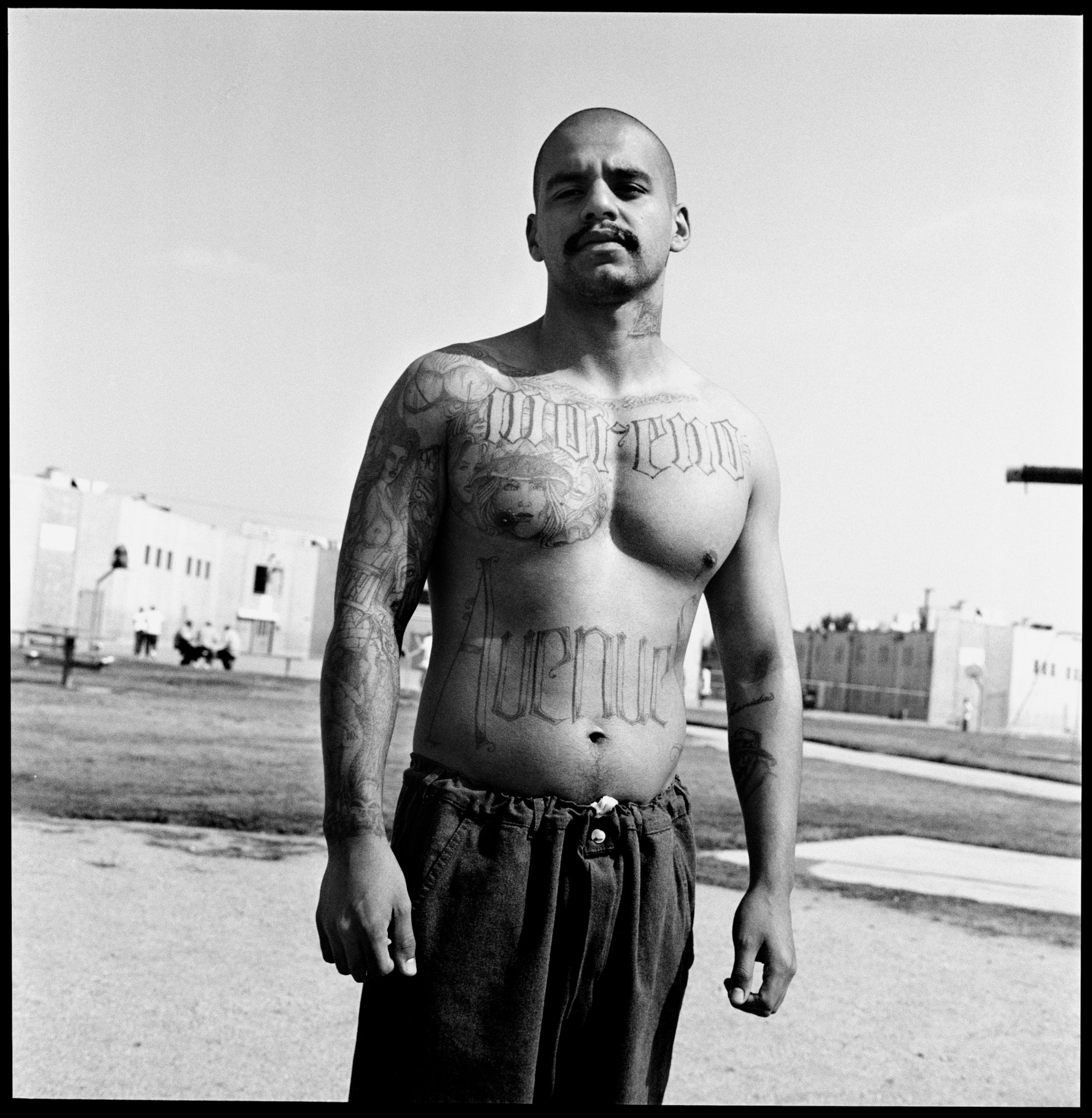

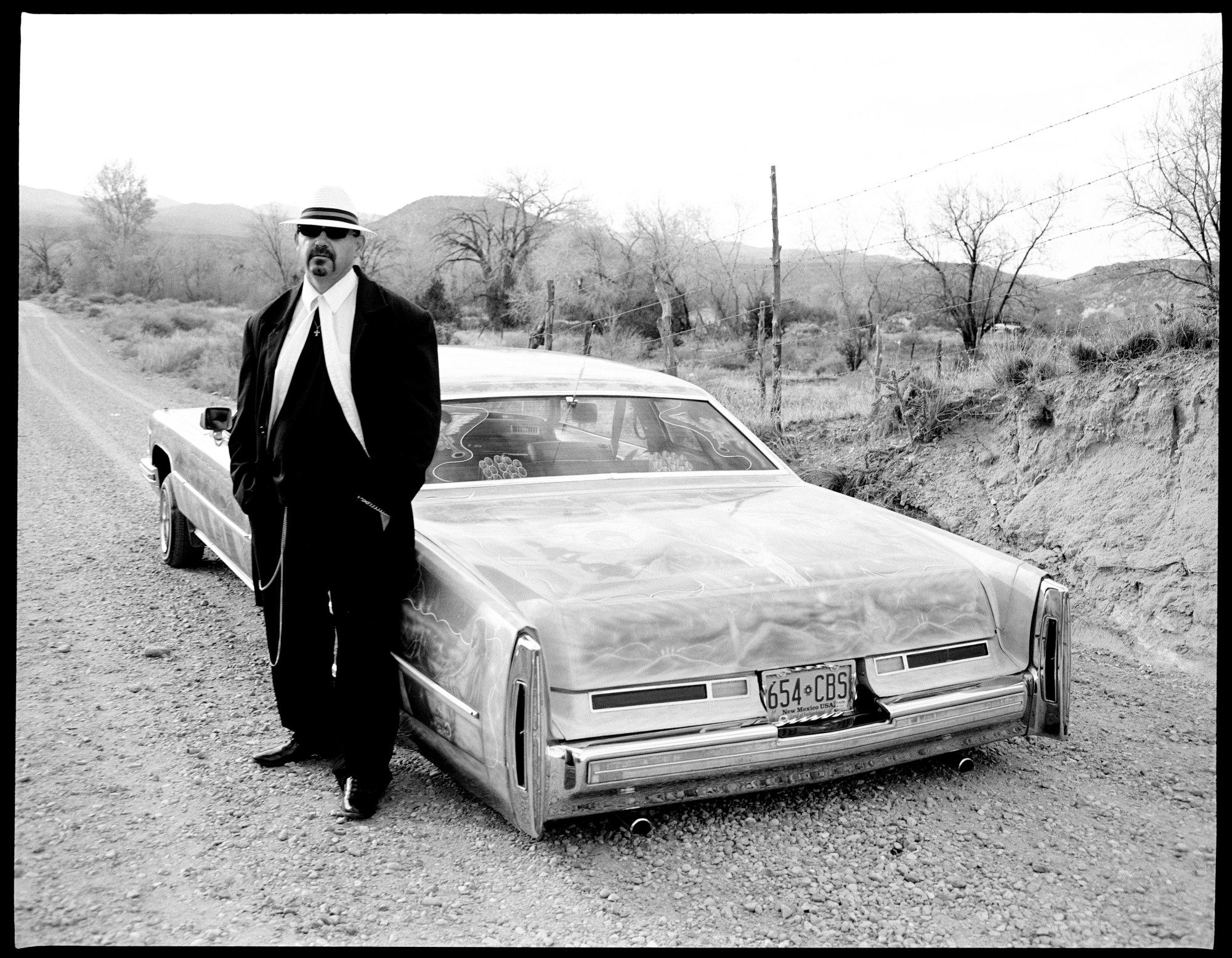

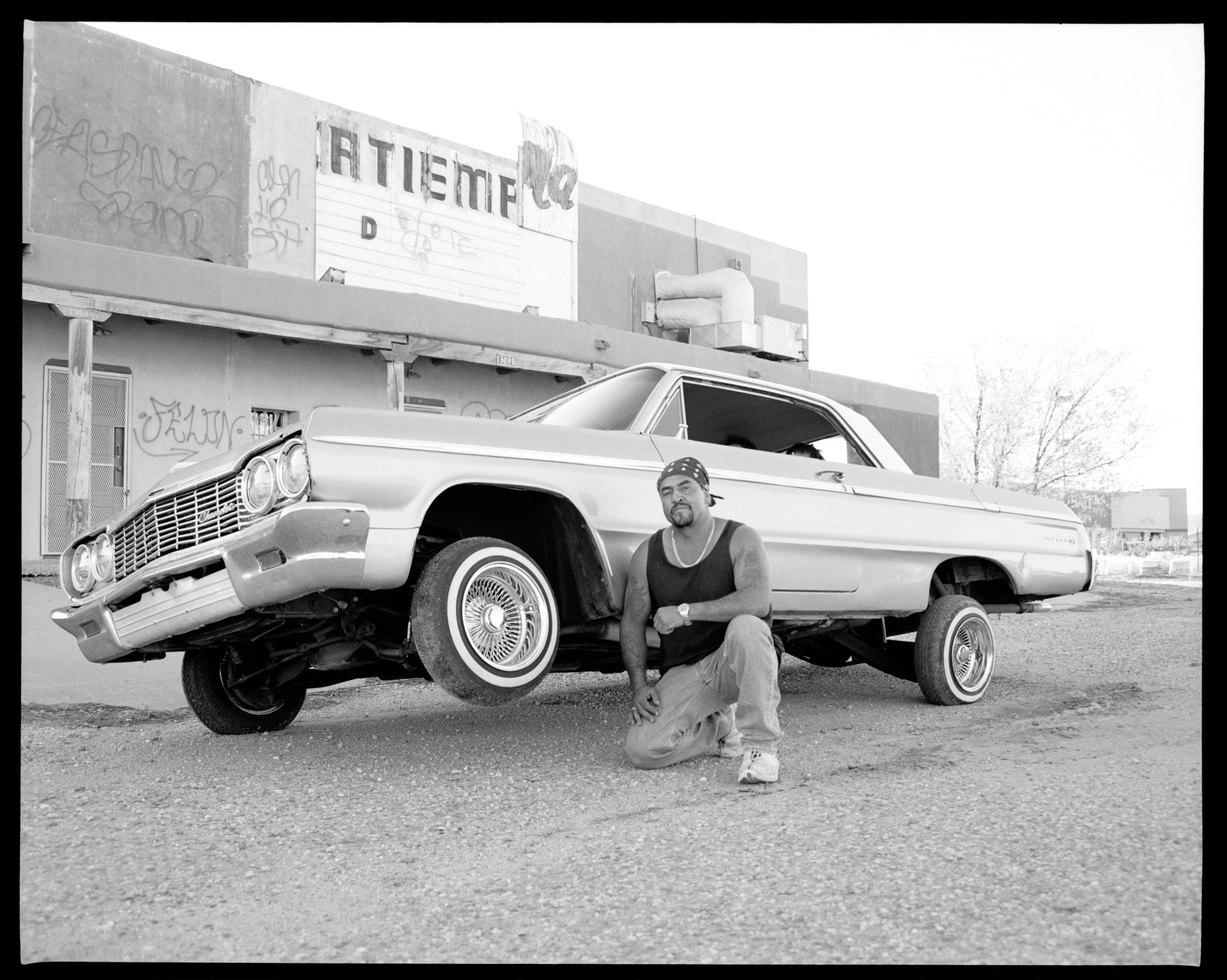

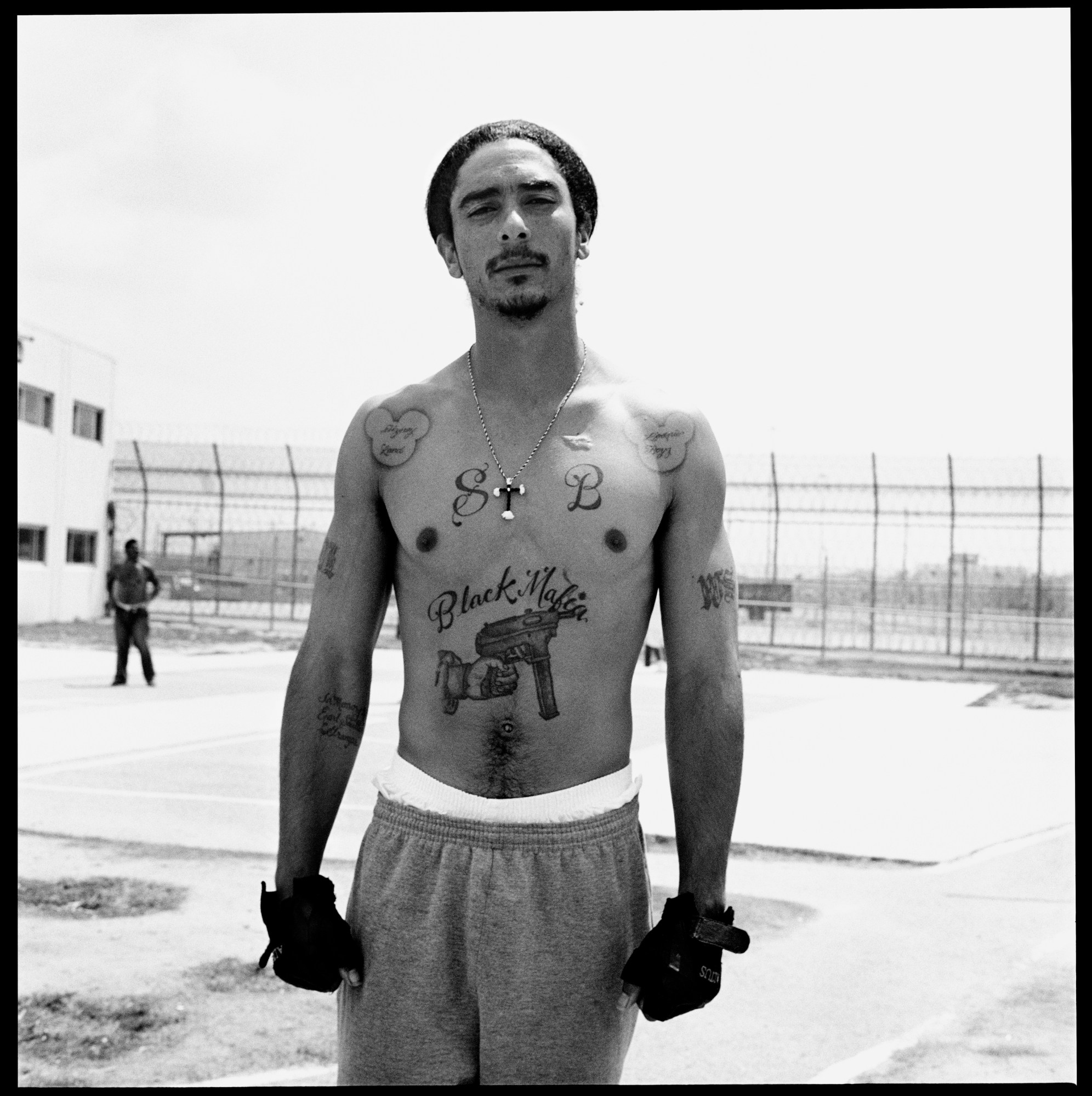

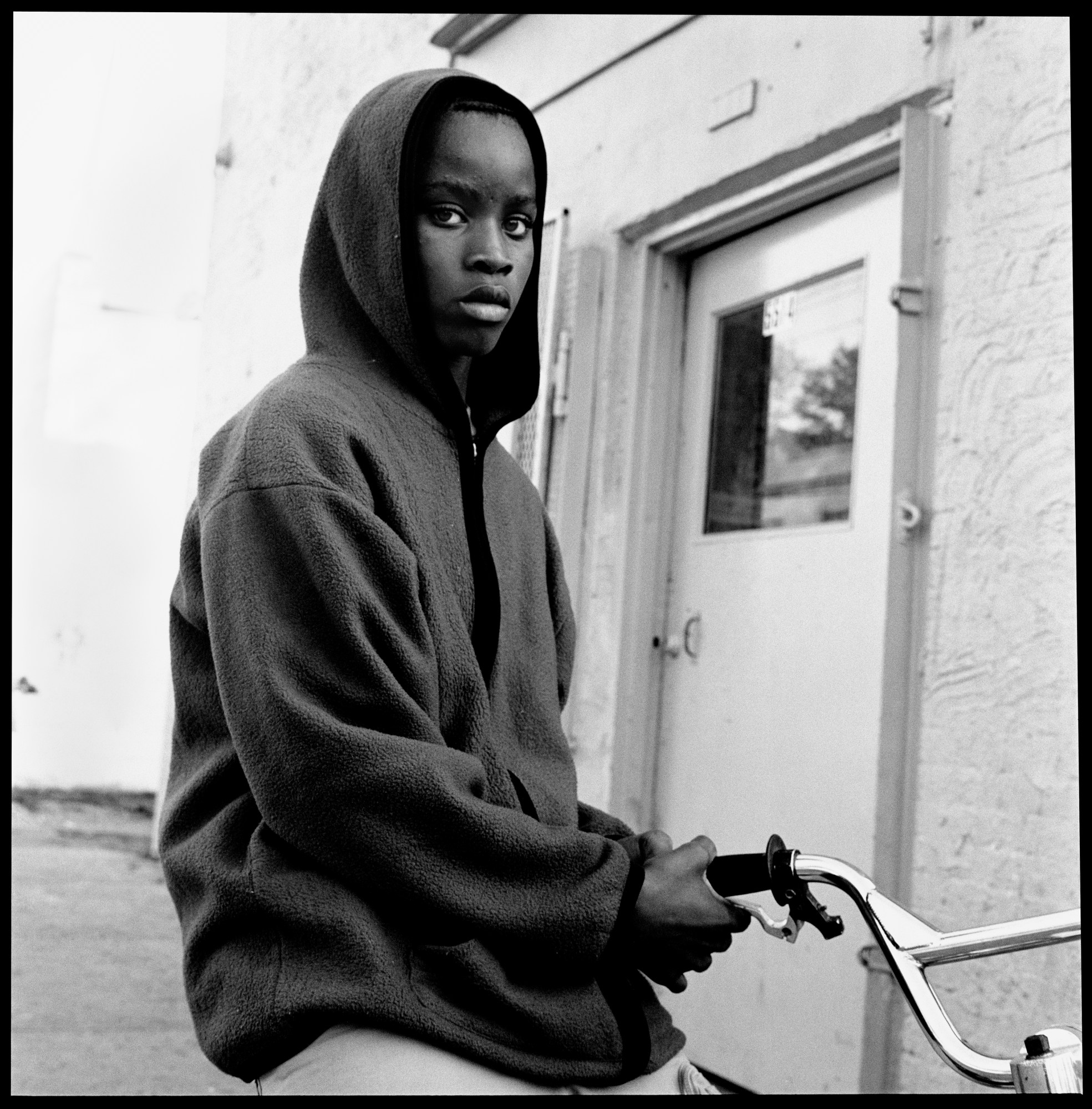

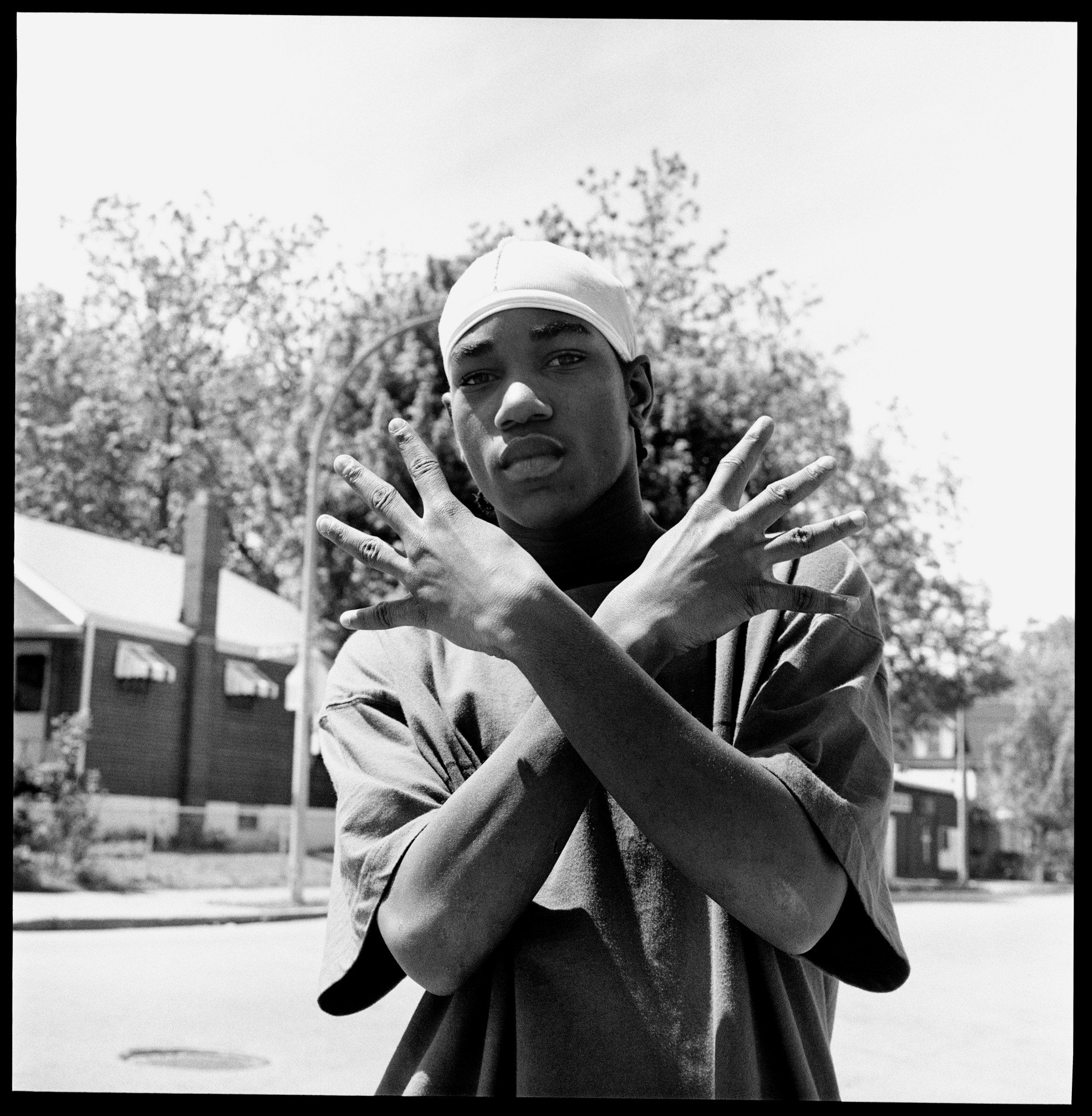

Outside of Life: Lowriders, Coolers, Bikers & Bloods is a photo book by Hunter Barnes that was initially self-published in 2003. It spotlights fringe American communities and spans regional motorcycle clubs, car clubs, gangs in St. Louis, and California State inmates. Barnes united these disparate groups at the turn of the 21st century as a set of compelling subjects. Now, nearly 15 years later, the black and white photos will be shown in an exhibition at David Hill Gallery in London through December 20.

For Barnes, the subjects of the series were magnetic because of their remoteness from the American mainstream and making these images required a great deal of trust. “Outside of Life” was shot on film, both because he describes himself as “old-school” and because analogue fits nicely with his slow-cook approach. His series was shot before the arrival of Instagram, but his body of work as a whole seems to refute the digital age and its impulsive values. As a result, his patience delivers a potent form of testimony.

The American photographer’s projects since 2003 have varied—years spent with the Nez Perce tribe, months with a serpent-handling congregation in the Appalachian Mountains, a dicey mission amongst the Tamil people in Sri Lanka—but are underpinned by a desire to explore communal identity. Barnes discussed his fidelity to analogue photography, his experiences, and why showing up to introduce yourself—in person—inevitably gets you in the door.

How did these four series from “Outside of Life” come together?

It was a year on the road; I was in my early/mid 20s. I went pretty hard, fast… at that time, I barely had money to process the film—I don’t even know how I pulled the project off! I slept in cars, or people let me stay in their places. I didn’t even have contact sheets made back then—I still don’t, for some of the work. I started shooting photographs of friends of mine who were bikers. That same year, I ended up out in the desert because I’d heard about the low riders out there—Española in Chimayó, New Mexico is a low-riding capital. I went on this trip and was blown away. I thought those two would fit. And then somehow, naturally, I was introduced to a guy who was in the Bloods… and I shot in California State prison because some people from the Bloods landed there. I ended up getting access to the yard.

When you say you had a natural introduction to the Bloods… what do you mean?

A friend of mine was taking photos for different hip hop record covers; he knew some of those guys. I told him about this book I was doing. He said, ‘You’re going to have to come to the neighborhood and introduce yourself.’

What happens after that introduction? Your series are usually immersive and happen over several years… Do you do research, or is it intuitive? What is that negotiation between feeling part of a community versus maintaining enough distance to document it?

It’s a responsibility to understand who the subject is and, at the same time, that they understand what you are doing. If you want to portray somebody in the right way that’s honest, you need to know who they are and where they’re from. But they have to trust you—they wouldn’t let you do what I do if they don’t trust you—for them to be comfortable and take me to the right place. It is a long process.

When I first started, I would take a box of prints so I could show ‘em what I was doing. That way they can see the work. I’ll ask them when’s a good time to be there—once everybody’s agreed to it—to come back in town and actually plan it out. As far as researching ahead of time, I don’t do a ton of it. Back then, I didn’t do any at all. In 2003, you weren’t really on the internet. It was people I met and gut feeling. Still to this day: a little bit of research is good, just as far as navigating around a little, but you don’t really want too much if you wanna get the real thing—people will show you what that is. It’s almost going in with a preconceived notion if you’ve done too much research. I feel like once you make friends, you’re down with everybody, and they have an understanding, they’ll open up that side of their life that you’re supposed to be exposed to. I like meeting people that way. I’m old-school in a lot of things. I show up on time. I still stop at gas stations and ask for directions when I’m on the road. Developing relationships takes time, and the process does too because everything I shoot is on film. There’s something about it: there’s a spirit and soul to it. The projects, I would say, from start to finish, are usually about two years.

How did you decide to become a photographer? Who influenced your eye or aesthetic?

A cousin of mine was a photographer and exposed me to a camera. The original influence was 60s-70s psychedelic artists, like Rick Griffin. They were doing everything that they wanted, putting out there what they were really seeing and feeling. When I went to school, I trained in photochemistry. I didn’t go to art school; what I was learning was very technical. I moved to New York after and became a photo assistant. I worked for some cool people in a commercial industry, and I wasn’t feeling that that was what I wanted to do. I met a girl, and fell in love with her, and went out to very small town where she was from. Those were some of the first art patrons of mine. They gave me places to live, cabins out in the mountains, with barns that I could print in. I had whole buildings for my art. I did my first book when I was 22; it was called Redneck Roundup. It was all these old-timer ranchers and hillbillies. It hit me that these people weren’t going to be around much longer—the kids who were going to inherit the ranches had zero desire to become farmers. I saw them fading out, and asked if anyone had ever documented their lives. No one had—so I moved out there to do that project. That’s how it started.

Do you feel your ability to infiltrate different communities has changed over time—especially since the way people consider photography as a medium has changed?

People always say I infiltrate these places… I’ve never looked at it like that. I’ve introduced myself, and they’ve invited me into their home. It’s an extension of being invited into somebody’s life and into their world. I’m always grateful for that. I just got off the road for a project I’m not telling people about yet, but I was nervous because didn’t know anyone in the community. It’s really a sensitive place; people really had to trust me to do this. I came with my books and introduced myself in person—I initially emailed someone, and that didn’t fly. So the approach hasn’t changed. And people are intrigued that it’s all being shot on film. A couple people were like: ‘When can I see the pictures?’ And I was like ‘Well… I shot 60-something rolls; it’s got to be processed.’ And I need to not look at it for a month or so, because otherwise you get emotionally attached to certain images. Also, because people have cell phones now, I was worried they’d just be looking on their phones, but they didn’t. I kept my own phone away the whole time.

You’re described as a documentary photographer—would you qualify this as different than a portraitist? Given that you build and cultivate these relationships, it seems less neutral than documentary.

I have a degree and know about photography, but I’d never heard the words ‘documentary photographer’ until someone said: ‘You’re a documentary photographer.’ Shit, I guess I am! Alright! It was something that just kind of happened. I guess it doesn’t really matter, but you’re right—I do take portraits of people primarily. There are very few photographs that don’t have somebody in them. And I’ve always wanted the subject to feel right about it. You can spend a month with somebody, and then all of a sudden, one day it’s the time to do it. You end up taking a few frames, less than a roll of film… You can feel, mutually, that you got what you were supposed to. The way somebody feels about the image is very, very important to me—I would never want to be the type of person taking a photo of a picture of somebody when they don’t know what my intentions are and what I’m doing.