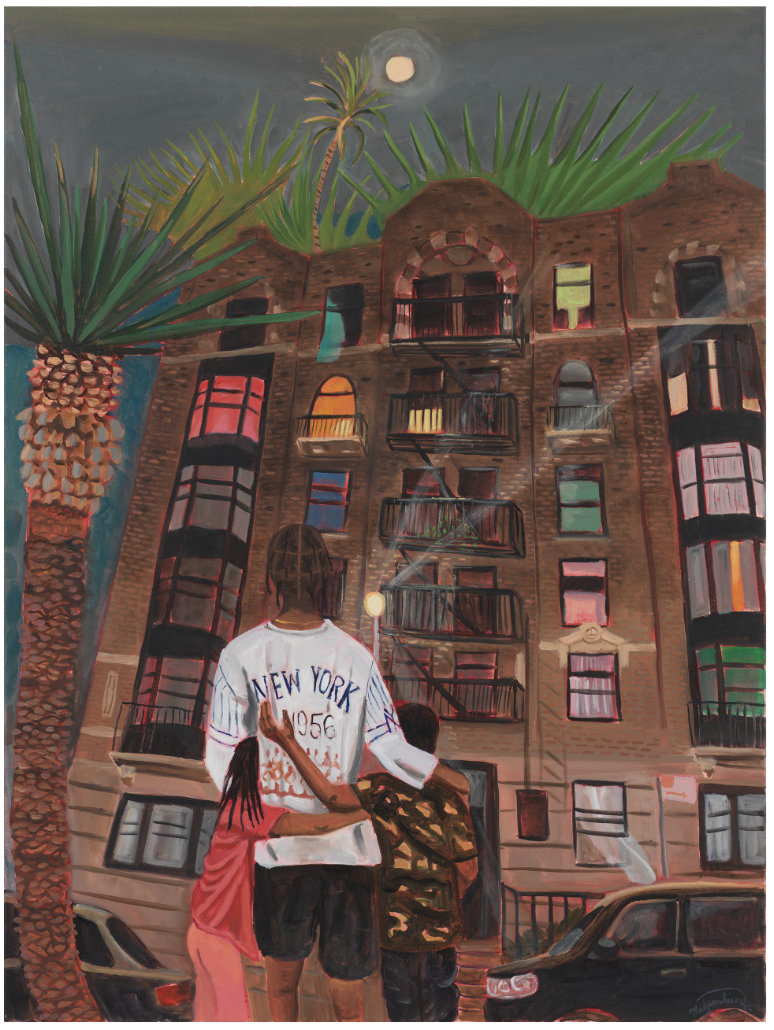

“This is Church avenue—once you get off the train here, you’re just in a whole other dimension,” says Madjeen Isaac, gesturing toward a painting depicting a street scene of Flatbush, Brooklyn. “You’ll hear all the Caribbean music, and the different dialects of English,” she continues, explaining the process behind this particular piece. ”So I cut out around it, and put Haiti in it.”

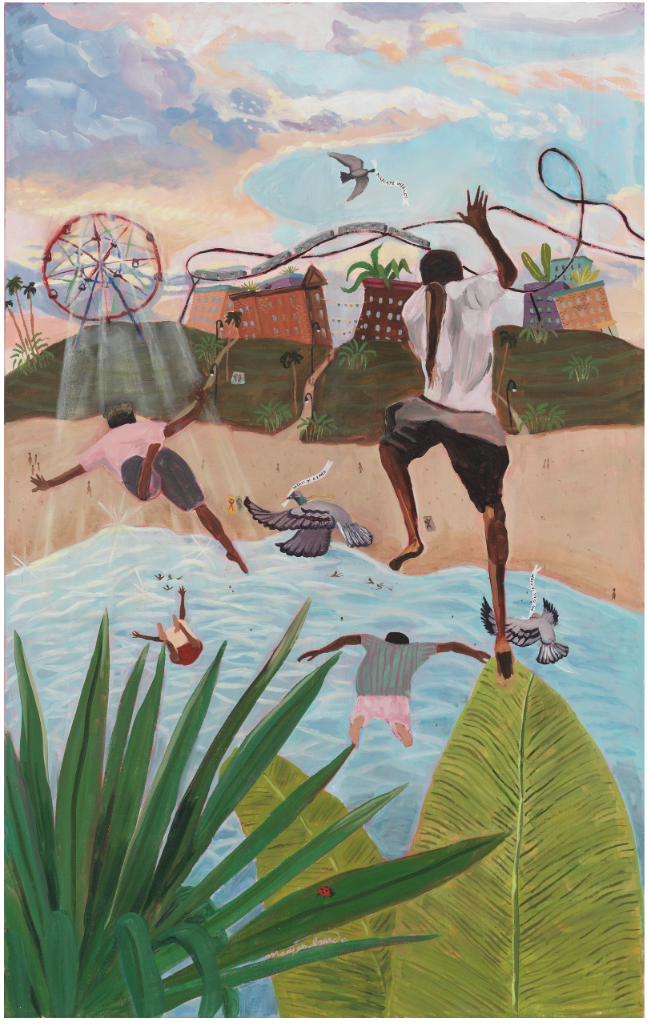

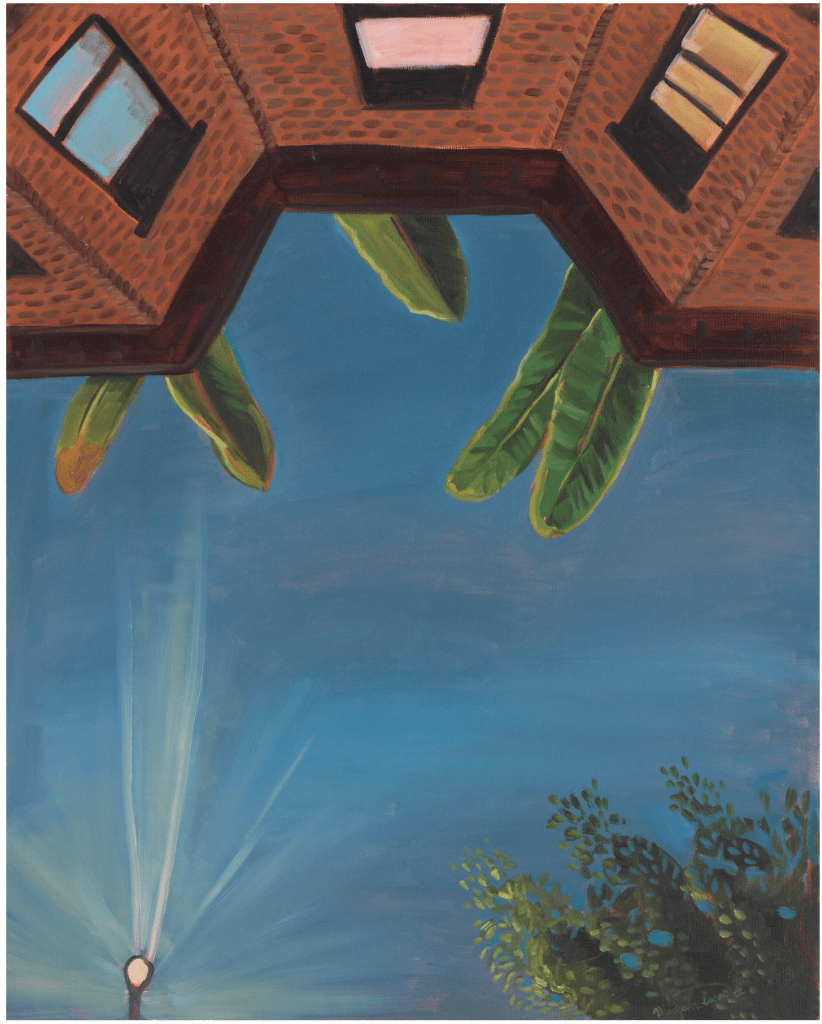

Flatbush is known for its vibrant Caribbean presence, shaped in large part by Haitian immigrants, including Madjeen’s family, who moved there before she was born. The enclave is also a bountiful source of inspiration for Madjeen’s practice, centered on joyful oil paintings that reimagine moments she observes in her community as a magically realistic hybrid world, blending her experience of Brooklyn with cherished memories of their ancestral homeland.

As she moves patiently through her studio while giving a brief tour, dozens of her vibrantly colored works in progress catch beams of light from the sun peeking subtly through a small window. Tender family photographs lie scattered on a workbench, across from a wall featuring mini-paintings on small squares of canvas. “They’re studies from my phone,” she says, explaining that many of her paintings begin as iPhone images. “When I want to take a break from my actual larger works, I just do these small studies. It’s just watching people, and looking at spaces in my community that I want to highlight.”

After she was given an assignment during undergrad to make a painting about culture, Madjeen continued on a journey to further investigate and uplift her own. She noticed how Haitians in her neighborhood carefully and intentionally brought pieces of their culture with them to New York, and set out to explore the idea of what it means to locate the feeling of home somewhere between two places. Influenced by artists like Kerry James Marshall, Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence, her work seeks to embody Haiti through details like mountain tops and banana trees that grow from the concrete in front of a bodega, for example. “When I think about all these buildings in my head,” she says, referring to the pre-war buildings that line the streets of Flatbush, “if I were to have an x-ray, I’d envision Caribbean households.”

As part of your training, you got a Master’s degree in art education and community practice. Can you tell me more about that?

I’m interested in expanding my practice into the community, and socially engaged work. I feel like it’s a never-ending journey.

A lot of my work is engaging and chatting with folks and finding ways to even have them be a part of the process. It’s super important for me. But during that program, it was just about learning the ethical ways of intervening into space, how to properly exit, getting trust.

But I really wanted to cultivate a better understanding of what it means for me to be an artist, not just a gallery artist, but an artist who was very involved in the community and gives back in that way. I view my works as blueprints for conversations about what it means to think about what we would like to see in our spaces and in our environments.

How does your interest in environmental justice intersects with your work?

I got interested in that, just remembering my trips to Haiti, when I would come from my uncle’s home. He lived on a farm. He would give the community produce, and I would volunteer at community gardens. It feels so second nature to me to be planting and tending to the garden.

I also collaborate with another small makeshift garden in my community, and we recently had a lot of folks come in and help out with that. And so just really like engaging in the practice of growing foods and learning and understanding that this was once our way of living, but we were stripped of it as time progressed. It’s, it’s just really mind-boggling to me a little bit.

I’m so sensitive to the change that I see in my community. So there’ll be a bunch of empty lots, but then they would then be, you know, taken up by development and it’s happening very fast. So thinking about ways in which we are either unfamiliar or we don’t know what our resources are. And so we don’t tap into these spaces fast enough to create the space we need.

I think it’s kind of wild to think that my, a lot of my family like came from that agricultural lifestyle, to then not have it anymore. What does it do to your body and your mind to not pass that down to future generations? It’s important for us to tap back into that, to know how to take care of ourselves, not depending on the system.

And it’s liberatory in that way, right? Like not being dependent on these systems that aren’t built to serve us.

I know that it’s impossible to completely live off of the land. We have shifting seasons and the world is like transforming like so much as we speak. But I think having that knowledge and even just being able to tap into it, take a break from working so much, can be very therapeutic. We just come back to our bodies and release, as a form of healing.

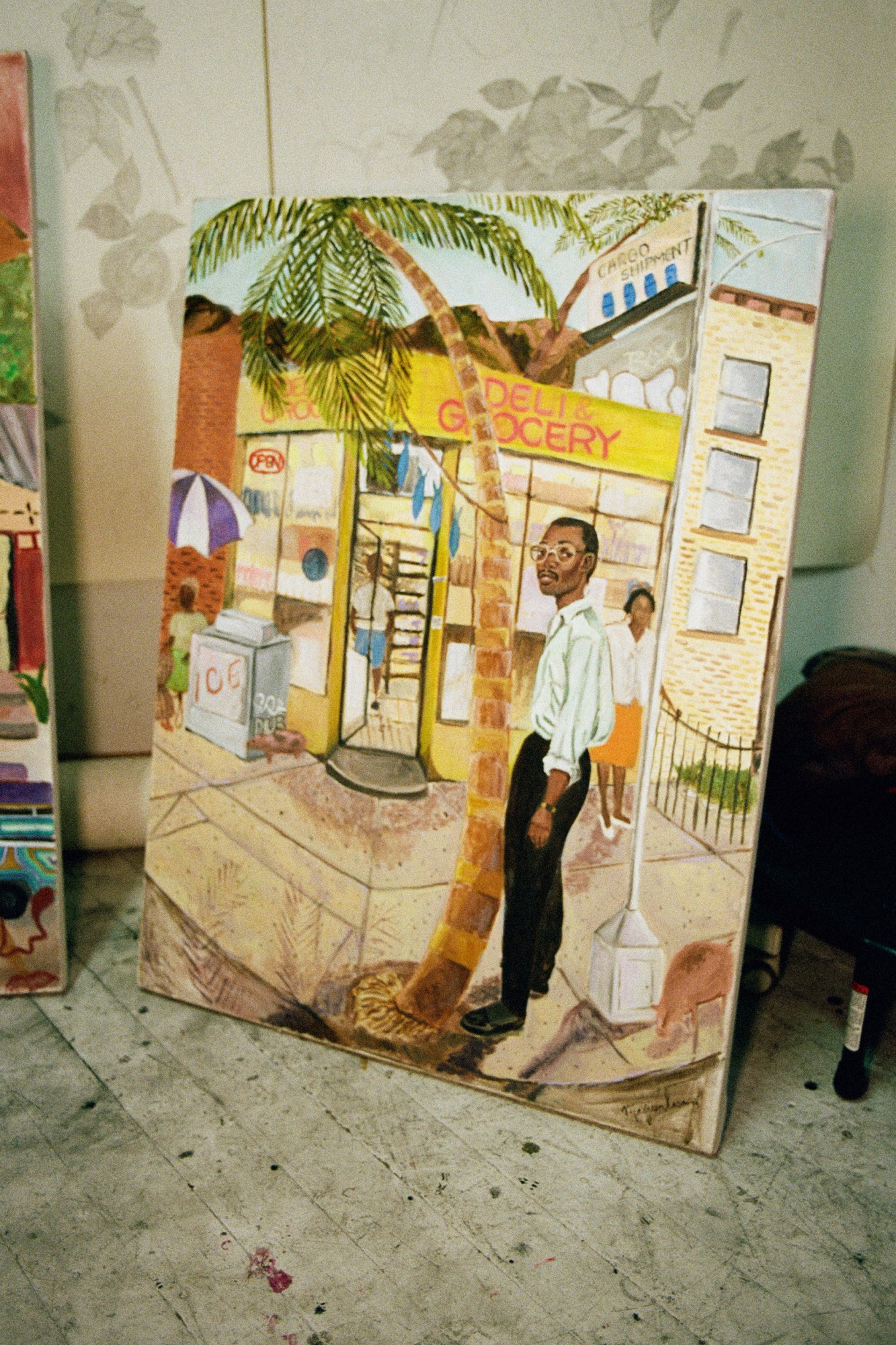

Can you tell me more about this painting of the man standing outside of a deli?

This is my dad. I try to capture his personality in this portrait and it’s him as his younger self before migrating to the states. He calls himself a fashionista, and he’s really into his jewelry and his clothes. And so I have him in his Sunday best. He loves playing the lotto. So I have him in front of a bodega. And he’s a great cook, so I have like the fish hanging on the clothing line. That’s something that I observed in Haiti. When you catch your fish, you hang it under the sun.

I always think about, what if he could do like life over? I think he would be like a really great chef or a great businessman. But you know, when you’re in immigrant spaces, you don’t really think about what you want to do. It’s about what you have to do.

How does your family feel about your career?

They get very excited seeing themselves in these works. Especially my dad, there was this one painting I did of him where folks are recognizing him like, oh my God, is that you?

He was like, “It’s me!”

I think it’s nice for them to see themselves in these worlds because it’s a sense of empowerment that they too can tap into leisure and rest and play. They won’t always understand every aspect of it, which is fine. I just have to keep doing what I have to do. It gives me a sense of sanity.

Which I’m sure is one of the things that they want for you, even if they don’t understand everything about your work.

Yeah it’s been a journey, but we’re making some strides.

Madjeen has partnered with Platform, the e-commerce site that helps viewers both discover and buy fine art, to showcase the four one-of-a-kind canvases featured in this story. All four works are available exclusively there.