Andy Warhol reportedly asked the artist Richard Hambleton to sit for a portrait on numerous occasions, but he declined every time. As much a fixture of New York’s 80s underground art scene as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, Hambleton was much less concerned or interested in the cult of celebrity than his contemporaries. Remaining largely out of the spotlight throughout the 80s, and disappearing completely from the public eye by the 90s, for some, their introduction to Hambleton’s life and work will have come posthumously, following his death in October last year. To others it may have been via Shadowman, an award-winning documentary on his life that premiered a few months prior to his death. But for most, the name of Richard Hambleton remains unknown. Yet his influence is everywhere.

Hambleton was born in 1952 in Vancouver, Canada. He studied at the Vancouver College of Art and gained notoriety after graduating for his life-sized white-painted human outlines on pavements that mimicked those done by the police in murder investigations. Creating a pseudonym for the private eye investigating these fake crimes, R. Dick Trace-It, Hambleton created over 4000 fake FBI wanted posters for his fictitious murderer, Mr Reee. He travelled across Canada and the USA throughout the 70s, painting over 620 outlines along the way, and gaining infamy amongst art critics and local police departments alike, before settling in New York City in 1980.

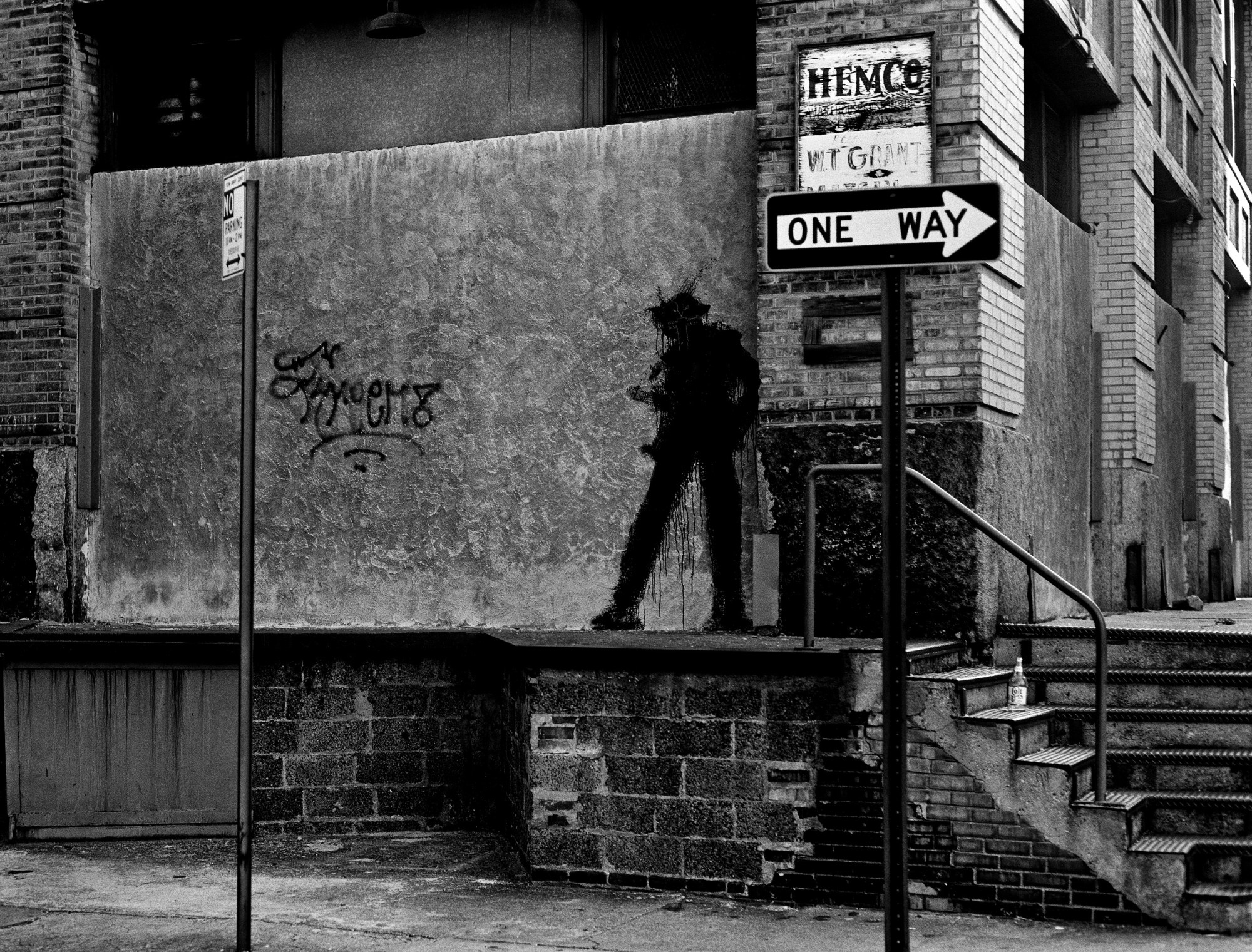

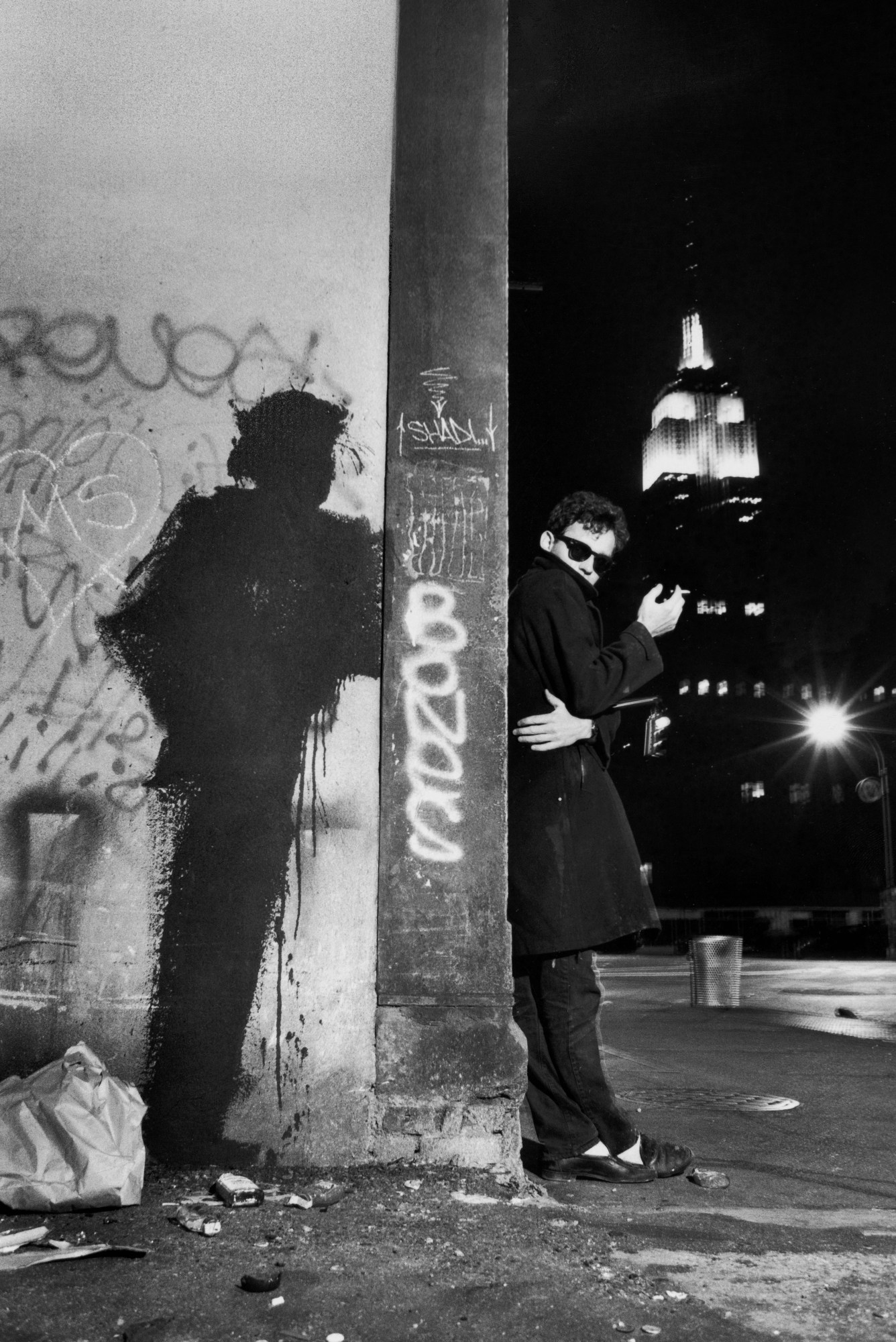

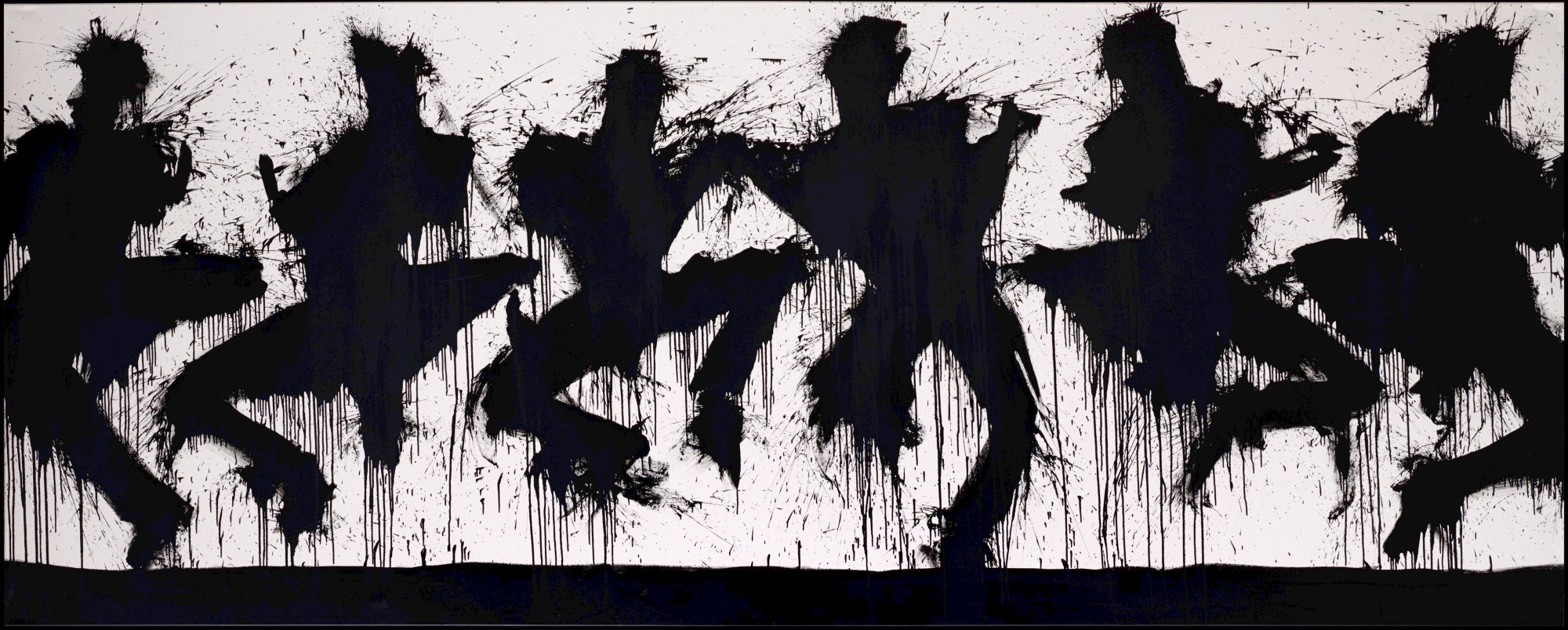

Once in NYC, Hambleton continued his series of white cut-outs, but became better known for his menacing black silhouettes on the graffitied walls of New York’s labrinth streets and alleyways. These ominous, dark “Shadowman” paintings, some lurking on street corners, others elevated in the air as if jumping out at you, were splattered against the walls with a frantic verve that spoke to the culture of fear and tension spreading through the city as crime rates soared. “I painted the town black,” Hambleton told People magazine in 1984, as cited in his New York Times obituary. “They could represent watchmen or danger or the shadows of a human body after a nuclear holocaust or even my own shadow.” The Lower East Side became the canvas on which he created this nihilistic vision of the world and, as NYC’s street art became the backdrop of a creative revolution, it was Hambleton’s name at the top of the bill. When the International Herald Tribune did a piece on the boom in graffiti art in 1983, it was Hambleton, not Basquiat or Haring, who had an accompanying image.

By the mid-80s, Hambleton was travelling between the USA and Europe, where he exhibited and sold some of his work, and painted his infamous murals across the streets of Paris, Venice and, most notably, against the Berlin Wall. At this time, his work outsold that of his contemporaries, but, perhaps where the legacy of these artists take such different paths, is that Basquiat and Haring died, while Hambleton lived.

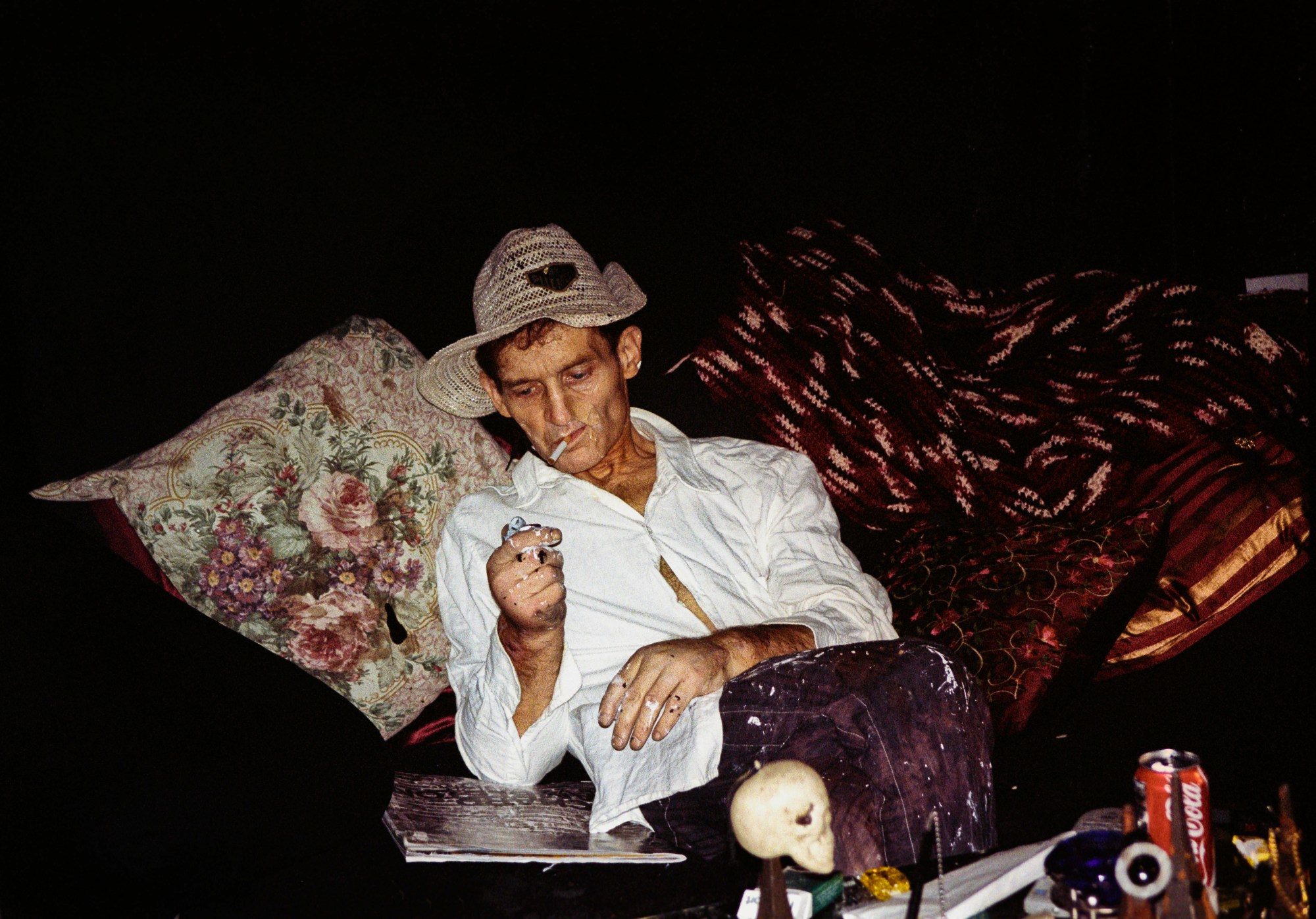

But addicted to heroin, haunted by the deaths of many friends during the AIDS epidemic, and completely disenchanted with the artworld, by the 90s Hambleton had retreated entirely from the public eye. His style transitioned from hype-creating street art to more considered, detailed landscape paintings, much to the dismay of the New York artworld. Some say this was tied to his drug addiction, drawing parallels between the rich red and broad brush strokes of some paintings and the heroin coursing through the blood in his veins — while others say that he simply wanted to progress as an artist.

Over the next three decades, his origination and innovation on the streets would go on to influence prolific artists like Banksy and Blek le Rat, yet his work never quite reached the dizzying commercial success and pop culture fame as Basquiat and Haring went on to. “Basquiat and Haring always had a lot of respect for Richard because he had paved the way for their commercial success,” says Andy Valmorbida, a friend of the late artist and collector of his work. Co-curating a new display on his work at London’s Maddox Gallery, for Andy, Richard’s appeal lies partly in his elusiveness. “They traded amongst themselves — Basquiat had a Hambleton collection, and vice versa. But Richard didn’t sell himself out like Basquiat and Haring did in the 80s. At the time, more gallerists and collectors wanted Richard’s work than they did Basquiat or Haring. To me his work is some of the best artwork I have ever seen, especially of any street art. The gesture of his brushstrokes was unparalleled — his style and technique was so strong and unique it identifies him apart from anyone else.”

For Maddox Gallery creative director Jay Rutland, a year after his death, and four decades after he began painting the town black, the work he created couldn’t be more prescient. “I probably discovered Richard much the same way most people do, people talk about him in the same breath as Basquiat and Haring, but he’s a much more mysterious figure. It’s like he’s infamous and unknown at the same time, and that fascinates me. My god, in this day and age he’s more relevant than ever. We’re so saturated with our news cycle, and social media and one story more shocking than the next — and Mass Murder and Shadowman speak to that part of our psyche, the part that’s unsure, and doesn’t know what’s around the corner — it touches the same nerve it always did.”

In our perennial cycle of references to a golden era of counterculture, Richard Hambleton’s work deserves an expansive exhibition as much as Basquiat deserves four months at the Barbican. A retrospective of his life may not come with quite the same same glitz and glamour of his contemporaries — the accompanying polaroids of Warhol and Madonna — nor will his legacy be forever enshrined in the hallowed halls of 80s New York by an untimely death. But his impact is everlasting. “He changed New York,” adds Jay, “He changed art, full-stop.”

A display of limited edition Richard Hambleton prints will be on view at Maddox Gallery, Westbourne Grove on 18 September 2018, 112 Westbourne Grove, London W2 5RU.