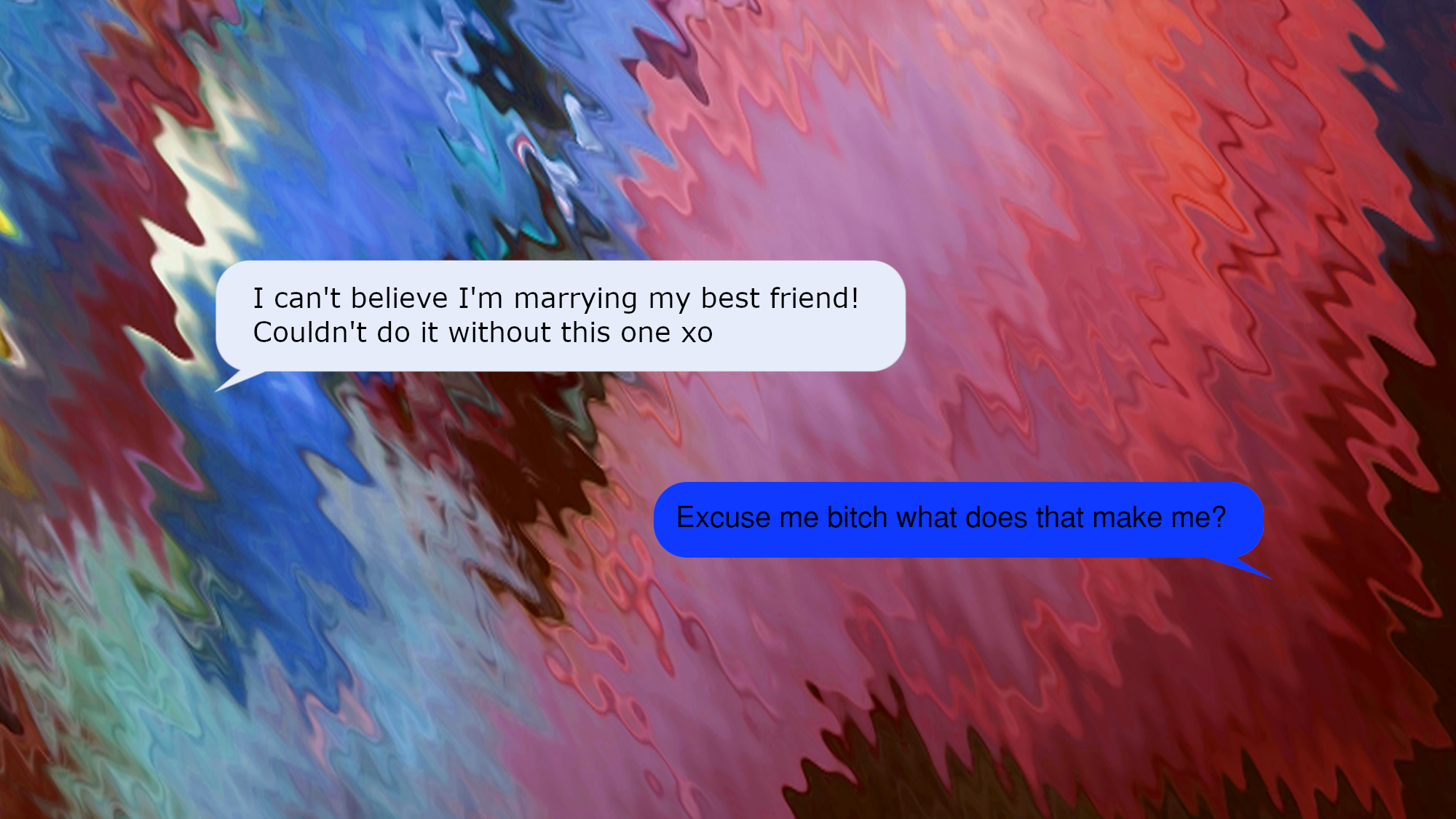

Like it or not, we end up submitting a great deal of our lives into the yawning chasm of the internet. Our breakfasts and our holidays, the milieu of our jobs, our opinions and our outfits all get uploaded for assessment on social media. We pour our lives onto the grid and talk about things in particular ways online, using brain-poisoned phrases and terminology that might raise more than a few eyebrows if overheard at the pub. But there are few subject areas more complicated to navigate online than our own romantic relationships. From “this one” to “favourite human” to the delicate art of the soft launch, we have invented entire paradigms to talk about our partners on the internet. One trope stands out from the rest as particularly unavoidable: variations on “best friend”, as in, “I am so pleased to be marrying my—”.

How we choose to describe the people we care about most is undeniably important: there’s as much in a nickname as there is in a name, and how we use them to frame those relationships can tell us a lot about our expectations within them. I am personally not a fan of the “best friend” trope, most often employed by women in heterosexual relationships. My close friends are enormously important to me, but painting a romantic partner with the same brush as their platonic equivalents seems like an oversight, or at least a path to overburdening that particular relationship – it’s not fair to expect a partner to address the sum total of one’s emotional needs.

To call someone a best or close friend is meaningful and distinct, a discrete and special category established over time and through mutual experiences. While it can certainly be applicable in some cases, it shouldn’t just be a superlative to throw at a romantic partner – an already extremely socially-validated form of relationship. To take an admittedly harsh view, best friendship also implies equal partnership and respect – something that has not, historically, been a characteristic in heterosexual marriage and relationships.

Maggie Kalenak, a historian of romantic culture completing her PhD at the University of Cambridge, explains that the ideal of the “companionate marriage” – which she describes as “the idea that affection and romantic love should be valued in marriage” – isn’t new, though it hasn’t been around all that long. This social more emerged in the 19th century: previously, marriage had been seen to be based more around family allegiance and inheritance. Our idea of an ideal marriage became more companionate into the 20th century, as women gained greater freedom and cultural agency: freedom to work, own property, vote, and generally take part in public life.

For Sara, a 24-year-old in the 21st century, calling her partner her best friend – in public or in private – is an acknowledgement of how comfortable they are together. “It means they are someone who I can share everything with without fear of judgement”, she says. “My best friend outside of my partner has always been my biggest advocate and my partner is the same! So it would feel a little odd not to class them as a best friend too”. Rob, another supporter of the trend, feels similarly: “To me, [my partner] is someone whom I can share anything with, without hesitation and without fear of judgement”.

Not everyone favours the romantic “best friend”, however. “I sometimes talk about my fiancée on the internet”, says James (25). “I’m happy to describe her with all kinds of superlatives, but not ‘my best friend’. I guess in some ways she is, but I feel that they’re separate categories. We aren’t just friends – I love her in a very different way to how I love my friends. It does both her, and, I guess, friendship, a disservice to pretend otherwise. I’m comfortable with her in a very different way to how I am with my friends”.

Maggie Kalenak’s suspicion is that women who best-friend-post their partners are also trying to signal that the object of their affections is fundamentally a Good Guy. Describing your partner as your best friend confers some of the implied consistency and stability onto the relationship. It is also understood as a “green flag” for a man to have female friends. Culturally, we also hold onto the idea of friendship as being more calm and more consistent than romance; you might change partners, date around, but your friends will supposedly always have your back. This also explains why we have endless social scripts for breakups (“it’s not you, it’s me”; “we grew apart”; “we realised we wanted different things”) and few, if any, for the dissolution of friendships. Love is famously conceptualised as “friendship set on fire”, which is all well and good if you skip over the implication that your partnership may now be a burning wreck.

On a fundamental level, speaking about your romantic endeavours online is inevitably quite cringe. Though it’s “unavoidably ew”, 28-year-old Alice overcomes cringe every time she admits her partner really is just her best friend; “He’d be my first choice of person to spend time with in most scenarios I can think of.” But cringe may well be the keynote feeling of the human experience: what we deem cringe is often simply sincerity, which sits ill in our based and irony-pilled times. Your partner and your best friend may well be one in the same – far be it for me to judge how friendless it makes you seem. Kidding! We have all rolled our eyes at the saccharine posts of the too-online couples we know and thus are subjected to; better, though, to be sincere, cringe, and free.