Most interviews with Tapz start by talking about immigrating. The 21-year-old rapper moved with his family from Zimbabwe to New Zealand when he was a kid. Growing up he learned to use music to situate himself in a place where he felt like an outsider.

As a writer, a repeated narrative is a red flag, something to avoid as much as possible to try and find something new. Preparing for our call I thought maybe we could talk about creativity, the local New Zealand hip hop scene, his continued ascent and growing global reputation. Recently signed to US-based G.O.O.D Management, Tapz is already blowing up spots on Zane Lowe’s Beats 1 show, clocking top spots on the US Spotify viral chart and sharing the stage with A$AP Ferg, G-Eazy and Danny Brown. Oh, and he hasn’t released an EP yet. This is all on the impossible strength of a handful of very, very good singles.

The only thing is, listening to his music ideas around relocation, isolation and movement to appear again and again. On his latest track, literally called Run Don’t Run, he calls back to his parent’s decision to leave their home, and how that choice continues to echo through all parts of his life.

When he raps, “Mamma said boy don’t you run/ Look how far we’ve come/ Don’t forget where you’re from/ I didn’t work work this hard/ Just to let them take it from you,” he evokes the tangle of emotions sitting in most young immigrant’s stomachs. This mix of guilt, expectation, opportunity and gratitude has increasingly been pointed to as the swell behind a new wave of Australian and Kiwi hip hop. What used to be the domain of white boys rapping about getting wasted is now dominated by young talents from all over the world, who left their homes as kids, and are now exploring what it means to create a new place to belong.

Speaking to Tapz on the phone, his New Zealand accent holding traces of a Zimbabwean past, cut with a blooming American twang, you realise how powerful this transition is. It’s not only making the scene better, music better, it’s creating a sensitive, intelligent dialog around immigration, home and community we should feel proud to be apart of. It’s a dialog with Tapz at its centre.

There’s been a lot of conversation about how Australian and New Zealand hip hop has really evolved in recent years, to reflect a more diverse community. Is that something in the air in the Auckland scene?

Yeah I see that in more diverse artists coming out, different cultures coming together and a more universal style is coming out of it. It’s a style that competes with the rest of the world on an international scale and that’s awesome to see. When I first moved to New Zealand it was kind of like no one was really accepting anyone.

I read when you arrived in New Zealand as a kid you realised everyone expected you to know how to rap.

When I went to high school everyone expected me to know how to rap because I was one of the only black guys and judging by the internet only black guys can rap. That was kind of how I started rapping and yeah it kind of worked out in the end.

Obviously music is a way to connect to people and fit in, but how did it feel to have such a cultural expectation thrust on you as a kid?

As a kid I always wanted to rap but I had doubts because I grew up watching Michael Jackson and I couldn’t understand what he was saying because I couldn’t speak English, but I understood the feeling. It wasn’t so much like, you’re black so you’re a rapper, but rather me embracing it, like actually I can do that.

So it was a tool to navigate this huge change you were going though.

Yeah in some ways. In my first couple of months I started hearing punk rock and I fell in love with the rebelliousness. I realised just the other day why that was, it’s because that’s how I was feeling: I felt aggression to the fact that people would treat me differently just because I was different. I was feeling rebellious because where I was from, the political structure had fallen. That was a way for me to come to terms with that and feel comfortable with the person I am.

Reading about you before we spoke I noticed people often bring this immigration narrative up. How much is it central to your work and how much is it just an easy talking point the media gravitates too?

I feel like it’s an important part of who I am, the music I make and who I want to be as an artist. It gave me a good perspective of different cultures. When I make music now I have that unique perspective, I can speak to more than just one audience. My goal is to be a global artist because I am a baby of the world you know? I want to keep moving because I love exercising different parts of my brain to communicate to all these different demographics.

Listening to Run Don’t Run I initially picked up these themes of displacement or disconnection, but chatting now it seems that’s not really what you’re feeling. If anything it’s the opposite, it’s about being connected to many places and people.

I think you’re right to an extent, but I view it in a different light. I thought how can I take this connection and reflect on how these people come to terms with disconnection. I’m grateful for the disconnection that happened to me, that’s the best thing that could happen, because disconnecting from everyone at that point in time meant that I could connect with myself.

It’s been really interesting to see artists digest the nuances and emotion of immigration in their music. Do you get a lot of people reaching out to you with their own experiences?

Yeah people can see that that move had an effect on me and that I care about people who are going through that. Although I know that it affects us all differently, and as a race as a people we honestly, we need each other. This sounds cliché and cheesy but we’re in this together.

We’ve talked a lot about movement, and soon you’ll make another move to the US. How do you feel about it?

I’m excited, I’m never attached to one place because I feel like I’m a baby of the world and of the universe, I care about people and wherever they are. That’s a testament to my parents moving me from Zimbabwe to New Zealand. I didn’t miss Zimbabwe and I won’t miss New Zealand even though I love those places with all of my heart. I’ll always hold a place for them. They have helped me in amazing ways.

You’re like a shark, you’ve got to keep moving.

Exactly, and I’m ok to keep moving. I’m not holding onto things that I’m not supposed to be holding onto.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret

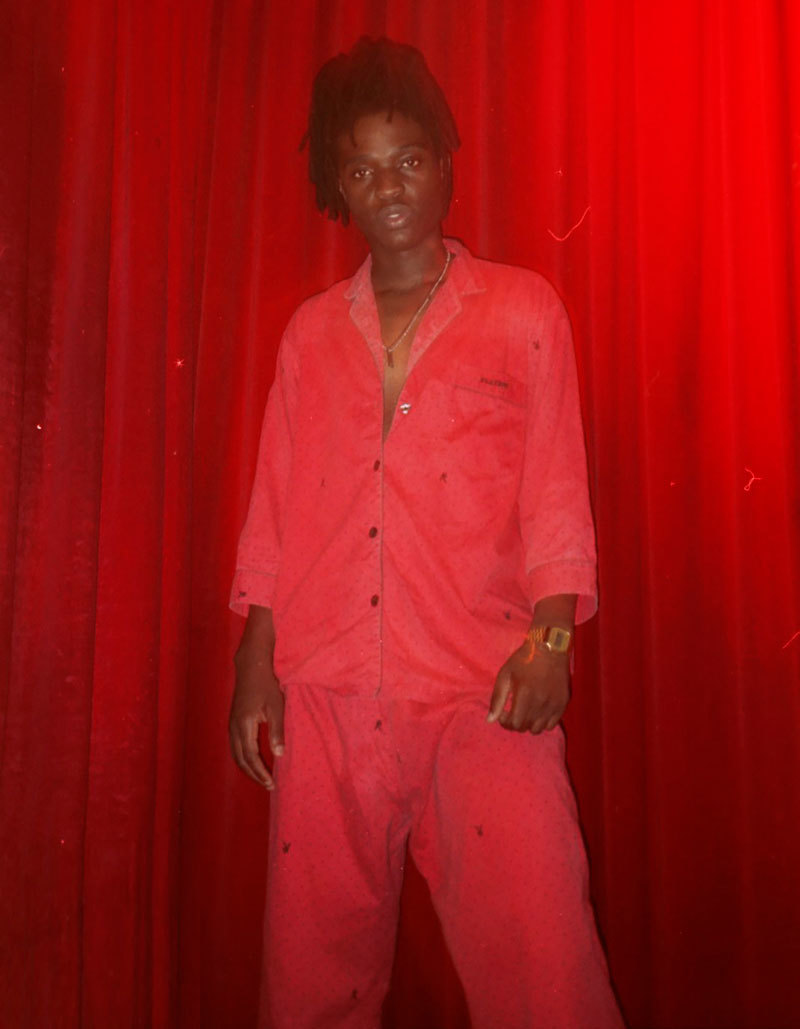

Photography Byron Spencer