A while ago, my group chat was discussing how fit a celebrity, probably Cole Sprouse, was when, suddenly, the conversation took an odd turn. “Ugh, I would let him run me over in his car”, my friend sent. “I would lit let him ruin my fucking life. Like, dead.” It seems overdramatic and morbid, sure. But, really, my friend was just adopting the hallowed language of stans.

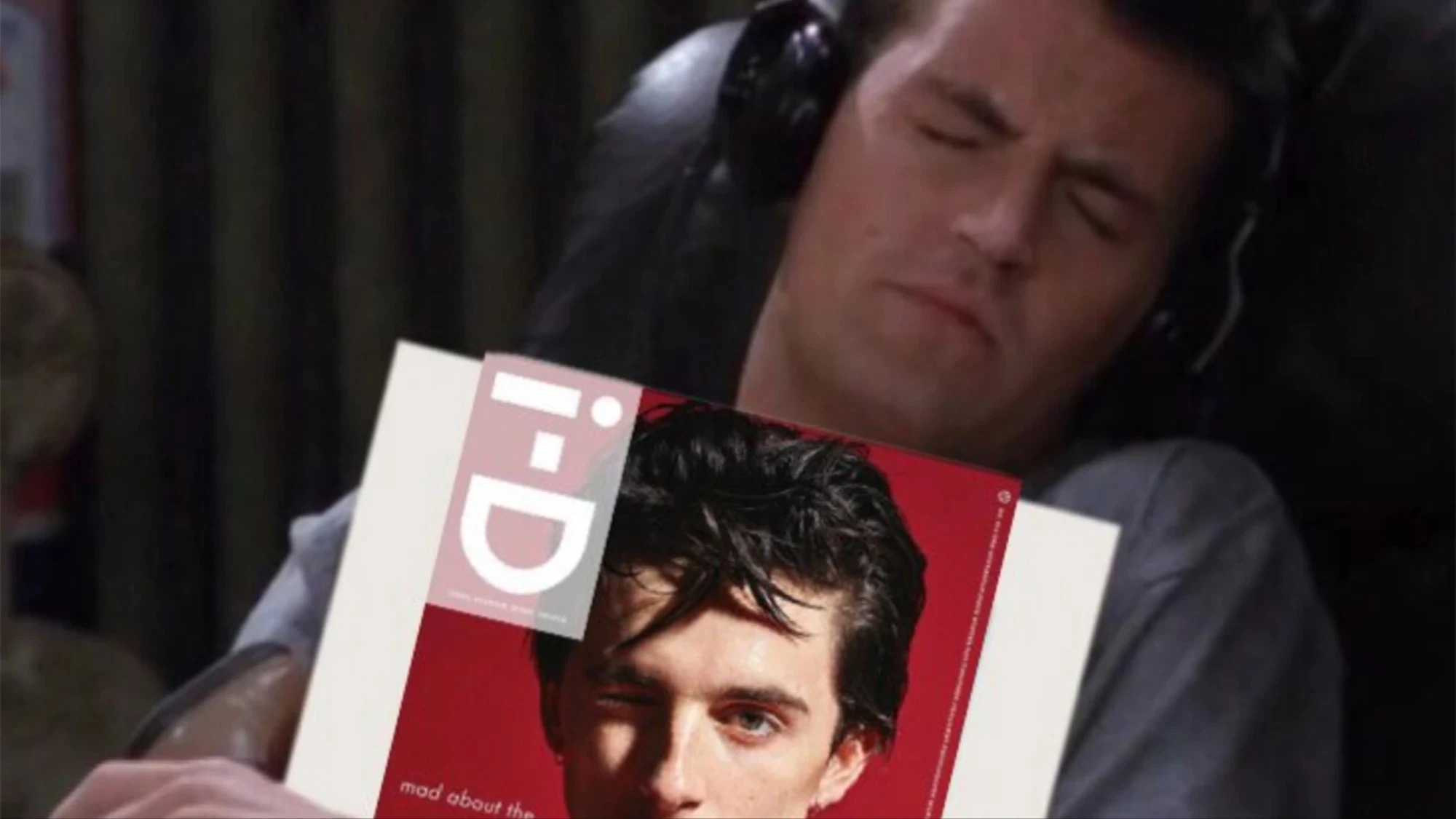

i-D’s own DMs took a turn for the stranger when the stans invaded a few weeks ago, after we dropped our new Timothée Chalamet issue, in which the heartthrob was interviewed by fellow heartthrob Harry Styles. Suddenly our social media was flooded by teenagers yelling (in caps lock, obviously) about skinny legends, snatched wigs and death. It’s not just Harry or Timothée either. On Tuesday, for instance, Twitter user @mindofglitter — a reference to Mariah Carey’s Glitter — wrote “dear Zayn fucking Malik, you could punch me, throw me against a wall, run me over with your car, kill me and I’d still scream ‘THANKS DADDY’ from my grave. Truly yours, me. A skinny legend.” This is fan mail, but taken to the nth degree.

Now, obviously stanning — the term taken from Eminem‘s 2000 single about an obsessive fan — is not new. It dates all the way back to the dark ages of Beatlemania. The difference now is that stanning is playing out linguistically on social media rather than just screaming at celebrities in car parks or crying as you camp outside their hotel rooms. It’s a change linked primarily to the greater access to the rich and famous that we now have online, explains linguist Rob Drummond. “The main reason that fans will speak like this on Twitter is simply to get the attention of the celebrity by outdoing your ‘stan peers’ with more and more extreme language,” he explains. “Part of the reason it’s become such a big thing is that we have such easy access to the celebrities we admire and obsess over. People know that there’s a chance the celebrity will actually read their tweet, so they do what they can to make their message stand out.”

Basically what he means by that is: yes, there might be five thousand 12-year-olds commenting “UGH FUCKING KILL ME” under everything Harry Styles posts on Instagram, but no, they do not actually want to die. When it comes to extreme emotion vs posturing, Rob says that the former is the exception rather than the rule. “With any group of obsessive fans there will be a few who are genuinely taking it too seriously,” he tells i-D. “But the majority are just caught up in the trend. The difference between pre-social media days is just the speed and ease with which these views and language can adapt and be shared. If you subscribe to the view that people are using extreme stan language in order to get noticed, then it makes sense that people will rapidly try to outdo each other. It’s a great example of how interesting and inventive language can be.”

Beck Martin is a 24-year-old student from Illinois. She’s also one of the Harry Styles and Timothée Chalamet superfans who lost their minds when we dropped our cover interview with the superstars a few weeks ago. Beck has even dedicated her entire Twitter presence to her love of both celebs (her handle was briefly @himothee, although she has now changed it to @erskinerecords, a reference to Harry Styles’ independent label). “Harry and Timothee are my absolute favourite people in the whole world”, she says. “When they do anything, I’m ecstatic.”

Beck explains that both fanbases are extremely active and thrive in supporting both Harry and Timothée, which in turn can lead to some pretty frenetic stans. “I need someone to collect my uterus immediately”, wrote one, replying to the news that Harry had interviewed ‘Timmy’ for i-D’s Superstar Issue. The other replies were equally, um, extreme. “The second either of them do anything, we’re excited to scream about it,” Beck says. “You find yourself feeding off how excited the rest of the timeline is. It’s like being in a room full of really ecstatic people. I find myself doing a lot of key smashes and screaming.

“A lot of stan language comes with reaction pictures and memes to express how you feel, but sometimes you get so excited that you can’t even think straight enough to come up with something witty to say. Stan Twitter language comes in phases — when something new happens, there’s usually a shock phase when nobody says anything of value, just lots of key smashes and incoherent yelling. Then, whenever the news starts to settle in, that’s when you get the funny reactions and memes.”

When she first found out about the Harry/Timothée interview, Beck’s response was typical of the incoherent, excited stan language she describes. She tells i-D she ended up typing that she was “blacking out” over and over again. I’ll say ‘I’m crying’ or some sort of panicked tweet whenever I’m excited about anything.”

Stan language is so extreme that it’s often played for laughs, both in memes and internet communities, but the origins of the language betray how its use can often be problematic too. “Stan language seems to draw a lot from AAVE or AAE (African American Vernacular English), which is always a familiar source of slang,” says Rob, a linguistic academic based at Manchester Metropolitan University. “There’s also obviously a strong input from stereotypically gay male culture — there’s a whole subculture of gay stan culture. Both gay culture and AAVE are groups known for their innovative, inventive, performative and often extreme use of language.”

It’s easy to see where stan culture has borrowed aspects of the insider language used by both the black and LGBTQI communities — the popular “wig snatched” expression springs to mind, or the era where every teenage girl on Instagram suddenly started yelling “yass queen” after seeing it in that one episode of Broad City. There’s even the mainstream adoption of slang like “serving face”, and “realness”, once the language of the black and Latinx ballroom scene, popularised through Paris Is Burning and now repackaged for the masses by RuPaul’s Drag Race. And the wider implications of this linguistic appropriation are arguably pretty problematic.

When Katy Perry used “wig snatched” as an awkward gag during her disastrous stint as host of the MTV Awards in 2017, it was cited as another example of the singer’s unapologetic cultural appropriation. As terminology like “bitch, me too, the fuck” and “on fleek” entered the lexicon of internet speak through viral Vines, later reposted to YouTube and Twitter, the language of black teenagers was adopted by groups made up largely of white, heterosexual teens, sparking debates over whether this linguistic crossover was an example of respectful adoption through admiration, or a more insidious form of cultural and linguistic appropriation.

Through this appropriation stan language remains insider language, but now repackaged and reused by a wider audience. Rather than being the chosen slang of AAE or the queer community, stan language has increasingly become another example of the generational gap in speech patterns, differentiating how millennials and Gen Z teens navigate the internet (and real life). As stan language becomes “weirder” it also becomes a more obvious example of how young people are adapting language in their own way.

Whatever its origins, the adoption of stan language clearly fosters an inclusive attitude between users. Stan communities have proved themselves to be a lifeline; a place in which young people can join together, ostensibly over a celebrity, then use the communities formed as a place for support. Much of the Harry Styles fandom, for instance, is rooted in LGBT rights, so much so that Harry wears Pride flags onstage at his gigs and even helps his dedicated stans to come out to their parents. Sure, the language of the communities may appear extreme, but it’s ultimately a space to talk to other people about love.

I asked Beck about the endless “I’m dead” messages in i-D’s inbox, and she gave a characteristically positive, lovely stan explanation. “That’s pure love! It’s an utmost compliment. Like… wouldn’t it be cool to positively affect another person so much that it just makes said person feel like they could die by how excited they are? Just by the fact that you exist? You know?”

Yeah, we do know. We stan.