When Steve Schapiro died last January at 87, he left behind a wife, Maura Smith, and son, Theophilus Donoghue, and an extraordinary archive of prize-winning photographs that defined 20th-century American life. One of Steve’s final acts was a collaboration with Theophilus, a book of their photos, Seventy Thirty (Damiani).

The project took root back in late 2017 when Steve and Theophilus were driving across the country back to New York while listening to Shane Claiborne’s audiobook, The Irresistible Revolution: Living as an Ordinary Radical. Founder of radical faith organisation The Simple Way, Shane shared intimate and engaging stories of his mission to follow Christ, helping the most vulnerable through acts of love and faith. “Steve was just amazed by it,” Theophilus tells me. “Toward the end of the audiobook, he looked at me with this excitement in his face and said, ‘We have to work with this guy!’”

At that moment, an 11-month odyssey began, one that Theophilus likens to a “Peace Corps trip”. After completing the project, Steve was inspired to delve back into his archive and pair works he made throughout his storied career with Theophilus’s street photography to create a visual dialogue between father and son for Seventy Thirty. Seamlessly woven together, the book explores their shared passion for humanism and social activism, using the photograph as a means to foster intimate connections and explore meaningful truths — a lesson Steve learned studying with illustrious photojournalist W. Eugene Smith.

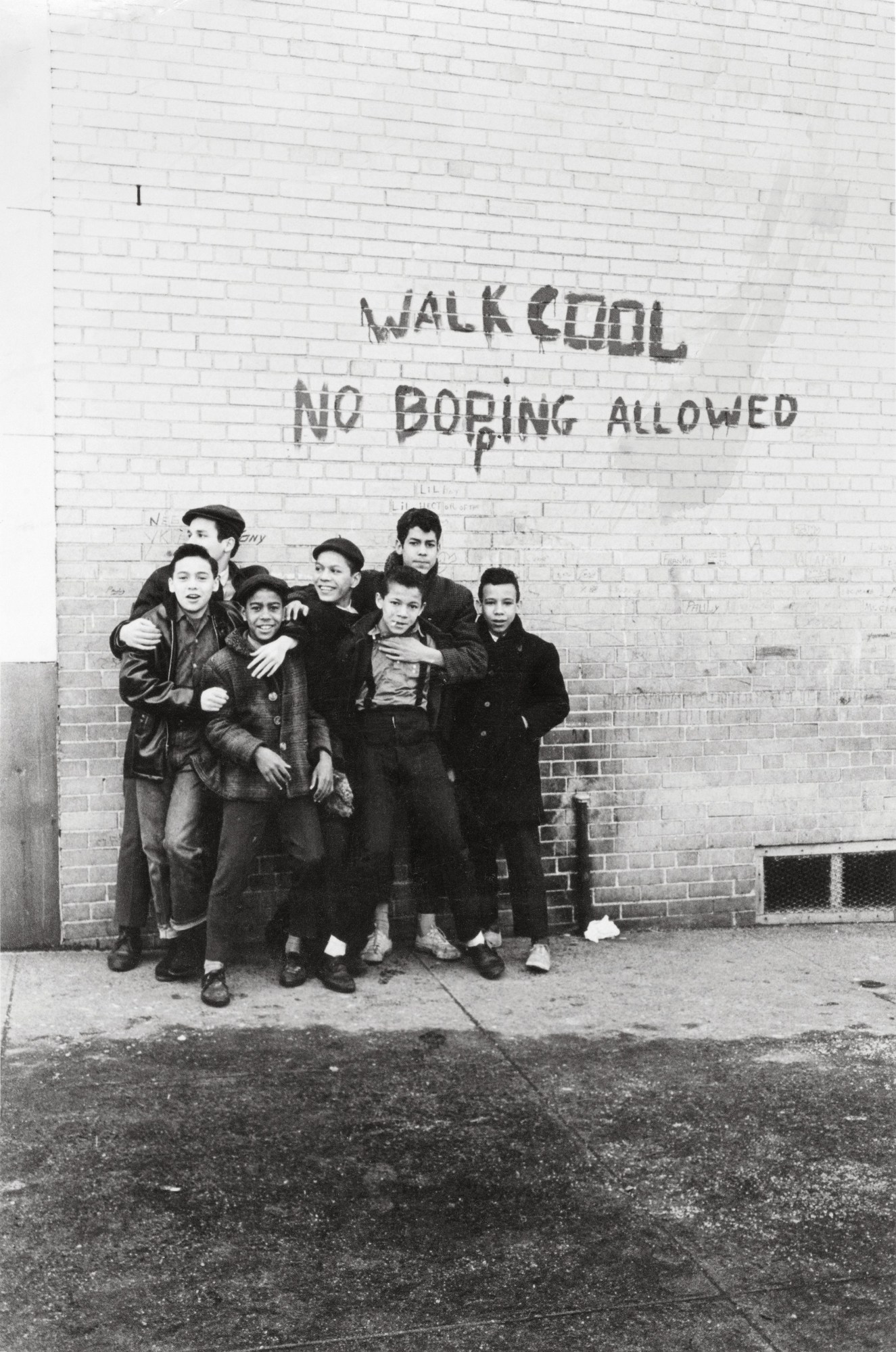

In 1961, Steve launched his career as a news photographer covering New York’s sizzling jazz scene. The following year, he read James Baldwin’s seminal essay, “Letter from a Region in my Mind”, when it appeared in The New Yorker and took its message to heart, using everything within his power to uplift the burgeoning Civil Right Movement. In 1963, destiny brought Steve and James together on a journey across the American South — two native New Yorkers representing the Bronx and Harlem, respectively.

Possessed with a keen sense of observation combined with a desire to go unseen, Steve moved fluidly in and out of different spaces. “He did not want to draw attention to himself or want to impose his style on anybody he photographed,” filmmaker Maura Smith, Steve’s wife, who worked closely with him throughout his career, tells me.

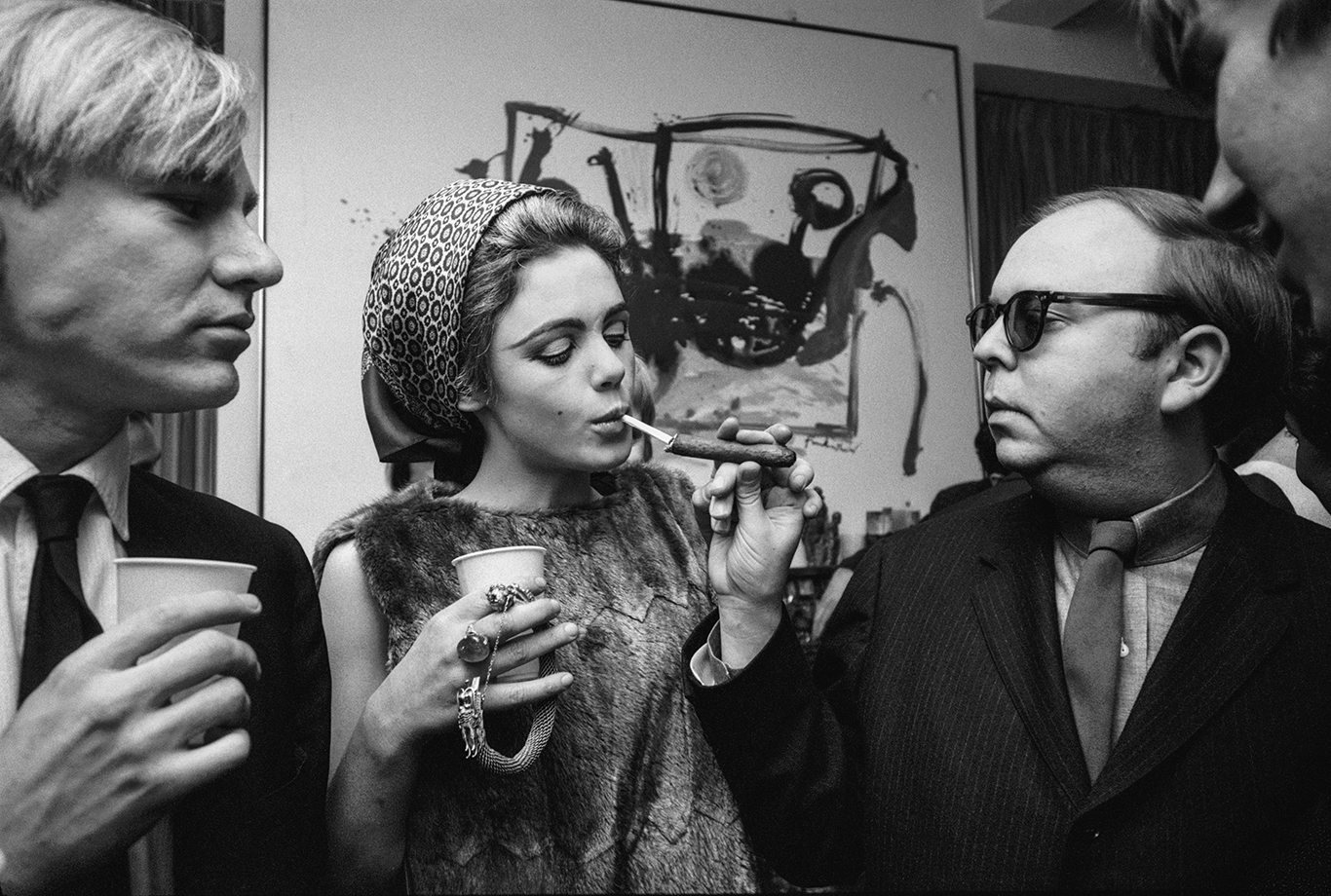

Blessed with an innate ability to attune himself to those around him, Steve was silent and unobtrusive, quietly reading the room. Aligned with the energetic frequencies of the people he met, Steve resonated with their vision and channelled it into his documentary and portrait work. Whether photographing a young Muhammad Ali playing with kids on a front porch in his hometown or Andy Warhol, Edie Sedgwick and Henry Geldzahler looking effortlessly glamorous at an art opening, Steve connected to the magnetic, majestic, and complex manifestations of humanity at its best.

Barbra Streisand recently gave her rare stamp of approval when she unveiled the cover of her official autobiography, My Name Is Barbra, on Twitter — Steve’s luminous portrait evoking the spirit of Hollywood’s golden age. It’s every bit Barbra, a diva who is among the last of a dying breed of celebrity, and Steve — who saw La Streisand as she saw herself.

And yet the portrait is wholly distinct from everything else Steve has done, be it his long-term collaborations with David Bowie, his work as a set photographer of Hollywood classics like Taxi Driver, or his lifelong devotion to issues of social justice. “From the beginning of his career, Steve has always been involved in politics,” Maura says. “Steve would always say ‘There’s no such thing as bad publicity’ because if you’re protesting something, people getting upset at you is a blessing because it gets noticed.”

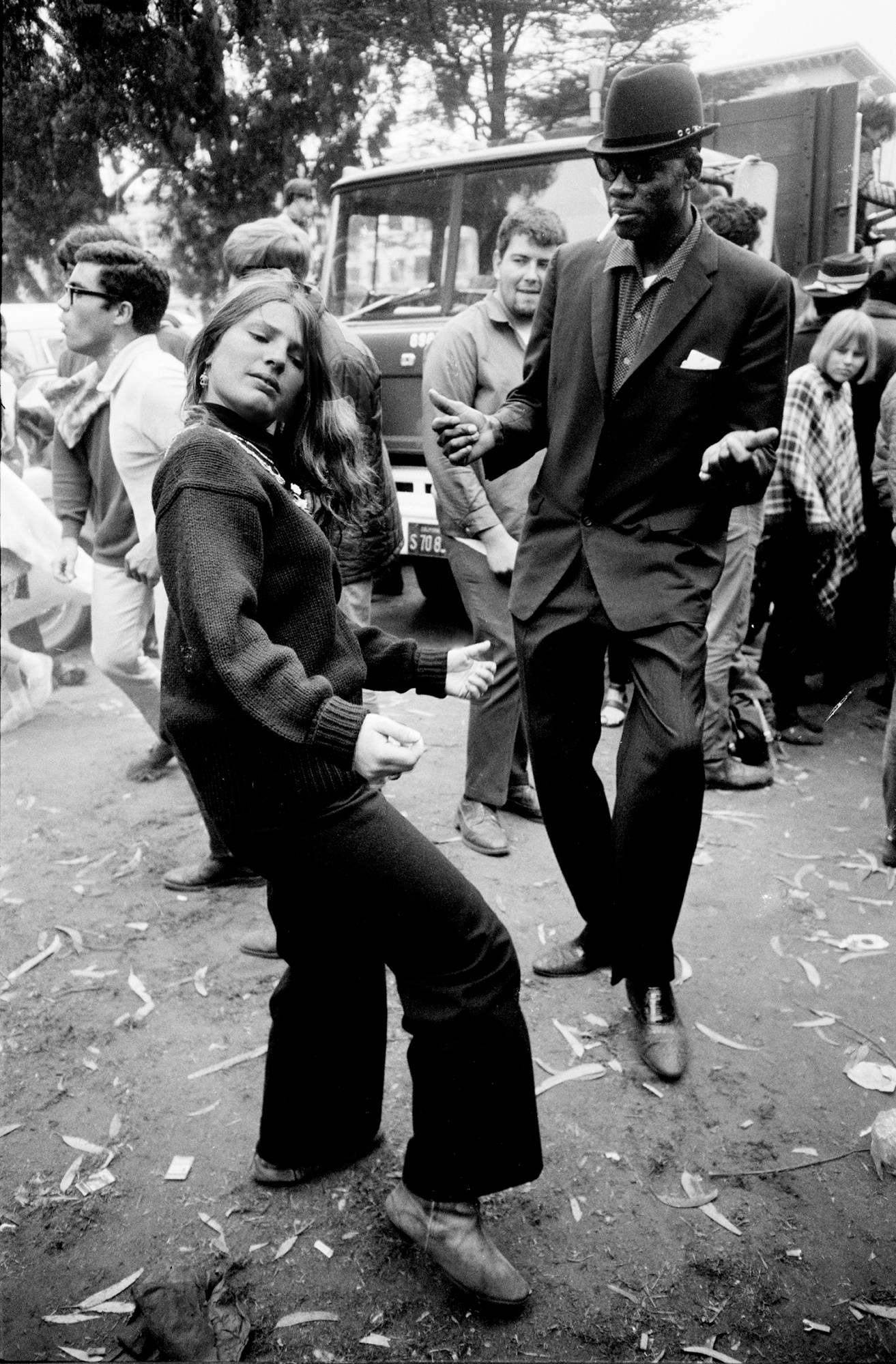

From W. Eugene Smith, Steve understood that photography could be used as a tool of activism and the media a platform to transmit the message far and wide — while also helping to shape the first draft of history. Whether chronicling the Civil Rights Movement, Robert F. Kennedy’s ill-fated 1968 presidential campaign, hippies in Haight-Asbury, or Black Lives Matter protests over the past decade, Steve passed along his love and commitment to Theophilus.

It was a bond they shared through Steve’s final days. “One of Steve’s last pictures was a portrait of Kurt Elling, a jazz singer out of Chicago,” Maura says. “We were all in the hospital, sitting around Steve’s bed talking, and he said, ‘Get my camera.’ He was lying in bed at a weird angle, took a picture of Kurt, and then asked for the other lens. Steve never wanted to retire. He got to live the life that is photography, forever.”

Credits

All images courtesy of Damiani Editore