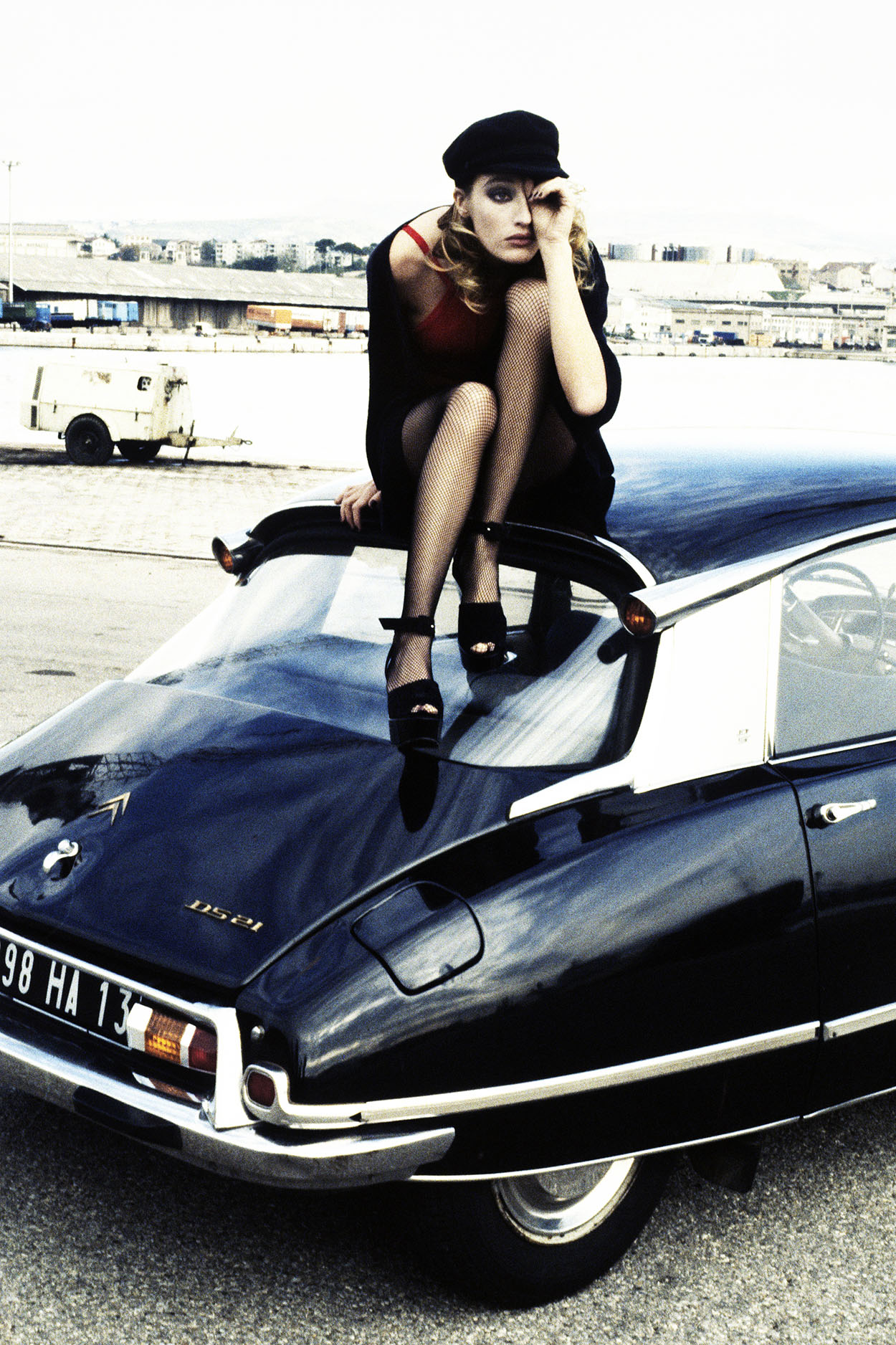

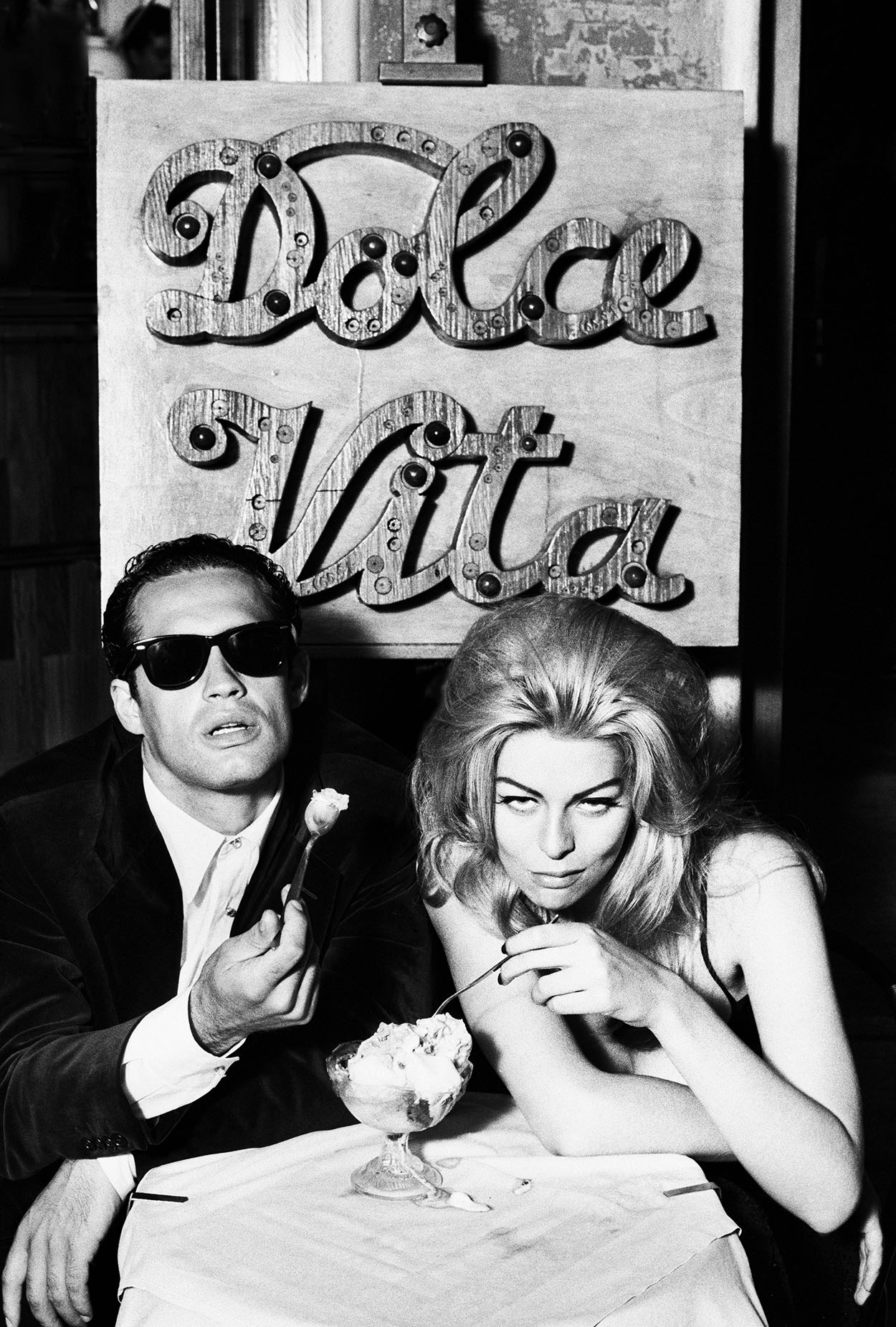

Stephanie Pfriender Stylander‘s photography archive is imbued with the spirit of the 90s. Toggling between New York, Milan, and Paris, it spans celebrity portraits — like Heath Ledger and Keith Richards — and magazine editorials — like one featuring Kate Moss (wide-eyed, fishnets) lounging with urban ennui alongside Marcus Schenkenberg (chin-length hair, sunglasses indoors). Moss, in fact, covers Pfriender Stylander’s first monograph, The Untamed Eye, which brings together 130 photographs and will be published on September 25. Her work is concurrently on view in Paris, at La Galerie de l’Instant, until November 28. While she was traveling in Bali, we spoke to her about the radical professional changes for magazine photographers and why Moss embodied La Nouvelle Vague in the 90s.

Can you elaborate on the title choice, The Untamed Eye? What connotations does it have for you?

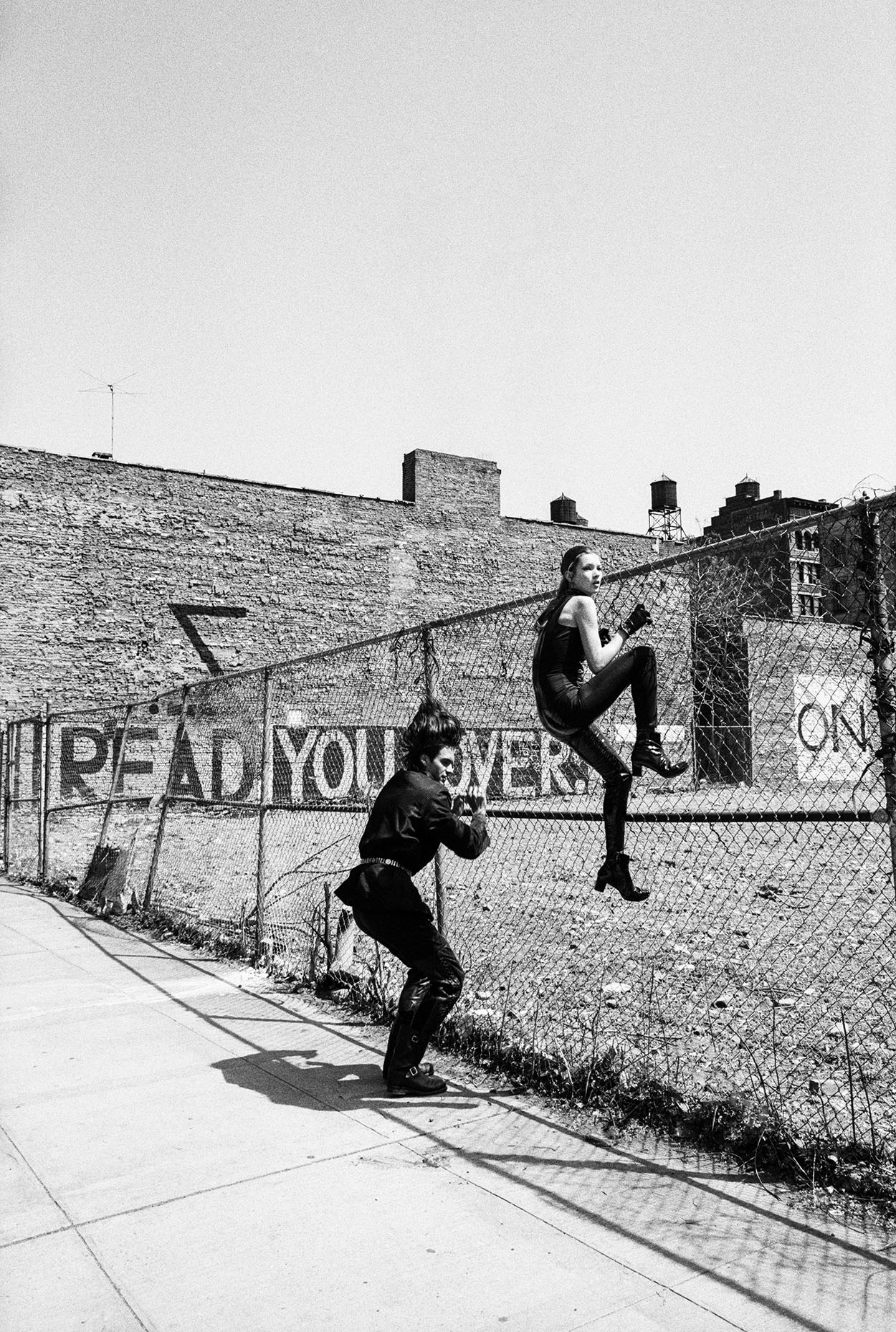

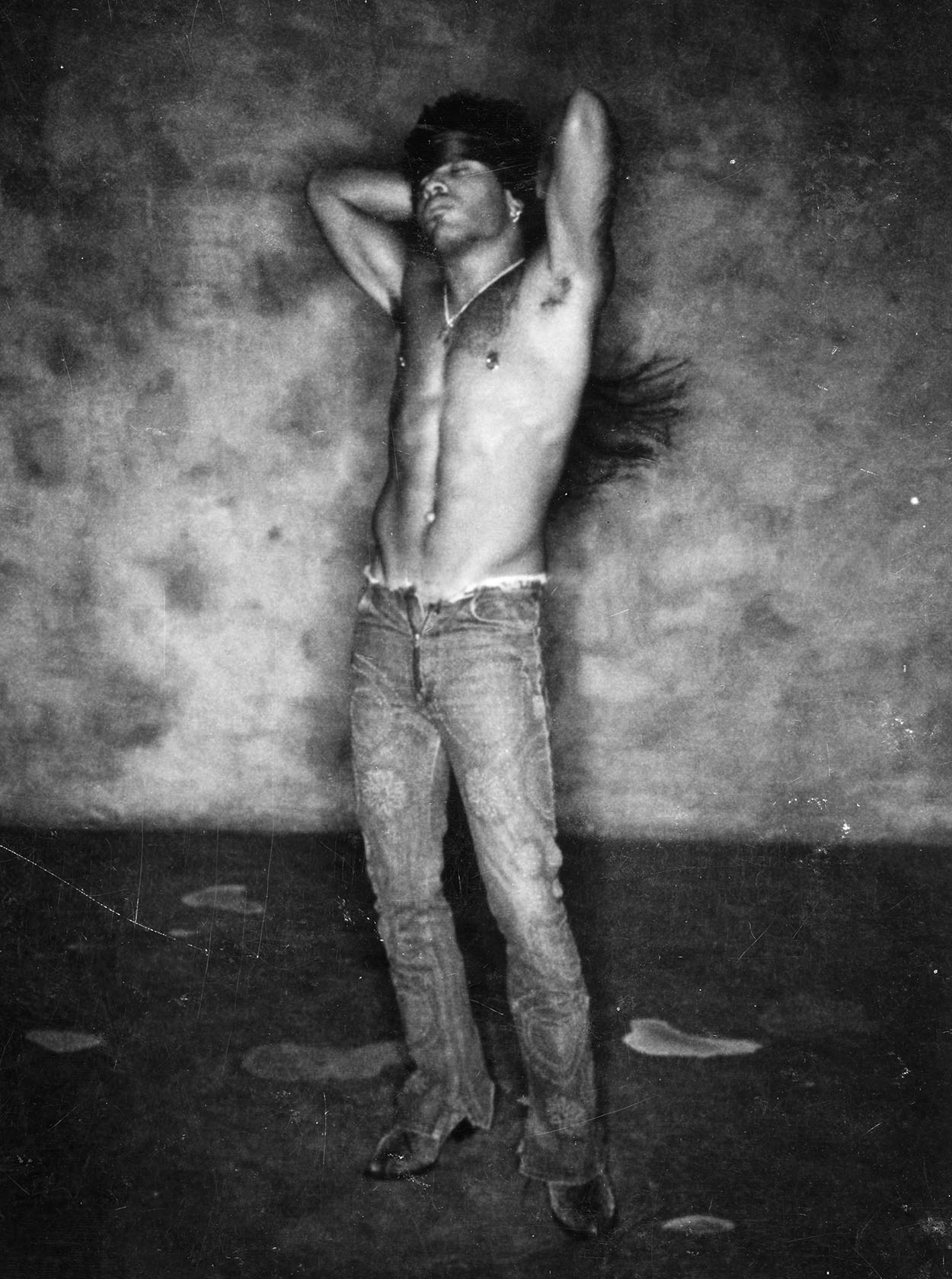

There is a wildness to being a photographer. I did what I wanted to do. I didn’t think from a fashion photographer point of view; I thought from a cinematic point of view. At times, I let go of the need to show the lines and details of the dress. My important pictures happen when I get into a stream of consciousness, a ‘dance’ with the subject: this is the part that is untamed, and for me the most interesting.

How did you decide to make Kate Moss the cover? Why do you think she remains so iconic?

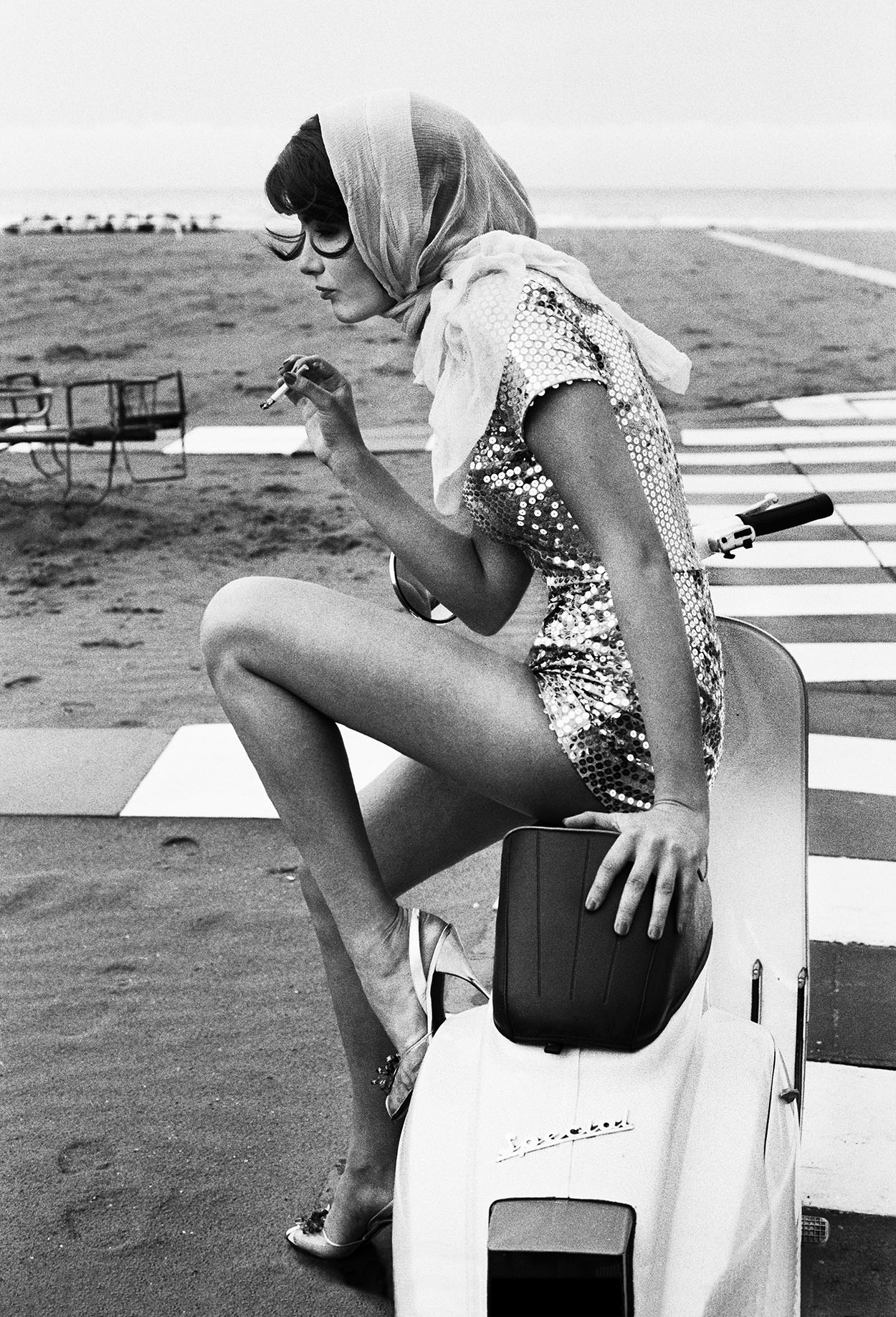

In these photographs Kate is a young unknown. While living in Paris, I watched a lot of films by Jean-Luc Godard; I was looking for an Anna Karina, one of Godard’s favorite actresses, whom I loved. I wanted this type of girl — who was a bit off, kooky, beautiful, unusual. Kate, during her early years, had an innate magic mix of power, vulnerability, curiousness, determination. When I shot these pictures, it was at the beginning of my career: we were both young, unknown, and we had a mix of power and drive. These images have become symbolic for me.

You’ve stated you’re inspired by French New Wave, Italian Neorealism, and John Cassavetes films. Who are your influences for still photography?

I love Robert Frank for his bluntness, his brutal emotion, his searing sensitive eye, his rambling. I love Richard Avedon for the power of his portraits. I love Deborah Turbeville for her consistently rough poetic style.

For a shoot, do you do a lot of research and prep, or do you tend to improvise?

Once the story is determined, I work closely with the editor, using mostly film references. The planning and communication is essential—it is the most didactic part for me. Once the shoot starts, there is always the wonderful aspect of improvisation that sometimes brings about a gem: I love this part of the process, having the room to play and get into the ‘what if.’ When I was shooting film, we could only see the Polaroid while working, and would have to wait for the film to be developed. I would have time to edit, and this technical process highlighted the true nature of photography: its mystery.

How was the process of whittling down your selection to 130 photographs?

There are some photographs I have taken that just stand out: they live with me, I know them, I remember what was felt, like we all remember certain people and certain experiences. Those are the photographs that are in my book. Of course there are others that I look at differently, 25 years later… I find an image that I missed, or I just didn’t see as I do now.

How did you change, as a photographer?

The Untamed Eye focuses on my early years of finding my photographic style, which led to a strong period when I had a lot of power and control — photographers had a lot of power and control, if you had something strong to say. Editors and clients trusted you to bring your vision to what they gave you. They allowed you two or three days for location scouting, three days to shoot a 15-page story. This was all understood: that if they required you to give them your vision, then you needed time to create. For me, this is critical. Today it is all about speed: more pictures, less time.

Do you think creativity evolves differently in different contexts? Having lived in various cities, do you “think” differently in Milan versus Paris versus New York?

I love this question. Absolutely, creativity changes in different contexts. When I first moved to Milan and then Paris, everything was new, different: language, culture, habits, ethics. I arrived alone, naive, curious, brave, lonely, afraid; I learned so much taking myself out of my comfort zone. I left NYC because I wasn’t happy with the pictures I was taking and I knew I had to go. In the 90s, the thing to do as a fashion photographer was to go to Milan and or Paris to get magazine work, to work on your style. The editors were so creative and excited that I came from NYC and I think they liked that I was a woman photographer; they were taken by that. After I edited, I would spend hours at a small Xerox store next to my Paris apartment and present a layout of my edit; some of the editors even let my layout be the final magazine spread. When I got back to NYC, it was hard; it was more conservative.

How does gender plays into the vision at large of a photographer? What do you think being a female photographer brings to a set?

Mostly, I think that a woman photographer has less room to make a mistake, and has more pressure on her to perform and be perfect. I was naive about being a female photographer; I just never thought that I would get a lower fee than a male counterpart, or that my gender could hold me back.