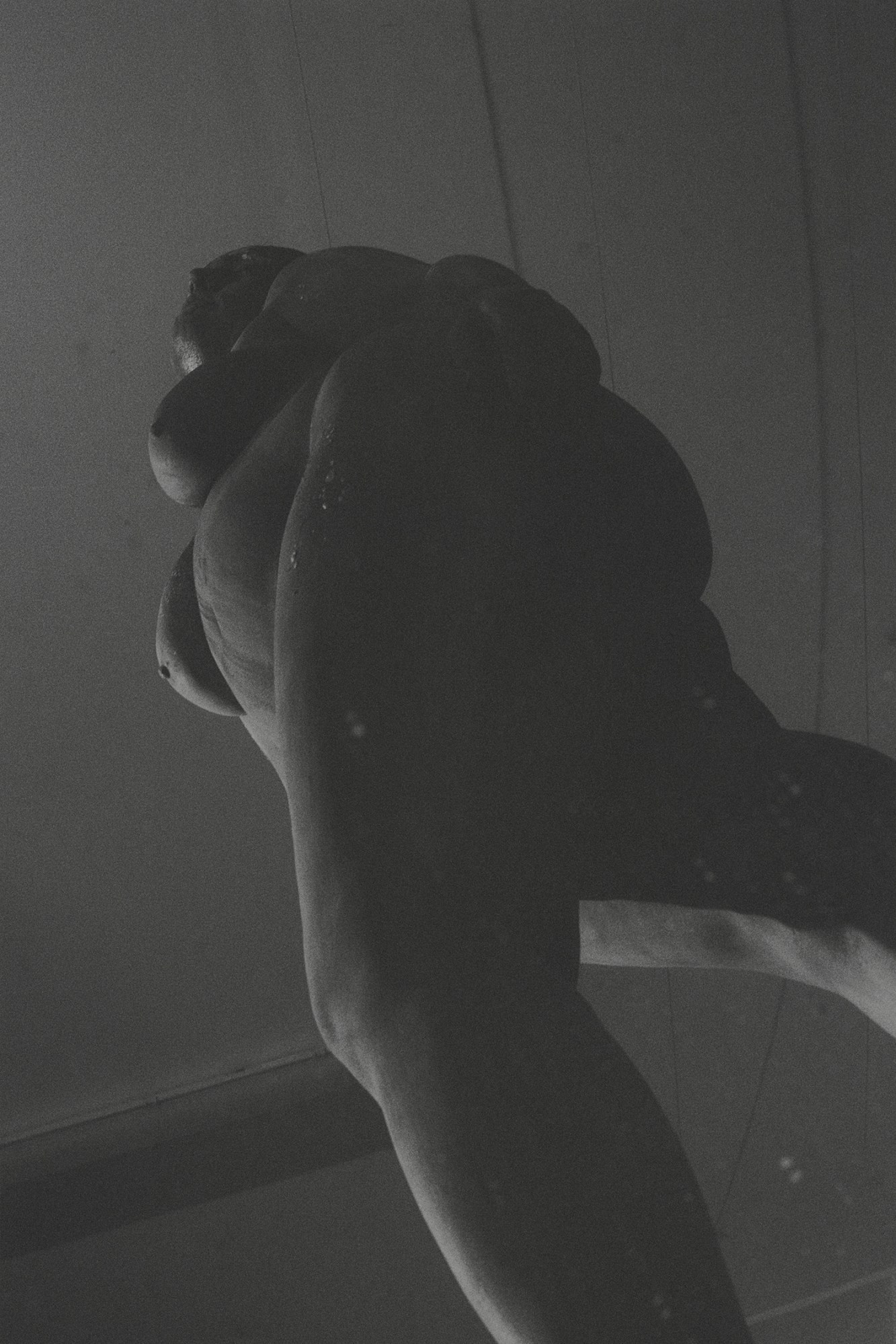

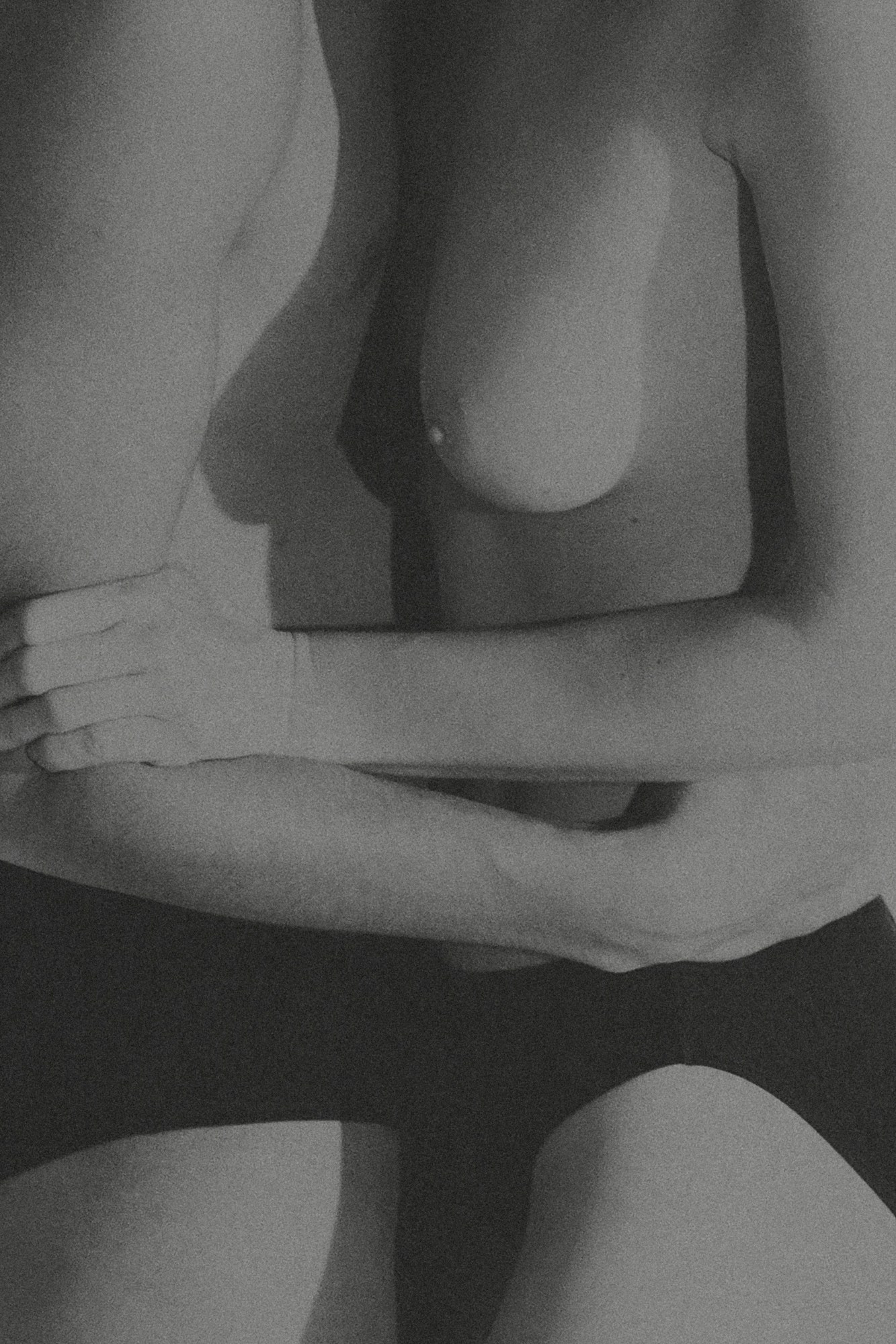

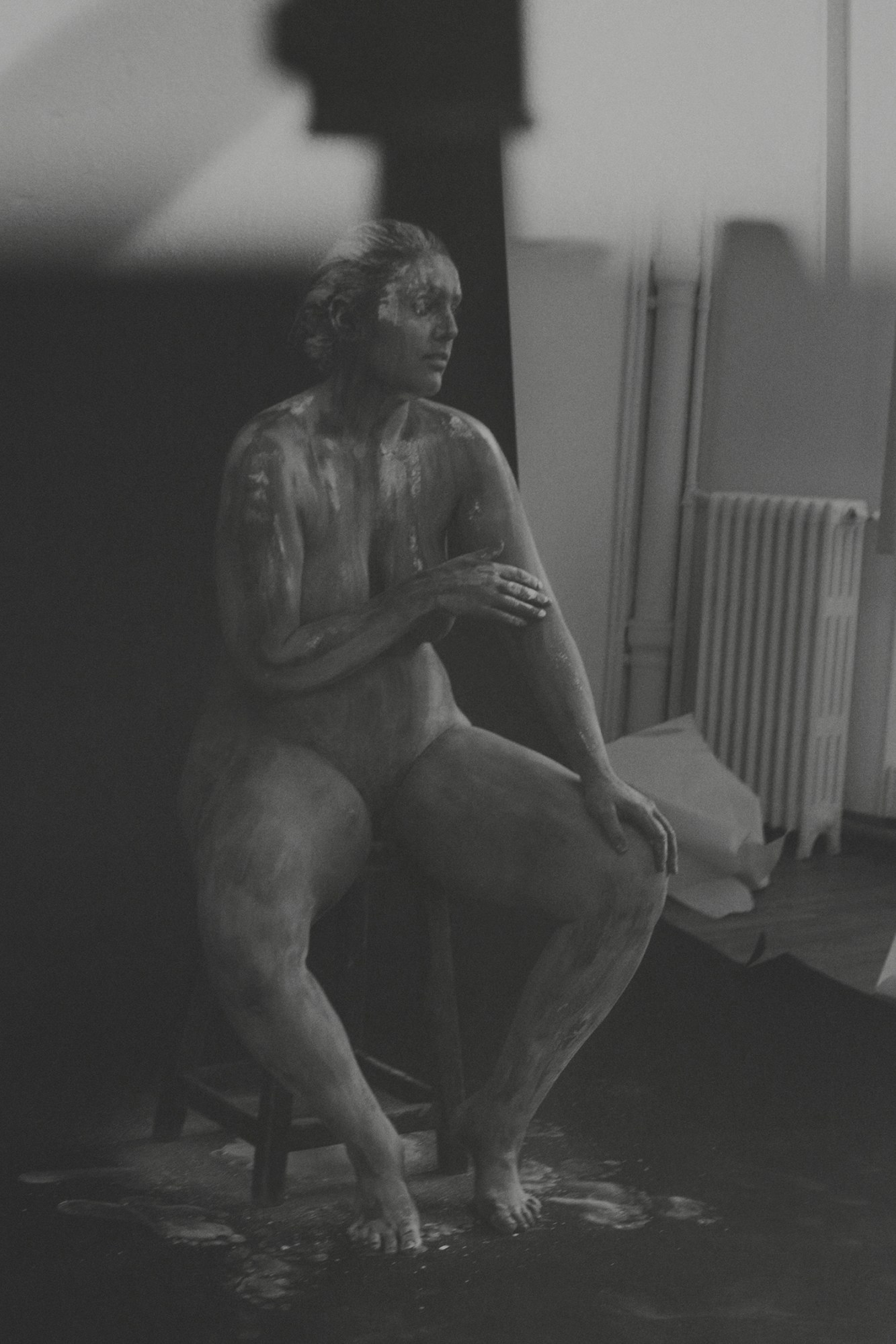

Pascale Arnaud, one of the young photography finalists of the 2018 edition of the annual Hyères Festival International de Mode, de Photographie et d’Accessoires de mode in the south of France, was selected to showcase her black-and-white series Emerging Adulthood. The Paris-based photographer focused on depicting that limbo chapter between the caprice of adolescence and the looming responsibilities thereafter, using — appropriately enough — a gray scale of tones and textures to highlight the sense of ambivalence and uncertainty. Printed on specialized gray paper from Japan, the aesthetic has a fine grain and a sense of effervescence in the accentuated particles. Arnaud’s subjects, who are also her friends and artists or photographers themselves, are offered up as silhouettes abstracted into sculpture with body paint and mirrors.

Arnaud, who graduated from prestigious Parisian art school École de l’image des Gobelins, currently assists fashion photographer Paolo Roversi. She discussed being influenced by a young generation of photographers, her curiosity about gender fluidity, and asking her subjects to scream.

How did this series come about?

I do some fashion photography with models, but it was important to me to photograph people who are close to me. With a personal project, it’s easier to communicate emotion through people you know. The series is about exploring identity, figuring out relationships, nostalgia but also fear of the future. It’s also about the vision you have of your own body and body dysmorphia—when you exaggerate a body complex.

What age spectrum did you qualify as “Emerging Adulthood”?

I didn’t have anything exact in mind, because it’s really according to how people feel. There are thirty-year-olds who don’t feel like adults. You could do a median — ages 18-25 — but I think that that phase before adulthood is very personal and individual.

What’s the vibe you try to create on a shoot?

The series was photographed in four shoots over two months. There is always music playing. What I do is make my subjects talk — I do this for fashion shoots, for any photos I do. It’s a way to transcribe interesting expressions. I ask questions and when I get answers, I then tell the subject to freeze when I seize on something I like. In the photo where my friend’s mouth is open, it’s halfway between a yawn and a scream. I said: pretend to scream — or actually scream.

I like strange poses — I try to avoid expected poses, and classical fashion photography like [puts her hands on her waist]. I really want to steer clear of that; I want other things to come to the surface.

With models I don’t know, I ask questions in order to get to know them better. Or I put the music on really loud and tell them to sing along. It’s a way to make things come out without having to get too psychological.

Were there any referential photographers you had in mind when you created this series?

There’s no one name. I’m assisting Paolo Roversi at the moment, and he has an impact. I like young photographers — Marton Perlaki, and Nhu Xuan Hua. There’s a whole generation of photographers in their 30s that influence me a lot… Their aesthetic looks nothing like mine, but their photography is zany, with bizarre poses. I like unconventional portraits.

How do you approach nudity? What did you hope to showcase about the female body through the series, or question about perceptions of it?

In a nutshell, my approach to photographing women nude is about everything except sexualizing the body. Really. I did this series of nudes with six, seven friends of mine, and I wasn’t looking at them as “women”; I was looking at them as “bodies.” I try to make them beautiful, or at least interesting, and to find interesting angles, without retouching. Everything we see as some kind of “complex” can be beautiful, can be aesthetically pleasing. It’s part of the current of conversation right now, and I want to participate, in my own small-scale way, to make people—women in particular—feel less inhibited by body image.

Bettina Rheims was at the head of the photography jury for this edition of Hyères, and has portrayed women very differently, with a much more overt focus on sexuality.

Her photographs are from another era. At the same time, it’s a feminist debate, and it can go in all kinds of directions. I haven’t resolved the question for myself—I’m still exploring what I think. I don’t think it’s bad, it’s just not my way of doing things, and it’s not how I myself want to show the women I photograph. I myself have a certain reserve or reticence about putting models in hyper-sexy miniskirts. That’s not me; I wouldn’t do that. I want to show the body the way it is, especially without Photoshop.

You’ve done a series in China, called Xiatong —did photographing in a different cultural context reframe your notion of femininity or emerging adulthood in any way?

I took these photos in the city of Hangzhou. I met this arts student. She barely spoke French, and I don’t speak any Chinese. On top of that, she was very shy and reserved… She was quite serious and didn’t smile much, but I hoped to be able to reach something in her. Through the portraits I took of her, I could feel so strongly that she was in that emerging adulthood phase. I did this series right after “Emerging Adulthood,” and it feels linked, even if it’s aesthetically different. I tried to highlight the commonality of that phase because, even on the other end of the world, everyone goes through it.

What else is next for you?

I want to address the question of gender, because it’s part of emerging adulthood. There is so much to question. I want to photograph faces that are interesting—transgender, gender-free. The image I showed for the American Vintage Photography award at Hyères was a photograph of a boy, who dresses like a girl every few days. Sometimes he looks like a boy, sometimes a girl… I’m interested in that mix.