Think of The Shining and what comes to mind are the cornflower blue dresses of the demonic twins lurking in the empty corridors of the Overlook Hotel; think of A Clockwork Orange, and you picture Malcolm McDowell and his droogs stalking a brutalist London streetscape in white boiler suits, jockstraps and bowler hats; think of Barry Lyndon and it’s the opulent taffeta gowns and feathered caps, or the meticulously recreated military uniforms.

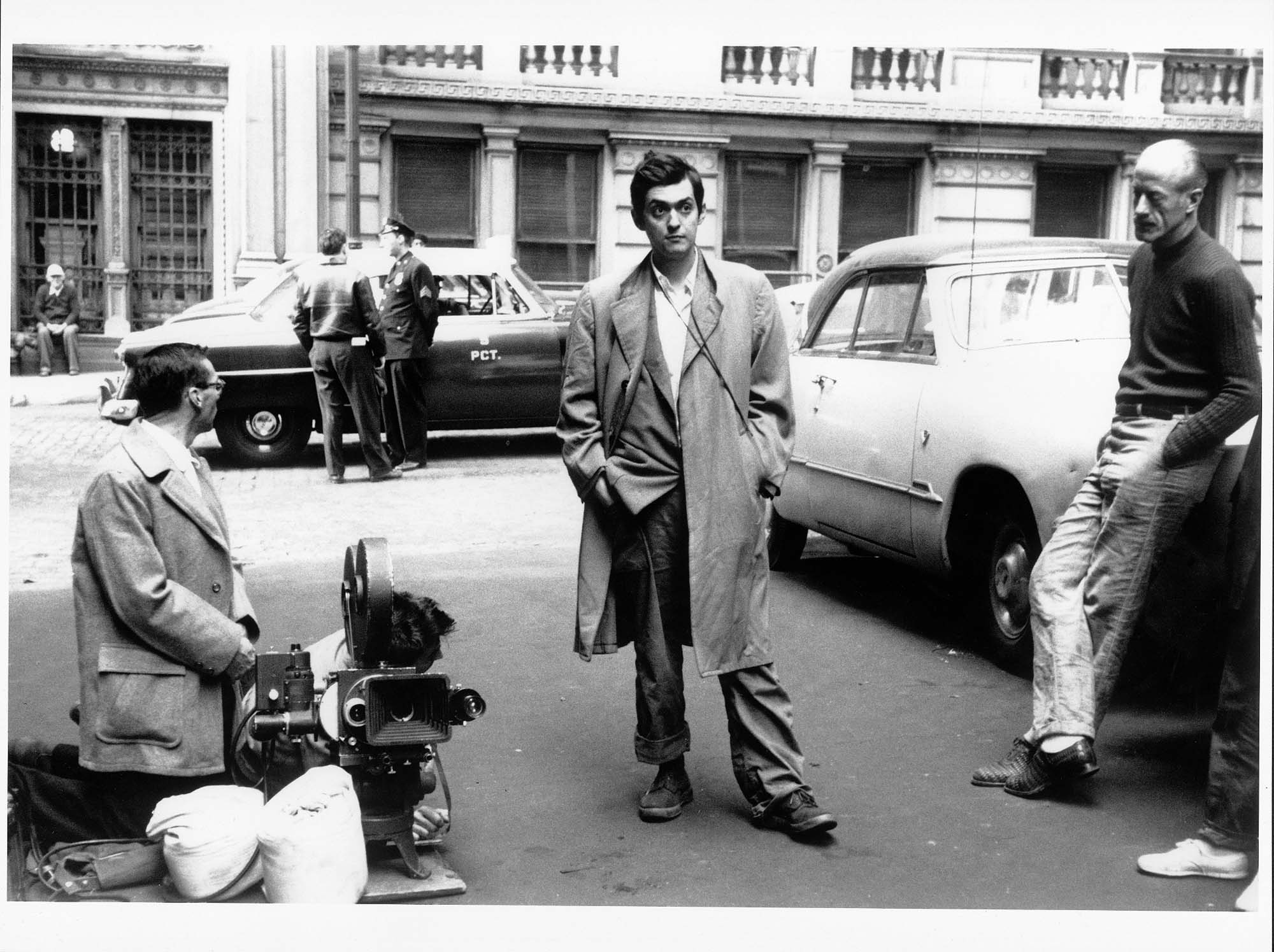

Stanley Kubrick is celebrated for his ability to endlessly reinvent himself, turning his hand to every genre from dystopian horror to war epic to political satire and delivering a masterpiece each time — but the razor-sharp eye for costuming that enabled him to paint these vivid windows into other worlds has often been overlooked. A new exhibition at the Design Museum is putting his collaborations with art directors and costume designers in the spotlight for the first time, and it’s the latter that proves the greatest revelation.

“Perhaps it speaks also of the masculine world of film geekery that Kubrick’s relationship with fashion has been largely overlooked until now.”

“As a museum, our interest is in exploring the process, the development of how things are made,” explains the exhibition’s assistant curator Adrienne Groen. “We really have a chance to focus on the people Kubrick collaborated with, rather than just the film as a final product.” Kubrick’s collaborations with the figures who brought to life his vision for costumes are explored throughout the exhibition with unprecedented detail: in particular, his rich working relationship with costume designer Milena Canonero, who served as costume designer on Barry Lyndon, A Clockwork Orange and The Shining, working with the same unmatched versatility as the filmmaker himself.

“A lot of people say that Kubrick was involved every step of the way, and he was, but he was also working with the best people so he was able to give them plenty of freedom,” says Groen. “There would be huge amounts of research, but then someone like Milena was able to give it her own twist.”

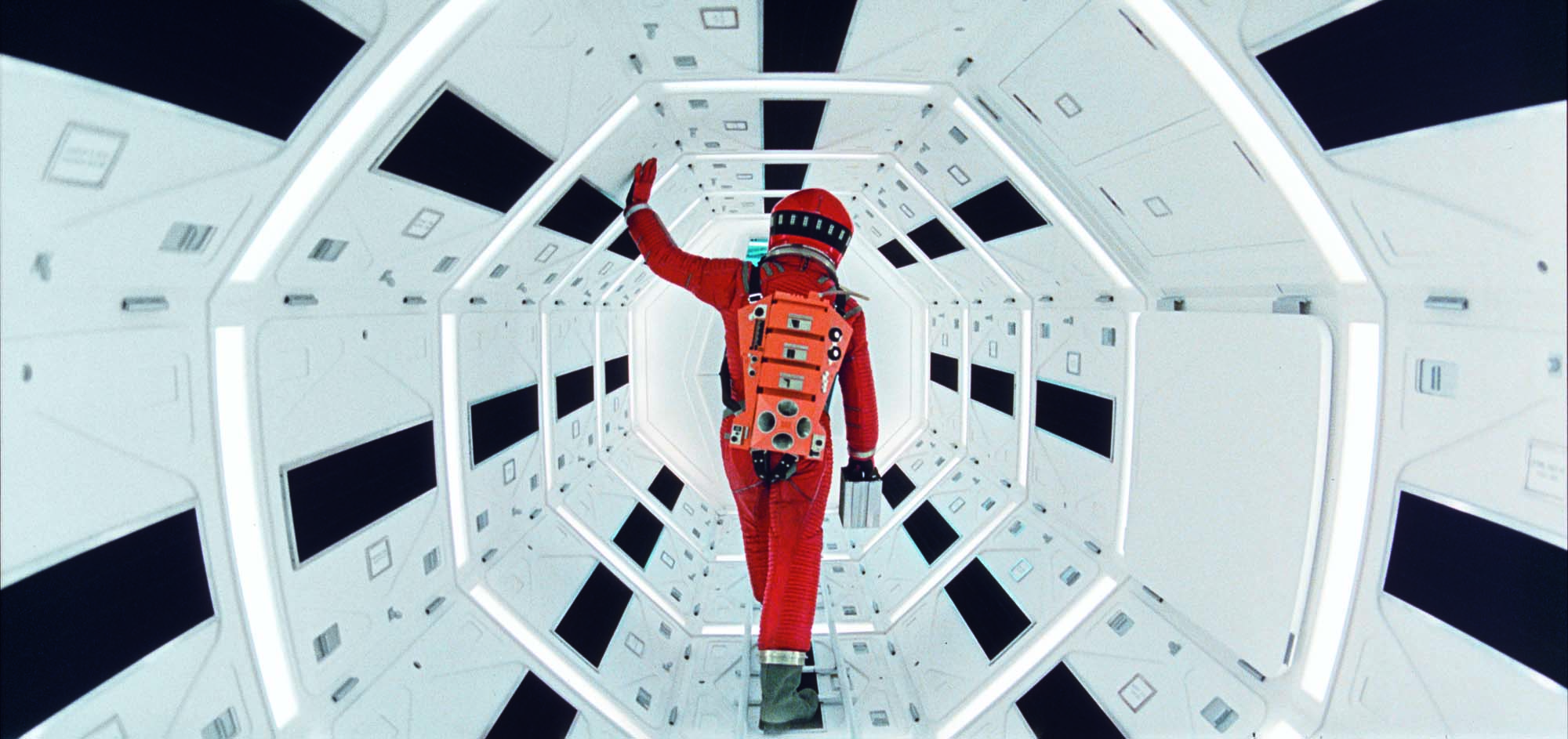

Also explored is Kubrick’s unlikely relationship with the legendary Savile Row tailor Hardy Amies, who worked as a costume designer on 2001: A Space Odyssey. The mod-inspired outfits worn by the film’s Pan Am spaceship crew and passengers might carry echoes of the 60s space-age visions of André Courreges and Pierre Cardin, but Amies was hired specifically for his rigorous and highly traditional training: to create something that would still feel futuristic many decades down the line. “With 2001, Kubrick was looking for something that felt beyond time,” Groen adds.

Perhaps it speaks also of the masculine world of film geekery that Kubrick’s relationship with fashion has been largely overlooked until now. After all, Kubrick’s vision was precise to the point of obsessive: a fact emphasised by the exhibition’s imaginative design, produced by Pentagram partner Marina Willer, that sees the first room consist of screens that offer a 360-degree immersion into his famous use of one-point perspective.

This fixation with symmetry extended to every aspect of his productions, all micro-managed to within an inch of their lives: whether that was the infamous 127 takes required to capture Shelley Duvall’s horrified screams while swinging a baseball bat at Jack Nicholson in The Shining, or the painstaking research he undertook while preparing for his never-completed epic on the life of Napoleon, which the exhibition sheds light on with its displays of the director’s extensive research compiled by over 20 assistants. It extended to his costumes, too: while working with Hardy Amies, it’s said he delighted in learning more about and fine-tuning even the tiniest of details from the swatches of fabric that accompanied the initial sketches, to the final placement of a button.

And even if that Napoleon biopic never came to fruition, the research behind it provided the backbone for arguably his most extraordinary achievement in the world of costume: 1975’s Barry Lyndon. Based on an obscure novella by William Makepeace Thackeray, the production brought to life 18th century Europe in unparalleled detail, with Marisa Berenson — herself once a fashion model — as the mannequin-like star in feathered hats and ruffled gowns. Within the exhibition, there’s a display devoted to the exquisite dresses and frock coats that won Milena Canonero her first Oscar for costume design, as well as displays of the fastidious research that went into making sure every detail was just so.

“We were lucky, because Kubrick’s entire archive is housed in London,” says Groen. “Parts of it are in the exhibition, but it’s only the tip of the iceberg, and I think you can see that especially with a film like Barry Lyndon. The archive has hundreds of boxes filled with pages torn from art publications, art history books, everything surrounding the 18th century. It’s not just about the dress, or the cut of a coat, he really goes into the detail: how they would shave, for example. Going into those boxes you can really see what he was interested in and it’s not simply about what they were wearing, but how that related to hierarchies within society.”

“For me, it’s really about the care and the detail that he puts into everything,” Groen continues. “Every detail is so carefully considered, but also the people he chose to work with. It’s not just like a costume designer doing something for a film: they designed whole eras, in a way that felt so authentic.” As the adage goes, every stitch tells a story — and as the exhibition conclusively proves, fashion was one of Kubrick’s central tools for telling some of the most beloved (and extravagantly costumed) stories of all time.