It helps to have a local hero. I was lucky enough to have David Hockney as mine. So with yesterday’s news that next year the Tate Britain is organizing the biggest retrospective of his work since his 1988 LACMA retrospective (he’ll also be turning 80) it’s as good a time as any to gush relentlessly about the brilliant, bright path he lit for me growing up gay and city-dysmorphic in Bradford.

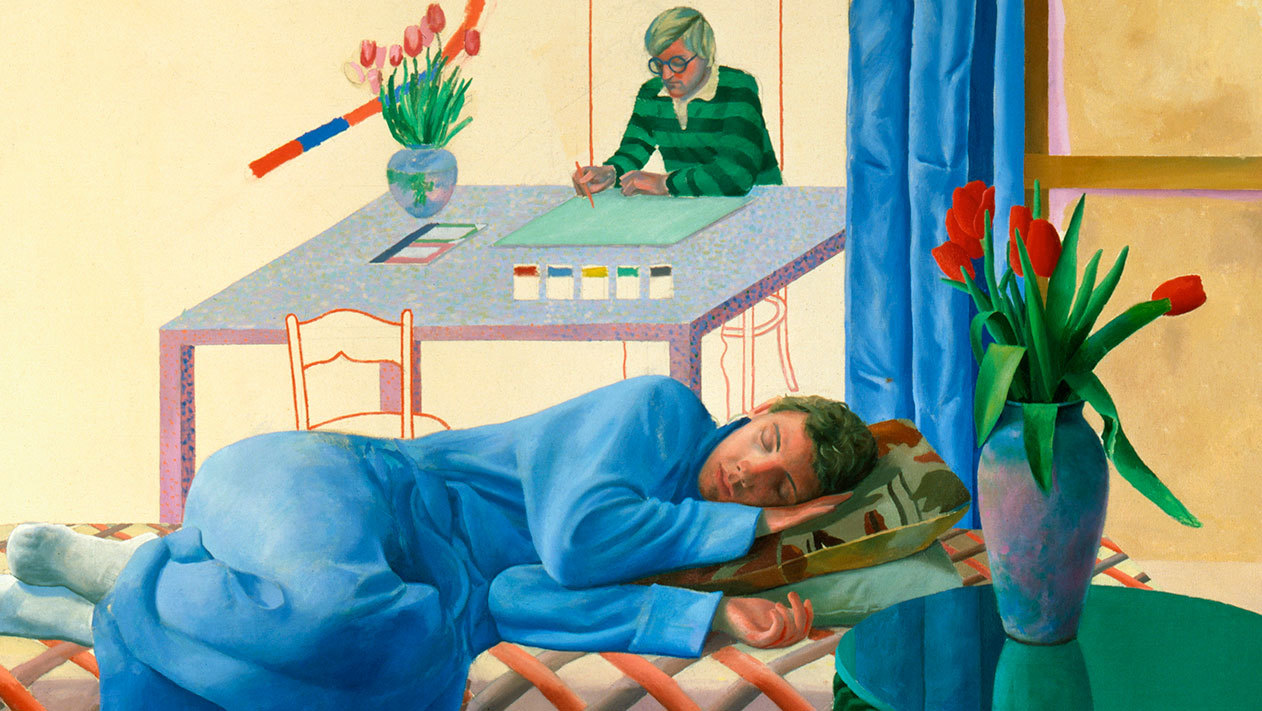

Not that mutual gayness or the desire to live elsewhere were the first things that drew me to Hockney — they came later. Instead, it was all that color. The joy and optimism of his turquoise pools, the vivid vases and flowers, and the technicolor canyons all offering a counterpoint to some of the more somber palettes of Yorkshire life: my brown school blazer, the blackened sandstone, and the deep amber of real ale. Quite often in life, an aesthetic attraction can lead you down an ever-more profound path — certainly the case with me and Hockney.

At primary school in the 80s, we regularly went to visit the local Salts Mill, a space full of his works (there thanks to the enriching friendship between the artist and the young entrepreneur-owner Jonathan Silver, who’d taken over the gigantic, run-down mill in the Saltaire village on Bradford’s outskirts and turned it into a center of art, design and culture). When we went down with our pads and pencils, I joyously copied his colorful strokes. Little did I know that he’d be influencing my life in many other ways for the next few decades.

Hockney was always in the air growing up in Bradford. He attended the same school as me (he once faxed an entire artwork for students to receive and re-assemble), practically every local household had one of his posters on their wall and his drawings of his dog “Little Boodgie” adorned the cups, saucers and aprons at the American-style diner. If I’d been a few years older, I might even have spent a week painting with him in Malibu, like the lucky-buggers from sixth-form who were taken there by our art teacher — and Hockney’s friend — Robert Walker. Bitterness about missing that trip aside, the importance of all of this local Hockney-mania was that there was an ongoing civic celebration of a confident, stylish, gifted, and openly gay man when I needed it most. This was the 80s after all, with Bradford falling to bits and Thatcher banning the “promotion of homosexuality” in schools through Section 28. Homophobia was rampant (more in the media than through gay bullying, for me), I’d never met a single gay person and was firmly in the closet, but at least there was Hockney and the world he opened up to me.

It felt unbelievably reassuring to have him as a local trailblazer. Later, as a teenager, when shows like Queer As Folk were raising awareness of mainstream gay culture, I didn’t need them, because I already had my future mapped out by Hockney knocking round Notting Hill, Hockney caught in Warhol’s pink screenprint, and — best of all — Hockney & co. chilling poolside in California. In the 60s, when homosexuality was still illegal in the UK, Hockney had escaped to LA, where he was painting beautiful naked men, lounging by pools. Peter Getting out of Nick’s Pool, Man in Shower in Beverley Hills, and Sunbather showed tanned, tantalizing gay love playing out under blue skies and glowing sunshine. It was unapologetic and radical, but in the lowest-key, most leisurely of ways. I’m sure his paintings shocked some at the time, but their natural, wholesome, joyous quality was the perfect argument against those who thought gay love was disgusting or wrong. In 1967, the year homosexuality was legalized in the UK, Hockney debuted his most iconic painting, A Bigger Splash. What better way to celebrate than by diving naked into a Cali pool?

His art gave me great optimism that life beyond the closet was going to be bright, beautiful and colorful. I had a highly visible example of someone who’d gone to the same school and moved on to an artistic, stylish and global-trotting life. He set up studios in London, Paris, and LA, spent summers on Fire Island, and took trips to New York, Marrakech, the South of France, the Grand Canyon, Hawaii, Japan, and China. He showed everyone that serious artists could also be rampantly and brilliantly sociable, as he mixed with people from fashion, literature, dance, film, and art; Ossie Clark, Celia Birtwell, Wayne Sleep, Lucien Freud, Robert Mapplethorpe, Christopher Isherwood, and Divine were all regular fixtures in his life and often his portraits, too. In one old photo, where he’s seen greeting Andy Warhol, Hockney out-dazzles Pop Art and New York’s finest and wins the battle of the speccy, bottle blonds. Just like his work, his style was an outward example of his confidence. Peroxide hair, big glasses, bold stripes, caps, ties and braces were his bold signatures.

For someone dreaming of the same adventures, it felt good to have a gay man who’d already trodden me a path. But what also chimed with me is that he’s never wanted to turn his back on where he came from. His Bradford accent has never picked up a Transatlantic twang, he’s painted Yorkshire’s landscapes as much as LA’s hills and has kept up a cultural link with his birth city through collections at Salts Mill and Cartwright Hall. In the 90s, he created a live global event, faxing a 144-sheet composite image, Tennis, from Malibu to Saltaire’s 1853 Gallery. He went on to do bright, semi-abstracted landscapes of the Aire Valley and studies of the Yorkshire Wolds. The only thing that has almost made him cut his ties with Bradford was the suggestion a couple of years back that the Council should sell their Hockney collection to raise much-needed funds. The city would have been mad to flog its most famous son’s works. As one councillor brilliantly stated, “You can only sell the family silver once.”

Through his work, Hockney has also provided me with a template of someone always staying modern and trying new things, never getting stuck in their ways. The range of his techniques is breathtaking, including etchings, drawings, lithographs and photo montages, and his use of materials ranges from acrylics and oils to photocopiers and iPads. I’ve been following his art and his antics for nearly three decades now, and whenever I think I’ve seen it all, another work – or even a whole movement – will crop up: his French Vogue covers, his Olympic poster, his book on the Old Masters or his opera sets for the Glyndebourne festival, London’s Royal Opera House and New York’s Met.

He’s showed me that you can be British, but not a Brit abroad, that a Yorkshireman can be a cultivated, cosmopolitan world citizen, that being gay is great, that art can be immediate and enjoyable, but also intellectual and existential. Growing up gay in Bradford may have had its downsides, but at least I was always able to turn to the subtle, world-turning talent and solar confidence of Hockney and the joy, light and optimism of his works.

Credits

Text Stuart Brumfitt

Main image Model with Unfinished Self-Portrait, 1977 © David Hockney