“I would like to begin our conversation by stating one important point,” photographer Seiichi Furuya tells me from his home in Graz, Austria. “I may mention details of events, dates and chronologies, but my recollections would not have been possible without the photographs and diaries that belonged to Christine and I. In other words, these past scenes have not been reached by digging up memories in my mind, but recreated in the present with the help of two mediums of expression: photography and language.”

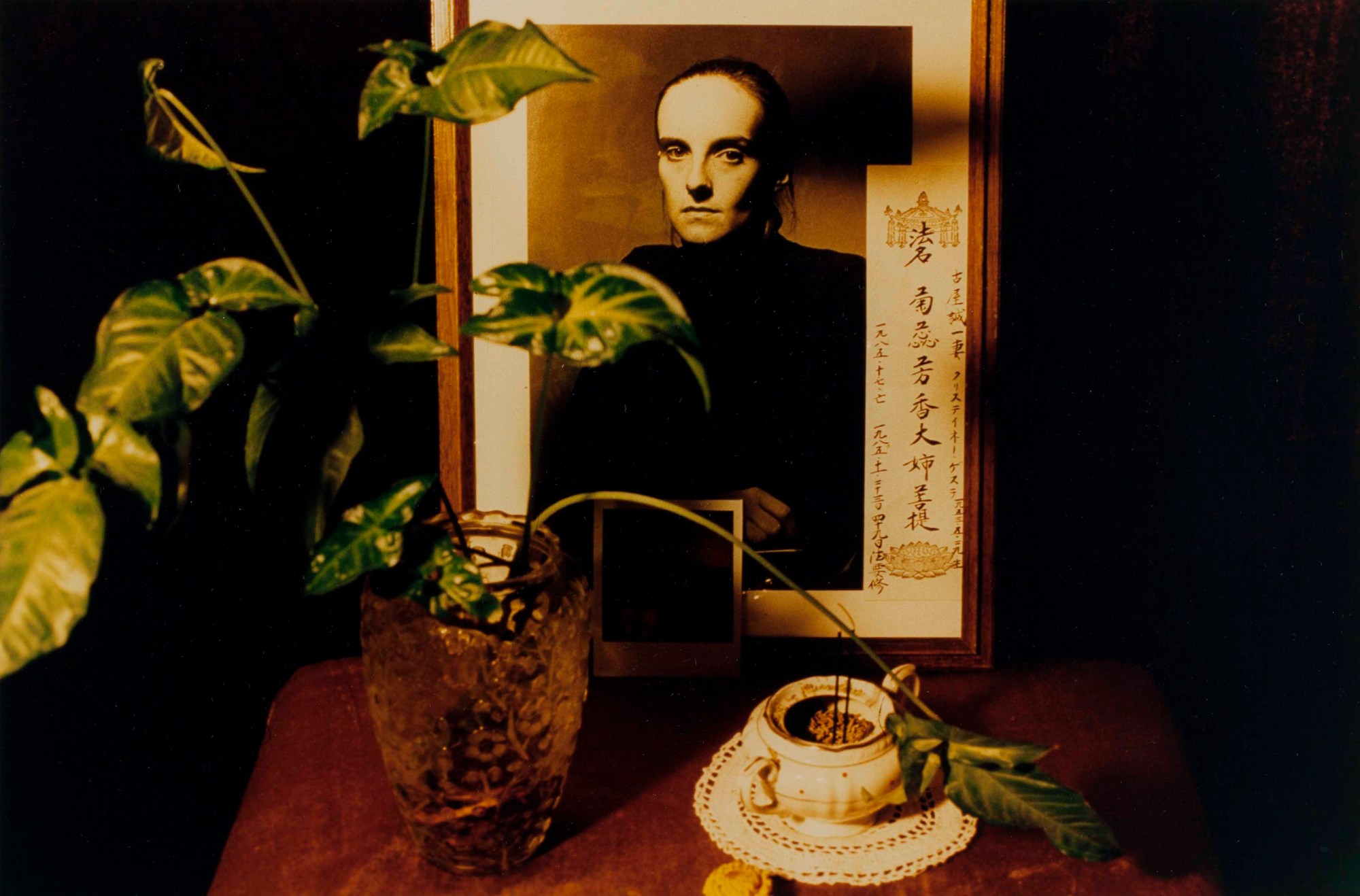

The “recreations” Seiichi mentions refer to an ongoing series of exhibitions and books, collectively entitled Mémoires. It’s a work of heartbreaking simplicity, dealing with the life and death of his late wife, Christine Gössler, who he married, had a son with and photographed dutifully until one tragic day in 1985, when she jumped from the window of their Berlin apartment. “I think it was in 1996 that I began, in earnest, to sequence the photographs I made of Christine,” Seiichi says. “That was around 10 years after her death. After the first Mémoires exhibition in 1989, new questions began to haunt me… When and how did Christine’s circumstances change? What was my involvement with her tragic end?” The questions of “when, where, what, with whom and why?” only intensified as Seiichi began trying to make sense of what he calls the “swirling maelstrom of memories” through his increasingly complex photobooks. But these questions are the driving force behind Seiichi’s life’s work, and he makes no apologies for their falling into empty, silent air.

Seiichi’s newest exhibition, staged at Tokyo’s historic Shadai Gallery, is structured in two parts: Wife (1978–1981) and Mother (1982–1985). The presentation derives from the 364 photographs — the bulk of which were printed on pebble-textured charcoal paper in 1997 — which the gallery acquired earlier this year. Here, the enigmatic photographer opens up about his life with Christine, her actress ambitions and the wonders and horrors of photography.

You once told me that your relationship with Christine “began and ended with suicide”.

Yes, I remember. I met Christine on 17 February 1978. She showed up with a friend at the opening of a photography exhibition in Graz. Afterwards, there was a party at a restaurant, and “apparently” she was there. I say “apparently” because I have no recollection of the event myself, but Christine’s diary reveals this fact.

Ten days later, I rang her up at work (she was studying art history at university and working part-time at a museum). I asked her if she would go on a date with me to see the Japanese samurai movie Harakiri (1962). That night’s diary entry contains the following record: “I invited her to a movie, but I was a little late. Christine seems a little angry. I am concerned about the scars on her neck and wrist.”

When I told you our relationship “began and ended with suicide”, it was because the scene of Christine’s suicide overlapped in my mind for a moment with the scene of the movie we saw on our first date, in which a man commits harakiri (ritual suicide by cutting his stomach open).

Can you remember the first time you photographed Christine?

Again and again, I fail to remember many specific details about our relationship. I cannot decide whether this phenomenon of not remembering is unique to me or a characteristic of human beings themselves. Occasionally, I learn certain facts with the help of photographs and diaries. But just because I know the facts, I do not necessarily recall what happened.

I learned from Christine’s diary that she was photographed at 6:15 pm on 28 March, the day after our first date. I checked the negative film, and I found the first photograph I ever took of Christine. After I took several consecutive shots of her, she took several of me. All the shots I took of her were underdeveloped and almost impossible to print, while the shots she took of me were all properly exposed. I was very surprised to discover that we had been photographing each other from the beginning. This “first photograph” graces the first page of my book Face to Face (2020).

You married pretty quickly, right?

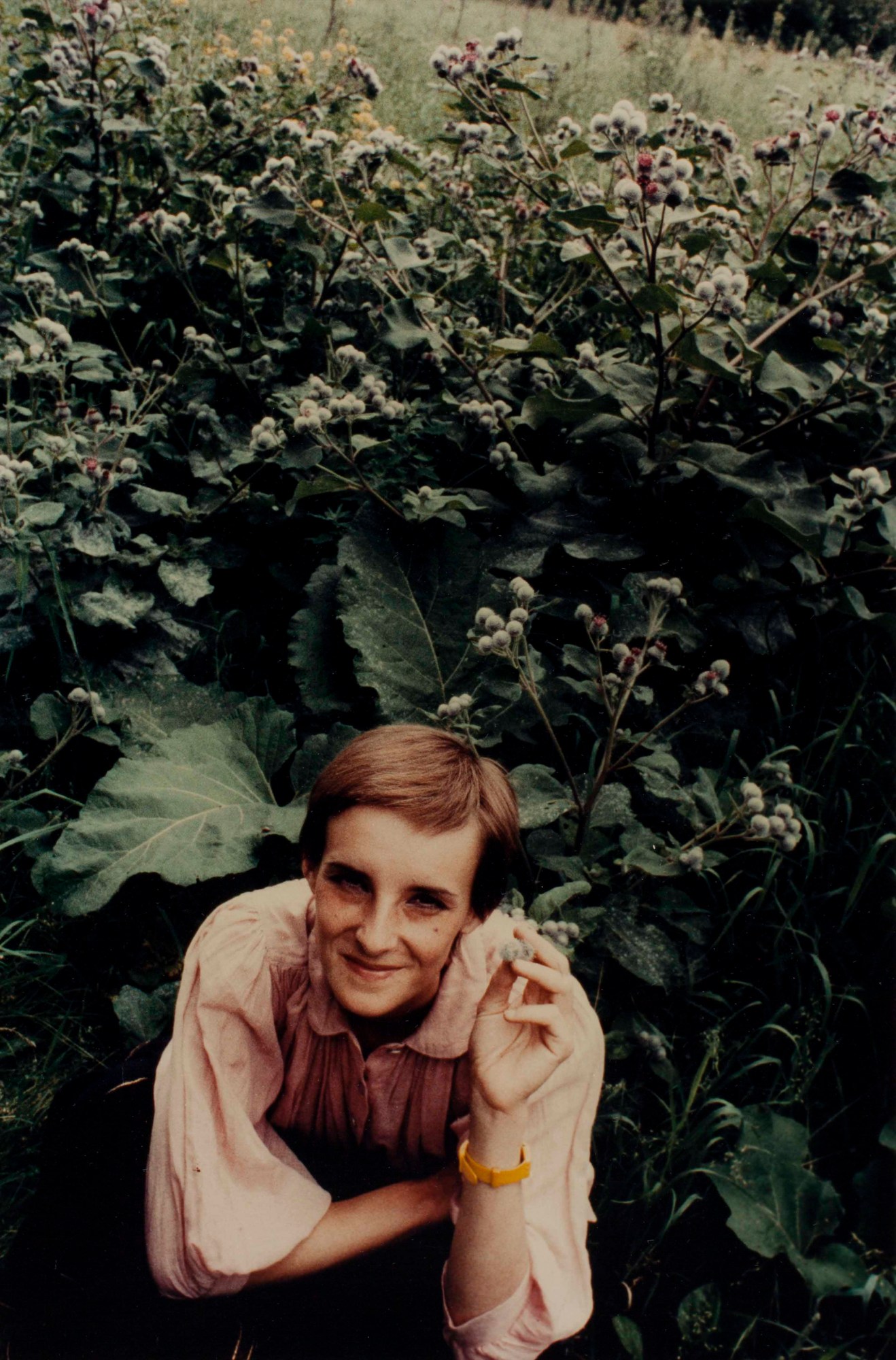

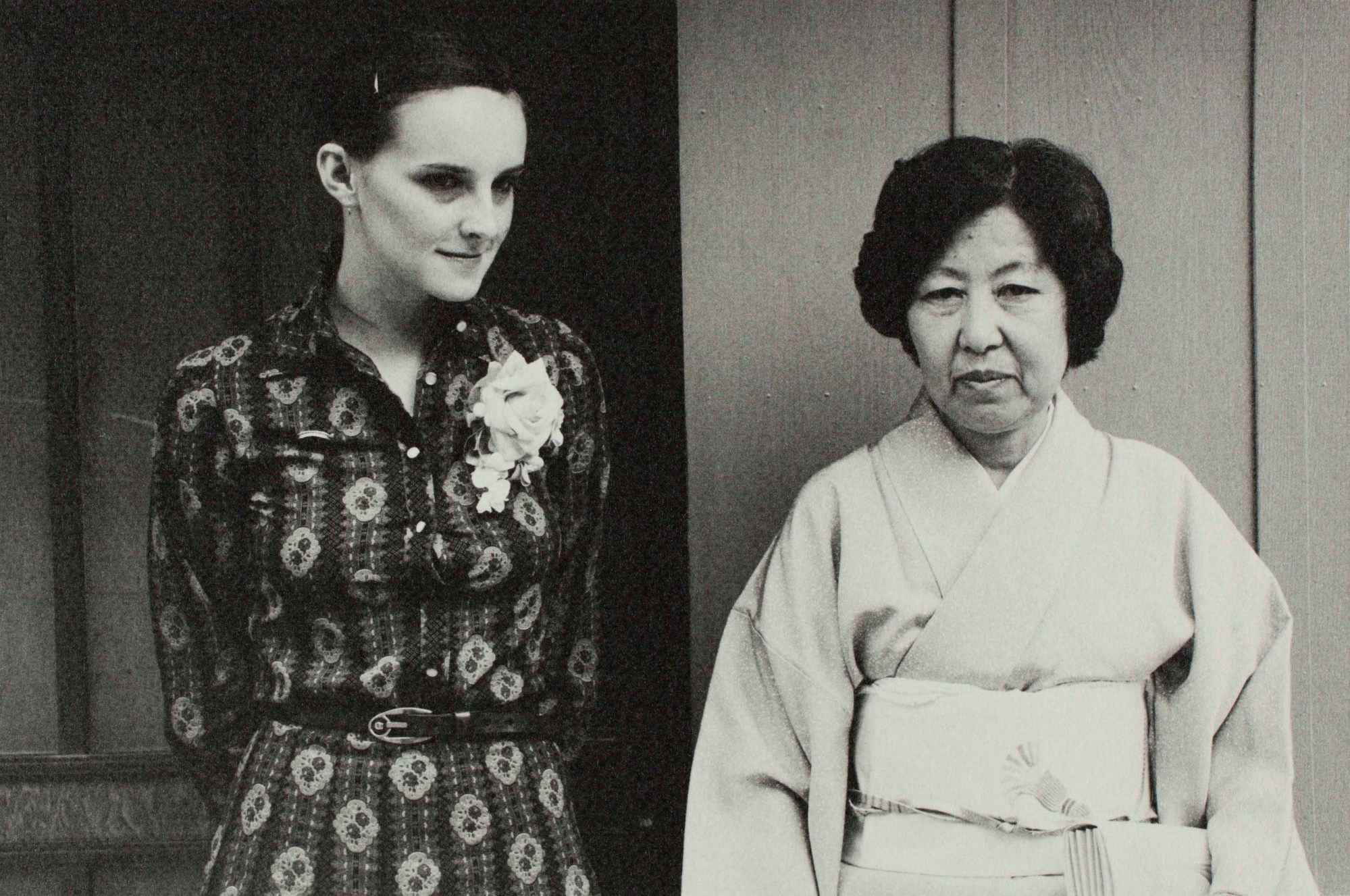

Four and a half months after we met, we were married at a small Shinto ceremony in my hometown, Izu. The photographs taken by a friend of mine show Christine’s confusion in a smiling and almost innocent way. In retrospect, I am sure that, for Christine, the trip to Japan was an “otherworldly” event, where everything was sudden, new, strange and passed by in the blink of an eye.

What was Christine up to in those early days?

When we first met, Christine was studying art history. However, in the summer of 1979, she gave up on her thesis and found a job as a secretary at an Austrian broadcasting station. Although she started in the radio department, she began creating and airing her own monthly documentaries titled Woman and the Working World.

During a clean-up of my attic in 2018, I found about 20 cassette tapes that Christine made during this time. I half-heartedly put them into my dusty cassette deck and pressed the play button. Suddenly, I heard her familiar, never-to-be-forgotten, lively voice. I was so stunned that I thought my heart was going to destroy itself.

Can you tell me about the origins of Christine’s actress ambitions?

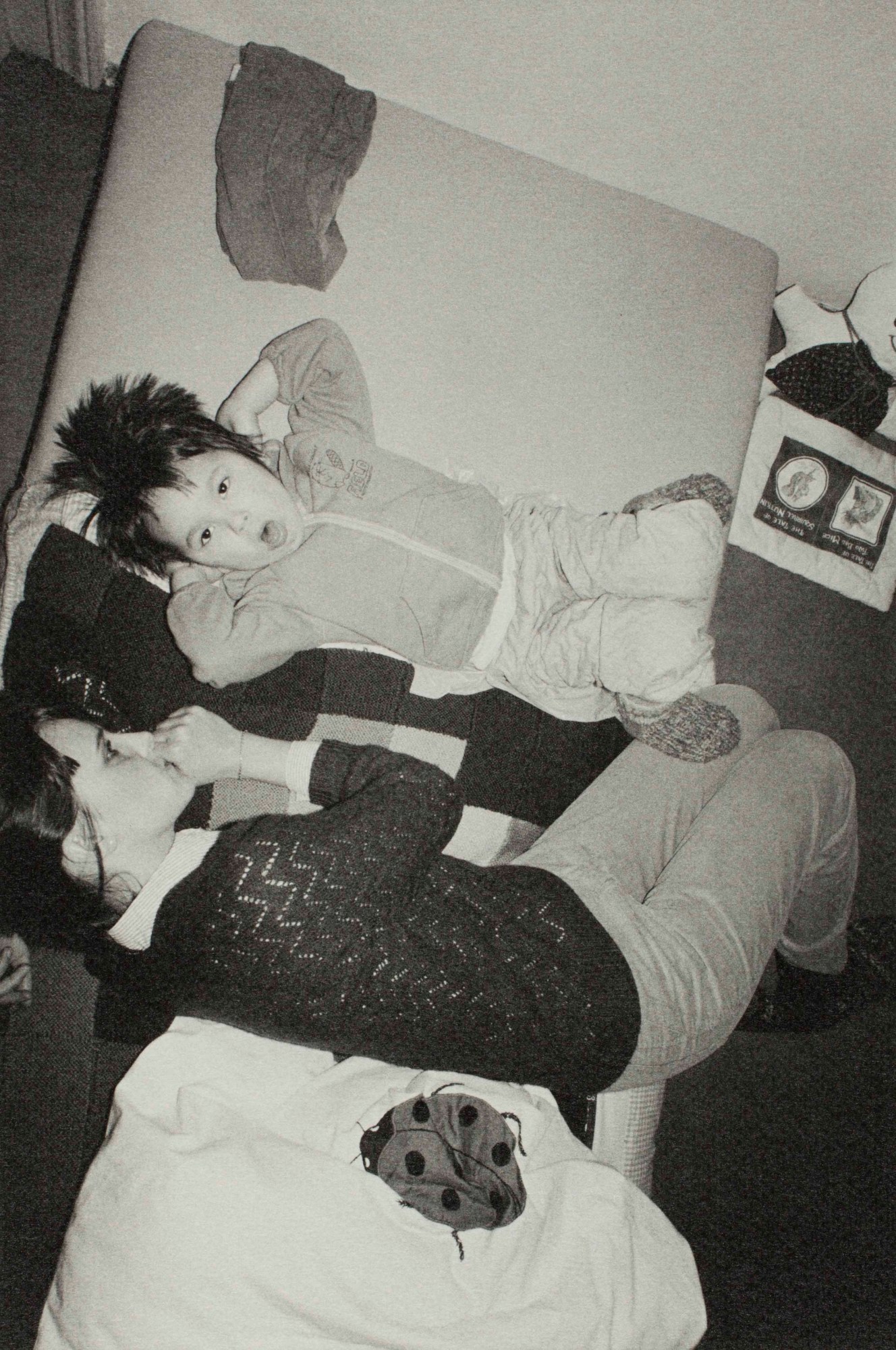

In 1982, Christine told me that she wanted to quit her job and study theatre in Vienna. I was very surprised because I thought she was satisfied at the broadcasting station. At that time, I was travelling to Germany and Japan for various part-time jobs and was away from home a lot of the time. Christine, on the other hand, spent her days taking care of our newborn, Komyo, and working. I am sure she was frustrated, wondering why I was the only one doing what I wanted to do, and she had to do a job she didn’t like while taking care of the kids. I objected to her wish to become an actress because I had a gut feeling that her character, her subtlety, was not suited for the cutthroat world of theatre. But when she told me that becoming an actress had been her dream since childhood, I had no way to argue with her. I believe that she made the decision to follow her own path.

We moved to the 5th district of Vienna. I think Christine left Komyo at kindergarten and went to theatre classes almost every day. I was busy trying to organise a new photography organisation while working part-time as a delivery man for a Japanese food store, but we were still forced to live in poverty. Christine and I had nothing in common in our daily activities. We did not discuss our lives and gradually lost our conversation. Christine took the entrance exam for drama school. I remember Komyo and I going to the place where the successful applicants were announced. Christine’s name was not there. She was in tears. For a moment, I felt sympathy for her, but to be honest, I was glad she did not pass. I thought that she might give up on the idea of becoming an actress.

Was that the end of it?

No. Quite the opposite. Christine became more focused on her classes than ever before. Our relationship fell into an even more disharmonious state, and we sometimes did not speak at all. It was rare for us to ever discuss theatre-related matters, however, I remember her once saying: “I can perform tragedy well, but I can’t perform comedy.”

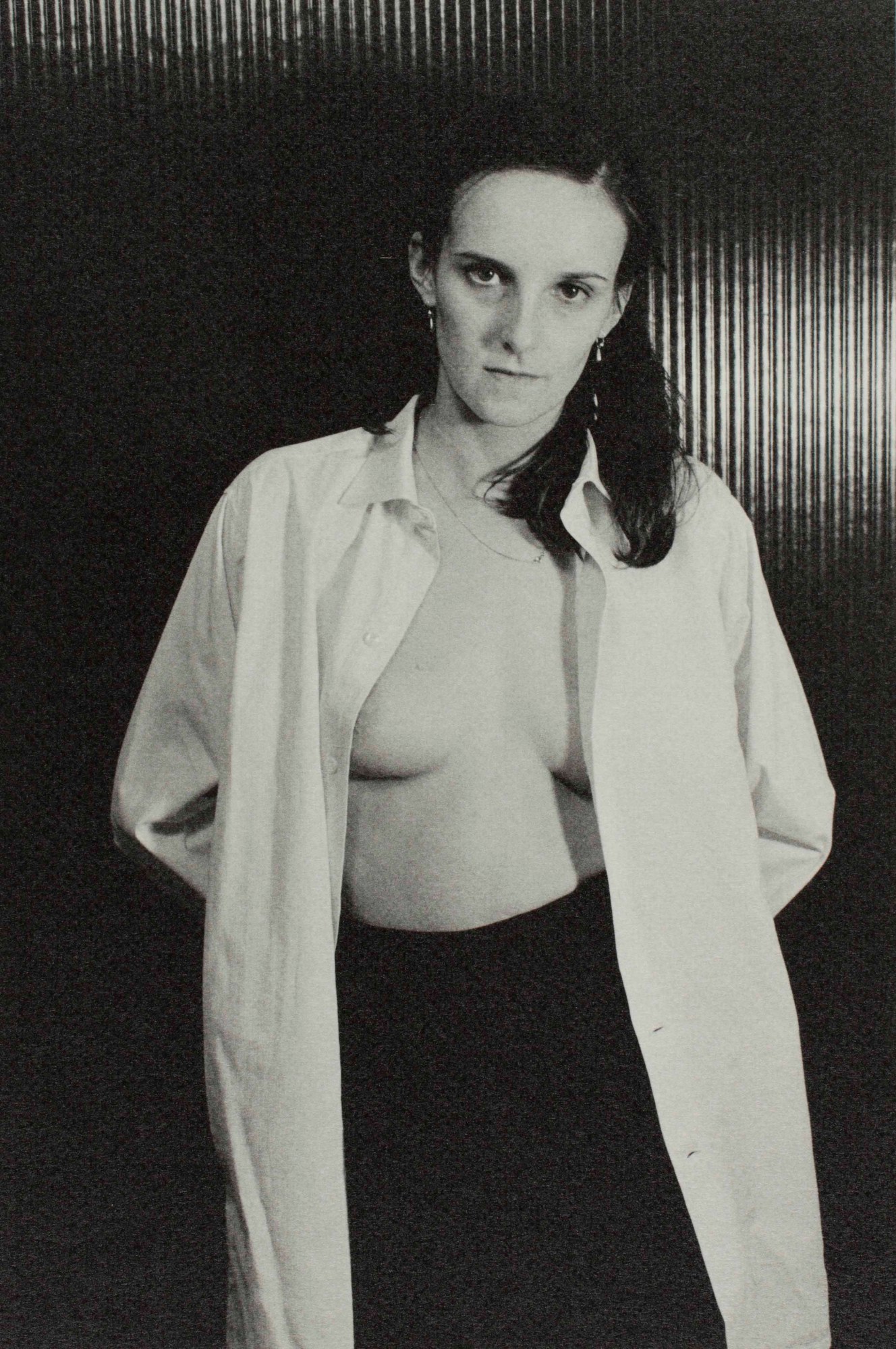

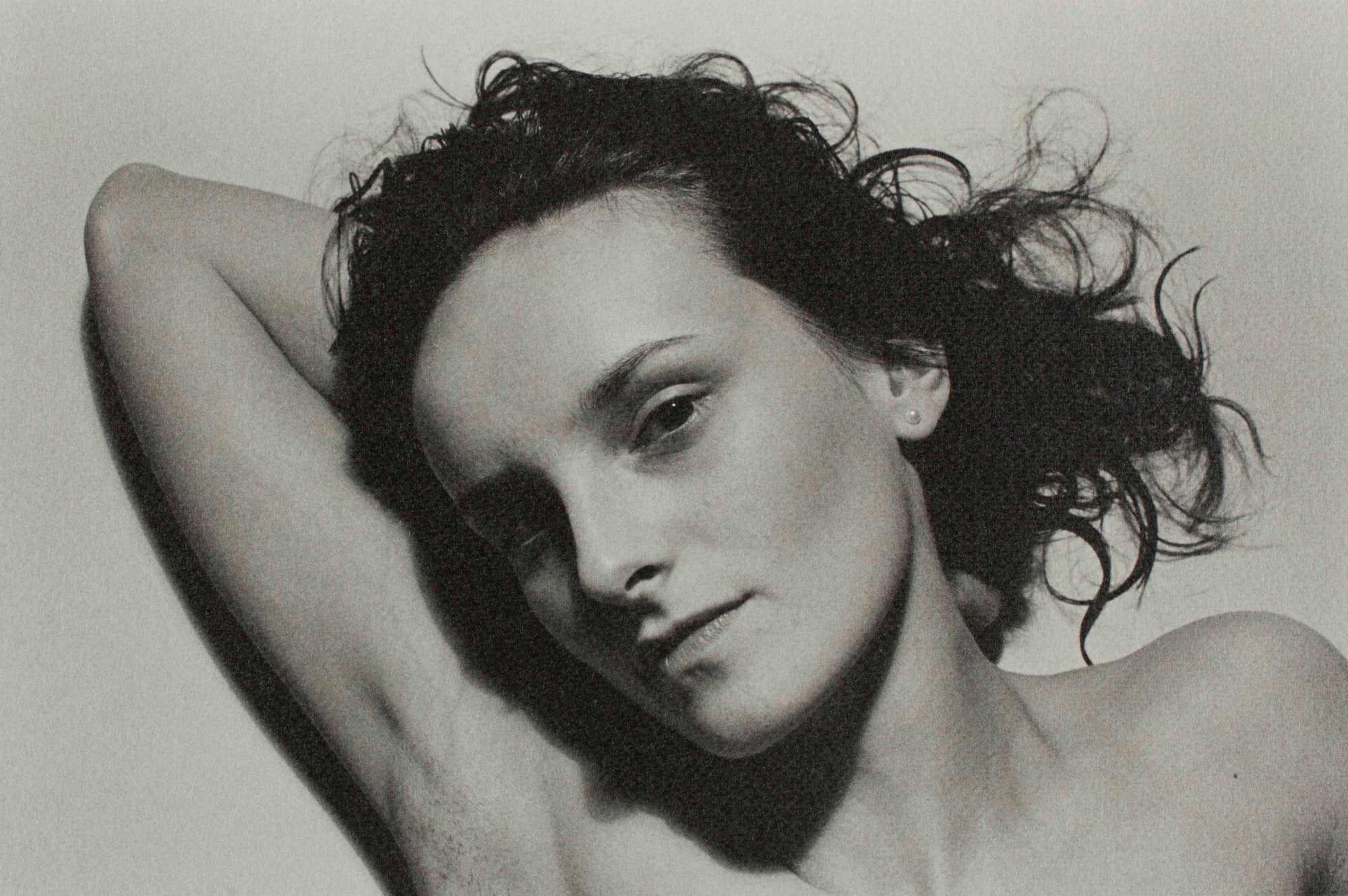

Your photographs have always felt more quotidian than performative.

Never once did Christine ask me to take her photograph. I would suddenly get the urge to point my camera. She would stand still and stare back at me as if time had stopped. It was a momentary lapse, and when I was done shooting, she would resume her activities as if nothing had happened. There was never a moment when I thought Christine was playing any kind of role. Her body movements and facial expressions were just a reflection of her realities. I am still amazed every time I look at her photographs, as if I am being shown her true self. She approaches me with a strong will, as if she is appealing to me for something. I feel as if I am looking at the world of a completely different dimension from the photographs of so-called “models” or trained actors. I believe Christine was an ill-starred actress who, till the very end, played the role she could not become.

Did you ever “go out” for the purpose of photographing Christine?

Only once, in the spring of 1983, after her first experience with inpatient care. We went to Schönbrunn Palace, which was near our apartment and a favourite walking route for the family. I had two cameras, and Christine was dressed all in black, maybe with light makeup. After the shoot, not once did the photographs become our topic of conversation. Christine never once asked to see the photographs I took. And rarely, if ever, did I check the results or print them afterwards. That was unimportant. It was all about sharing a mutual gaze and feeling through photography. That said, the meaning of these photographs changed drastically for me after she passed away. Christine left with a strong final will to take her own life burned into me.

The photographs from 1983 seem to be charged with a heavier, more solemn intensity…

That was the year Christine had her first so-called “seizure”. She stood by the front door and started chanting. It sounded like a spell I had never heard before. She was not supposed to have any connection with the church, but she would not stop repeating words that sounded like Christian teachings over and over again. Two days later, she was hospitalised. 10 days later, she was discharged.

In May 1984, the family moved from Vienna to Dresden. Family life continued to be fulfilling, despite the certain restrictions inherent in East Germany. But around the end of the year, Christine began to behave strangely again. Her condition worsened, and finally, in February 1985, she and Komyo had to return to Graz for treatment. Christine was hospitalised for one month.

Was that when you moved to East Berlin?

Yes. I picked up Christine and Komyo, and we started our life in East Berlin. Christine seemed pleased with her new surroundings. She was actively going shopping, building flower beds in our apartment and seemed to be enjoying the first days of spring. But it didn’t last long. In July, she began showing “signs” of her schizophrenia (as diagnosed by a doctor in Graz) again. In mid-July, she was admitted to hospital. As before, she had refused… “I am healthy, and you are trying to lock me up!” was her usual protest. But there was nothing more I could do.

In those final years, Christine was in and out of hospital repeatedly, but it seems that she never left the “theatre world”. This fact was described in detail in a memoir she left behind on 7 October 1985.

Do you see Mémoires as, at least in part, a way of fulfilling Christine’s ambitions to be on the stage?

Mémoires started not only as a way for me to mourn Christine, but to put my feelings into perspective and create a new start in my life. However, with each new Mémoires, the desire to make her unrealised dream come true grew stronger in my mind. In the end, she never stood before of an audience, and I secretly vowed to make a “stage” through the medium of photography.

I guess the forthcoming book you once told me about – which will compile photographs taken by Christine herself – takes this one step further.

Yes. It will be the first time they are published. This book would not have been possible if the attic had not been cleaned out in 2018.

On a personal level, what has it been like folding your life into this archive — and vice versa — with such intensity?

[So] that I could believe in myself, that I could recognise my personality, that my spirit could coexist with my body, I chose to wander through the world of Mémoires. As my work progressed, I realised how many wrong decisions and actions I had made during the seven years and eight months or so that I had shared with Christine. But it was impossible, at least for me in the immediate aftermath of her death, to look back on my actions. Whether we were happy or miserable, time flew by.

Now, it is not wrong to say that I am glued to the world of Mémoires. It is like an inescapable train station, but by no means unpleasant. If the medium of photography had not existed, and if I had not been able to recall the facts of the past in a truly vivid way, my life, especially after Christine’s death, would have taken a completely different path. I can say that my life has been influenced by the existence of this technology. I cannot help but feel the wonder and horror of the photographic medium.

Your photography has always contained this conflict. It not only lights up a past life but shows how much darkness is around.

All of the photographs are no doubt manifesting a moment in Christine’s past that is walking towards her “ending”. But this fact is, in a sense, undramatic. If it is dramatic, then all of human life is dramatic. All people live towards death. It is a sad fact, but not dramatic.

Christine suddenly disappeared from the world of one family in the form of a “free death”. In turn, she took a piece of my heart. But as her body perished, she left her soul, which has continued to grow inside me over the years. And this soul cannot leave me for as long as I live. When I die, Christine’s soul will also die.

‘Seiichi Furuya: Mother (1982–1985)’ will run at Shadai Gallery, Tokyo from 11 November 2022 to 1 February 2023.

Credits

All images courtesy of Seiichi Furuya.