segments of people we’re aiming collections at? In that sense Giorgetti’s sophomore effort was on point, and a clear statement as to his intentions for the house. His Pucci will be Italian in the swanky sense, with all the puffa coats with mountain prints and geometry knitwear that entails, and you only need to walk down Via Montenapoleone here in Milan to see that there’s definitely a market for that.

Karl Lagerfeld loves to make waves, but when he does it at Fendi it’s always rather more subtle than at Chanel. At Silvia Venturini Fendi’s fur house he’s arty and crafty and a little bit mysterious, but Lagerfeld is as much of a thinker as Prada. The waves he made on the second day of shows in Milan were of the literal kind: ruffles, illustrated eminently in the sketches he’d put on every seat as a kind of fluid garment on the body, almost like air was blowing from within creating those waves. Apparently it had something to do with Einstein’s theory of gravitational waves and time travel, but there are limits to the educational value show coverage should subject you — and this writer — to so let’s leave it at time. Yes, there it was again: the recurring theme of time, which only last week, Silvia Venturini Fendi told yours truly was one of the greatest luxuries in life. Lagerfeld’s collection for Fendi wasn’t a comment on the fashion cycle, however much it would fit the angle of this story, but at least an echo of a topic that fills our minds more that anything these days. If there were ever a house to be the poster brand for slowing down the cycle and chilling out on the over-consumption, it would be fashion’s artisanal epicenter of Fendi whose furs and bags will last you a lifetime.

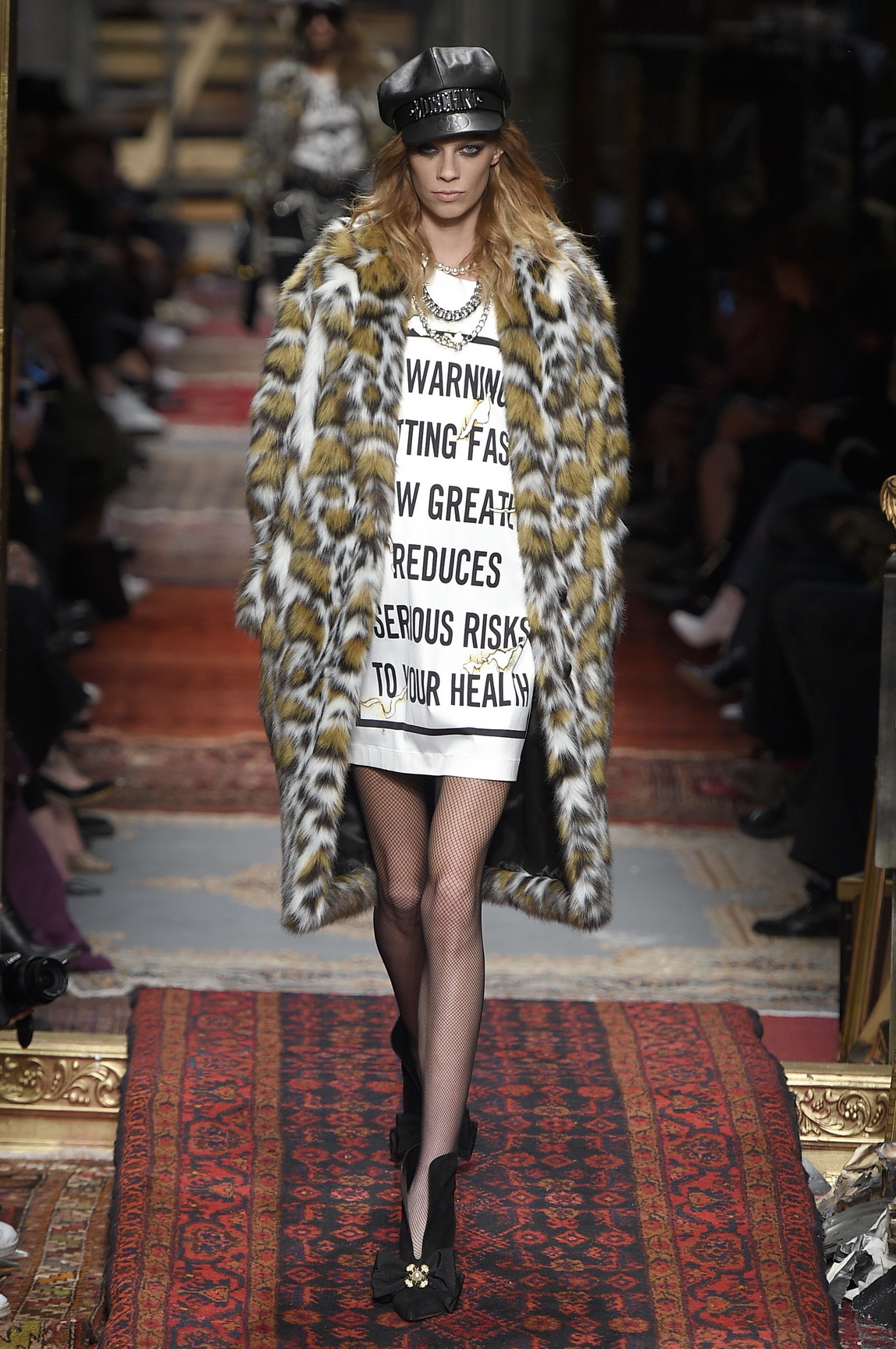

You couldn’t have made a stronger point about the fashion system than the one Jeremy Scott made at Moschino where guests were met by a disheveled palatial interior. Chandeliers had fallen to the floor, Victorian salon sofas were knocked over, and there were pieces of chairs everywhere. Inspired by the Bonfire of the Vanities — the 1497 mass-burning in Florence of items representing ungodly vanity — Scott made a brilliantly meta statement about the industry’s double-standard when it comes to said over-consumption and the whole debate about the fashion cycle. We’re all aware that too much is enough, but we still want more. And so, his new phone cover was a pack of cigarettes with the words “Fashion kills” on it, and his decidedly high-glam collection of biker and formalwear (like something out of Dynasty) came with burn holes and smoke coming out of garments, like a grand statement about society’s addiction to fashion. It certainly put things into perspective. How does the industry find the right balance between reasonable consumption and the big business that’s necessary for it to survive? Only time will tell.

Credits

Text Anders Christian Madsen

Photography Mitchell Sams