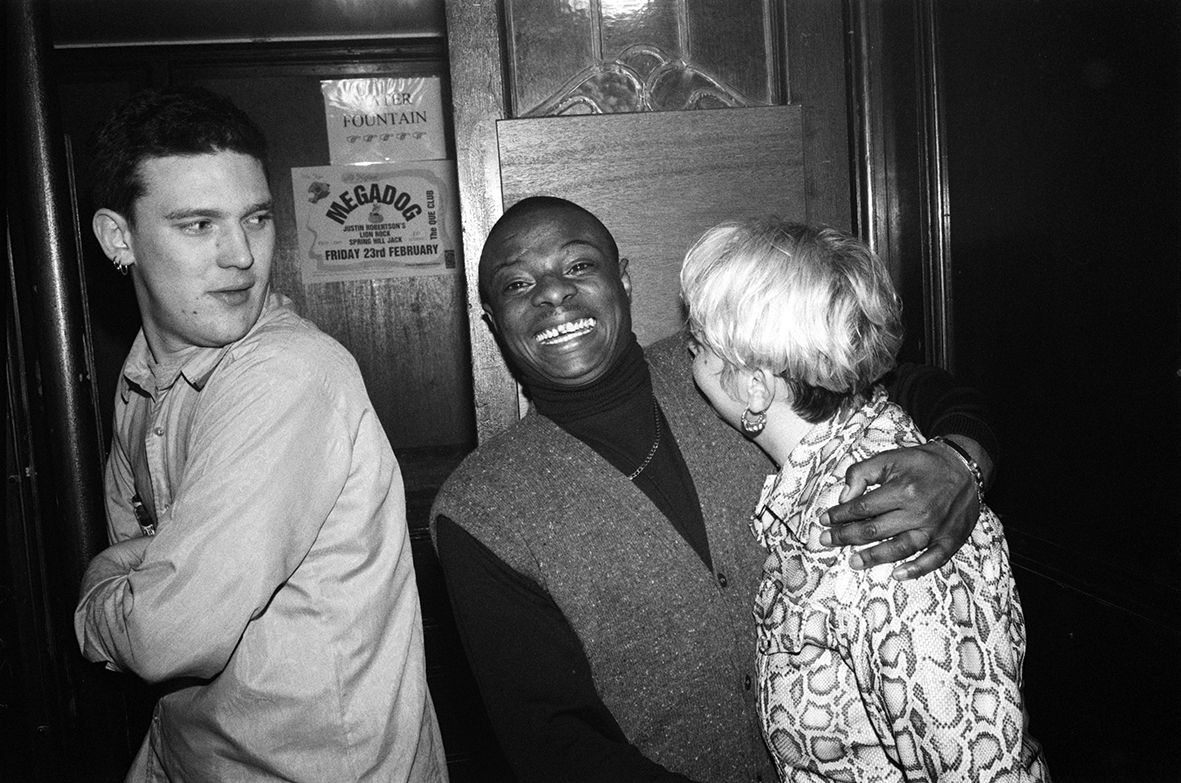

“Dad was wearing a camouflage jacket with black tracksuit bottoms while he was taking those shots. No question,” says Terry Donovan, recalling the night his father, the celebrated photographer Terence Donovan, accompanied him to The Que Club in Birmingham. “I would have been wearing jeans and a T-shirt that represented a techno club of the day.” A converted church hall, during the 1990s the space hosted the likes of David Bowie and Daft Punk; on the night Terence attended in 1996, the club night House of God was in full force. Now, as UK nightlife looks set to return, the largely unseen images are the subject of a new online show from London College of Fashion and the Terence Donovan Archive.

Better known for his contribution to Swinging London alongside his peers David Bailey and Brian Duffy — commonly referred to as “the Black Trinity” — Terence helped revolutionise magazine photography and later won acclaim for directing Robert Palmer’s iconic Addicted to Love video. Foregrounding 90s counterculture, his House of God series then is a stark contrast to the otherwise high fashion-led aesthetic of his work. As Alex Anthony, an archivist at The Terence Donovan Archive remarks, “Obviously a departure from [Terence]’s usual, more glamorous surroundings, the images he took in The Que Club are nonetheless just as fashion-orientated as any magazine editorial he shot. They are grainy and evocative, capturing the unpolished exuberance of the iconic club night.”

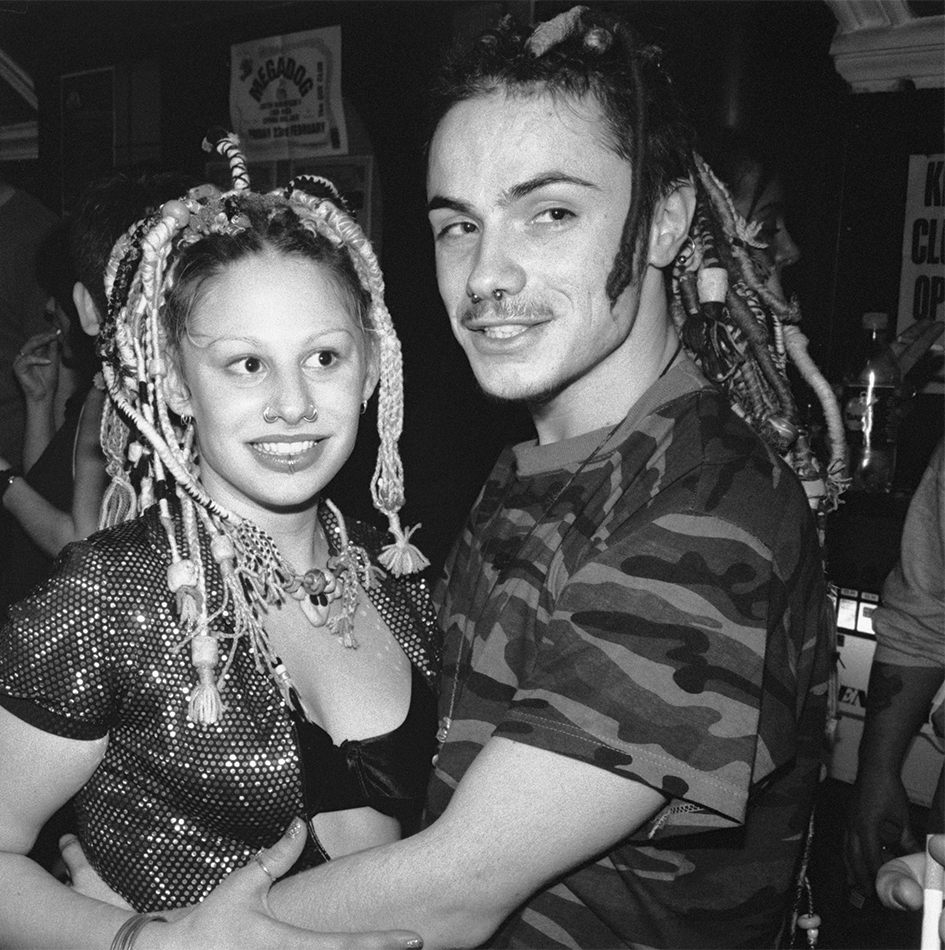

Started at Dance Factory in the basement of the Digbeth Institute (now O2 Institute Birmingham) in 1993, House of God was a long-running party with an agenda-less (and as a result, fully inclusive) point of view. Terry Donovan, who began DJing after his father took him to buy turntables from a mobile disco shop aged 15, began a resident slot, impressed by this energy on an early visit. “It was incredibly diverse,” he remembers, “with different music being played in all the rooms. In the early 90s, the house music crew ended up going to house music clubs, and the jungle crew ended up going to jungle raves… it kind of splintered looking back on it, but each group was quite happy. House of God had this way of spanning those divides and bringing people together.”

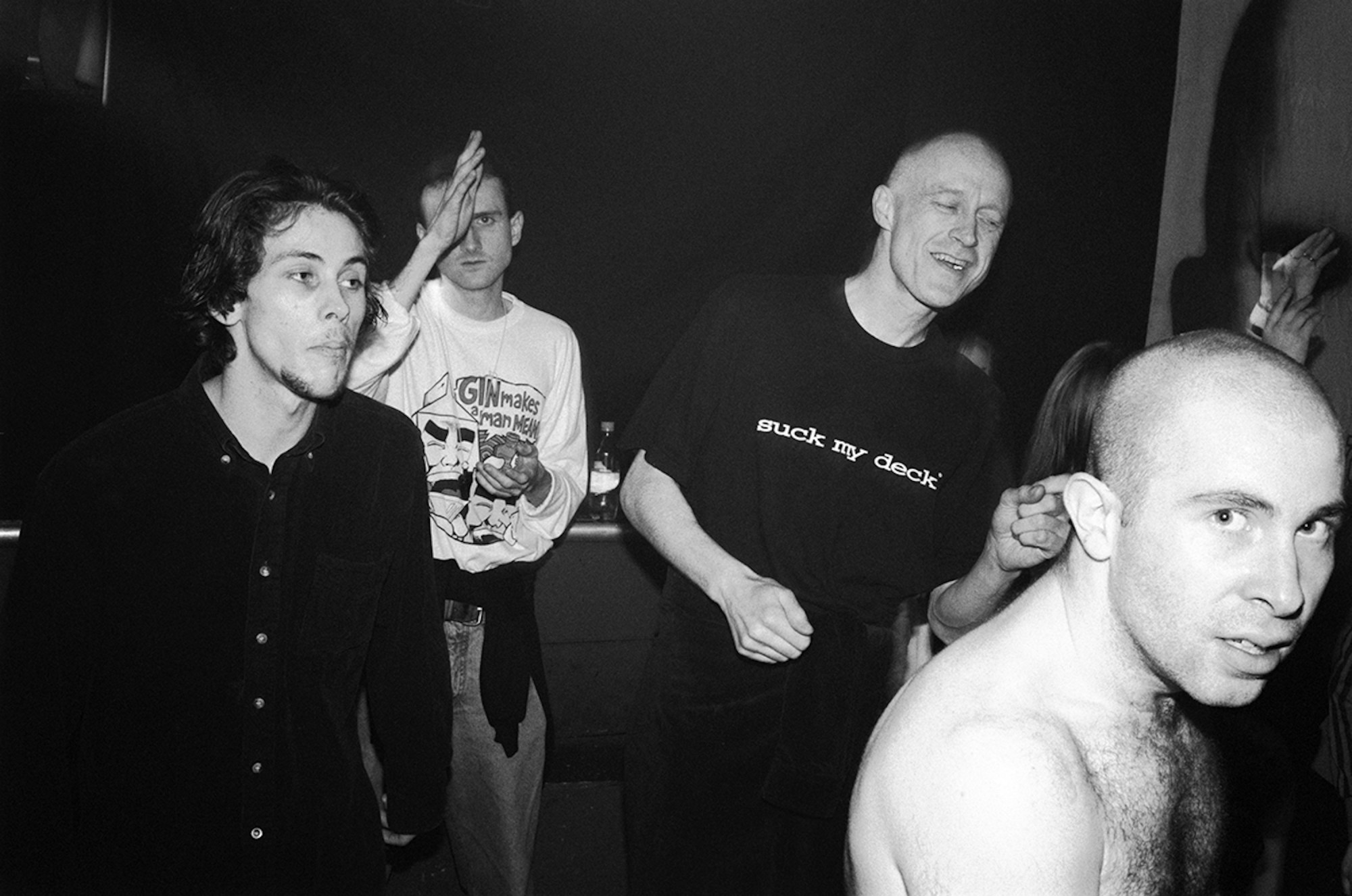

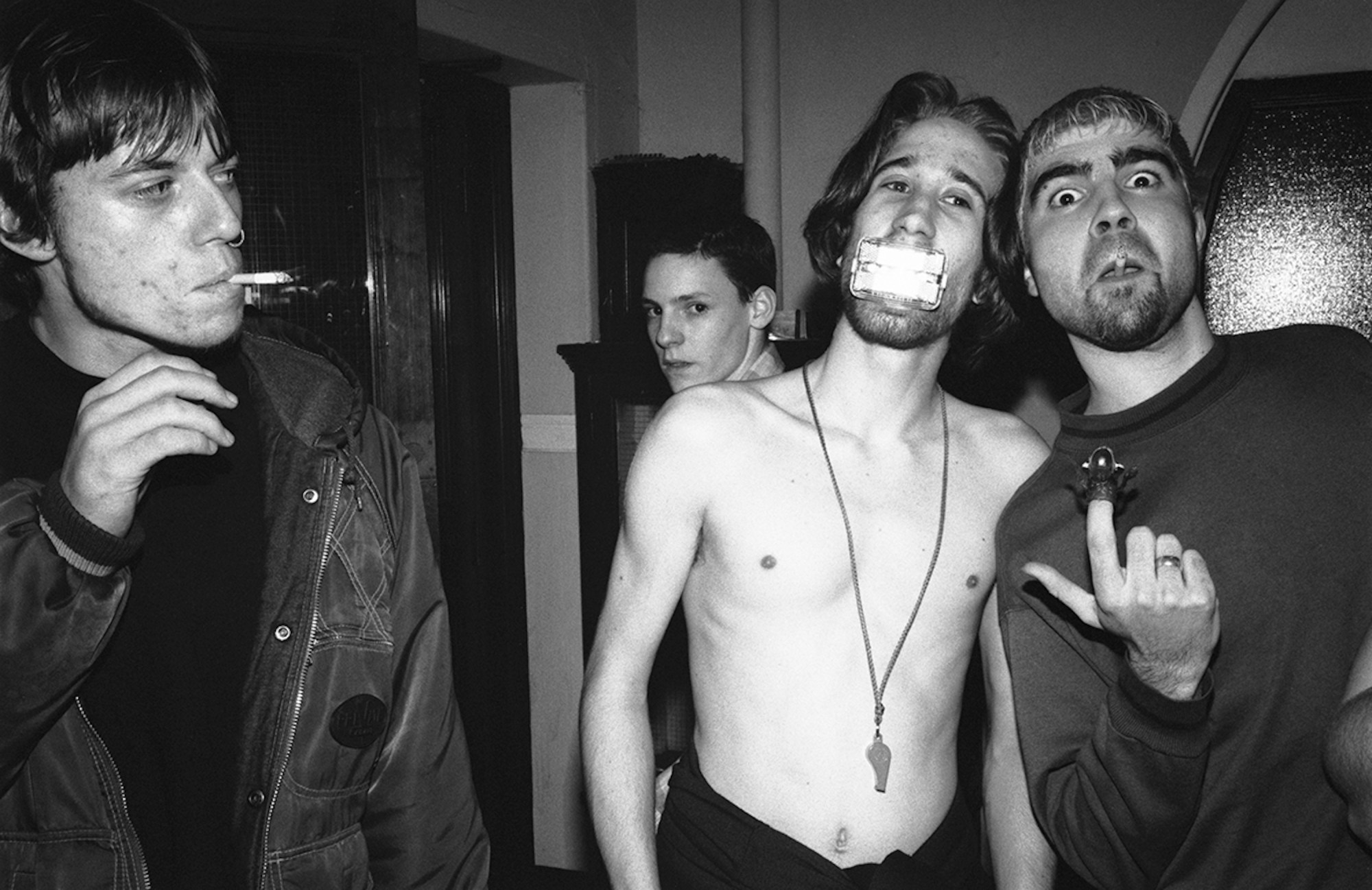

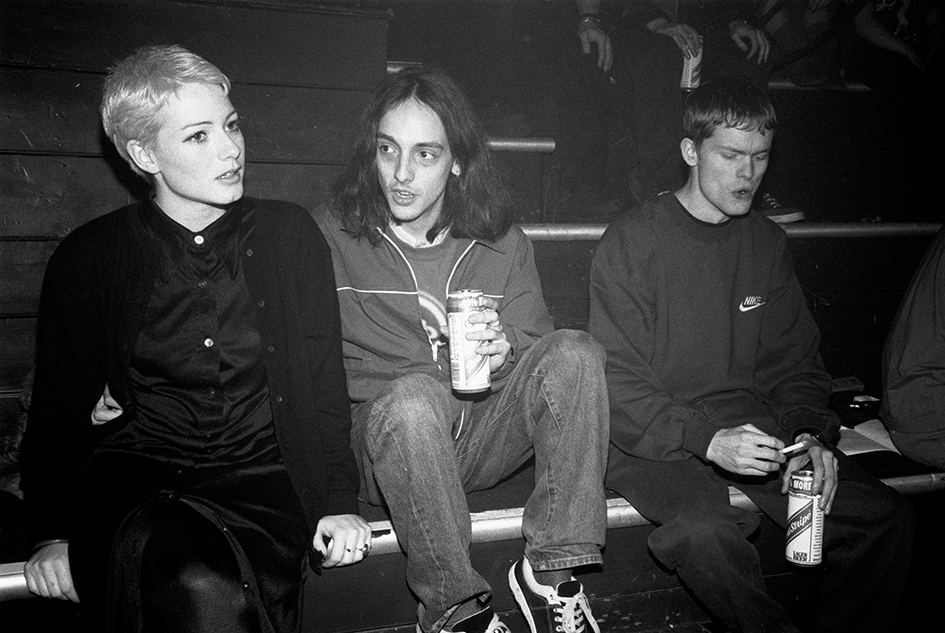

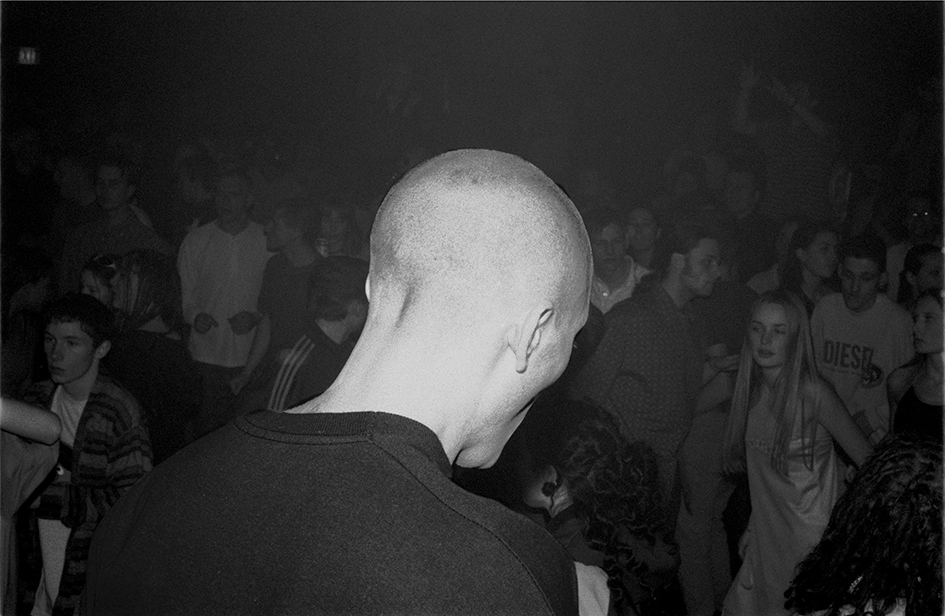

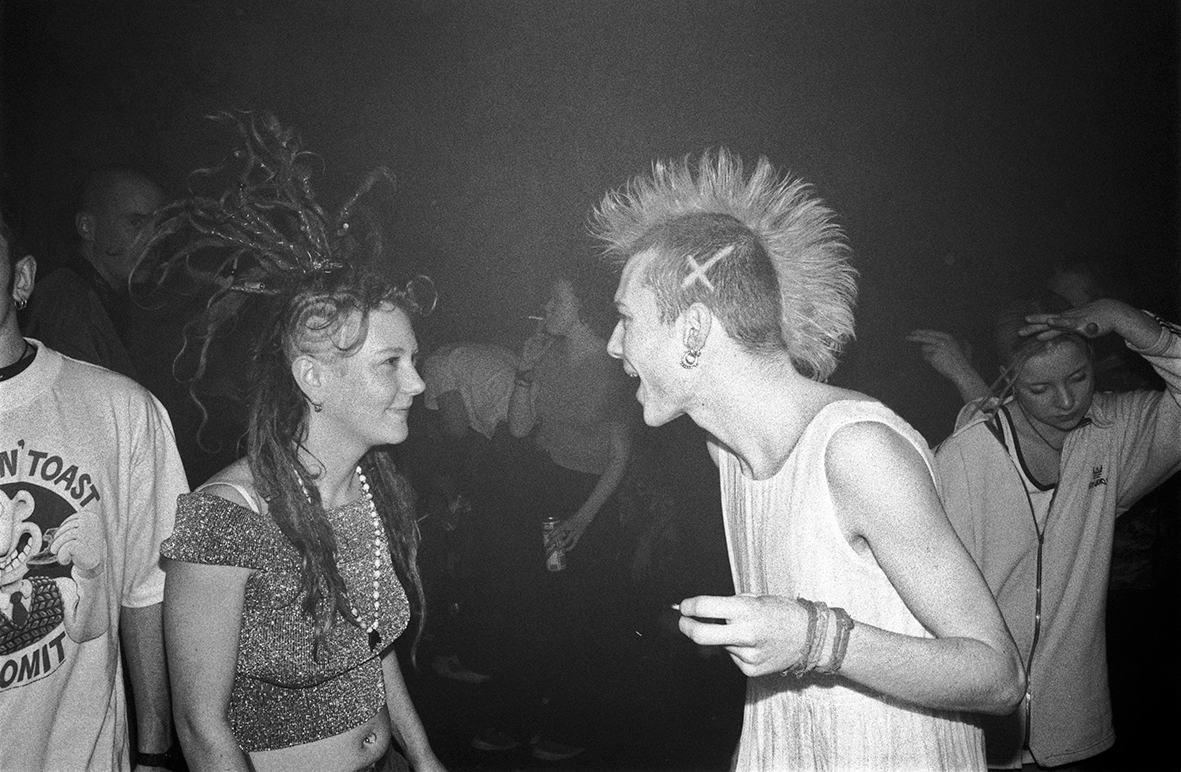

Terence too, he notes, had a particularly warm quality that found its way into his photography and at House of God, onto the dancefloor. “Dad’s clubbing days were long behind him by this point, but there was no environment he couldn’t feel comfortable in. He had this innate ability to engage with people and capture their image.” Using the same spirit with which he shot portraits of Jimi Hendrix, Marianne Faithfull and Princess Diana, here he turned his attention on partygoers in sportswear and glittering tees, with bare chests, punk mohawks and big smiles. His attending the club that night had been Terry’s idea, following House of God’s move to the new venue. “It was one of the first times I’d been involved in something where I had seen exponential growth, and it felt like ‘wow, you can do something cool, and it can grow without having to eat its young’. It was an incredible privilege to DJ there, and I just wanted to him to see that. He showed up with his camera and understood the energy, picking out some incredible characters.”

Shot in an era before camera phones and ahead of club photography’s omnipresence, Terence’s images not only document the fashion of the time but provide an engrossing record of nightlife pre-livestreams and social media. “You definitely get the sense in the images that Dad produced that people were largely unaware of his presence,” Terry says. “Even the people who were aware of him are clearly relaxed and unselfconscious. He had a staggering ability to go up to somebody and make them feel comfortable. His lens was very much in the middle of the crowd on the main dancefloor, and he managed to capture the individuality and intimacy of characters within all that intensity.”

Examining them today, in a moment when both Covid and Tory policy have left many of the UK’s nightclubs permanently shuttered, the images are a further example of something lost. “It seems an apt, if particularly poignant, time to bring fresh eyes and a new scrutiny to these pictures,” Anthony says, “looking at pictures of crowds mingling unselfconsciously and moving together en masse truly does feel like viewing a moment from the past.” The power of nostalgia, too, cannot be overlooked in an age when contemporary culture has a fierce interest in the 90s and early 00s, particularly within the clubbing arena. “I wonder if it has something to do with the house and techno scenes maturing and morphing at the time into the beginning of what they look like today,” Terry says. “The energy was fantastic, there were so many places where you could go and have what felt like life-changing experiences. I remember the whole period very fondly and in remarkable detail! I don’t think it’s unique to the 90s or 00s but the intensity of that period was special and worth revisiting over and over.”

See more images from ‘Terence Donovan in the Que Club’ here.

Credits

All images © Terence Donovan Archive