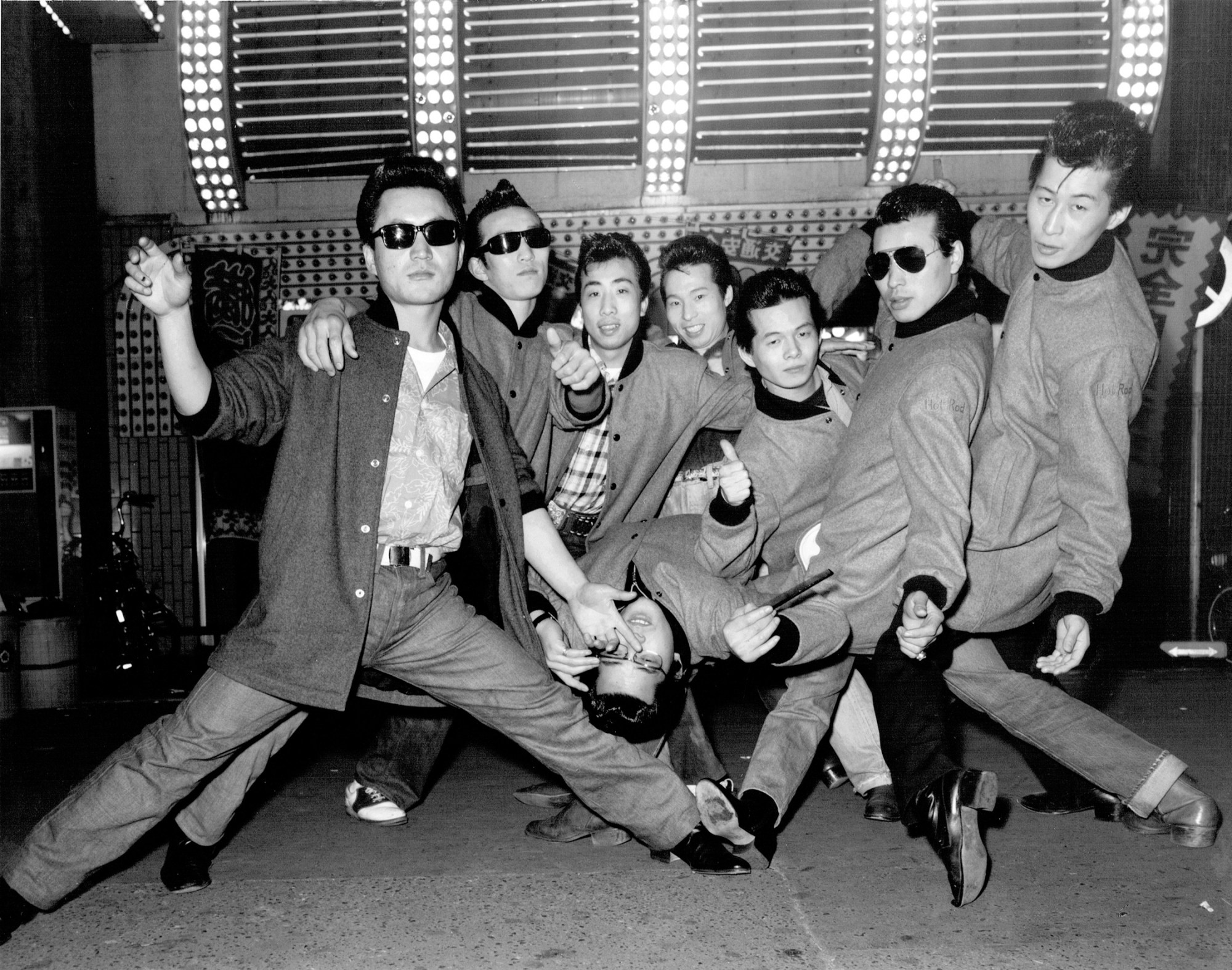

When Seiji Kurata started taking photographs in the 70s, political activism and rebellion against the establishment soaked Japan’s streets, as did the energy and vitality of people seeking freedom and stimulation in a newly stable economy. Dreamers flocked from the countryside to Tokyo, where the entertainment districts that Seiji photographed, like Ikebukuro, were saturated in neon lights, gaudy advertisements and the colourful outfits of people happy to stand out. As he wandered around the nightclub scene of sin city, Seiji became acquainted with a seedy underworld run by the yakuza, and the strippers, cross-dressers and other inhabitants that made up Tokyo’s dark underground.

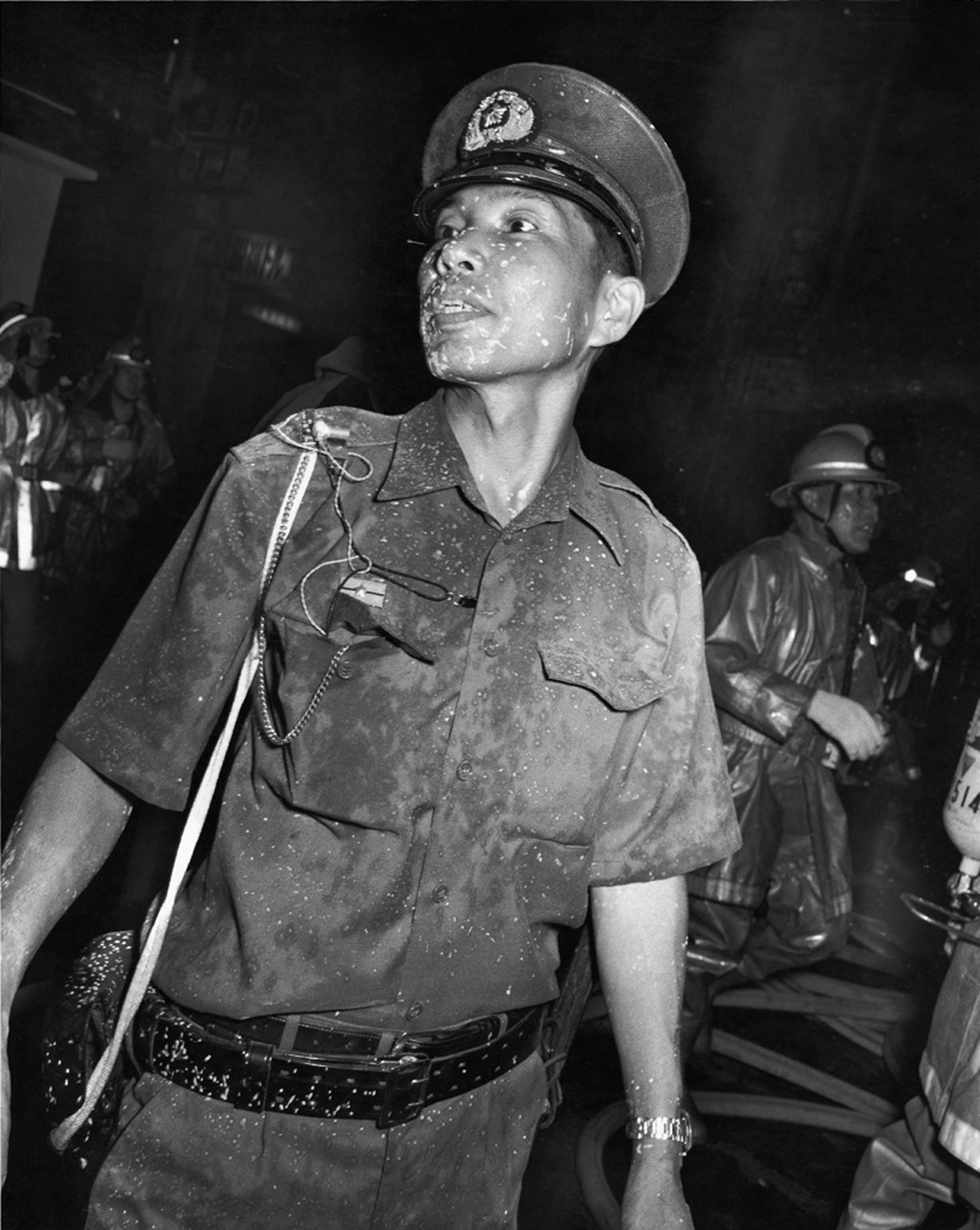

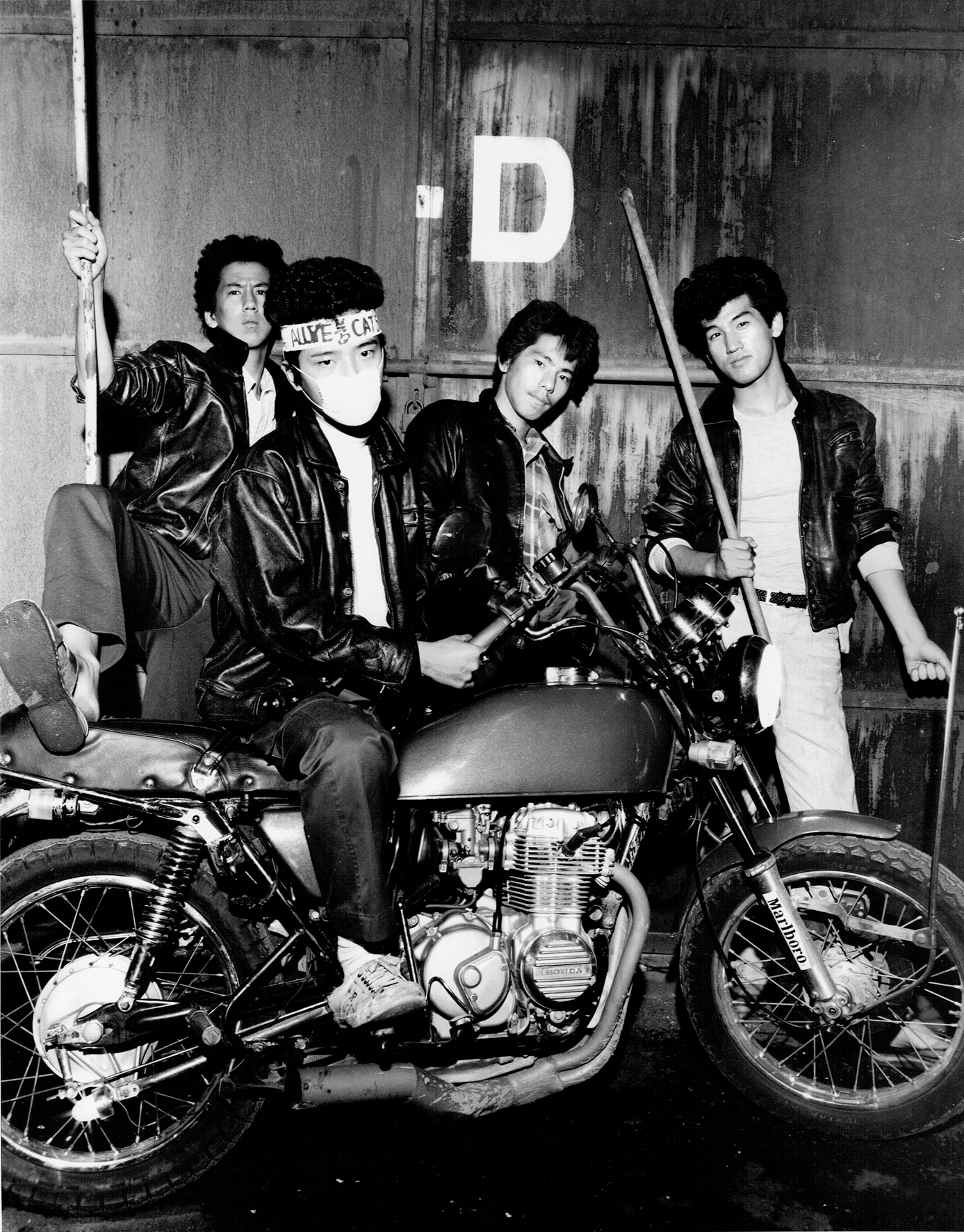

Much of what he captured was violent, such as the fighting between yakuza and motorcycle gangs in Shinjuku that he chronicled with his contemporary, Katsumi Watanabe. Preceding Jake Gyllenhaal’s character in the 2014 neo-noir psychological thriller Nightcrawler, the photographer would intercept the police radio and rush to crime scenes on his motorcycle, take photos of crashes and skirmishes, and then disappear into the night.

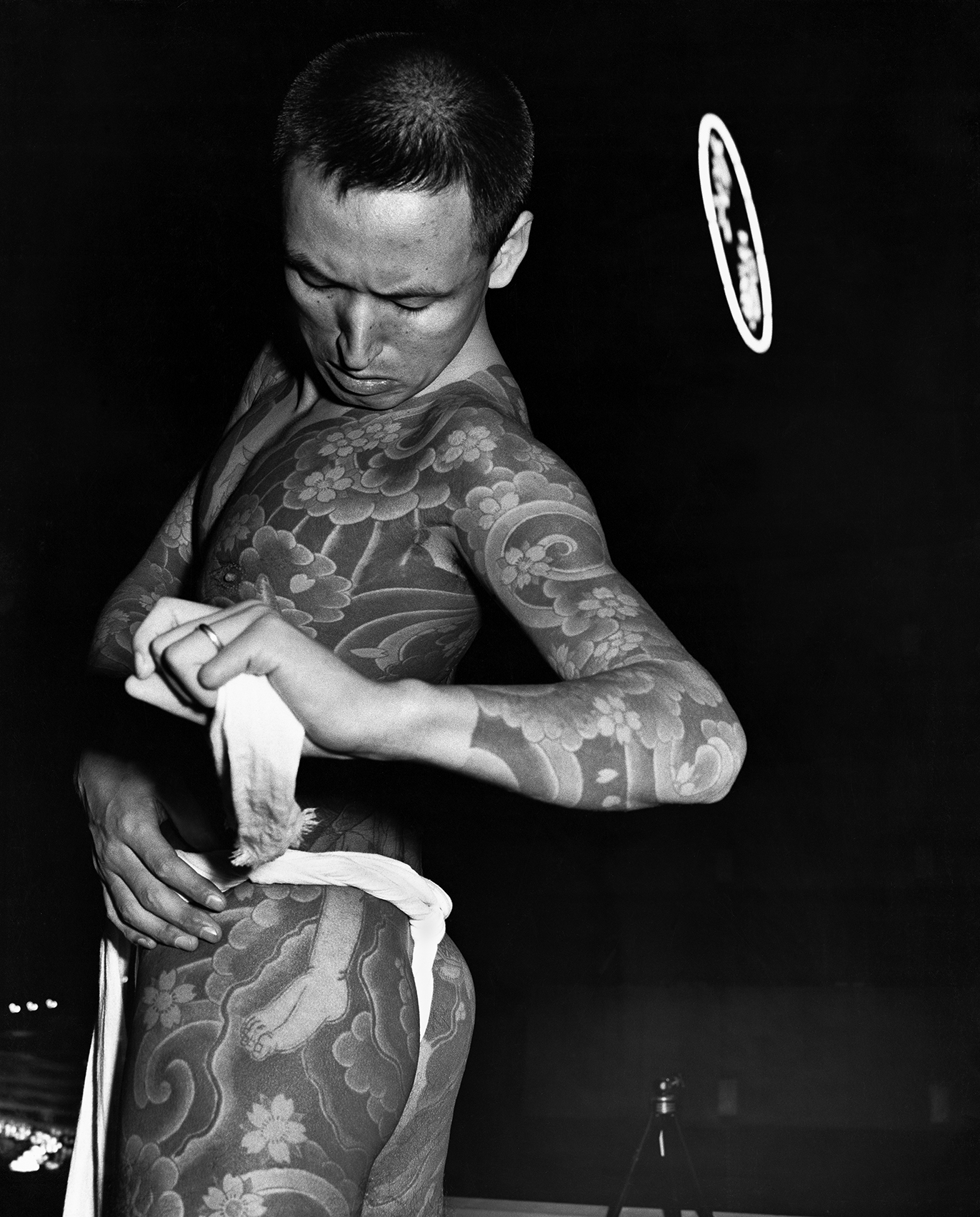

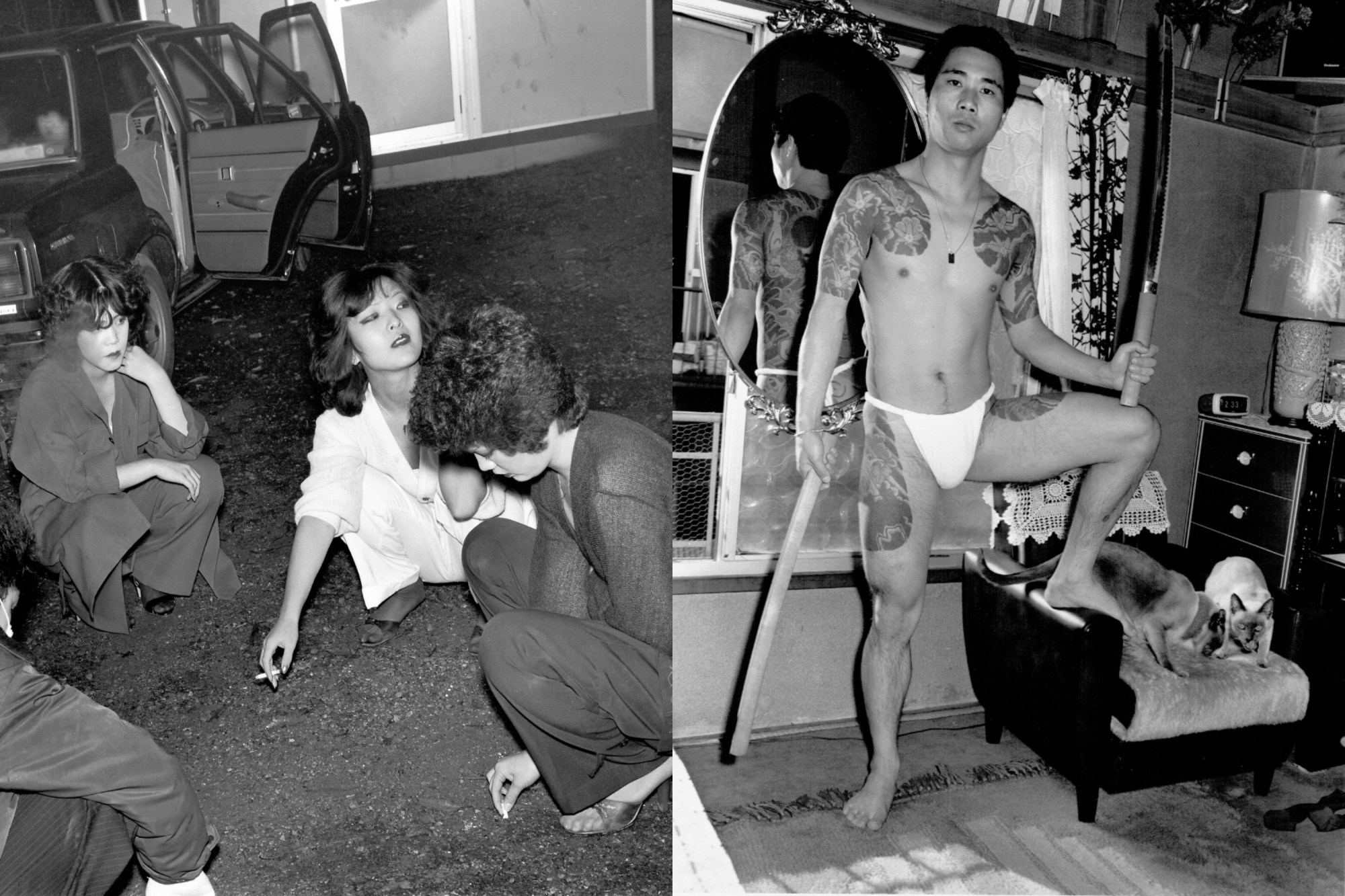

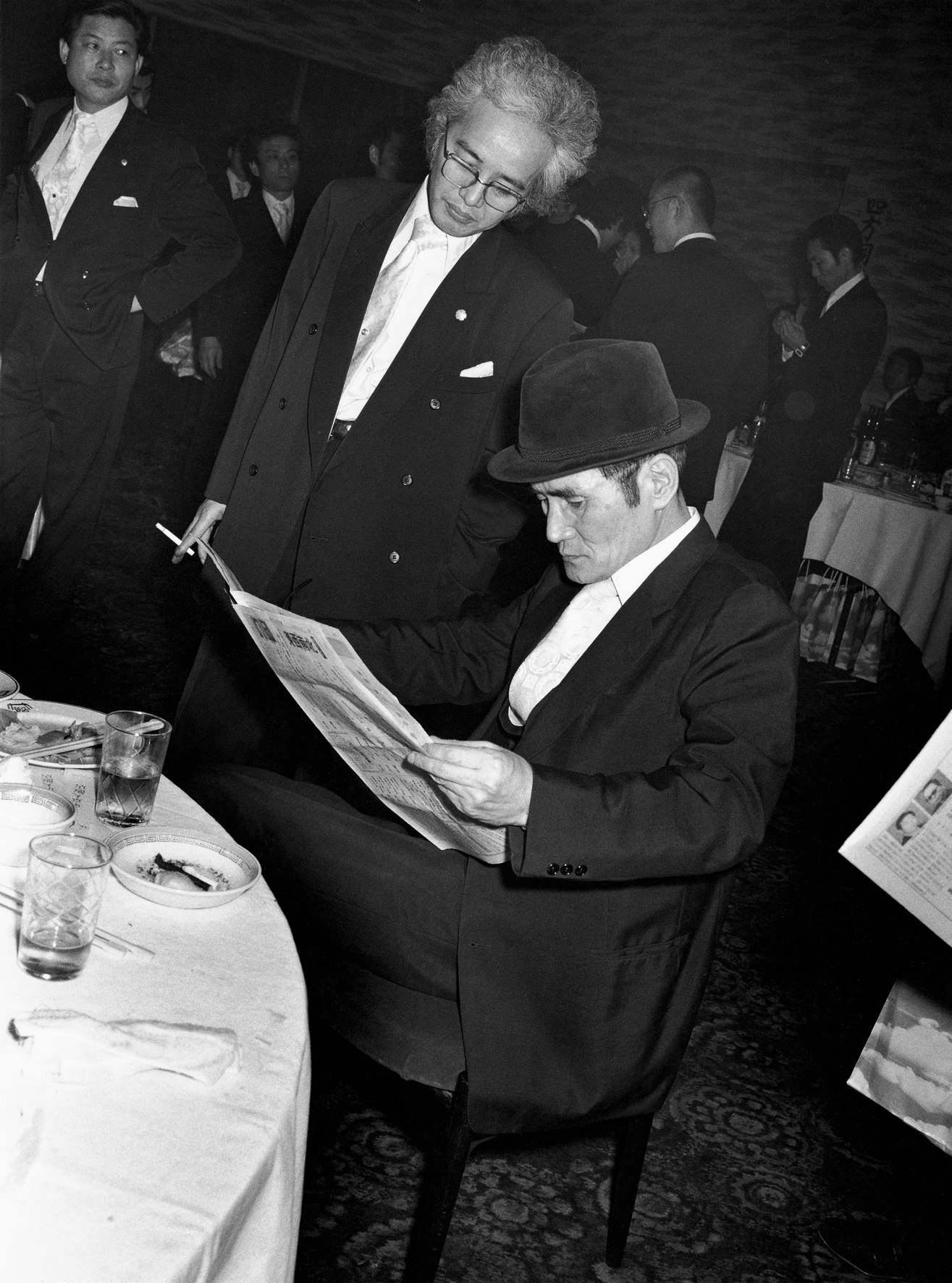

Seiji became famous for his portraits of men gripping samurai swords as long as their tattooed bodies, highlighted by the bright flash of his medium format camera; as well as the cabaret dancers, nightclub hostesses and the horny salarymen groping them for money. These early masterpieces were born “from the perfect combination of these uniquely dressed people desiring to be photographed and Seiji’s desire to take photographs,” says Nina N, who curated two exhibitions, Night, Alleys & People and Lads & Gangs, which are currently on show at Zen Foto Gallery in Tokyo.

In 2013, Seiji recalled an encounter with the yakuza that resulted in his iconic photograph: “The Tattooed Man”. “The town is bright with streetlights, pubs, game centres, cafes, restaurants, arrays of neon and spotlights. Two tall men call out to me. They look and act like playboys,” he writes. “There are no nice landscapes, no skylines or good scenery, and we decide to make the top of a building our studio. On the emergency staircase the two play for ages with their swords like actors in a samurai film and tell me to make them look like [the actor] Ken Takakura. They also tell me to show them all the photos taken, and to make big prints of any that are good.”

Seiji captured these subjects intimately, finding glimmers of humanity in everyone from the yakuza and Bosozoku to the ultra-right wingers at Shibuya’s Meiji Jingu shrine. He would often take the photographs in gangsters’ homes, with cats playing in the background and gilded mirrors softening an otherwise aggressive image. Or he’d wait until two sex workers began laughing hysterically before clicking his camera. Outside a cabaret, he captured a tired mother taking a break as her child plays in front of her place of work. “[Ikebukuro] is a town where you can feel the unrefined atmosphere of human sympathy, rather than the stinging stimulation of a cutting-edge town like Shinjuku,” explains Nina, of the district in which Seiji worked.

Developing futuristic tendencies with the advent of new technologies, post-occupation Tokyo was finding its feet as a leading Asian city — and Seiji was captivated by its people. “Living in Tokyo is a journey. Can there be any city that has such transformations?” he wrote in 1980.

“My life’s journey began in this city, if perhaps a little late,” he said about his decision to leave the small thermostat factory in which he worked to pursue a career in photography at the age of 30. “One day when I was not so young, at a time when my sense of reality had been progressively diluted and anaesthetised, I fell into a state in which my reality was dilapidated and ruin inevitable. At the time, I was earnestly seeking the medium for my expression, but had not yet found the answer.”

He had seen some photographs in a magazine by Daidō Moriyama, a street photographer known for his confrontational images showing the contrast between traditional values and modern society in postwar Japan, and the darker aspects of urban life. Soon after, he signed up as one of the first students of the Workshop Photography School, featuring faculty photographers: Daidō, Eikoh Hosoe, Masahisa Fukase, Nobuyoshi Araki, Noriaki Yokosuka and Shōmei Tōmatsu.

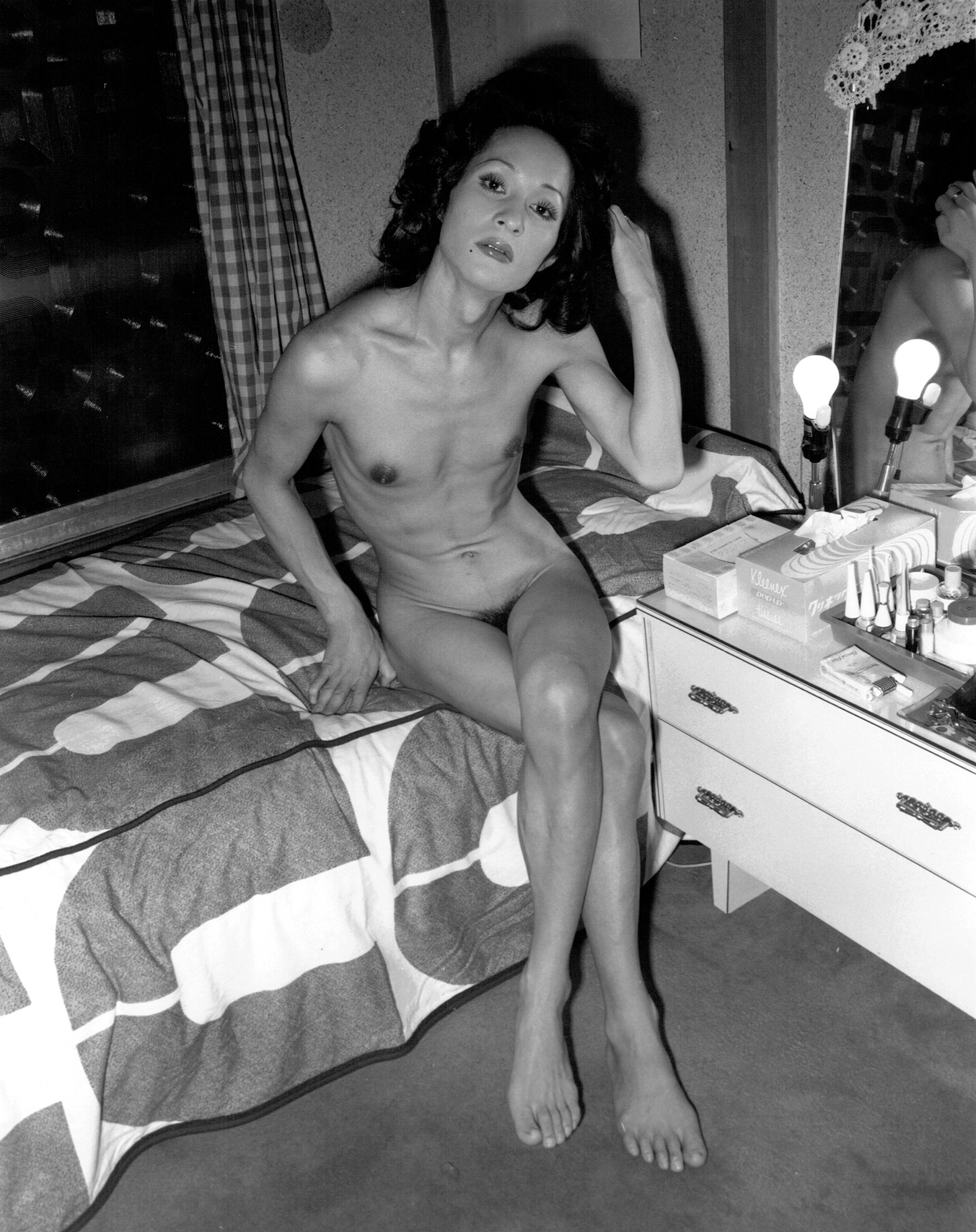

Seiji won the fifth Kimura Ihei Award in 1980 for his first photo book, Flash Up, which explored the seedy streets of north-western Tokyo at night, much like his mentor Daido. But as the years went on he retreated indoors and captured nudity and erotica like Araki — whose controversial and explicit photographs of women in Geisha costuming bound in Japanese bondage kinbaku sought to provoke. What was different about Seiji’s work, though, was the active part his sitters played in his images. In Eros Lost, Seiji experimented with the human body, sculpting portraits of men and women in conjunction with mechanical installations, theatrical performances, objects and vibrant interiors. Depicting a dynamism of nudity, motion and avidity.

The same is true of the trans women and crossdressers he photographed. Seiji explored nudity with care and respect to his subjects, and seemed to get on with the people he captured. According to his wife, Seiji was very fond of Mary of Utsunomiya, and even included a heart and the onomatopoeic word for kiss, “chu,” in one of these portraits.

“With an insatiable spirit of inquiry, [Seiji] was constantly exploring the possibilities of photography using a variety of techniques in different subjects,” Nina says. In 1978, Seiji held his first solo exhibition: Night Dwellers, and in the accompanying publication he wrote: “What I want to do is to observe them. I want to see as many persons as possible, as precisely as possible. It is a must to keep tight the surface tension of the world.”