In 1988, at the age of 14, Slava Mogutin left his native Siberia and moved to Moscow. By 1994, at the age of 20, he was attempting to register the first same-sex marriage in Russia. As a writer, photographer and activist, he made a name for himself by challenging prejudices around homosexuality in Russia. The authorities were less than appreciative of his work though. He was accused of “malicious hooliganism with exceptional cynicism and extreme insolence” and faced time behind bars when, at the age of 21, Slava left for New York, becoming the first Russian to be granted political asylum in the USA on the grounds of homophobic persecution.

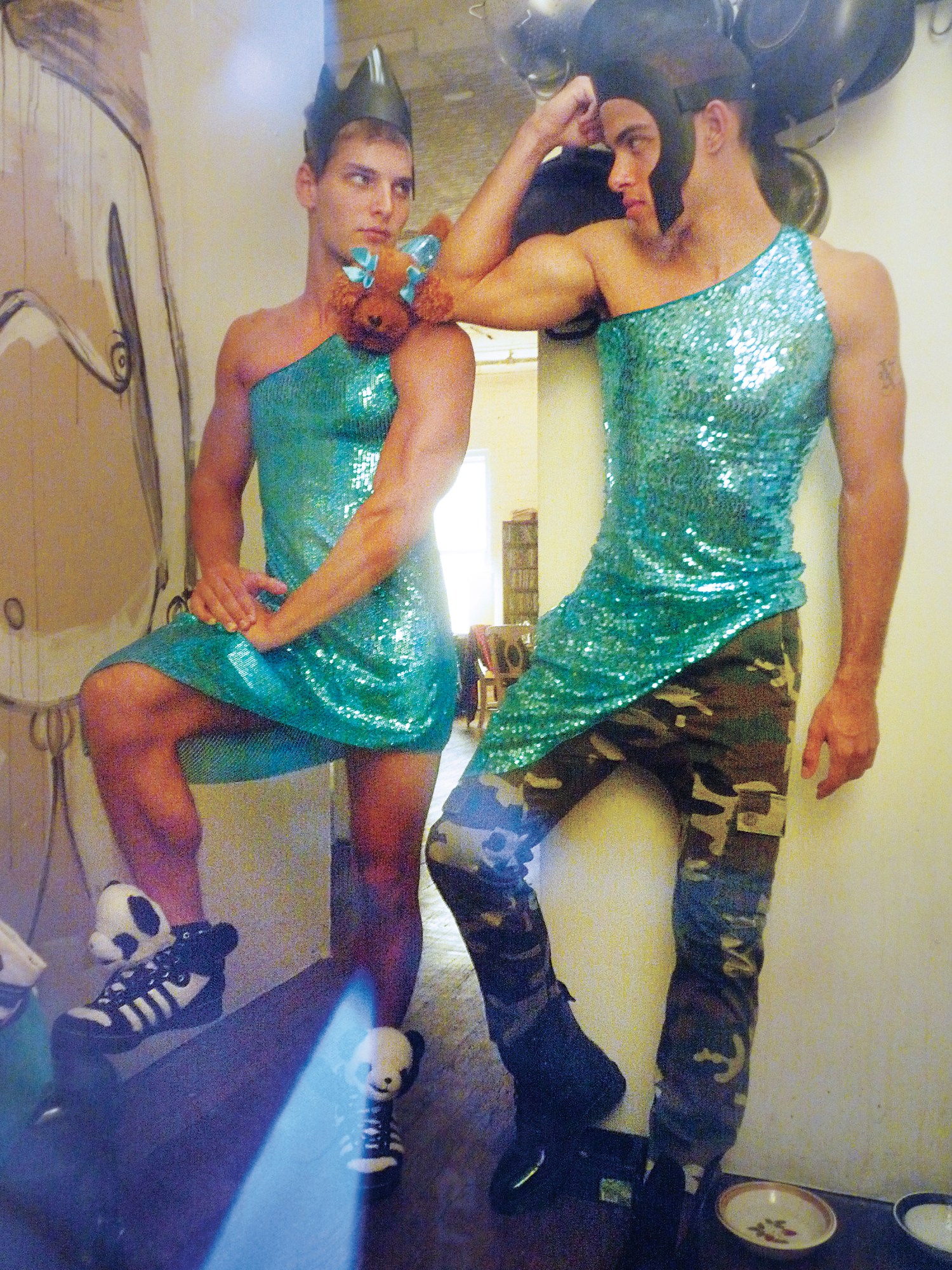

In his new home Slava’s work flourished. His first book, Lost Boys, was published in 2006 featuring provocative pics of Crimean rastas, Russian wrestlers, military cadets, German skinheads, and football hooligans. The book deconstructed masculine stereotypes, was homoerotic as hell, and made Mogutin a cult star.

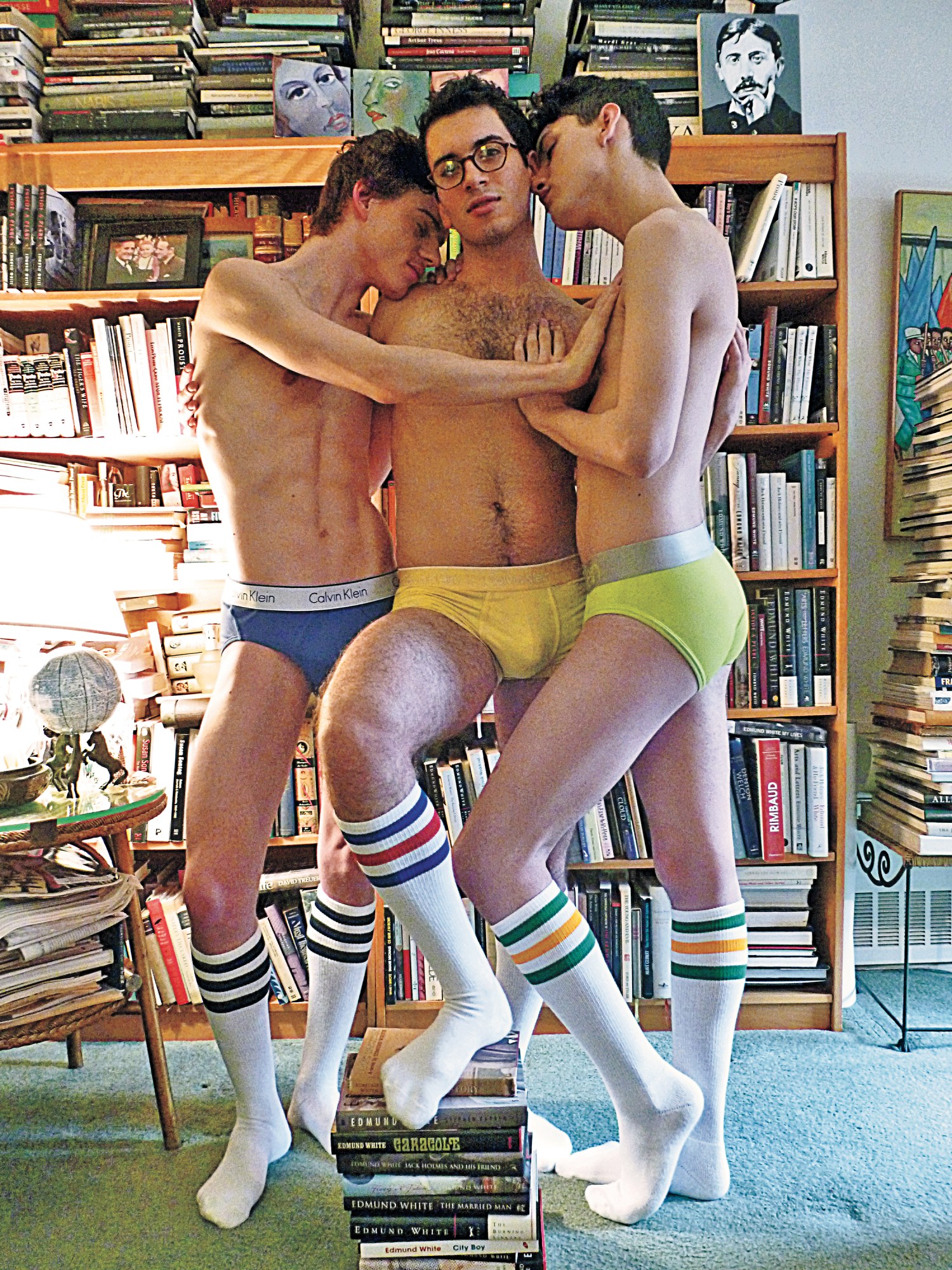

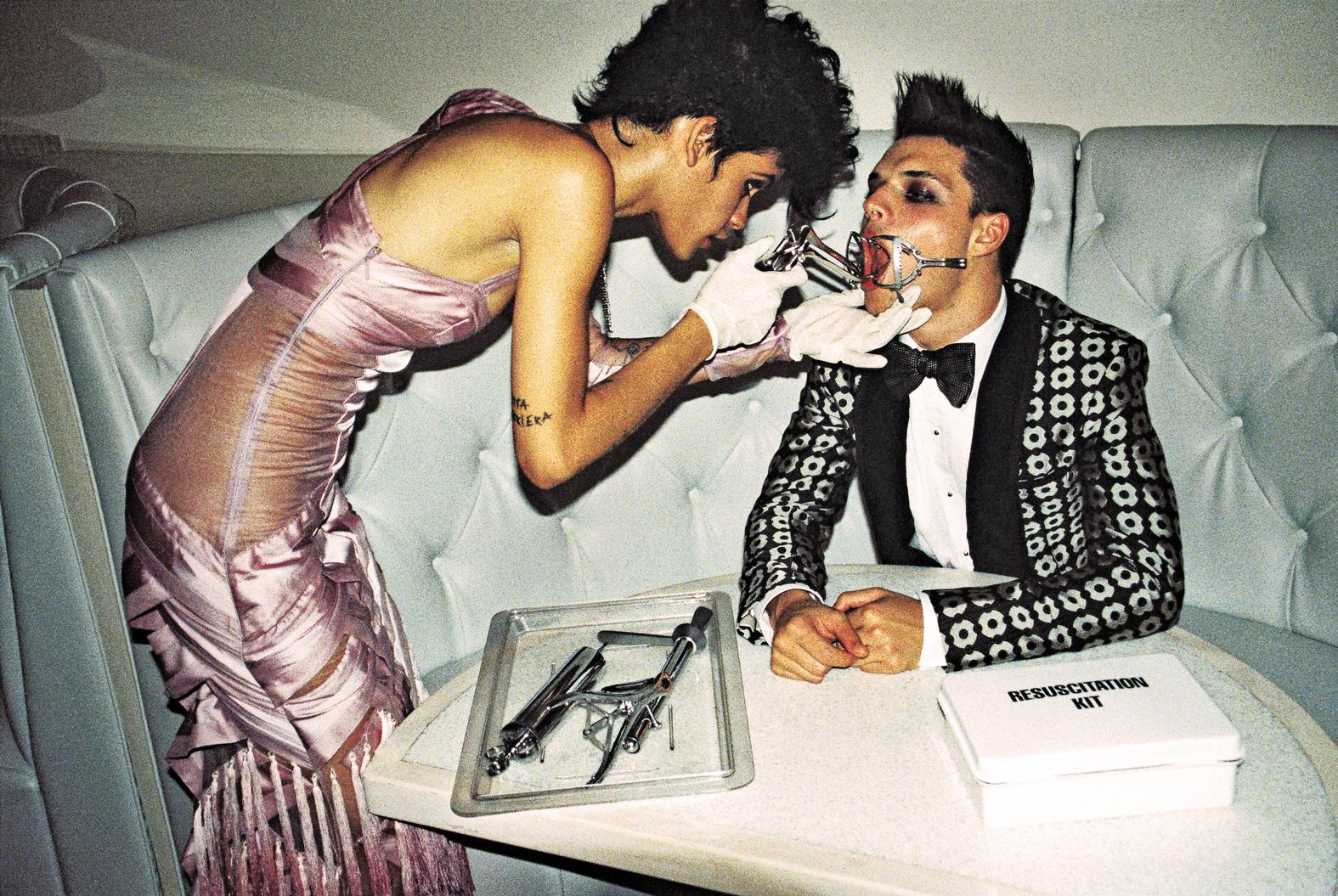

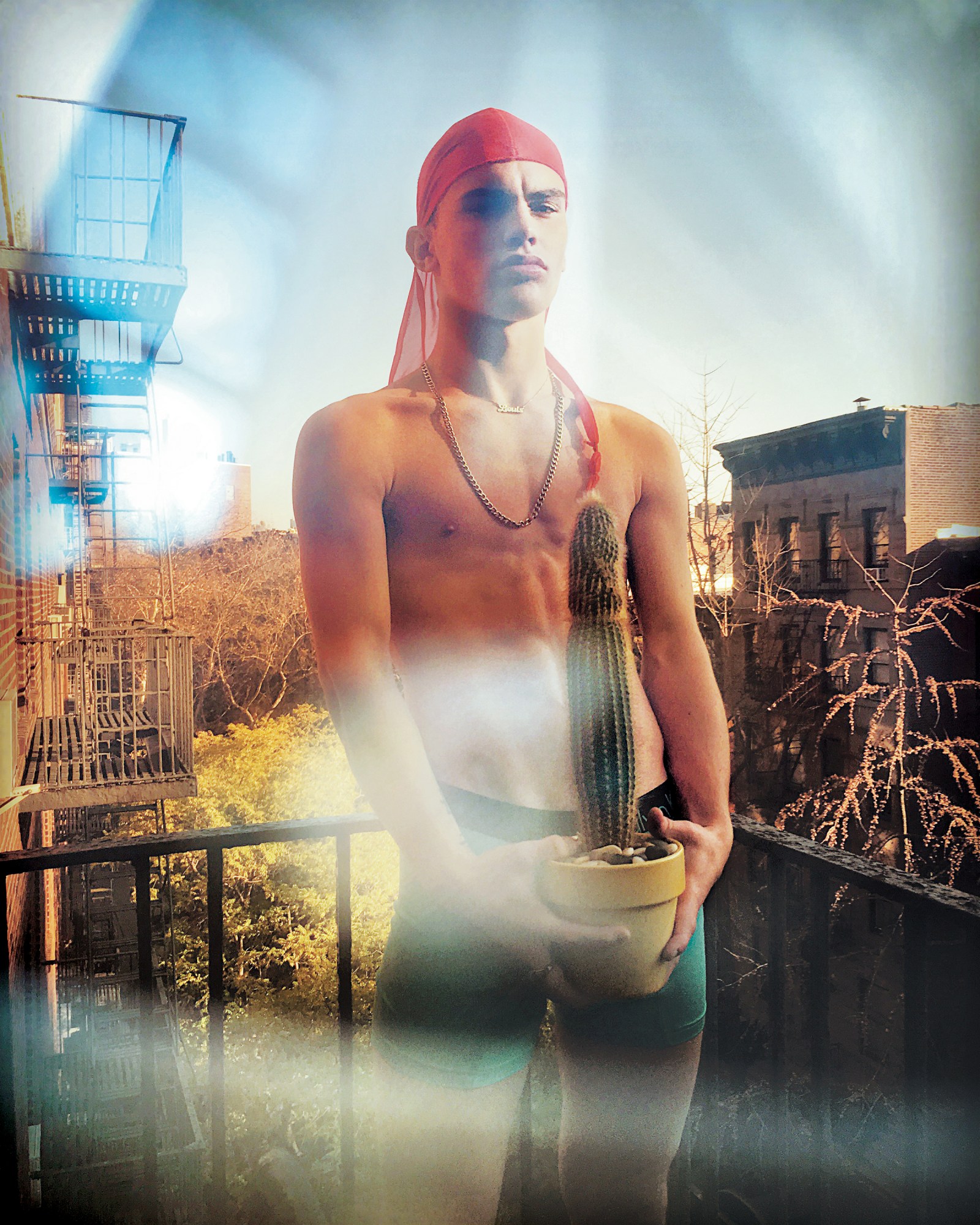

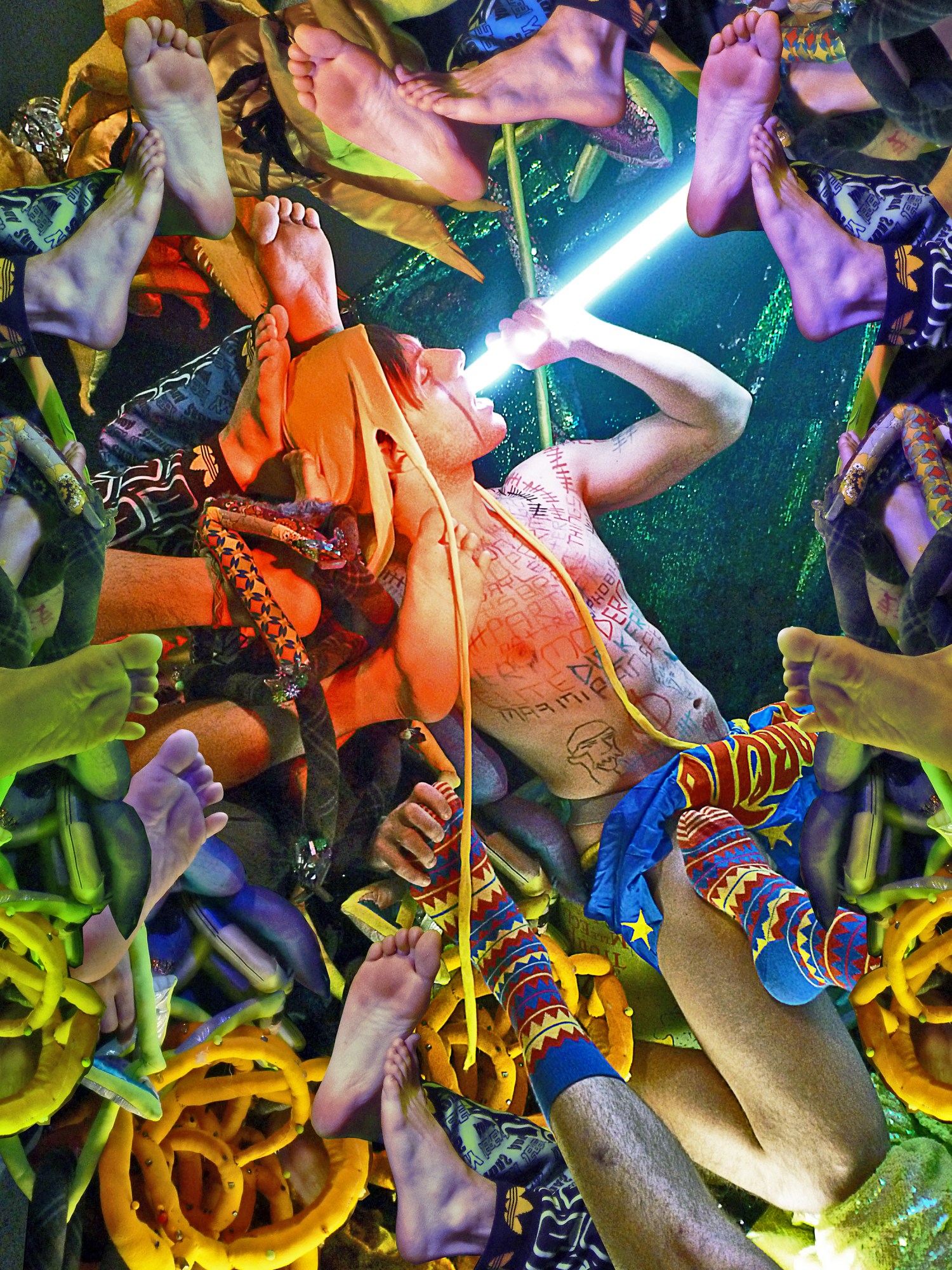

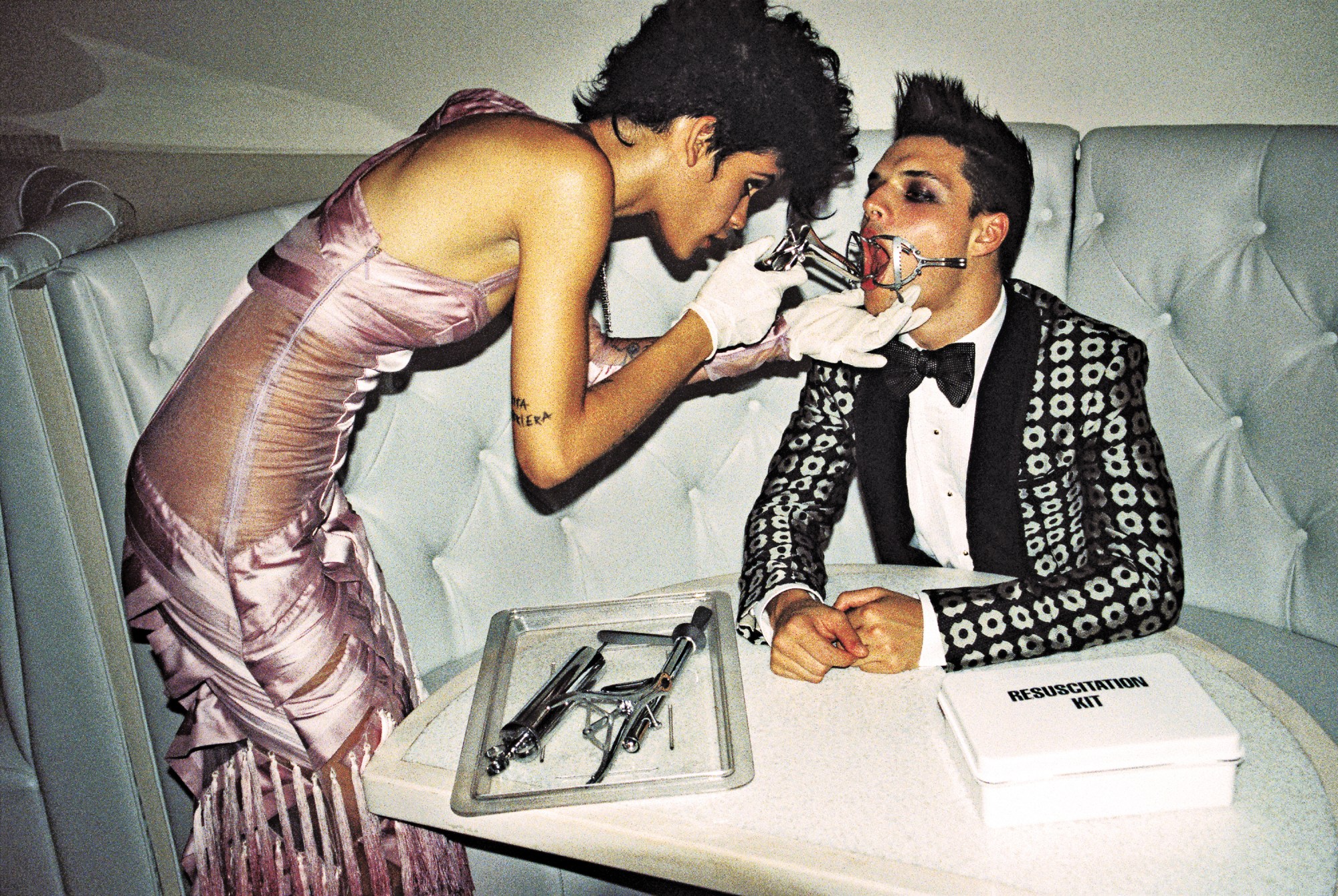

His new book, Bros & Brosephines, brings together Slava’s studio and fashion photography, commissioned portraits and unseen early work that predates his relocation to the US. The book further challenges conventional notions of beauty and masculinity and — perhaps for the first time in Slava’s work — overtly explores gender fluidity and the feminine, and continues to explore fetishes, so you’ll see plenty of jockstraps and blowbacks. It does all this with authenticity, because Mogutin not only documents but lives a radically open and engaged queer existence, challenging norms, promoting acceptance and sexual liberation.

Your new book features work spanning the last 15 years, what’s changed in your work and life in that time?

Everything has changed and nothing will ever be the same. 15 years ago I was still writing in Russian and taking the snapshot pictures that later became Lost Boys. Since then, I’ve travelled the world with my work, collaborated with some of my favourite artists, and experimented with different mediums, formats and genres, from porn to fashion and art, then back to porn again. There are 17 chapters in the book comprised of projects shot in various locations from Moscow to New York, Amsterdam, Berlin, Paris, California and Miami. There’s a common narrative that brings all these different bodies together. It’s about queer utopia, questioning traditional patriarchy, masculinity and gender roles. It’s also a very personal book that tells the story of my great love conquests and failures.

What influence has New York had on your work?

New York is a place where I found my refuge and family and I’ve been happy to call it my home for over 20 years. I met some of my teenage heroes here and it served as a perfect backdrop for countless pictures and my book NYC Go-Go. The cover image and final chapter of Bros & Brosephines were shot on my beautiful fire escape in Greenwich Village. And several others were shot at my old studio on 14th Street, which used to be Wolfgang Tillmans’s studio, so it had a very unique energy.

Queer art has it’s own rich history — but what’s your take on queer art today? Is it doing a good job of challenging issues?

Being queer by definition means being different, being a rebel, an outsider, a fighter. It’s about challenging the status quo, questioning authority, standing up to the elite — the rich and the powerful. Queer art now is just as threatening to the mainstream as it was at the times of Robert Mapplethorpe, David Wojnarowicz and Derek Jarman. Today our fundamental constitutional rights are under attack and we all must rebel, resist and fight back. Queer art is my weapon of choice.

You’ve been vocal and on the receiving end of censorship on social media platforms, even writing an open letter to Mark Zuckerberg about it. Why is nudity still such a taboo?

There’s no reasonable way to justify this rampant homophobic censorship. Social media has become a global KGB: they censor, ban, delete and erase whatever and whoever they choose. This censorship monster seems to be turning a blind eye on countless openly pornographic (and mostly heterosexual) profiles while constantly attacking and policing queer community. I’ve been censored in Russia and America, it must mean I’m doing something right. Regardless of their ridiculous and shameful policies, I believe in freedom of speech, press and artistic expression and my right to exercise these freedoms. If you don’t like what I say, write and post, don’t follow me, but don’t try to silence or censor me just because you disagree with me. It’s as simple as that.

What have you learned about human nature and people’s relationship with their fetishes?

Fetishes are subconscious reflections of human psyche and sexuality, it’s what makes us different from animals. Everyone has a certain fetish even if they never admit or recognise it — unless they have zero fantasy and imagination. I feel sorry for them!

What’s yours?

If you want to find out, just look at my books. My work is an encyclopedia of fetishes, too many to list here.

What are the similarities or differences between how you approach poetry and photography?

For me it’s all part of the same creative process and narrative. Poetry is photography and photography is poetry. I can create a picture out of a poem or a poem out of a picture. As long as I have a pen or camera in my hand, I can always come up with a story.

What’s your take on the rise of the Russian aesthetic in the fashion world? Is it nostalgic for you?

I haven’t been back to Russia in a very long time and I cannot say I feel particularly nostalgic about totalitarian aesthetics. There’s definitely something in common between cheap Trumpian kitsch and Putin’s neo-imperial propaganda, they both cater to the same type of nouveau riche gangster capitalists. I feel like in Lost Boys I’ve captured post-Communist Russia in a very personal, honest and poetic way, and that was nearly 20 years ago. What you see now in fashion is a mere cultural replication.

Who are some of the subjects you shot for Bros & Brosephines? What’s their story?

There are boys, girls and some of those in between. I mostly work with friends and volunteers and let them tell their own stories. I was fortunate to collaborate with a great team of fellow artists and personalities and each of them brought their unique voice and vision to this project.

You typically use pretty attractive bodies in your work, have you considered exploring other less conventional body shapes in your work?

I’ve captured plenty of bodies, all sort of bodies. I’m working on a couple of new book projects that have nothing to do with gender or sexuality. One is of artist portraits — I’ve been really enjoying working with mature people like Marina Abramović, Chuck Close, Gilbert & George, Edmund White… And now I’m shooting a series of portraits in the town of Rugby, with a wide range of bodies and ages from 16-year-olds to guys in their 50s. They’re real rugby players, not your regular model types. The whole project is about diversity of personalities, faces and shapes. For me it’s all about inner beauty and spirit.

What camera do you shoot on? Do you remember your first camera?

I use different cameras, like my trusted Lumix, Leica, Olympus, Yashica, and Holga. I switch between digital and analogue, and I love shooting with old Polaroid cameras. My first camera was an old Soviet FED camera, which I borrowed from my dad as a teenager. Back in the day, he was an aspiring photographer. I had a primitive photo darkroom set up in our bathroom, causing inconvenience for the entire family. Unfortunately, my family was never supportive of my work, which my Dad once described as “anal filth.” Thanks Dad!

Artwork from Bros & Brosephines by Slava Mogutin published by powerHouse Books