If you follow the basics – a clean record and good academics – you can bank on steering clear of the criminal justice system. Right? For most of us, perhaps, but for others, the odds are less kind. Especially if you’re young, Black and male. That’s because, in the UK, you can be tagged “guilty by association.”

Just over a year ago, a case in Greater Manchester presented a microcosm of the problematic legal principles that yield that tag. Joint enterprise or conspiracy, for instance, can put someone in the frame for a serious criminal offence, even if they did not inflict any harm.

These prosecutorial tools are key to building “gang” narratives, which have been found to be racist, sometimes using social media use, drill music videos and private chat content, evaluated by legal professionals out of touch with the constituents they’re seeking to convict. Moreover, how such information is interpreted sets a worrying precedent and a path towards increasing “pre-crime” in the UK.

The Manchester case in question, dubbed the “Manchester 10” by advocacy and youth organisation Kids of Colour – representatives from which were heavily involved in supporting the boys involved – saw 10 young Black men charged with conspiracy to murder and conspiracy to grievous bodily harm. The prosecution claimed the group was a gang, linking them to a murder they alleged was retaliation for their friend’s death.

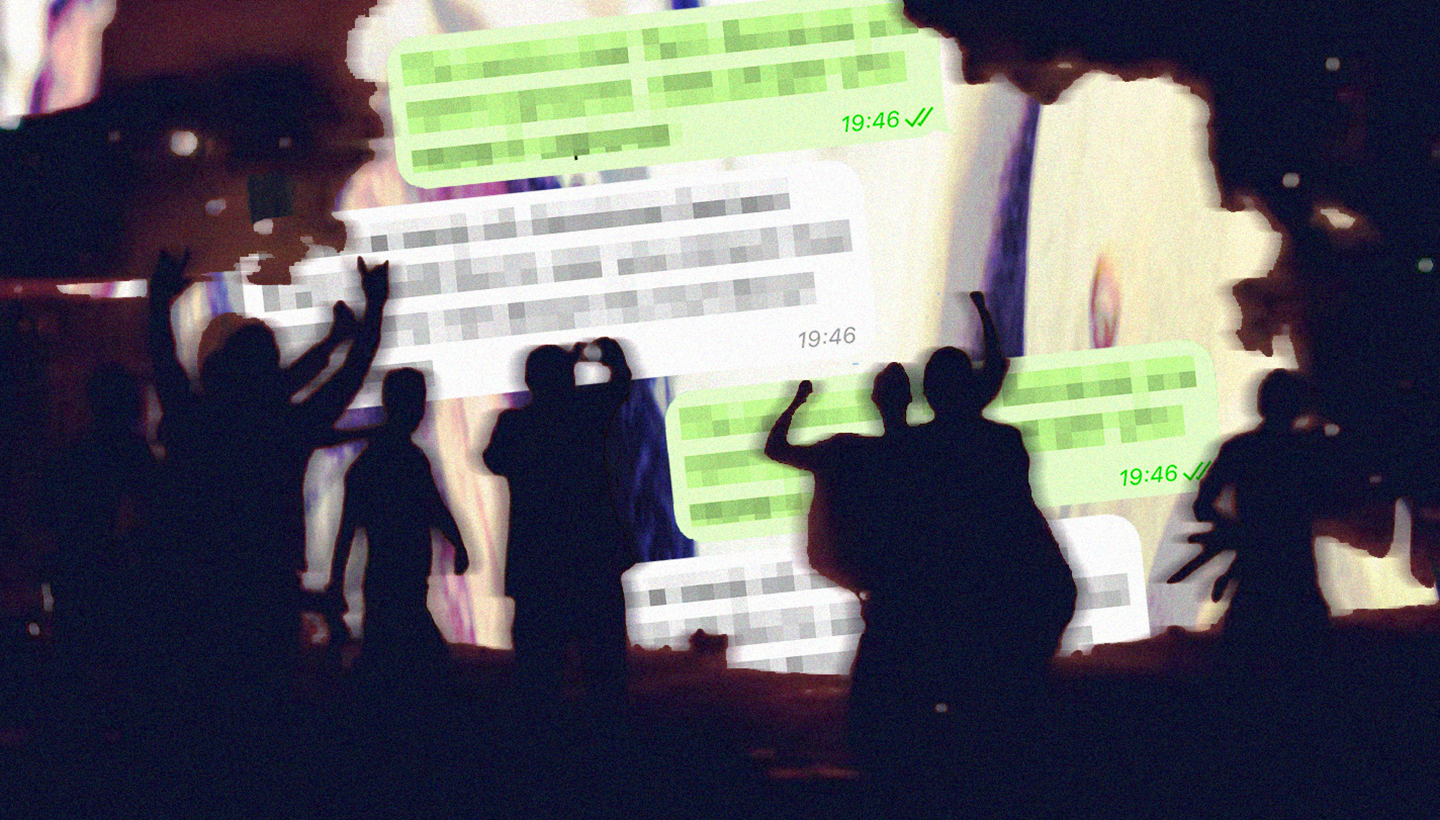

A Telegram chat where the group, connected mainly by their grief, came together to express their pain became critical evidence against them. However, no one mentioned in the group came to any harm. Still, the prosecution used the chat, drill music references and social media posts to create the gang narrative and hold them “guilty by association.” Although most of them had not done any actual harm, they were sentenced as if they had.

Where I work at Open Rights Group, looking at digital harms impacting over-policed communities, it is how social media and content are used as evidence that raises concerns. In the seemingly safe space of friend networks, young people flex and exchange words, post videos and may even write lyrics portraying the kind of life and environment around them – one that may be violent. However, that content can be mined and construed to demonstrate ‘gang’ culture or drawn on to illustrate intent.

Guidance written by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) states that “gangs are increasingly using drill music and social media to promote gang culture, glamorise the gang lifestyle and the use of weapons.” In a case similar to the Manchester 10, involving young people from Moss Side, Manchester, a music video – a project organised by a local youth group – formed part of the evidence to argue the defendants were a gang.

Notably, the CPS also stresses that prosecutors should consider whether a substantive offence is disclosed and many say that such content is often the stuff of fantasies, just as violence in video games or films are accepted as fiction. ORG has also heard that the ‘gang narrative’ using such content is the last ditch attempt when there is no other compelling evidence.

Experts have repeatedly hit out at the demonisation of Black musical expression. Joint enterprise, key to building the narrative, further compounds the disproportionate impact on Black people who are prosecuted under the common law principle more than white people.

And while the resulting criminalisation is bad enough, more sinister is the use of the content within the increasing trend of predictive policing. The Metropolitan Police Services’ Gangs Violence Matrix, a watchlist that holds anyone at risk of being involved in or from gang violence, was also based on associations, musical tastes and social media activity. ‘Nominals’ on the list have been scored against the likelihood of committing violence, while most people recorded on the matrix are Black.

The database has been deemed unlawful, yet it doesn’t serve as the Met’s only tool to ‘pre-criminalise’ content. Last year’s revelations around Project Alpha – which targets serious gang violence inspired by social media, including drill videos – heightened concerns as it exposed the project risked profiling children’s data on a mass scale, focusing on young men aged 15-21. Police forces are also operating gangs databases up and down the country, including in Manchester.

The extent to which data sharing and matching occurs (which has caused harm to other vulnerable groups) and how much information is fed through automated decision-making tools and algorithms is not fully known. Yet, what we do know is that risk profiling can impact people’s lives. For instance, those who have found themselves on the Gang’s Violence Matrix, often in error, can be affected through their benefits, housing and education.

The weaponisation of content, coupled with extended criminal liability charges like joint enterprise, conspiracy, possession and preparation offences, form a worrying trajectory for criminalisation. However, it also serves as a worrying route to and picture of an enlarging pre-criminal space in the UK that is overwhelmingly racialised.

Denying young people the chance to enrich their communities through such racist policies is not just a harm to them, but to society as a whole. And behind the Manchester 10 case was a large community willing to support the young people.

That is why we wrote to Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham in an open letter signed by 15 civil society and youth organisations, asking him to support calls for the police to review how they use digital evidence. Burnham has already pledged to demand changes to how joint enterprise is used and perpetuates racial bias.

If he, and the policing institution he is responsible for, care about eliminating racism, they must yield calls to address the harm caused by the outcome of Manchester 10 and the increasing criminalisation of young people’s content.