“This is where all the scum gets washed up. The Port of Amsterdam. A dustbin for the Eurotrash.” (The Acid House)

Seen through the pungent fug drifting across our table, Amsterdam seems like the perfect place for a writer like Irvine Welsh to live. Europe’s bastion of liberal drug policy and – despite mounting pressure from EC fellows outside and conservative politicians within – still the city of choice for free thinkers with a taste for those generally forbidden pleasures, its subterranean population of itinerant bohemians, dancers, druggies and petty criminals infuses it with an edgy vitality. Perfect subject matter, right?

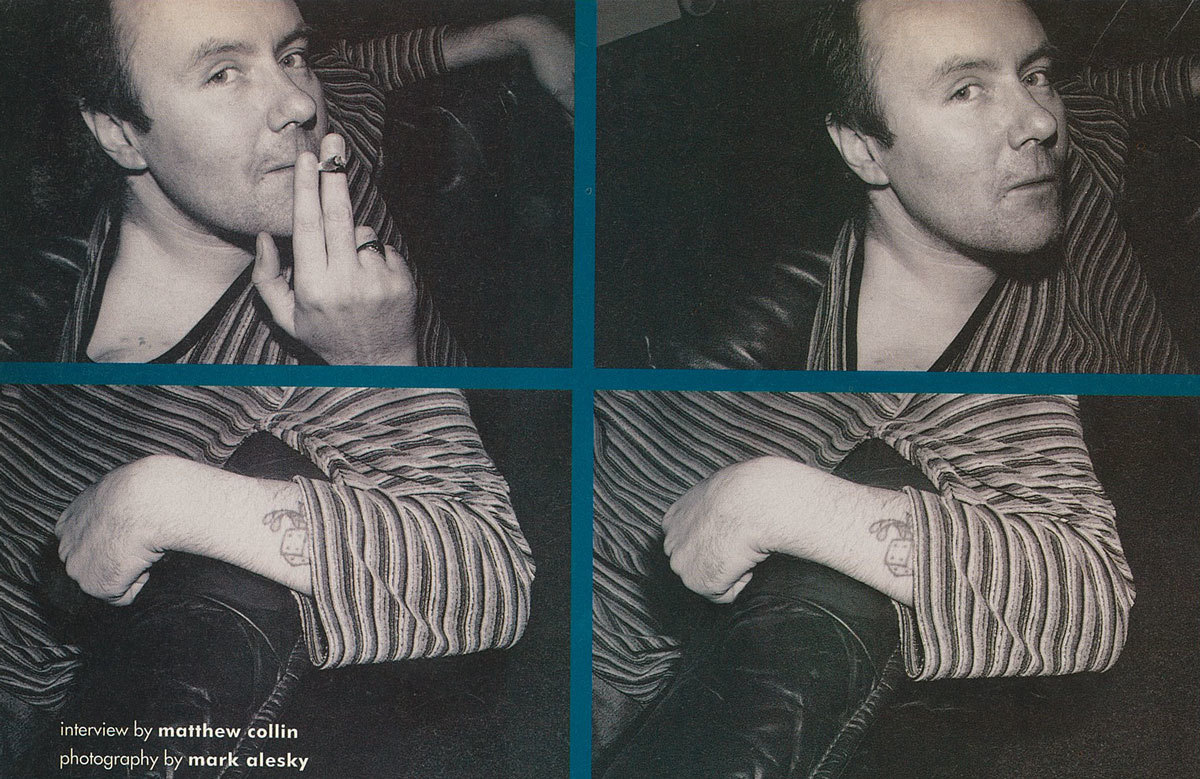

This big cuddly teddy bear called Irvine who’s sitting opposite me is our most vital of contemporary British authors. WHen he blazed out of nowhere in 1993, he became the first writer to take up the challenge of defining this chemical generation – not in a breathless, uncritical, celebratory way but with just the right blend of passionate acceptance and cynical refusal. Anyone who’s had any involvement in club culture post-1988 will get a shudder of recognition when. The blend of observation and imagination insists: this bloke knows the score, he knows who we are, and not only that, he’s trying to understand why we are who we are. The authenticity of the writing is beyond question: Irvine had danced and he’d locked into the bassline; he’d overdone it and got cabbaged too; he’d understood that the house scene, with its open-access non-elitism and entrepreneurial verve, had changed everything – or as he puts it, “one pill, and nothing was ever the same again”.

But to label him the ‘rave author’ is way too simplistic – it also suggests that he’s knocking out excepts from a clubber’s diary or sub-Richard Allen pulp rather than anything with greater depth. In fact, he places all his semi-autobiographical observations in the context of other, longer-established drug cultures, those of alcohol and opiates, and in their social context: these poor starved strangled ’90s. His aren’t downtrodden or miserable books, though (although they are sometimes grim: their first person narratives mean you get stuck in the heads of people you might might not want to be in a room with) – rather than attempting bleak, monochrome docu-drama, they shift reality one step beyond itself, twisting everyday situations off kilter with vicious surrealism, deadly humour, an insider’s ear for the subtlest nuances of dialect and slang and a virtuoso’s mastery of the art of the expected.

Irvine Welsh was born in 1958 in Leith, Edinburgh. He lived on the far from salubrious Muirhouse estate, left school at 16 and became an apprentice fixing TVs. He got pissed off with the job and went off down to London at the end of the ’70s, messing around in bedroom punk bands and moving from room to rented room. Later he returned to Edinburgh as a training officer with the council. In his time away, the chemistry of the city had altered: this proved to be a pivotal moment in the trajectory of his life. Like many other urban centres at the turn of the ’80s, Edinburgh was flooded with cheap Pakistani heroin: perfect for the new poor seeking oblivious release from economic alienations. “You had the onset of mass unemployment, all this despair and you had this massive influx of heroin. What happened was the drug of choice for many people changed from tobacco and alcohol to heroin. ” Ordinary people, he stresses. Smack had been democratised. “This whole mystique about the junkie you get from literature, the William Burroughs thing, is nonsense,” he says. “These punters weren’t like that, they were just punters that went for a pint a few years ago.”

Read: As the sequel lands in UK cinemas today, read our interview with the cast of Trainspotting.

With this new generation of addicts, Edinburgh’s schemes became notorious for their contractions of HIV infection. “The friends I had back up in Scotland, a lot of them were wiped out by HIV. Thinking of the people I’d grown up with and thinking ‘how the fuck could this happen?’, it made me quite angry and I tried to make sense of it by writing Trainspotting.” The characters in the series of interior monologues that became his first novel, Trainspotting, are vividly alive. Although you’d hardly call them sympathetic, the author never judges or condemns them. There’s Mark Renton, sick of smack and sick of himself. Begbie who lives for a ruck. Sick Boy who lives to fuck. They screw up, get screwed up, screw each other up… but there is joy in the book alongside the despair. As well as the catalysts of anger and disbelief at the decimation of these new opiate communities by AIDS, Irvine found himself energised by the more positive prompts of E culture as the ’80s drew to a close with a feeling of positivity he hadn’t experienced since the miner’s strike was crushed. “All of a sudden you had this re-energisation. Everything seemed to be possible again. It was partly to do with the drug, because it’s such a psychoactive thing; it was also that the repressed energies that a lot of people from punk had stamped out of them by the conformist yuppie ’80s were suddenly bang on again.”

A few fragments of the fledgling Trainspotting were published in Scottish literary magazine and anthologies. Other writers started contacting him, encouraging and demanding: who are you, where are you from, have you written any more of this stuff? “I was still a wee bit resistant to the whole thing – it’s a cultural thing, you think of writing as being some kind of effete, self-indulgent thing, not a real job. They kept on encouraging me to send bits out and the bits kept on getting published, so I sent the whole anuscript out and the first publisher I sent it to accepted it and published it. I thought, ‘I’ve published a book, maybe a few of my mates might buy it but it’ll basically just rot away on the shelves and nobody would hear about it.'”

This wasn’t going to be. On its publication in 1993, there were glowing reviews in the heavyweight press, calling the first-time author things like “the Scottish Céline of the ’90s” and “a major new talent” as they slummed in his opiated netherworld, examining him like an exotic insect under glass. Irvine glared back like a psycho from the book jacket, issuing bold ripostes, likening himself to a “cultural equivalent of the casuals” and admonishing: “I get kind of annoyed when people say, “Oh yes, here’s the ex-junkie voice of experience – now get back to oblivion.'” He refused to be patronised and pigeonholed, correctly insisting that drugs were no longer unique to the subcultural periphery, but an unremarkable part of everyday existence.

The following year came the collection of blackly comic sketches entitled The Acid House. Title: spot on. Mission: to boldly go. “I wanted to do something that wasn’t so much urban realism, something surreal and fantastic,” he says, “so I fired it out really quickly, over a period of four or five week.” The book saw him grappling with experiments in form, layout and language, its sharp narratives stressing his point that working class characters can have as rich and fantastic inner life as the Hampstead heroes of Eng Lit. “I was trying to subvert the traditions of Scottish working class fiction – I like the idea of talking squirrels, people turning into babies, flying saucers landing on a housing scheme. Claiming other genres like fantasy, romance and crime and putting them in that cultural setting as well, playing around a bit rather than writing Trainspotting 2, more social realism.”

For all his resistance to the literary life, after The Acid House, there was no doubt that he had finally become Irvine Welsh The Author. “The attention has been weird, it’s turned things a bit upside down. I’m just doing everything I was doing before – going out to clubs and getting off my tits and that, but now I go to pubs in Edinburgh and people come up to me and say ‘great book’ or ‘shite book’ or whatever, and everybody seems to have heard about it. It’s been strange becoming this big daft cult figure rather than just another arsewhole who’s E’d out of his face.”

Read: How Trainspotting schooled a lost generation of Scots in the power of patriotism.

Has it’s benefits though, right? “The great thing about fiction is that it retrospectively justifies everything you’ve done in your life, because nothing’s wasted. You look back on your life and think ‘God, I shouldn’t have taken all those drugs that time’ or ‘I shouldn’t have fallen out with those people’ or ‘I shouldn’t have stuck that shitey job for so long’ or ‘I shouldn’t have got involved in that disastrous relationship’ or ‘I shouldn’t have lived in that grot-hole of a place’, but it justifies everything because it’s all material that can be used in some shape or form. Even getting stuck with some boring bastard in the pub, you think ‘this is not a total waste of time’. Everything is salvageable. You can do something that really futile, like sit and watch Dutch soap operas all day long and think, ‘I’m just picking up some ideas for this next book.'”

In his new novel, Marabou Stork Nightmares, a football casual lies comatose in a hospital bed, fighting off the horrible memories of his violent, fucked-up life with reassuring fantasies of being a post-colonial explorer on the trail of an evil bird in a mythic South Africa. Yet as hospital staff impinge on his internal drama with enemas, tubes and injections and his family plague him with their home-made tapes of Shirley Bassey standards, the dream spins out of control; his unconsciousness starts playing tricks on him.

The tale is like feverish reverie – like those turbulent, sweated, half-waking nights after doing a dodgy pill – as he’s tugged in and out of consciousness. It’s dark phantasia recalls the perverted imaginings of Alasdair Gray’s cynical security man in 1982 Janine – the same blinding insight of the terminal fuck-up, his vision coming too late to save his soul. The book draws on submerged cultural memory – widespread Scottish dreams of emigration to more comfortable Commonwealth countries as the recession came down in the ’70s – and the hopelessness of growing up in those grim years when the quality of life deteriorated in direct correlation to the systematic humiliation of blue-collar industrial power. Even flight represents false hope, however; the book’s anti-hero observes wryly that the apartheid politics of Johannesburg are the politics of Edinburgh, the politics of any city in face, where the poor are boxed off in ghettos and even petty pleasures are policed as if they were suspect: “Back in Edinburgh, we would be Kaffirs; condemned to live out our lives in townships like Muirhouse or So-Wester-Hailes-To or Niddrie, self contained camps with fuck all in them, miles fae the toon. Brought in tae dae the crap jobs that nae other cunt wanted tae dae, then hassled by the polis if we hung around at night in groups.” Even the blazing vitality of even his most dislikable characters. It’s a thrilling ride.

Where next for the chronicler of acid dreams? Last year, Irvine relocated to Amsterdam, where he’s currently working on two screenplays of Channel 4 and planning an audio version of Trainspotting with music by Andy Weatherall. He’s not sure how long he will remain in the Dutch city. Maybe he’ll drift onwards when the buzz fades. Like his characters, you could imagine him in many places – Berlin, New York, London, San Francisco, maybe even Sydney – anywhere, in fact, that the music kicks and the mix is right.

Credits

Text Matthew Colin

Photography Mark Alesky