“Nowadays, everybody in Tokyo looks so boring,” sighs Comi, co-founder of underground Tokyo brandMYOB. We’re sitting in a Harajuku cafe with Comi’s design partner Tanimi, and their store manager Eno, discussing the recent decline of style in Japan’s capital. “Two, three years ago, everybody dressed stronger, more fashionable, more colorful. Today…” Comi waves her hand disparagingly, gesturing out of the window to the passing crowd. She has a point. The color palette on the street is a sensible spread of camel, navy, and grey, punctuated by the odd Breton stripe. It’s tasteful of course, and fabrics are notably high quality (Japan is still Japan), but there is little of the aggressive, vibrant aesthetic that earned Tokyo its rep as an international fashion capital. Of course the city still retains its fair share of trendsetters, but like Japan’s birthrate, they seem to be dwindling.

An acronym for Mind Your Own Business, MYOB is one Japanese brand challenging the city’s normcore complex, and offers Tokyoites an alternative to the increasingly ubiquitous mundanity on the streets. Founded by friends Comi and Tanimi after a stint spent living in New York and inspired by the vibrant attitude towards style they found there, the duo launched MYOB in Tokyo in 2014. Since then, the brand has rapidly reached cult status among Tokyo’s youth for its uniquely modern aesthetic, which Comi describes as “gothic, sporty, punk streetwear.” Its monochrome boutique in Harajuku’s La Foret department store is like an angrier, creepier Y-3, framed by a guttural soundtrack of hardcore techno and hip-hop. There’s an obvious nod towards health goth, but upgraded for 2016, with a heavy dose of teen angst and a palpably clinical edge.

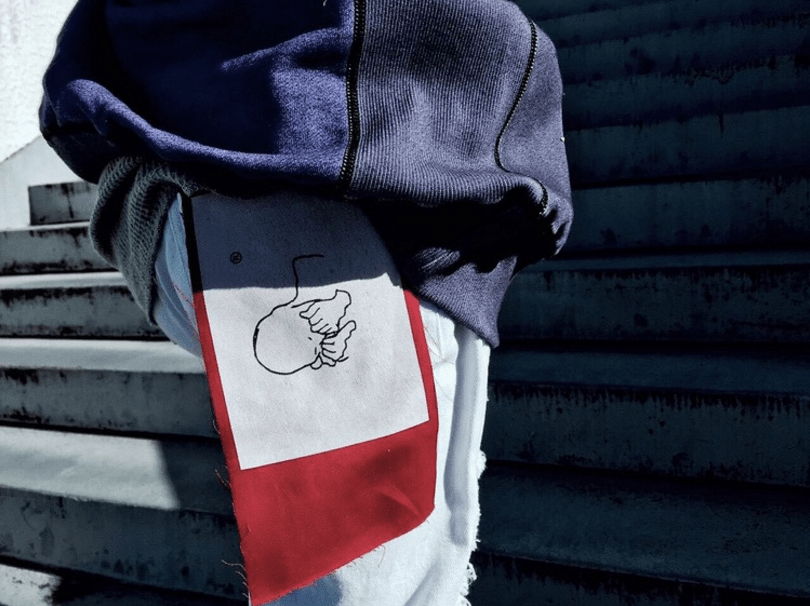

That clinical edge is literal — it’s worth mentioning that Tanimi was a nurse before founding MYOB, and store manager Eno recently did some art direction for a fashion-forward dental clinic. Unsurprisingly, medical connotations pulse through the brand’s aesthetic like veins. An off-white cotton shirt reminiscent of a straitjacket has a disconcerting photograph printed onto its front of a sign reading ‘DEATH ROW’; another t-shirt features a picture of a man being resuscitated. A pair of black denim sweatpants are slashed razor-style across the thighs, a patch on the backside depicting a line drawing of a sobbing figure. In a culture where mental health is considered a taboo topic for many, MYOB’s dark, evocative imagery is especially jarring. Nevertheless, the designers’ motivations aren’t as morbid as you might expect: “I drew that picture of a sad guy [on the sweatpants] to show that it’s okay to cry,” Eno laughs, alluding to how difficult it can be to express emotions in Japanese society (one of her other designs features an image of a boiled egg cut in half, captioned with ‘boiled ego’, a play on the Japanese accent, and referencing the need to liberate our ego rather than hide it away — deep stuff for an egg-print t-shirt). As for the death row photograph, Comi chose it after being inspired by hip-hop references about prison in Snoop Dogg’s music. “It’s not that dark to me — I just took it from the music. It’s more like ‘yo, death row!'” she laughs from behind her sunglasses, crossing her arms in a mock rap gesture.

Despite MYOB’s innocent intentions, referencing physical or mental illness on clothing is an internet-age minefield. In 2014, Urban Outfitters found itself in hot water for stocking a black and white t-shirt covered with the word ‘depression,’ and was accused of glamorizing and capitalizing on mental illness. Comi is quick to defend MYOB’s design decisions, citing an organic referencing of personal emotions and artistic collaboration, as opposed to any calculated bandwagon-jumping: “our design is inspired by our feelings and our everyday private lives.”

Even so, the feelings that inspire the brand signal a darker, creepier undertone currently happening on Tokyo’s street scene, and point to a wider fashion trend for medical references which include more than just souped-up surgical masks. If Japan’s pioneering beauty trend last year washing over make-up, in 2016 it’s more of a morphine comedown. Recent beauty looks on a string of Japanese Instagram stars feature feverishly dewy skin, red puffy eyes, and a quarantine-worthy pallor. The kawaii influence of Harajuku’s past is also being given a sinister makeover: Nesinis a relatively obscure brand based in Shibuya, selling oversized vaporwave-print tees emblazoned with hand-painted kanji characters referencing god, death, the internet, and death to the internet. The despondent characters set against a saccharine aesthetic creates an effect that is simultaneously disturbing and infantile: yami-kawaii, (translated as “sick-cute” in Japanese), defines the growing fashion for tearing apart the pastel perception of kawaii style, and rewriting it as something altogether harsher and unnerving, explicitly referencing disease, pain, and depression, all with a honeyed Harajuku undertone.

The uncomfortable trend for referencing emotional negativity is no coincidence, and chimes with a particularly difficult time in Tokyo. “In Japan right now, the quality of life is at a very low level,” says Tanimi. At first I’m taken by surprise — with its efficient transport system, revered work ethic, and automatic toilets, Japan seems practically utopian at a glance — but the country is adroit at putting on a brave face. “People work a lot and they don’t sleep; they’re too stressed.” In a place noted for its punishingly long working hours and a growing mental health crisis, the pressure that most Tokyoites find themselves under mean they often have more to worry about than their wardrobes — last year, compensation claims for mental illness and suicide caused by overwork rose to a record high. “It’s difficult to have fun in Japan because everybody has so many responsibilities,” says Tami.

Still, even if Tokyo’s enduring taste for normcore currently permeates the mainstream, the brands dominating Tokyo’s experimental fashionscape potentially signal a more open, emotional Japan. And if that sounds reaching, it seems, at the very least, like Tokyo is getting its fashion mojo back. Despite the recent proclivity for appearing as though you’re on your deathbed and all the references to being unwell, this is the healthiest the Japanese underground has looked for ages.

Credits

Text Ashley Clarke

Images via myob-nyc-shop.com