If you don’t know Steven Traylor’s work, that could be because it’s quite hard to find. It’s not for lack of projects; he’s shot a cover for i-D’s Up + Rising Issue last summer, artwork for Earl Sweatshirt, and exhibited his work in LA and Berlin, but search his name online, and you might struggle to piece all this together at first.

Steven’s website and Instagram, nestled behind namedate.org and @name___date ___, respectively, feel more like streams of consciousness than conventional shop-fronts for his practice. Taking in a mixture of media; predominantly photography, but also video, collage and text, the 24-year-old rejects a single expression of himself and his community, instead crafting a more holistic vision of his life in Los Angeles; one as sonic as it is visual. “I was always curious,” he writes for his agency’s bio on him, “about why certain people in my community move the way they move.” Break beneath the surface of these artworks, soundbites, movie stills and bitmojis, and Steven’s curiosity begins to yield some answers.

Growing up in Mid City, a neighbourhood of Central Los Angeles, Steven stayed with his grandmother and spent his time outdoors 24/7, skateboarding, and in and out of art galleries. Too young for print magazines and too old for Instagram, his introduction to photography came, like many in that undefined grey area between millennial and Gen Z, via Tumblr.

“Tumblr was my school,” he says. “I was on some like… you would see a Helmut Newton image and I’m like ok that shit is sick, and then I remember seeing a Dana Lixenberg photo and I was like ‘Yo, what the fuck is this, this shit this looks like my auntie, and it’s shot in a beautiful way’. If you were to ask me around like 16 or 17 who was my favourite photographer, I’d probably say some type of Richard Avedon photo was like the shit for me, but then I’d probably jump to like Wolfgang Tillmans. That was what was so beautiful about Tumblr, it was a fucking smorgasbord of beautiful shit, and everything was at the same level but it was all coming from all these different vantage points.”

As a teenager he came to own an Olympus OM-10, a simple handheld 35mm camera popular in the 80s and, after failing to sell it on for much, began taking photographs with it. “My intention was never to use it,” Steven says. “I went to a few pawn shops trying to get it off, and they were like you ain’t really about to get anything for it, it’s $20. And so I just thought, I might as well learn how to use it. I always used to pass Samy’s Camera on Fairfax. I used to go to the repair floor like every other day and I’d be like ‘Yo, like what does this do? What is an aperture? What is a shutter speed? How do you exposure? How do you load film?’ I got a few pointers here and there and I shot like a thousand shitty rolls, and then I was finally able to use the thing.”

LA is an easy city to find subject matter in. It’s spacious, warm, and full of performances unfolding at every turn. Its sheer scale makes it impossible to pin down to just one monolithic thing, and Steven’s idiosyncratic work reflects that energy. “I remember my friend said something like, everybody has a different LA, everybody is experiencing the city very differently, you know. My experience growing up in Mid City, South Central, is a totally different perspective to someone who grew up in like Santa Monica by the beach. And my experience is different to someone who grew up in Imperial Courts, because that’s a whole different vibe. Being in project housing, and stuff, you know it’s easy to not leave your hub.”

Dana Lixenberg’s Imperial Courts – a project that began with Dana’s assignment to cover the riots sparked by Rodney King’s death in the early 90s and developed into a twenty-year photographic study of one of LA’s social housing projects – is arguably one of the deepest character studies into LA outside its most infamously exclusive neighbours. For Steven, the difference is it’s more about capturing it from the inside facing outwards. “I would love to do something like that, where I am revisiting these subjects,” he says, “but I shoot my friends and I do have recurring subjects that I come across, but those are homies, so it’s coming from a different place. I feel like I’m just documenting moments and just trying to capture my friends. You know just taking iPhone pictures of your homies. That’s what I do but with a more sophisticated camera.”

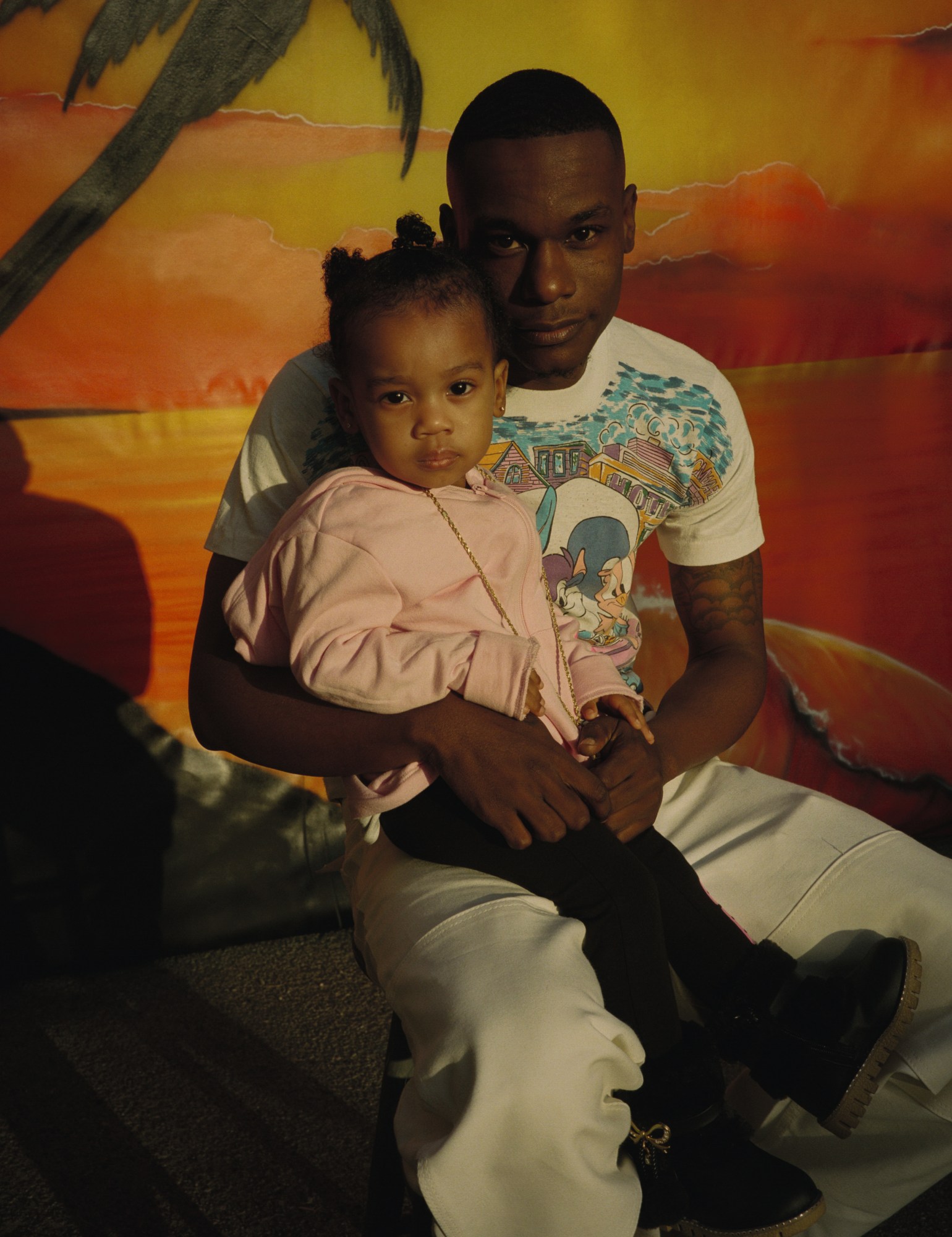

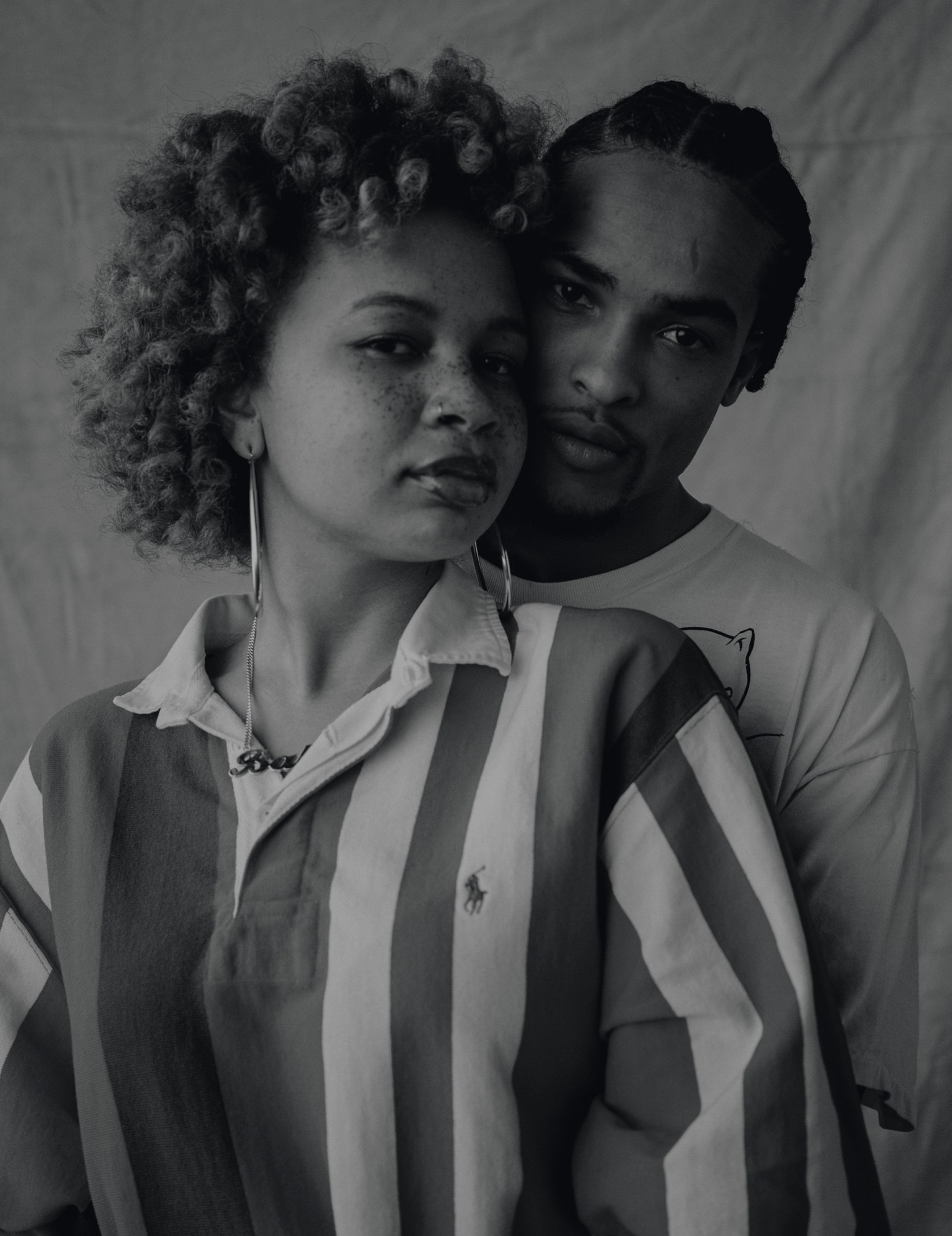

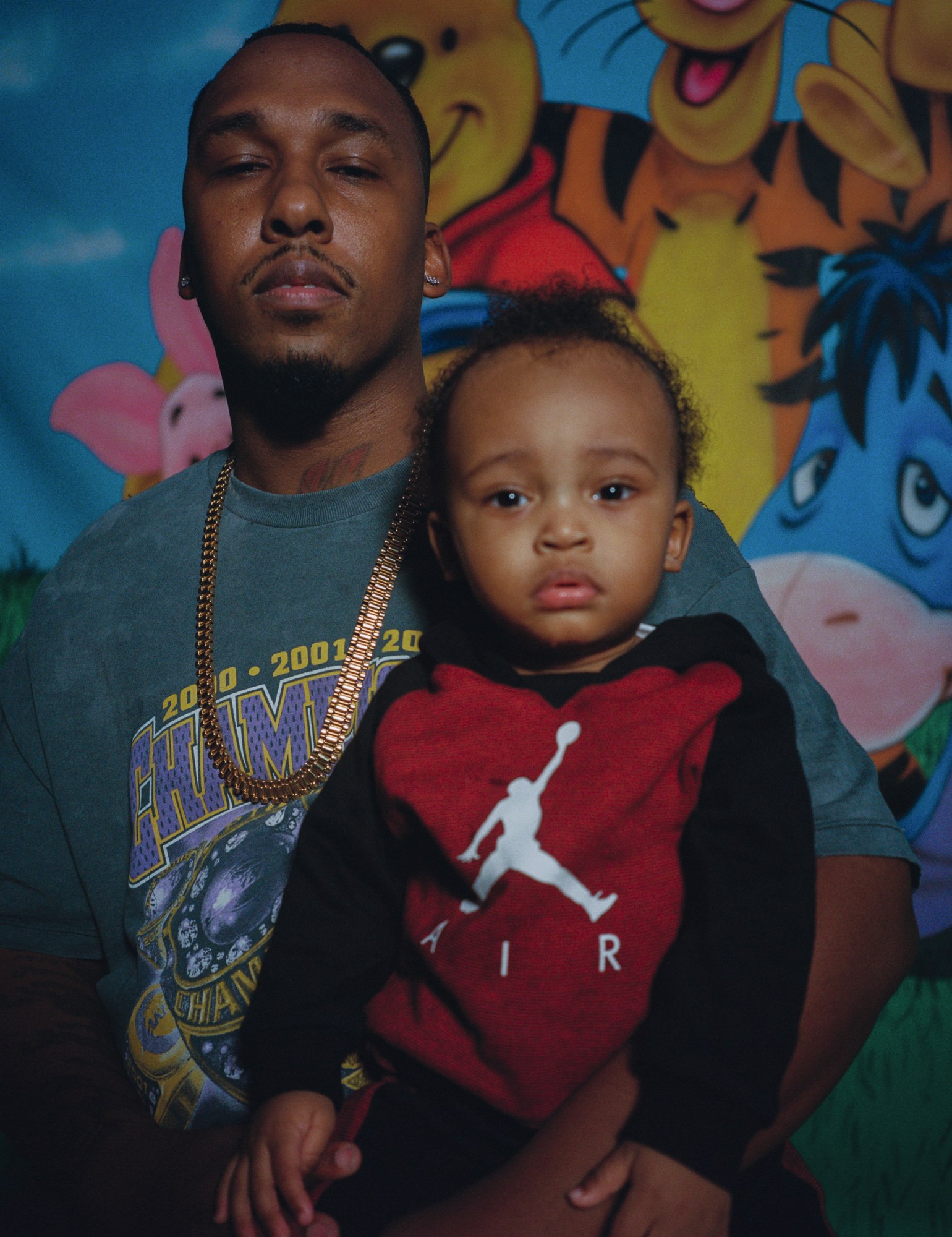

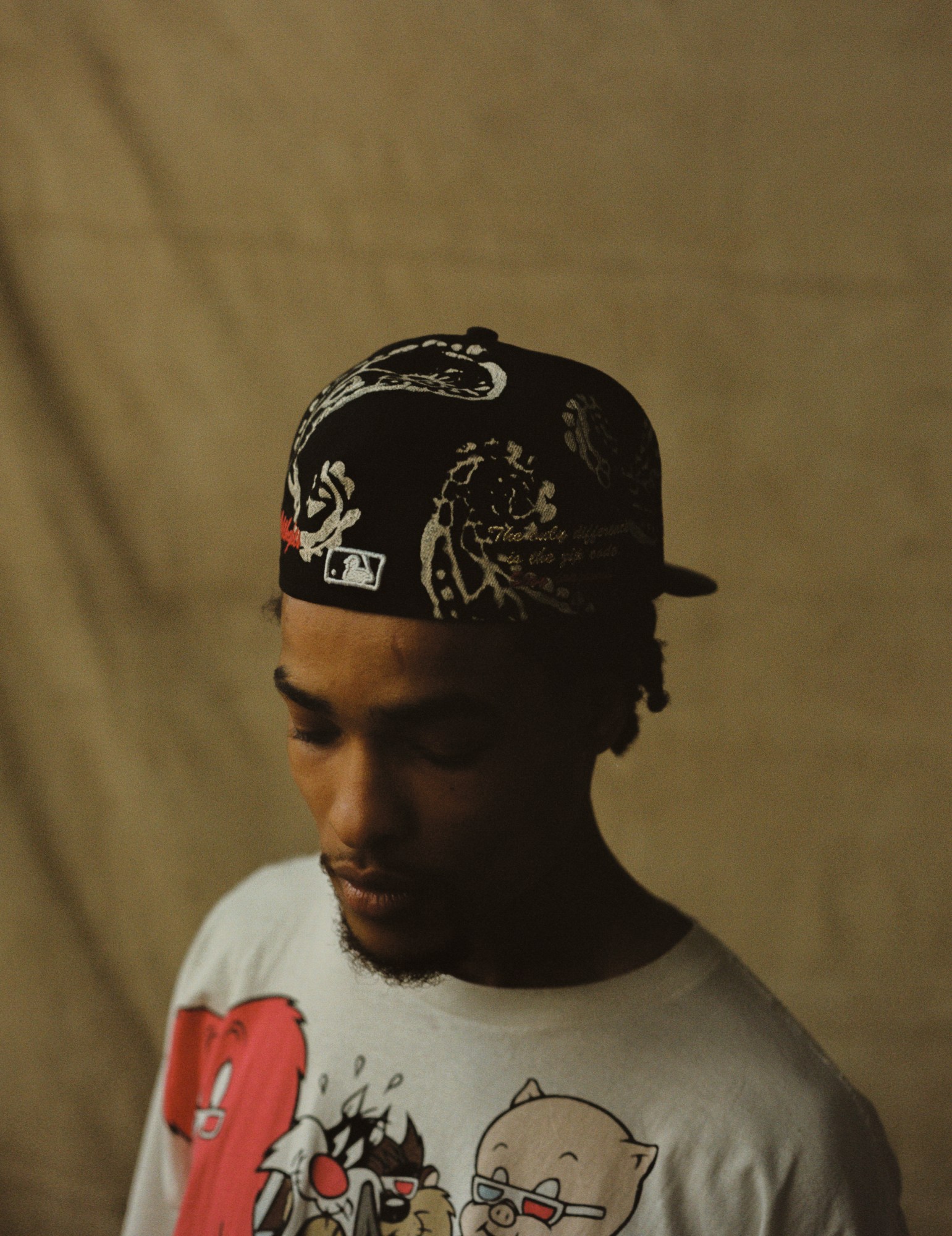

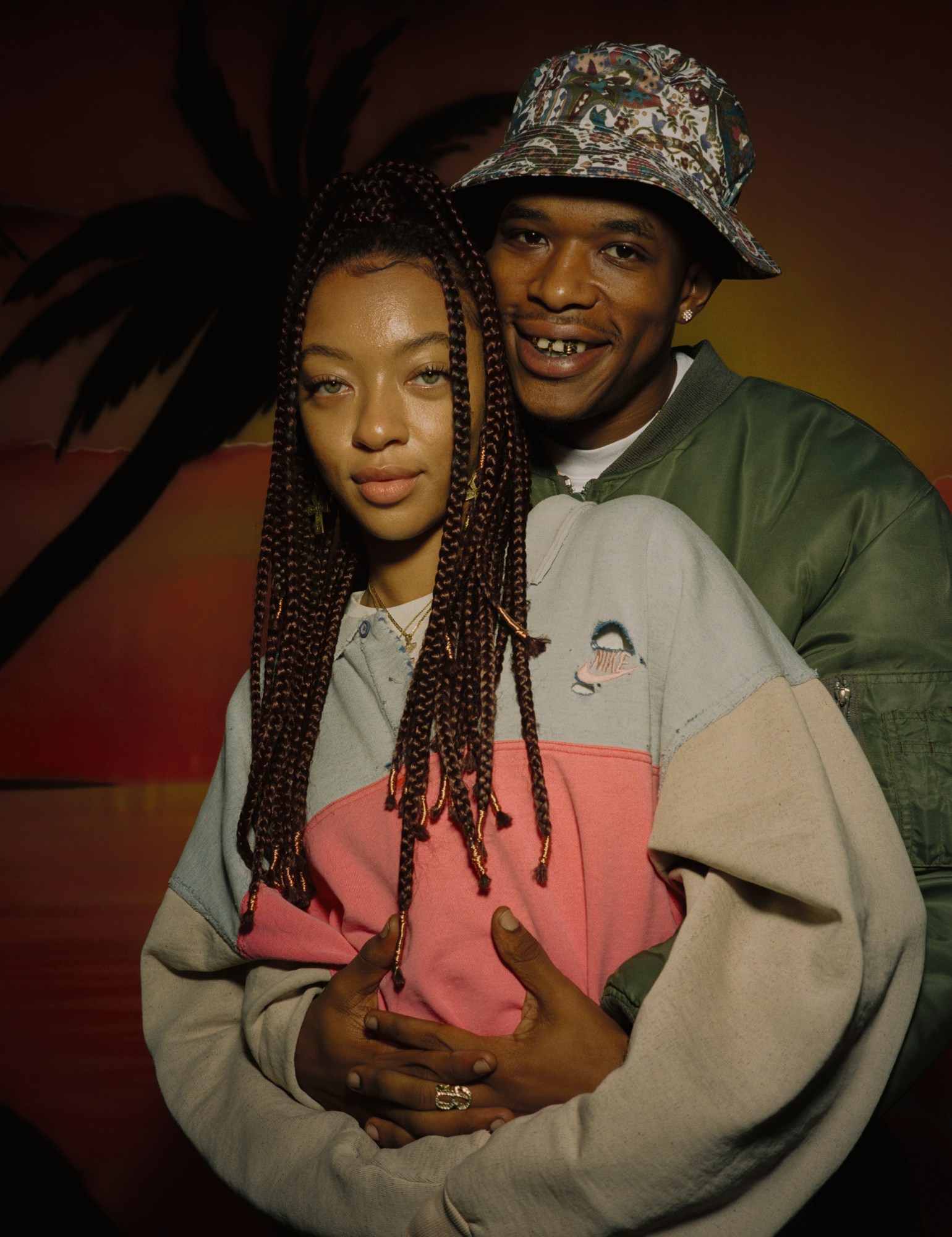

For this issue, Steven focused on the literal meaning of family and community, placing his subjects – some known to him, others not – in a traditional portraiture setting, the kind taken against tacky airbrushed backdrops in the mall. It’s a celebration of love: “I just wanted to make my own version of that. Seeing healthy images of love, I feel like that shit is so important to the Black community,” he adds. “I feel certain images like that we latch on to are not healthy. So I want to be able to just represent something that’s like – I don’t know, it’s like you can’t deny it’s like ‘Yo, it’s beautiful’.”

As we talk, America descends deeper and deeper into its existential crisis in the capital. But two and a half thousand miles away, Steven feels removed from this. “I’m away from D.C. and all that stuff, so it’s like I don’t really feel it that much. And I’m just trying to stay away from all that drama and all that. I’m with my family, you know, just chilling, watching movies, I can’t complain, I’m blessed.”

Credits

Photography Steven Traylor

Styling Tamia Mathis

Hair and make-up Rachel Lee Wright at MA+World Group using Tangle Teezer.

Set design Gille Mills at 11th House Agency.

Airbrush artwork backdrops Sketch Airbrush

Production Imani Lindsey for Camera Club.

Special thanks Nick Shaya, Bob Melet, Icon LA and Chroma Center.

Models Maliyah, Harmony, Dyme, Marz, King Mel, Dalis, Taylor, Mikhayl, Jasmine, Shavo, Barrington, Zolee, Watts Homie Quan, Baby Givens, Huey Briss and Brielle.