One of the earliest lessons we learn as children is that when we do something wrong, we should apologise. However, what your parents don’t tell you, is how complicated this can become in adulthood, especially when it comes to relationships. In fact, as we get older, saying sorry has the potential to cause the opposite of its intended effect — it can open old wounds, bring back traumatic memories and, ultimately, stand in the way of someone healing rather than helping them do so. If it’s taken someone years to realise they owe an apology to an old partner, friend or relative, or simply muster up the strength to offer them one, then contacting them out-of-the-blue is not a straightforwardly moral act.

Out-of-the-blue apologies have a real potential to backfire. I often see people complaining on social media about their childhood bully contacting them to say sorry for something anodyne, as though the apology was an entirely rude and selfish thing to do. On the one hand, this is an understandable reaction to being reminded, unilaterally and without your agreement, of a painful experience. But if the apology appears to be sincere and in good faith, as they often do, it does strike me as a little ungracious to screenshot it and post it on the internet with a caption like ‘can you believe this bitch?’

It’s also important to consider that, quite a lot of the time, when someone reaches out to make amends to someone they hurt in the past, they are often doing it as part of some kind of therapeutic programme — Alcoholics Anonymous or any 12-step recovery programme being the most common example. If someone contacts us to apologise because they’re trying to recover from an addiction, I think we have at least some obligation to respond with good grace, although it depends on the severity of the transgression. Apart from anything, forgiving someone and the smug “being a better person” satisfaction that might come with it, can feel really good. If someone contacts you to apologise, I think in most cases, it’s better to err on the side of graciousness.

People taking part in 12-step programmes are encouraged only to contact someone to make amends if doing so won’t cause the recipient further harm. This is a solid principle to abide by, whether you’re in recovery or not. If you’re certain that your ex, former friend or whoever, won’t want to hear from you, then it’s better to leave it. But the problem is, it can be difficult to tell in advance how an apology will go down. Some cases are clear-cut: if I slept with your boyfriend last month and you’ve asked me not to contact you, I can be reasonably confident that keeping my distance is the right thing to do. But what if my behaviour was less tied to one particular hurtful incident and instead constituted more insidious behaviour over months or years? Contacting them might dredge up painful memories, but on the other hand, they might be glad of an apology. If we weigh up whether to say sorry to someone, and we’re unsure how they’ll react, is it better to err on the side of caution and not bother? Or is it better to roll the dice and risk causing further pain?

“People taking part in 12-step programmes are encouraged only to contact someone to make amends if doing so won’t cause the recipient further harm. This is a solid principle to abide by, whether you’re in recovery or not.”

According to Dr Harriet Lerner, a psychologist and the author of Why Won’t You Apologise?: Healing Big Betrayal and Everyday Hurts, clear thinking and intuition can go a long way in deciding whether an out-of-the-blue apology is a good idea. “If I were to generalise,” she says, “I would err on the side of apologising for past harm if it’s a key relationship: your mother, daughter, sister or Uncle Charlie. I would err on the side of not apologising for past harm if the relationship is over, it’s not an essential connection, and there is no reason to believe that the person wants to hear from you. Cruelty for someone in high school might well go in this category, although if you’re still in contact with that person (say you’ve been thrown together in a work project), you might say something like, ‘You know, I was a total jerk to you back in high school. I was so insecure in myself that I took it out on you, and there’s no excuse for that.’ No more than that unless the person you’re apologising to wants to continue the conversation.”

A lengthy, waffling, self-indulgent message ceases to be about them and brings everything back to you. “If you’re not sure your apology is welcome, keep it short!” Dr Lerner says. “If you go on too long, explanations will turn into excuses, and heavy, sombre tones can deepen the original injury. Brevity is essential. And remember that the purpose of an apology is to facilitate the other person’s healing and sense of well-being, not to foster your own recovery or lower your guilt quotient.”

For that reason, when you apologise to someone, it’s better not to expect anything back. You can’t demand forgiveness, nor can you depend on anyone else to make you feel better about your own mistakes. If you genuinely want to admit a wrong and take responsibility for your actions, then you shouldn’t expect the wronged party to respond in a particular way or even respond at all. No matter how graciously someone forgives you, they cannot absolve you of your own guilt. You might feel better for having been forgiven, but the responsibility for your own emotions ultimately lies with you. So if you are thinking of contacting someone to apologise, be prepared for them to get agitated or ignore you — but a response like this doesn’t preclude the possibility of you forgiving yourself. There can be a personal dignity in owning up to a mistake, even if the result it yields is not what you’d hoped for.

When Ella (26) reached out to a former friend — let’s call her Gina — to apologise, it went about as badly as possible. Years before, they’d had a fraught, ambiguous friendship that veered between being sexual and platonic. “Our relationship was largely predicated on her giving me MDMA, which after a point I realised wasn’t healthy,” Ella says. Instead of raising her concerns with Gina, Ella ghosted her. For Gina, it was upsetting to lose such an intense relationship with no warning or explanation. Years later, when Ella decided to contact Gina to apologise, after spending time in AA, Gina replied, “thank you for the apology but you were an absolute dickhead. I don’t forgive you and also don’t contact me again”. As Ella sees it, this was somewhat ungracious. “It was more of a toxic dynamic which involved us both, rather than me being cruel to her,” she says. But despite the fact that Gina refused to forgive her, Ella is still glad that she reached out. “I don’t regret it at all,” she says, “because I did behave less well than I should have. I obviously felt aggrieved that she told me to fuck off, but I still think it was the right thing to do.”

“If you are thinking of contacting someone to apologise, be prepared for them to get agitated or ignore you — but a response like this doesn’t preclude the possibility of you forgiving yourself. There can be a personal dignity in owning up to a mistake.”

Rather than anger or gratitude, sometimes the reaction to an unsolicited apology will be straight-up bemusement. This was the response someone we’ll call Gordon (22) got when someone messaged him on Facebook to say sorry for “talking shit and spreading rumours” about him back in high school. At first, Gordon had no idea who this person was, nor any memory of the behaviour in question. After a while, the penny finally dropped — it was his English teacher. “He wasn’t even my English teacher,” says Gordon. “I honestly just found it very funny — he felt compelled to send me this apology years later, and it took me half an hour to remember who he was.” This teacher arguably needs to be struck off some kind of register, but tracking down Gordon to apologise for gossip spread in the teachers’ lounge was nonetheless a little extra. Before reaching out to apologise to someone, it’s worth asking whether you’re overdoing it.

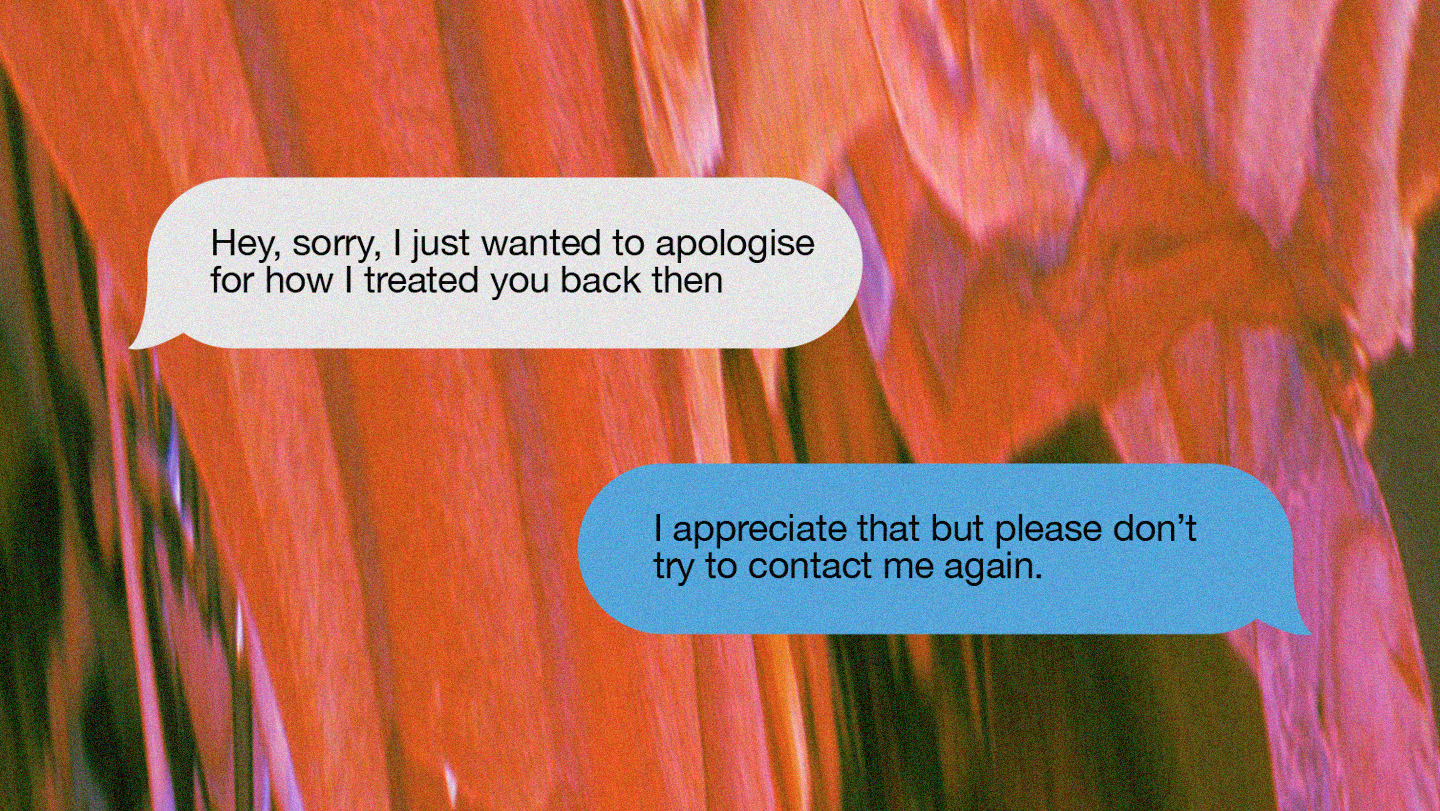

One time a guy I’d been involved with who’d treated me somewhat, but not dramatically, badly contacted me on Christmas Eve to apologise. He had messed me around to an extent, but mostly he’d hurt me by ending our not-quite relationship, which is hardly the crime of the century. Despite this, I was not at all happy to hear from him. It had taken me a while to get over him, and hearing from him threatened to undo whatever progress I’d made. So I replied, “please don’t contact me again,” and blocked his number. This was arguably a reasonable boundary to assert, but it was also, I realised later, an attempt at punishing him.

“Refusing to speak to someone without terms for repair is a strange, childish act of destruction in which nothing can be won,” writes Sarah Schulman in Conflict Is Not Abuse. “Like all withholding, it comes from a state of rage… by refusing to talk without terms, a person is refusing to learn about themselves and thereby refusing to have a better life.” I happened to read this book a little while later and realised that I had been ungracious: in seeking to protect my own feelings, I’d behaved cruelly towards someone who had reached out to me in good faith. I got back in touch with him and apologised for not accepting his apology; he accepted, and we had a brief, polite conversation before never speaking to each other again. While it didn’t lead to a reconciliation (there wasn’t really anything to reconcile), it did come as a relief to relinquish whatever resentment I’d had about the situation. I’ve realised that it’s always better not to have beef with people wherever possible, which is a solid basis for both apologising and forgiving. But the behaviour for which he was apologising wasn’t that deep, and it was reasonable of him to expect that I wouldn’t be traumatised to hear from him.

Which brings us to a final question: if there’s zero ambiguity and you know with certainty that someone to whom you owe an apology doesn’t want to hear from you, what should you do? The concept of ‘living amends’, also taken from AA, might be helpful here. Living amends is partly about leading a sober life, but you don’t need to be in recovery to find it useful — it has elements that we can all put into practice in our everyday lives. It’s about making it up to people you’ve hurt in the past, through actions rather than words. Where it’s not appropriate to contact someone, living amends can take a more expansive form: trying to change your behaviour for the better in the broadest possible sense. If you cheated on an ex-partner or otherwise treated them badly, you can endeavour to be more considerate in future relationships. If you bullied someone in school and feel bad about it, you can make a conscious effort to be kinder to people going forward or, say, raise money for an anti-bullying charity. Living amends isn’t a way of undoing past harms (although neither is an apology) and the person you harmed might never even hear about how you’ve changed, let alone benefit from it personally. But it can be a way of living with and forgiving yourself – which could well be the absolution that you’re looking for the most.