In a plain white stairwell in Harajuku I join a queue of small Japanese children and their parents. We’re waiting outside the recently opened Kawaii Monster Café that was dreamt up by artist and designer Sebastian Masuda, a man better known for his work with pop star Kyary Pamyu Pamyu.

Once inside I’m served by a waitress in a ghostly Miss Havisham uniform of Victorian lace and pale mauve fluffy wig. She sits me under a canopy of glowing translucent tentacles at the bar. Bottles of Moët are available for 11,000 yen (around £65) alongside speciality drinks with names like “Druggy Cocktail (Noctilucent)”. On top of a glowing fridge of Jägermeister sits a model of the Kawaii Monster. It looks like a melting purple Cookie Monster and has a crazed look in its rolling eyes.

Sat next to me is a teenage girl wearing a white varsity sweatshirt with the slogan “Dedicated Dwarf Bravery” and enjoying a plate of rainbow-coloured pasta with smears of what looks like paint on the side. Around the corner in the main room is a gloopy cartoon architecture of magic mushrooms and a carousel. The DJ booth is unoccupied but has a large tail.

On my way out I’m handed the café’s “Fall in Stomach” loyalty card, and the whole experience really is like being swallowed by a slick and enjoyable monster. Inside its belly a comforting soundtrack of quiet Japanese house music casts a Balearic calm, a mildly psychedelic sunrise-over-Ibiza feeling across proceedings. This place is a sweet pop gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art that surrounds us and fills everything.

Next stop is Akihabara, which is famous for its electronics superstores and maid cafés where young Japanese women dressed as French maids serve you in a saccharine, obsequious fashion. It’s a strange and unsettling place. New Type, where I’m headed, is hidden up a dingy staircase on a side street and is slightly different from the other maid cafés because all of the maids here are actually young men: in plaid dresses and flat court shoes, with freshly straightened wigs and fox-ear headbands. It’s only open in the evenings and is more of a bar than a café. I’m crammed in alongside the other customers on a narrow bench and one of the maids brings me a small bowl of pickles.

It’s a mixed crowd: a young couple drinking together; a middle-aged man chain-smoking on his own in the corner; a couple other men that spontaneously begin playing on Rubik’s cubes, and soon abandon them. Another customer walks in, in drag. She’s dressed up as a pink Harajuku girl with a scruffy wig and a toy Totoro covered in cheap jewellery hanging from her bag. She sits next to me with a melancholy air. She is completely alone and tells the maids that it’s her birthday and they don’t bring her a free drink or a cake or anything. However she is allowed to buy a Polaroid with a maid of her choice, who poses with her and afterwards scribbles over their picture in coloured pen, and she seems happy. I buy one myself and it costs 1,000 yen, just over a fiver, and I’m happy too. It’s a lovely evening. New Type is an unusual sort of bar, one that has a focus on awkward and theatrical interactions rather than intoxication, and sure it is rather lovelorn and has something of the psychosexually muddled, dystopian broken society about it – but then so do most bars anywhere in the world.

Next stop is a mistake of sorts. Hidden down a nondescript backstreet in the very heart of Tokyo, close to the infamous Shibuya Crossing, is Sakuragaoka Café. I’d read that it was a “goat café” but it’s nothing like what I expected: no teacup-sized baby goats jumping around between the tables and licking my face, no waiter goats bringing me coffee. There is only an old white goat named Sakura (Cherry Blossom) and she lives in a little house out front. Sakura has a salt lick inside her ornate cage and I have a Spaghetti Carbonara inside the premises. It’s a warm, comfortable Mediterranean kind of a café, and bustling with good-looking locals. I hardly even notice that there is a goat peering at me through the glass. But this is a restaurant after all, and it turns out you can only really frolic with goats, and dance about and drink wine with them in classical mythology; although you can make a reservation to take Sakura on a walk.

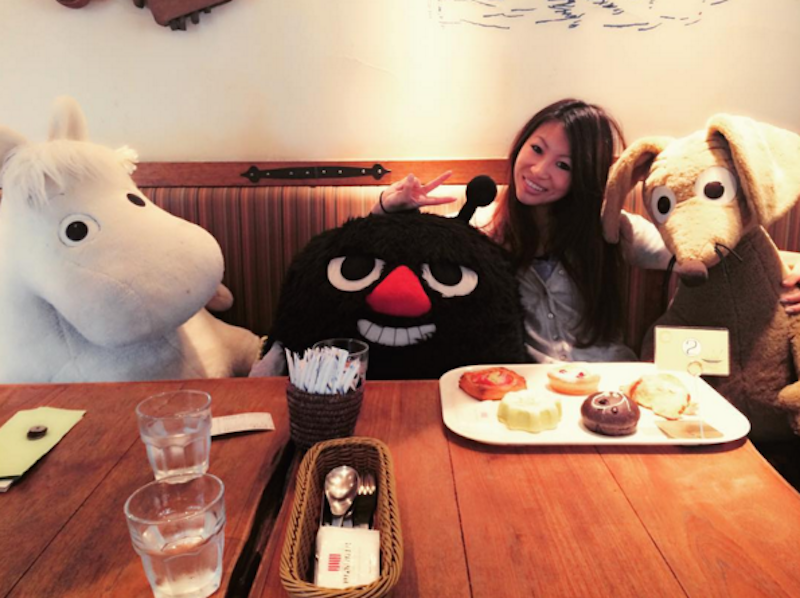

Finally inside the dazzling fluorescent Tokyo Dome City amusement park complex next to the baseball stadium, amongst the carousels and dancing fountains is my last stop: the beautiful Moomin Bakery & Café. Standing in line outside on a cold night I observe through the glass a man in a Moomin-suit and a chef dancing around. That’s all that can really be made out. Once inside the performance is over but happy Scandinavian folk music is playing, there’s a wooden cabin in one corner and an old fishing boat hanging from the ceiling, and sat amongst all the customers on chairs are giant plush toys of the characters: Moomintroll, Snork Maiden, Snufkin and so on. The menu includes flourishes like a Moomin-shaped side of rice with sliced olives for eyes.

Long before coming here I’d heard that its concept was of a place where a lonely person could come and have a meal with a Moomin. But it’s not like that. Nobody is on their own, except me. What is more I’m sitting at one of the only tables without a toy companion – in stilted Japanese I request a “Moomin”, by which I mean any sort of mythical Tove Jansson cartoon monster.

Across the room I watch a waitress conveying a massive rat-kangaroo-looking thing over to a little child sat at a table with his family and a Moomintroll. She waves its paw at the little child and he looks unimpressed and confused, and in that moment of confusion she confiscates his Moomintroll and brings it over to me. As she rotates the plump monster around the café she hold it very lovingly, pressing her cheek against the top of its head. She seats it opposite me. It’s firm to the touch and constantly attentive and gazes back at me with large blue Nordic eyes. I imagine this is probably what it feels like for a sugar daddy on a lunch date.

But anyway I thought it would be an interesting psychic experiment to have a coffee with a stuffed Moomintroll and so I look into its eyes for the duration of one sugary Scandinavian folk song, and it’s a blissful and dissociative encounter. Old episodes of the television show play on a projection screen above its head like a thought bubble, as though the troll is remembering and regaling me with stories about its day in the woods. Suddenly everything feels like a childhood fantasy coming true. The Moomin Bakery & Café, and all the other places I have visited, suggests that Western cafés have a long, long way to go if they want to. That they might become small spaces of fantasy, any fantasy, crammed in amongst the brimming cities. That they might become less like chains and more like immersive performance art projects.