Not more than 20 years ago, before the arrival of Boxpark, Shoreditch House, Aesop stores and organic supermarkets, Shoreditch was a run-down, crime-ridden non-location on the urban map of London. However, when a bunch of young artists later to be known as the Young British Artists graduated from Goldsmiths College in 1989 and were looking for spacious and cheap studios, the former industrial area became the absolute embryo of artistic production in London. With Hoxton Square as its epicentre, the young art scene brought with it a new wave of vanguard galleries, nightclubs and gay bars – but unfortunately, also a wave of violent gentrification hungry for the ‘new’ ‘cool’ ‘urban’ environments. Today’s Shoreditch is a grim emblem of the increasingly rapid gentrification London faces, in which authentic local history and radical creativity is sold as chic aspirational tropes.

However, as Studio_Leigh opens only a stones-throw away from Hoxton Square, Shoreditch is once again providing exhibition space for some of the most exciting young talents in the London art scene. Situated in an old varnish factory, the exhibition space and studio provides three floors that showcase new and emerging London-based artists working with all ranges of media, from sculpture and painting to video and CGI. But what makes Studio_Leigh, whose inaugural exhibition opens with a group show of 27 artists: the project facilitates the production process of artist’s work by finding and matching British craft workers to each artist, including glassblowers, electricians, woodworkers and seamstresses.

The exhibition space is spearheaded by Central St Martins alumna and former Mario Testino art director Tayah Leigh Barrs. “Studio_Leigh formed out of my own interests as a cross-over between creative practices,” she explains. “I’ve always been intrigued by the way in which we approach objects – art or otherwise.”

Linking conceptual artist with specialised craftsmen, Studio Leigh attempts to merge the awkward gap that has existed between art and design for over a century. The brief for the first exhibition was to create works that could “function,” in the broadest sense. Since art for art’s sake became the ethos for the Aesthetic Movement in the 19th century, art has slowly detached itself from any “real life function” – accentuated not least by the conceptual art of the 60s that sought to completely remove itself from a form of art that could be bought and speculated. Finally, with the internet offering itself as a completely immaterial sphere of creativity around the millennium, there seems to be little reason for today’s artists to be concerned with ‘functionality’ or ‘physicality’. Yet perhaps, that’s exactly why we’re seeing more and more artists returning to creating objects these days.

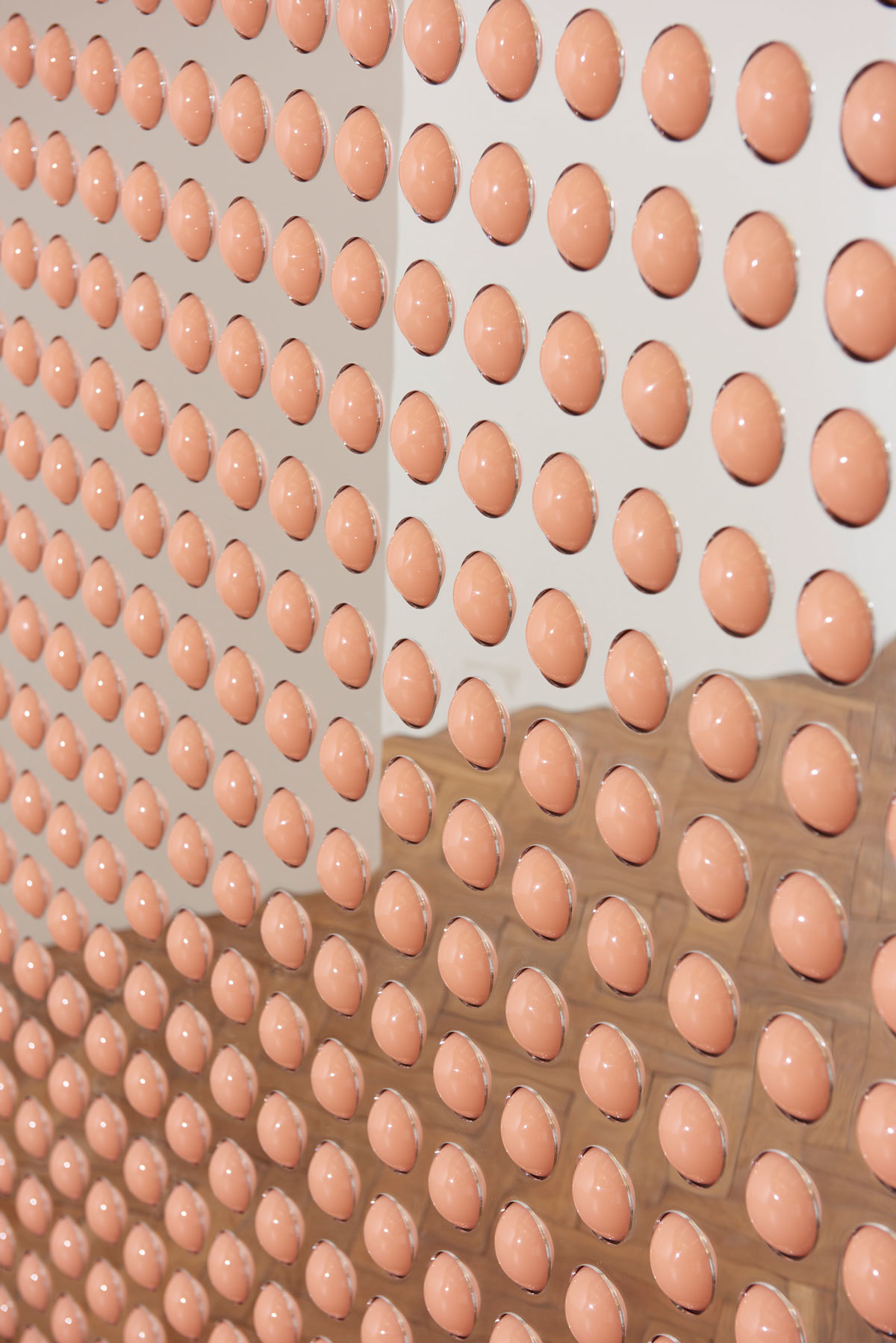

In a time of virtuality and mass-production, there’s an immediate enjoyment in simply encountering an object that has been carefully crafted by hand. Aaron Angell has, with specialist help, built an actual rowing-boat, complete with anchor, brass rowlocks and leather oar cuffs.”The project enabled me to make something that I wouldn’t put in a normal exhibition of my work,” Aaron explains, “I think most of the artists involved with the studio would say it has been refreshing to make things for this interstitial space.”Central Saint Martins graduate Ophelia Finke, who installed a jeep in the desert at her graduate show in 2014, extends her fascination for Saharan landscapes through a hand woven sand-looking wool rug, with the trace of a bike wheel seemingly imprinted upon it. The exhibitions invites the viewer to feel, and tactility runs through the 24 works that constitute the exhibition. Florence Peake invites viewers to get a proper art rub-down on her massage ball-covered wall surface at the back of one room; Nicolas Deshayes wants you to warm your hands on his cloud-looking sculpture, Filth Takes Off Its Shirt, installed as a fully-functional radiator on the wall of the gallery.

The influence of design, and particularly fashion, is certainly felt, with many works borrowing and questioning the language, logic or even format of the creative industry. The sculptor Richard Healy, who graduated from the RCA in 2008, presents a fully-knitted sweater with appliqué typography, or in the work Softness, by Cècile B. Evans, which offers to the audience samples of an actual cosmetic oil that she produced after advertising it in her 2014 video Hyperlinks or it Didn’t Happen, a video work that discussed the representation and employment of digital avatars (and featured computer-animated Japanese singer Yowane Haku and the “ghost” of Philip Seymour Hoffman. By mimicking the language of fashion PR, Evans exposes the surrealism of advertising, and how virtual characters might be (ab)used to promote physical objects – and asks, what comes first; the object or its commercial representation?

For all it claims to “reality”, the iconography of the internet is unescapable, and overall, the exhibition articulates the tension between the virtual and the physical that is experienced in our digitised world. Digital artist Adham Faramawy has for long explored the aesthetics of the spa, the beauty industry and virtual liquidity through his psychedelic CGI videos, but with his piece Hyperreal Flower Blossom his virtual perfume scent suddenly takes a tangible and tactile form. Indeed, it’s hyperreal to be able to smell a digital idea, and what does it say about how we continue, despite virtual mobility, to use our bodies to decode and understand certain concepts? Harry Burden’s Body Double-Double Bodies Grekko takes that translation even further as he, with the help of a professional 3D printer, copies chipped vases from three different historical periods (Ancient Greece, Japan and 17th century Versailles) in the Tumblr-looking material ‘absolute purpeleen’. “I was interested in the functional aspect of the project because these concepts mirror interests in my own practice. They provide a counterpoint to the virtualisation and un-physicality of the technological experience,” he explains.

The inaugural show at Studio Leigh indicates two things: a return of young art to Shoreditch, and a return of materiality in young contemporary art. Both are somewhat precarious propositions, given that gentrification and the creep of the digital world IRL, is unlikely to stop, and impossible to turn back.

But given the means and opportunity to approach new and old crafts with a fresh and conceptual approach. Studio Leigh is offering a platform for emerging art to be viewed and sold, while reintroducing us to the appreciation of labour-intensive craftsmanship in contemporary visual culture.

Credits

Text Jeppe Ugelvig