This story originally appeared in i-D’s 40th Anniversary Issue, no. 361, Winter 2020. Order your copy here.

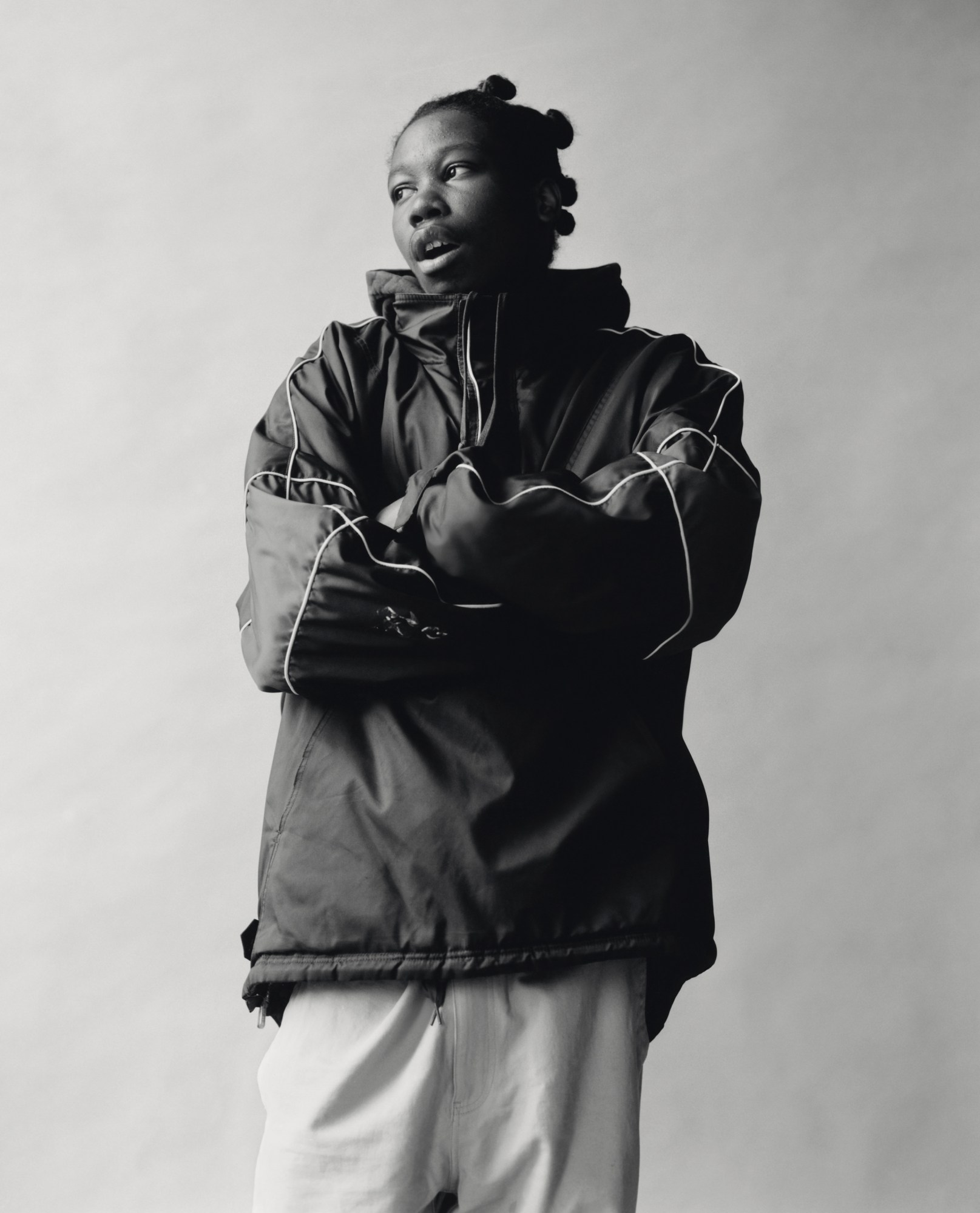

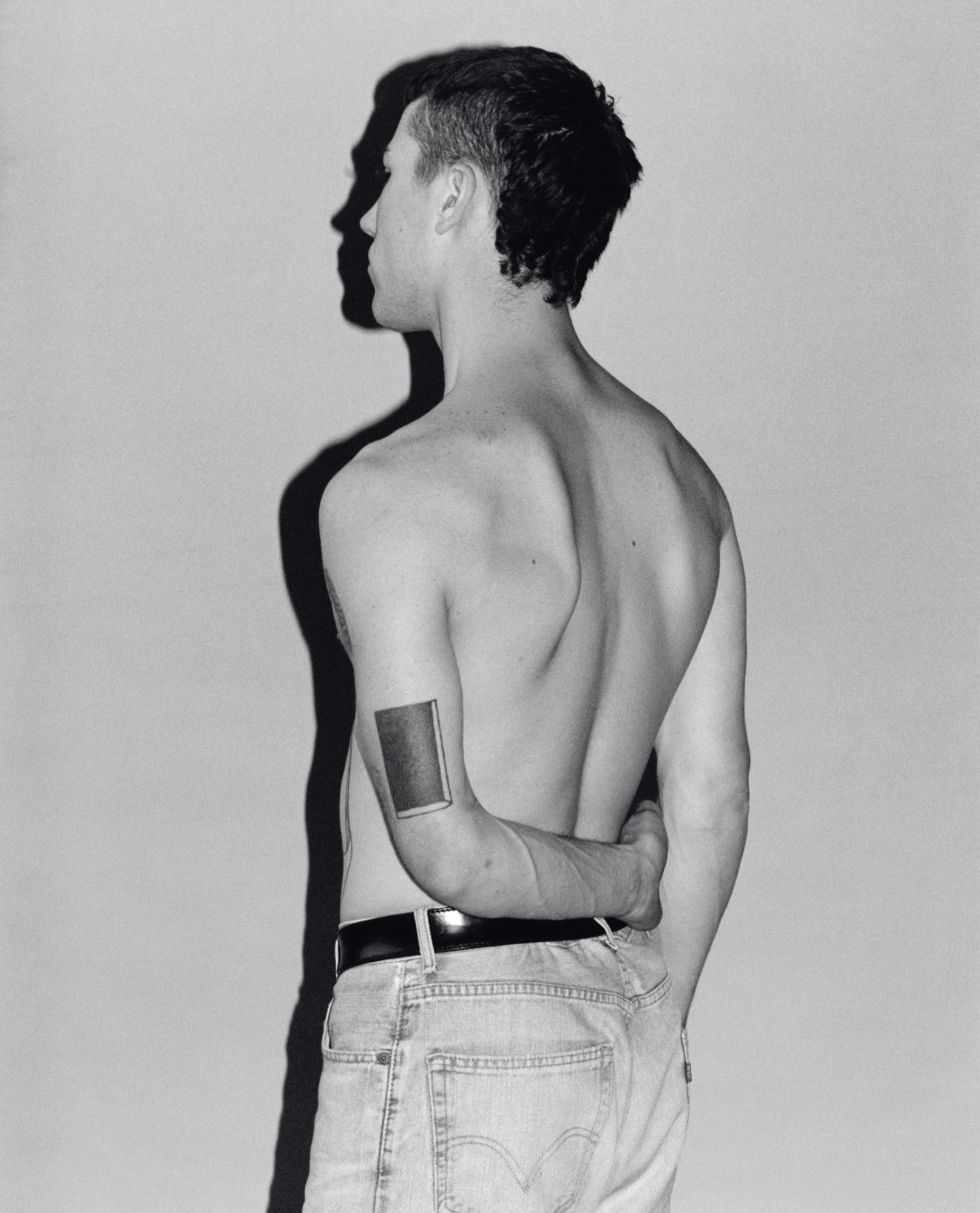

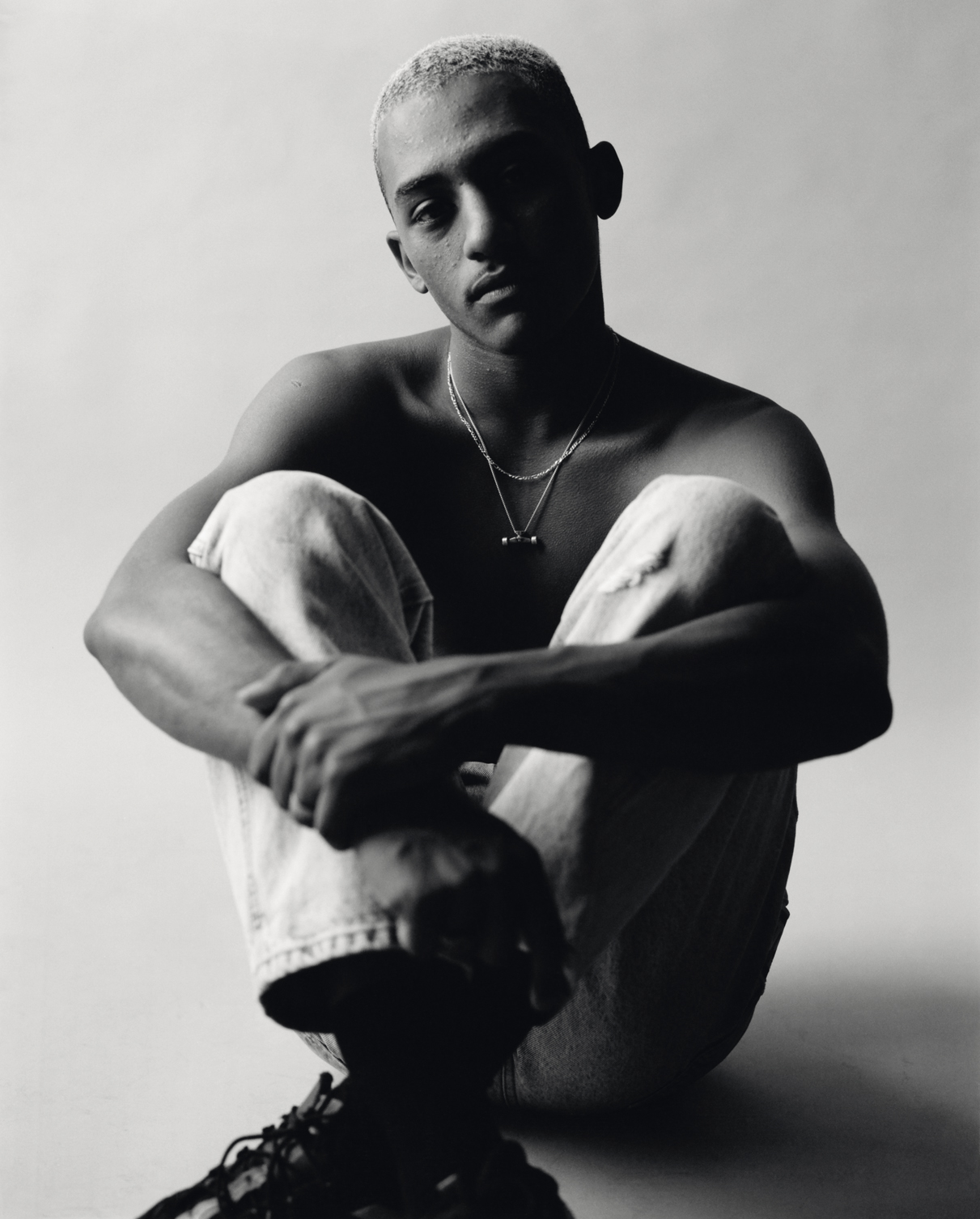

The collection of portraits on these pages spans the last five years of the work of Lola Paprocka and Pani Paul, who are from Poland and Australia respectively but are based and working in London. And it is here, they’ve set up a photographic practice that documents the innocence and experiences of youth in the city. This body of work focuses on their studio portraiture, rather than projects they’ve undertaken across the world, in their countries of birth and further afield .

There’s something pure about a portrait, shot in a studio and captured on film, a continuum that stretches back to the beginning of photography. These images capture the raw and unrefined truth, the sitter and what they’re wearing and how they hold and present themselves to the world. It’s photography as the uneasy balance between performance and reality, how we dress and how our attitude mediates between how we see ourselves and how the world sees us, the roll of a trouser or the cut of a hoodie or the logo on a T-shirt that stands in for who we are. These photos are so interesting and exciting because they present that dichotomy so simply and with such forceful poetry.

Below, read Lola & Pani in conversation with i-D’s Editor-in Chief and Creative Director Alastair McKimm. You can buy their book here.

I was first drawn to how in-depth the project is, this idea of finding characters and documenting them in an intimate way. Can you tell me a little bit about your casting process?

Pani: After I made the Mile End book about the local skatepark in 2015, which Lola curated and published, we began working together as a duo. One of our first projects was to invite some of the people from that book into the studio and photograph them again. It sort of just snowballed from there.

Street casting has become part of the language of fashion photography and a lot of interesting kids are represented by model agencies, but what happens in this book feels so different from that because of the connection you have, there’s a sense of community that comes across.

Lola: The aim was always to represent that feeling of community, but there’s a strong feeling of sentimentality in this work for us also. It reminds me of myself at that age.

“This project, for us, feels like it might not have that immediate impact, but in a way it’s kind of a ‘historical document’, a book of portraits of people that existed at a certain time.”

There’s definitely something special about that time in our lives, it’s that mix of independence and naivety that’s just beautiful, you start discovering yourself but don’t have the responsibility of adulthood. I grew up in Northern Ireland but I was very much inspired by American street culture and I love the mix that globalisation brings. People taking different bits from everywhere and putting them together in a new way and that’s why it keeps evolving.

Lola: Growing up in Poland in the late 90s if you saw someone in a Wu-Tang T-shirt you knew it’s because they were into them. The way that subcultures have been adopted by mainstream fashion means today’s youth really need to work hard to find something in order to stand out.

Pani: The people we photographed are the kind of personalities that are more interested in a DIY approach to style. A lot of them make their own clothes or have their own label and that’s something we can relate to, things like that help us make a personal connection.

Have you noticed a lot of changes in the skate scene since you published Mile End?

Pani: While this work isn’t about skateboarding per se, it does have ties to that community. Probably the main difference is how many girls are involved now. When I was growing up there were not many girls skating at all. Now, it’s huge and the younger guys are really supportive. The Mile End book was only five years ago and there weren’t really any girls skating there then, whereas now they’re taking over, which is awesome. It’s a very transitional time period now, it’s becoming more inclusive and you can see that in the cast of characters. But again, it’s not about skateboarding, but it’s a good representation of change among people.

Something else that I wanted to talk about was the role of shooting on film and not digital, obviously you thought that was important to the project?

Lola: Aesthetically we knew it was going to be nicer on film, the process is so much slower so it creates a much more personal dynamic between you and the subject. They don’t get to immediately see themselves on the camera and they begin to relax a bit more.

Pani: With having cameras on our phones, people have become so used to performing for pictures. But I think the more old-fashioned set-up you get with film, with the big camera on the tripod, sort of snaps them out of that. Most people come into the studio and the first thing they say is ‘what should I do?’ or ‘how should I stand?’. Lola: We tell them to do the same thing they would if they were waiting at a bus stop, just be yourself within the space.

When I first started we were only shooting film and it was a crazily expensive process. Then digital came in and really took over and from what I remember, after only one or two seasons or maybe just over a year, we weren’t shooting film at all.

Lola: We’re not against digital, this project was film-friendly and it brought what we needed. But with others, like ones with a lot of motion or spontaneous movements, we’ll work on digital. Why would you want to complicate things with a massive camera and run after someone when you can do it so much better with digital?

I think that’s totally the right approach. There’s no sense in doing something for the sake of it. It’s more about using the tools that work for that moment whether it’s digital, Polaroid, large format or iPhone. I love this idea of the role traditional portraiture plays in the digital world. You kind of already spoke about it a minute ago, this idea of how subjects perform differently in front of different formats.

Lola: When we were taking these photographs, we were trying to see them as something that we’ll still get excited about in 20 years’ time. It’s interesting trying to find these little things that are so commonplace that we might not appreciate them now, but in 15 or 20 years will define a moment. It’s the same as when we look at images now from the 90s or early 00s and everyone had a Nokia or they had this pair of trainers or whatever. When it was happening it wasn’t spectacular or interesting at all, it’s only with time that it becomes this way.

For our generation, looking back on images from the 90s gives me so much comfort because it makes you feel like you weren’t alone in the process of life. I guess today what’s going on with Brexit, climate change, the Black Lives Matter movement and the COVID-19 pandemic, it feels like such a hugely monumental moment in time.

Pani: This project, for us, feels like it might not have that immediate impact, but in a way it’s kind of a ‘historical document’, a book of portraits of people that existed at a certain time. Our hope is that this generation will be able to revisit this project with the same sense of nostalgia we do with images from the 90s.

Lola: People who are participating in this book understand the importance of what is happening right now and that can only give us hope, right?

That’s a beautiful place to end, there’s hope in the new generation.

Credits

Photography Lola and Pani