From the time we’re old enough to see our first Disney film, we’re taught that all of your wildest dreams can come true if you’re pretty enough. And yet when I receive a DM on Instagram from a sugar daddy offering $5,000 a week in exchange for nothing but “companionship”, my first thought is, “must be a scam”.

When the message comes through I’m at the hairdresser’s, where I am, yet again, dropping €200 to look cute. I look at my reflection, thinking: I would love someone else to pay for this. I decide to play the game and see where it goes. If nothing else, this’ll entertain me for the next hour.

Making money off my appearance never seemed realistic for me personally. But the deeper I got into my conversation with Daddy Shawn, the more tangible the idea became. But it turns out he was using psychology to manipulate me, and he’s not alone in the scam.

“That’s a very sweet offer, how exactly would this work?” I replied. Shawn replies almost immediately: “I’m seeking… someone loyal and trustworthy whom I can share my thoughts and feelings with, someone to give me attention and in return for your spoils and support, as my baby all daddy requires from you is your attention and advice, Can you do that baby <3?”

I can tell this isn’t a bot, but the choice of words is surreal. Complete with poor grammar and hackneyed phrases, Shawn’s script uses textbook kink language: “Daddy got you”, “can you be honest, loyal and trustworthy”, “never doubt or argue with me”, “let me spoil you”, and so on. What’s equally interesting is my response. I naturally slip into character, acting naive and submissive. “I’ve never had a Daddy before” I reply. It was a live action role play over text.

A friend and real-life sugar baby explains that this vocabulary is pretty common. “I do say things like, ‘Daddy can you treat me?’ or they’ll say things like, ‘Do you want to be spoiled today?’,” she tells me. “When we speak, I’m just mirroring them and trying to figure out what they want. One sugar daddy I dated was so shy and nervous, I would never call him ‘Daddy’… Oh my god, it was just not the vibe!”

‘Mirroring’ is a term used by psychologists to describe our unconscious imitation of body language, facial expressions and tone of voice during social interactions. While I was aware that I was indeed mirroring Shawn, I wasn’t entirely sure why. Reading up on it, it started to make sense. “Participants who had been mimicked were more helpful and generous toward other people than were non-mimicked participants” one study wrote. Put simply, I was mimicking Shawn’s language to increase my chances of receiving money.

And in some ways, in such a transactional relationship, it might even feel odd to be your real self. In my conversation with another sugar baby, non-binary artist and model Isaac Looker, we discussed the performative element of this dynamic. “My sugar daddy found out about me when I was touring with my band. They later told me they used to buy all our records, and come to every show. So, it was as a performer that they were interested in me,” they tell me. “And our relationship is something of a performance. I guess they are aware of it and maybe that’s part of the fantasy as well… that fictionalised person who is unrealistically amazing.”

So, Shawn’s language choices were not necessarily a red flag. But the repeated demands that I be “honest, trustworthy and loyal” did seem suspicious. It was clear Shawn wanted me to keep our conversation secret. Another study showed that people are more likely to agree with someone’s argument if that person selectively repeated information in favour of it, a technique also used in political speeches. Repetition was just another manipulation tool.

Speaking to other people who had been approached by fake daddies, I started to notice a pattern. The scammers were following a formula. Whilst there are more current studies on persuasion techniques used in scamming, Robert Cialdini’s 1984 book The Influence: Psychology of Persuasion kept coming up. Despite its age, it continues to be one of the most widely sold marketing psychology books today. In fact, Robert Cialdini himself is far from retired, advising both Obama and Hilary Clinton on their presidential campaigns. In Influence, he breaks down the key principles of persuasion: reciprocity, scarcity, authority, commitment and consistency, liking and consensus.

Shawn employs a few of these himself. The first is ‘authority’ — we tend to believe authority figures, so the scammers pose as someone older, richer and more experienced, and significantly… male. By targeting women or femme-bodied people, they play into our deep rooted gender bias towards male opinion. The second is ‘liking’ — we are more likely to go along with something if we like the person proposing it. Shawn takes care to show he is a ‘nice guy’; “I actually started this financial support to assist student and ladies with small income and also single mothers who can’t pay of there bills <3” This is followed by his sob story; a hard upbringing and a dead wife. We dutifully reply with condolences. The third is ‘consensus’ — we are genetically programmed to trust our tribe, so seeing testimonials from others is reassuring. The scammer sends photos of ‘themselves’ and ‘their babies’ posing next to new cars or holding large wads of cash. Saccharine voices coo ‘Thank you Daddy <insert name>’ through their selfie-screen.

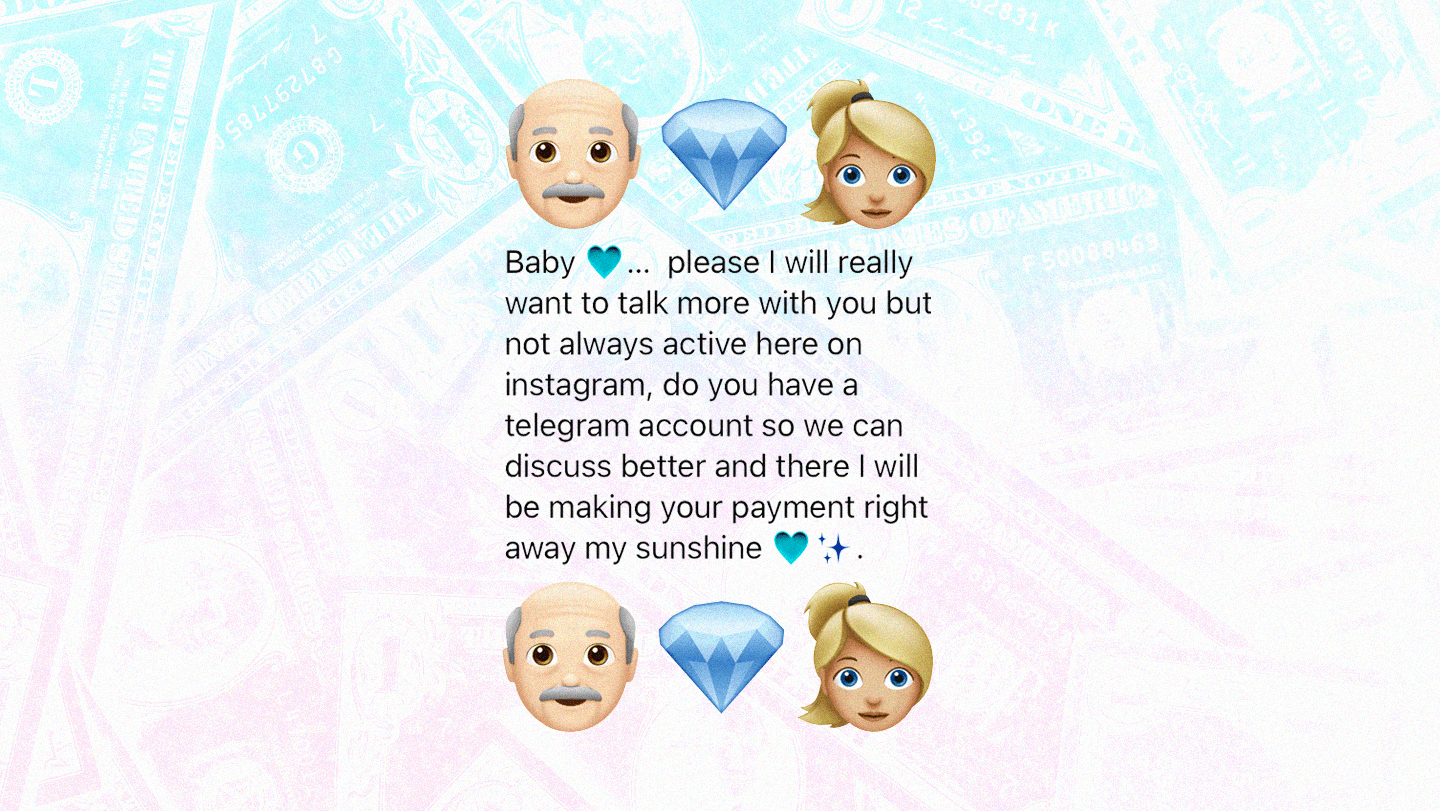

At this point even my cynicism was waning. Could this be for real? But then Daddy Shawn asks me to send photos of myself in return. I politely explain, no pics before payment. “Done baby <3” he says, with a screenshot of the PayPal payment of $5,000. I notice something usual: “Payment method: Voucher”. A quick check on PayPal FAQs confirms that PayPal doesn’t use vouchers for international transactions. I see where this is going. “So baby <3. You’ll have to purchase a $100 international voucher to verify your pending payment”.

I respond that this is not how PayPal works. “What are you trying to say,” he replies “that I am lying to you?”. The weirdest thing is, even though I know I’m being scammed, the accusation stings. It feels like, over the course of the conversation we’ve built some kind of relationship. I start to feel uncomfortable. I screenshot the chat and blocked him.

But could the offer of $5,000 a week for doing, well, not a lot actually, really exist? In a few words, my sugar baby friend debunks the fantasy. “There is a dream of just having a sugar daddy and not having to do anything in exchange, but you have to put a lot of effort in. At the very least it requires constant texting and regular calls,” she explains. “It can be very emotionally draining. Usually the best outcome is that they just want sexy videos and nudes, but even that is rare, and most of the time it only lasts so long until they want something physical.” Both sugar babies I speak with point out that this is sex work. It’s a saturated market and no one is handing out cash for free. Still, I had to admit, I enjoyed the temporary delusion. Part of me really did hope that money would appear in my PayPal.

But all the same, I wasn’t pissed off, just curious. Moments after I unblocked Shawn asking if he would be up for speaking to me for this article, the chat disappeared. Whilst it’s more comfortable to imagine a video-game obsessed hacker in their bedroom, the sad reality is that many of these people are manipulated and controlled by organised crime groups or exploited into low paid work. I really had no idea what Shawn — whoever he was — could be going through.

The ‘sugar daddy scam’ doesn’t just live on Instagram. It’s historically been more commonly seen on dating apps such as Grindr and Tinder; places where people go specifically looking for sex and relationships. By definition, these platforms might make us more vulnerable to “love” or “romance” scams. So, the move to Instagram is interesting. Whilst not designed for dating, its tendency towards ‘self advertising’ makes it normal to be approached by admirers there. The idea that “girls and women” are being socialised to see ourselves through the eyes of others, “as objects to be looked at and evaluated” seems to extend to all its users. In commodity culture, we have become commodities. A product to be marketed, bought or sold.

Below the surface of the scam, Daddy Shawn had tapped into the depths of the modern day psyche.