For London-based designer Gui Rosa, lockdown struck at a rather inconvenient time. He’d just shown his graduate collection as part of the Central Saint Martins MA show during London Fashion Week, and was presenting his flamboyant crocheted pieces in the school’s annual exhibition when the klaxon was sounded. “We were basically escorted out of Saint Martins during the exhibition, which is when you try to get a job, speak to buyers and stuff like that,” he says. Since then, he’s been in his living room, now converted into “a makeshift atelier“, which he shares with fashion multi-hyphenate, and partner-in-crime, Harry Freegard.

Hearing how the pair spent the early days of their lockdown, in a terrace on Victoria Park, you’d be forgiven for mistaking their lives for an East London episode of Ab Fab. “At the start, we were surviving by partying at home every week,” says Harry. “For the sake of our mental health!” Gui hastily adds. “Otherwise, I wouldn’t know what’s a Friday and what’s a Monday!”

But as lockdown rolled from one week into another, they gradually settled into a new, more zen rhythm. “In a way, our practice kind of allows us to be very John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’. Harry’s basically appliqué-ing these old silk dresses, and most of my work is done by hand, it’s all hand-crochet,” says Gui. “We’ve just become, like, couch potatoes, but working ones.”

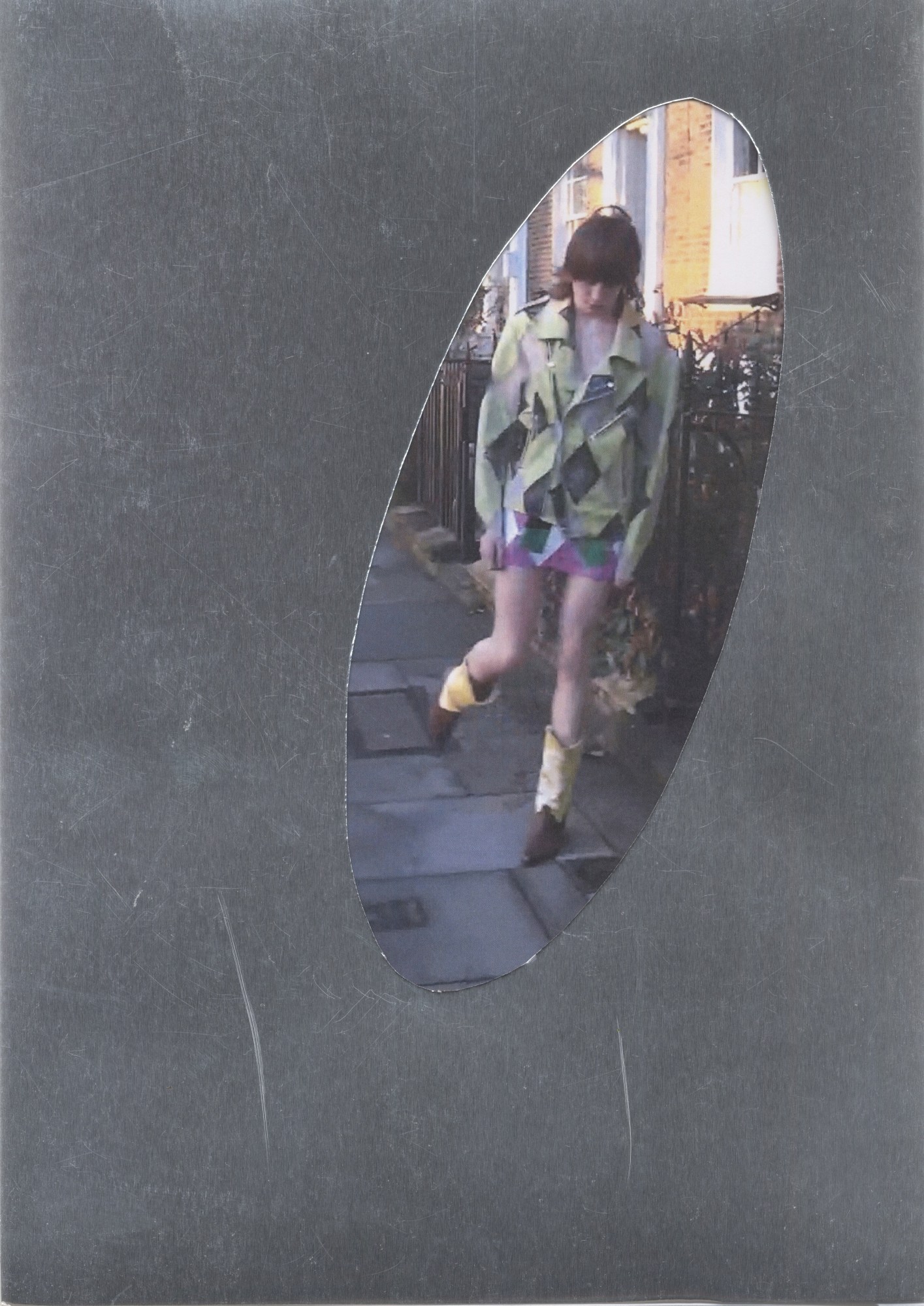

Looking back at Gui’s graduate collection, though, zen isn’t what first comes to mind. Inspired by the lot lizards of Middle America, the truck stop sex workers brought to mainstream attention by the 00s hoax autobiography of JT Leroy (later revealed to be the literary invention of writer Laura Albert) it was a loud, proud confluence of colours and social codes. There was an argyle check biker jacket, for example, its component diamonds cut from acid-green ostrich leather and black lace, communicating luxury and gaudiness, daintiness and grit. And then there was a cropped denim jacket and belted skirt combo, with concertina ruffles of hand-crocheted lemon sherbet mohair.

“Basically, it started with a hypothetical cross-country trip from Baltimore to San Francisco, very John Waters’ Carsick vibes,” explains Gui, who almost received a scholarship to take the trip IRL until “the patrons were like ‘Oh no, you can’t do that. Can you picture yourself in the middle of America? You’d probably die!’”

In lieu of witnessing West Virginia’s late-night lay-by culture first hand, he set out to infuse the hypermasculinity of the stereotypical trucker ‘John’ with the candy-sweet girliness associated with those plying their trade. “It was about combining this very masculine, macho attitude, represented through sturdy outerwear pieces like denim jackets and cowboy boots, with more feminine elements, like domestic lacemaking and crocheting,” says Gui.

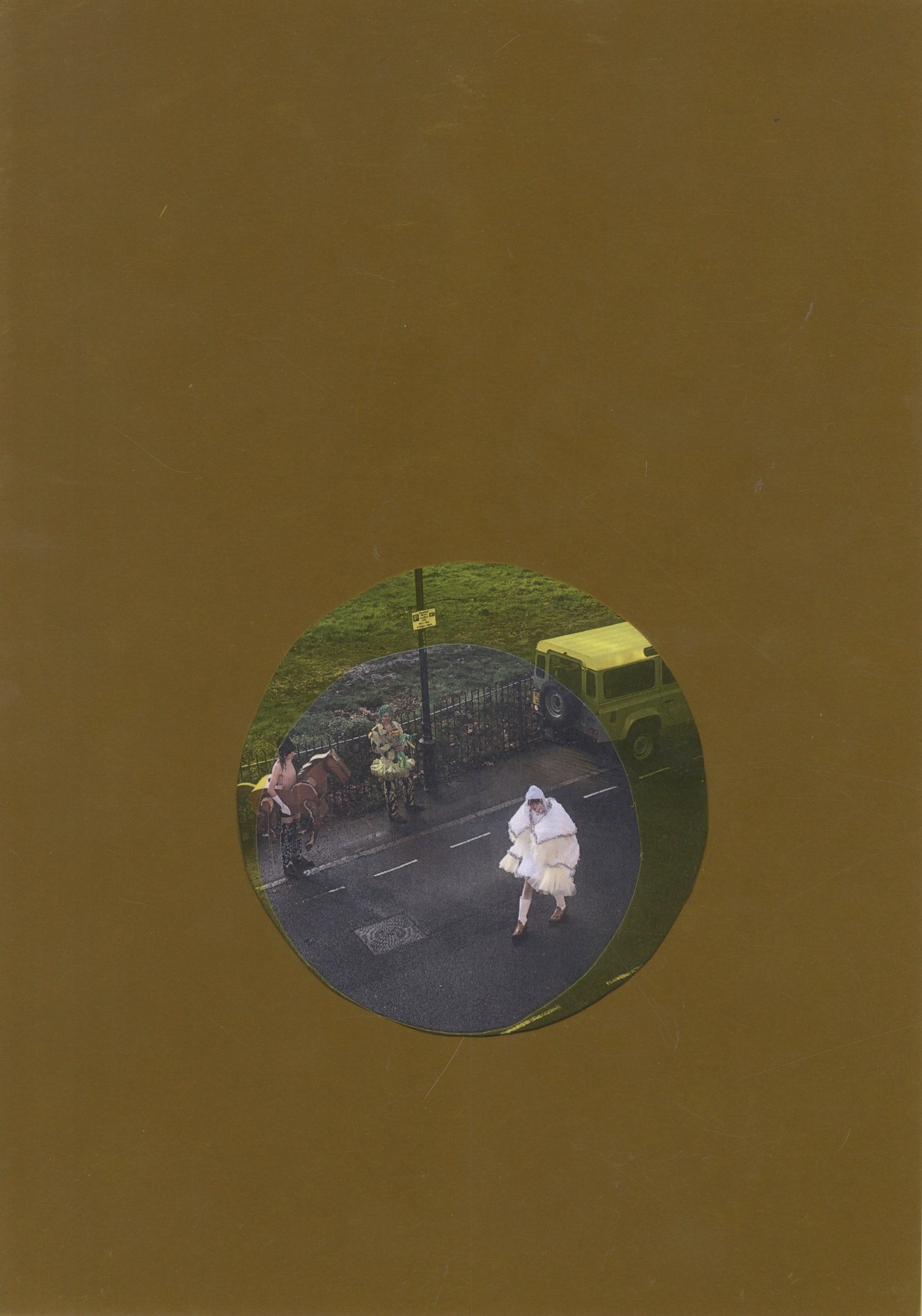

For the collection’s accompanying shoot, filmed by Harry on a 00s handycam, they had the boys who walked the show crawl the curbs around Victoria Park, as if waiting to be picked up by passers-by. “Gui’s collection was obviously inspired by the lot lizards, and the whole JT Leroy moment, which is something that I’ve always been inspired by as well,” says Harry. “I was gifted a raccoon penis bone necklace [an amulet worn by adherents to lot lizard culture] and I’ve emailed with Laura Albert loads. She’s insane!”

“I wanted it to be a bit voyeuristic, a bit austere, and a bit weird,” he continues. “In JT Leroy’s stories, there’s always a certain vulnerability, so we needed to have the natural vulnerability of these boys in the freezing cold, hanging around these cars — because that’s the reality of the lot lizard, they don’t really want to be there.”

Though the images may have been shot before lockdown, their lo-fi local flair has acquired new relevance in the pandemic-precipitated era of bedroom Zoom shoots. While neither Gui nor Harry anticipated the way the world was heading, it nonetheless reads as oddly prescient against the industry-wide calls for decluttering and slowing down. “We just wanted it to look a bit more stripped back, without a set and hair and make-up, because fashion’s moving so bloody quickly,” says Harry. “Why not just do it at our house with people we know? We like working small, and I think the industry’s now moving in that direction.”

Though fashion may need to compromise on the scale at which it operates, that doesn’t need to come with a correlating sacrifice in creativity. If anything, redirecting efforts away from profit-driven targets could allow us to reconnect with one of fashion’s essential functions — as a conduit for imagination and fantasy.

“Fashion keeps us sane, it gives us something to do, and it gives us a goal, even if it is just to look stunning for the day. Or not even stunning,” says Harry. “Maybe you want to look like a Lana del Rey strung-out wreck, but you can achieve that just by smearing your mascara. Those little details remind us that, even though we’ve been stuck in this house for many months, there’s still an outside world, and there are still things to achieve.”

Credits

Photography Harry Freegard