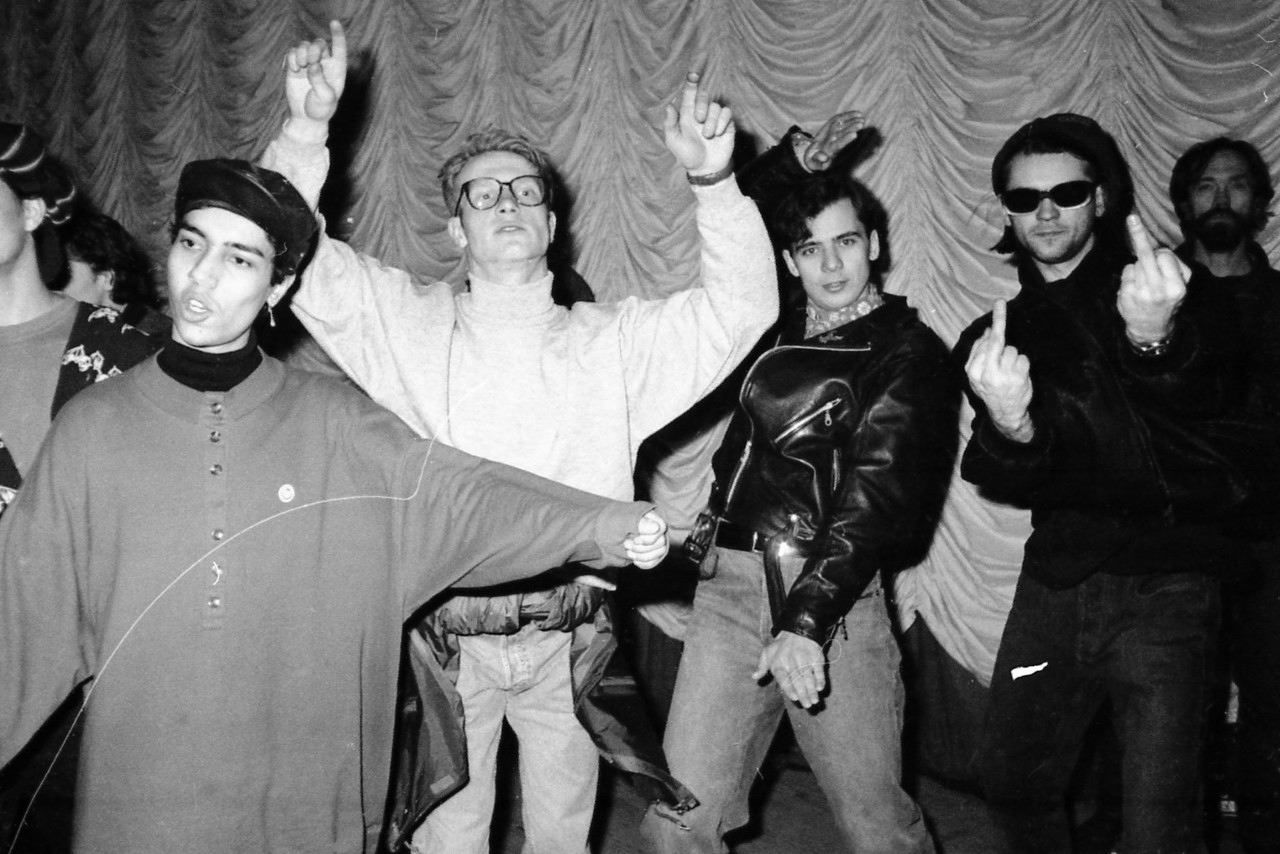

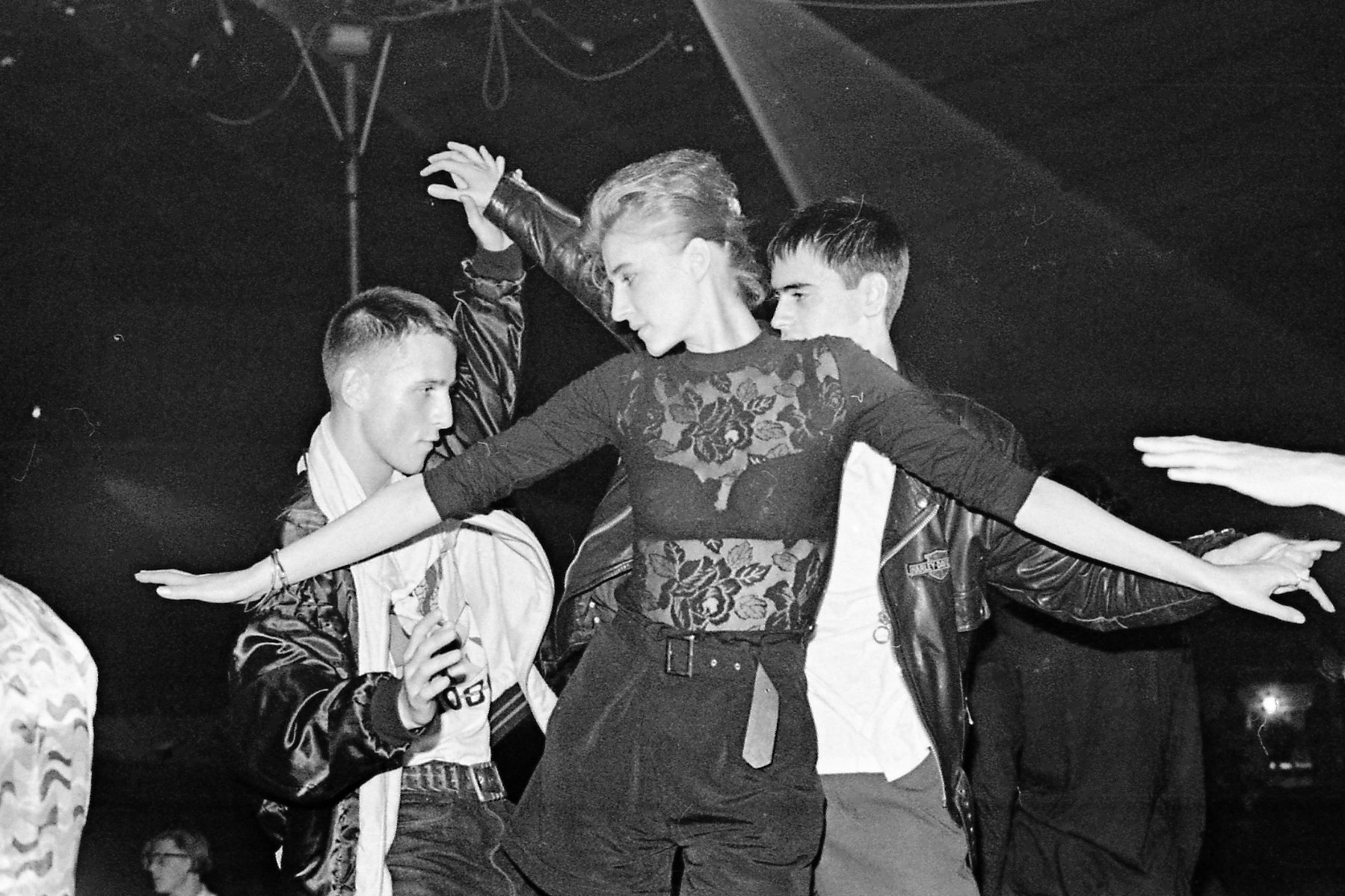

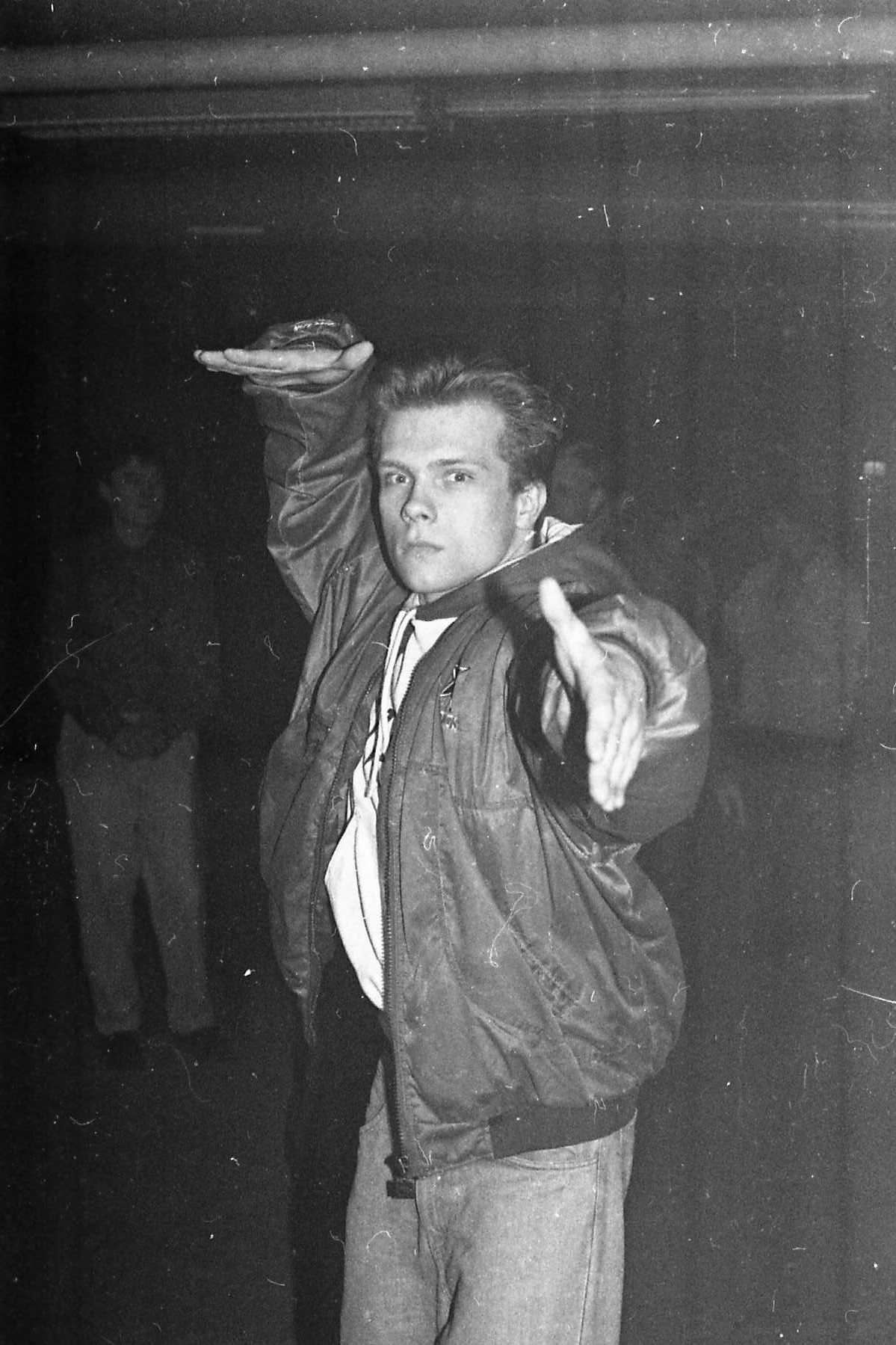

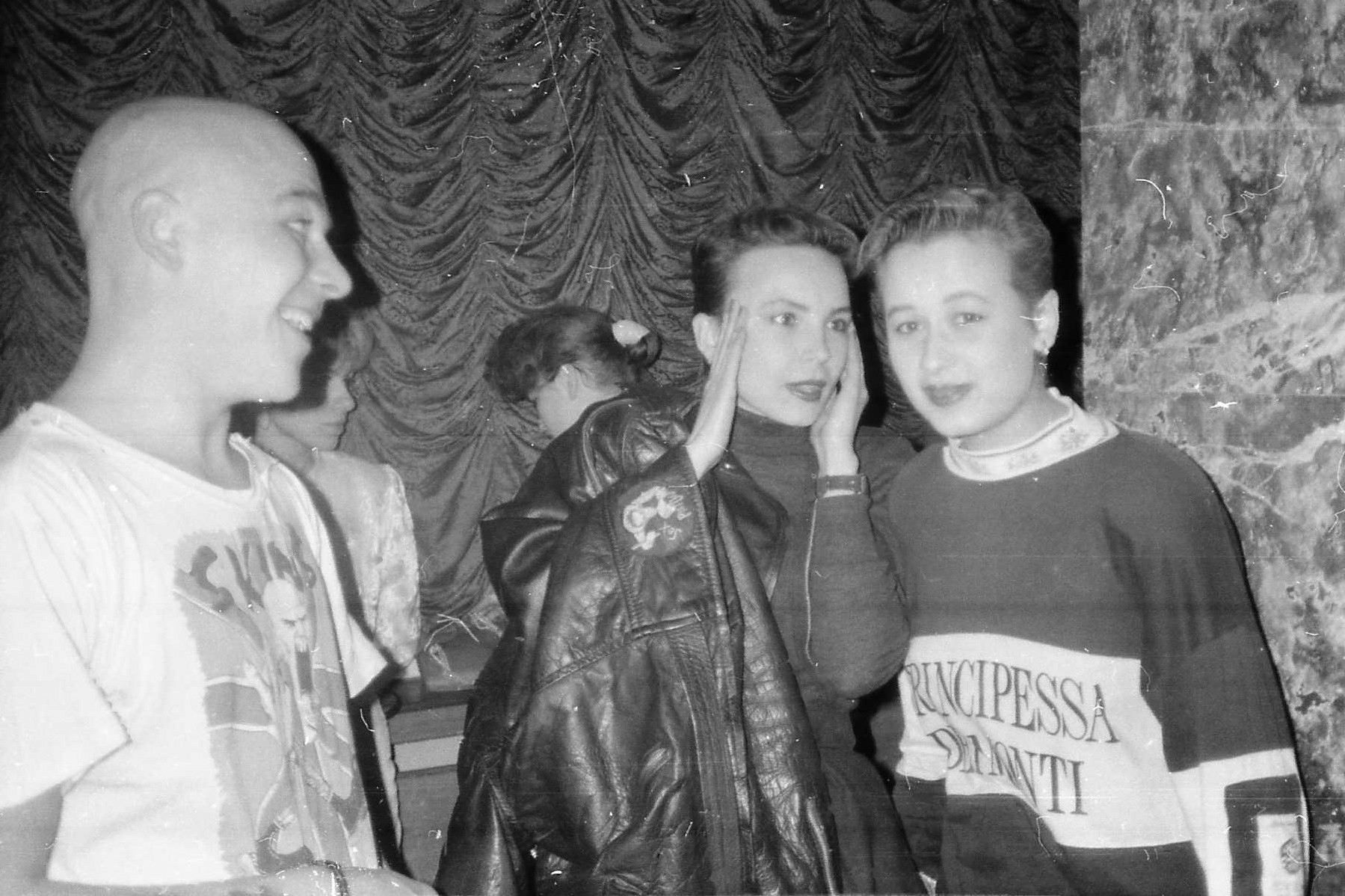

“Laminated nylon Adidas, a fluorescent nylon shirt, vinyl Diesel brand jeans, and a backpack slung over his shoulders,” begins a news story from the St Petersburg Newspaper describing the fashions of the city’s young ravers in the mid-90s. “The banality of endless repetitions, and a lack of concrete structure in rave music has the ability to translate into uniformity in clothing style… These young people wake up in the evening, brush their teeth, and, having covered themselves in synthetics, head for the clubs. Most of them can’t crawl out of bed without having taken a pill or snorted some cocaine.” Young people in love with drugs and rebellion, wearing fashions the adults don’t understand, doing silly dances to endlessly repetitive music; these things are pretty much universal.

St Petersburg was built by Peter The Great as a new Capital city to bridge Russia and Europe on the Baltic. The baroque metropolis has always had its western ambitions at the core of it’s identity. Displacing Moscow, it was the country’s capital from its founding until the Revolution in 1917 that ended Russia’s Imperial Romanov dynasty. In the communist era, with Moscow the country’s capital again, the city became a hub of Russia’s rebellious art and musical underground. Home to squats and punks and avant-garde artists, after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, St Petersburg naturally opened up to the world, and in flooded Big Macs and blue jeans and yes, the endless banal repetitions of rave music and its associated sartorial choices.

As a designer, Gosha Rubchinskiy — a native of St Petersburg — has, like his hometown, always blurred the boundary between Russia and Europe. The rave and skate scenes of the city was where he came of age, and was part of the inspiration for his spring/summer 18 collection, shown in the city two weeks ago. It was all about the power, universalism and rebellion of the tribalism of youth; whether that was ravers, skaters or football casuals decked in out in Burberry.

The rave element is the least well known. Casuals? Well, we invented that. Skaters? We’ve been letting Gosha’s lens illuminate us on the St Petersburg’s skate scene for almost a decade now. Ravers? Well luckily it’s the subject of a new, limited edition book, the designer has created with INRUSSIA: featuring contemporary essays and oral histories that track the birth, rise and decline of the scene alongside a comprehensive photographic documentation of the people and parties of the rave scene.

The opening essay by artist and theorist Timur Novikov — who died in 2002, and whose work Gosha has used before in a capsule collection — details the scene’s history. He describes how he discovered rave music after running into Berlin techno pioneer Westbam in the mid-80s in Riga, and made the first attempts to bring the scene into the country, and also provides a potted history of the Western club scene for Russian readers. It takes in, in its journey the queers, freaks, hippies and punks who built the city’s scene, in forensic and sociological detail.

It picks up the story of the era in an oral history that takes in Denis Oding — founder of Tunnel Club, the hub of the scene at its peak — and Igor Vdovin, one of St Petersburg’s leading producers of rave music. “St. Petersburg raves in the 90s were a meeting point for artists, mods, attractive young people, creative girls, prostitutes and criminals,” Denis recalls. This heady mixture led to multiple raids by the authorities on the clubs, and a sense of danger alongside the freedom offered by the music. Denis writes of a time they barricaded themselves into Tunnel, which was easy, because it was housed in an old bomb shelter. The police got pretty angry, arrested one DJ, punched the teeth out of the other, and made all the clubbers stand out cold St Petersburg night for hours.

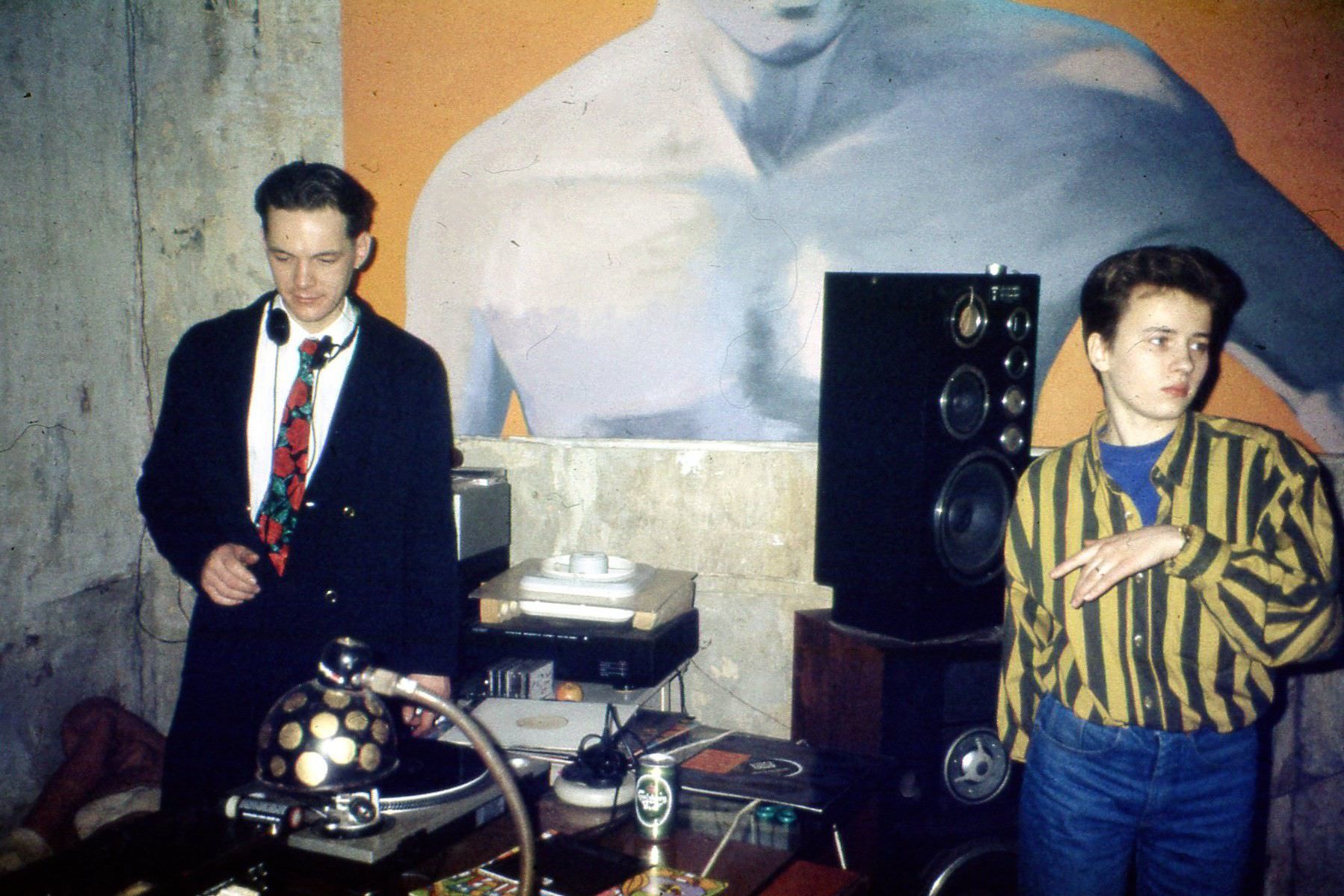

It was a make it up as you go along scene, where necessity met invention. In the book, the scene’s leading female DJ, Lena Popova, writes that it was almost impossible to even get access to turntables, let alone records, as they were prohibitively expensive. She estimates they were four or five in the whole city, and about ten DJs.

But, despite this backdrop of police violence and lack of equipment, what propelled the scene in its unique direction, and made it so legendary, was the presence of artists. With few clubs most of the parties took place in arty squats. Timur Novikov and Georgiy Guryanov were the leading artists of their generation in Russia, and it was their dedication to the new sound of rave, alongside their promotion of the city’s art scene, that turned the art squats into wild all night clubs at the tail end of the USSR.

The first squat-club, Fontanka 145, was run by artists dedicated to existing outside the confines of Soviet Russia. They moved into an abandoned apartment, knocked down the walls to create a dance floor, invited artists to create the club’s decorations. It was in Fontanka 145 that Russian youth could hear Western records for the first time courtesy of Alexei Khaas, the club’s DJ. Eventually Fontanka 145 was closed down, and Alexei and his brother opened Tunnel Club, which became the scene’s new centre.

Tunnel went down in history for its crowd, a combination of avant-garde youth, bohemians, club kids and queers, and less savoury criminal elements and mobsters. But as the USSR collapsed, suddenly everything became free. “The borders were opened,” Photographer Igor Bystriy writes. “And new electronic music poured in, forcing out the communist hymns and pioneer songs we had grown up on. It was so dope! Just look at my photos and you will see how good everyone felt.” As Tunnel grew in notoriety, so did the scene, and it became bigger and more commercial.

“It was hard not to notice that the public was changing,” Denis recalls, off the scene’s creative demise. “From our friends, DJs and musicians, or just cool kids, to complete strangers. It all started when criminals began visiting Tunnel and scared our friends away. It was scary to be in the club, even for us… The movement had turned into a trivial commercial matter. We grew tired of each other. The final straw came with the introduction of restrictions that placed music festivals on the same level as events associated with drug distribution.”

Like most scenes, it was underground, went mainstream, went commercial, was over. But it’s a moment still relatively under-reported and undiscovered in the west, at least till know, as the current generation of Russian youth start to turn towards their own history for inspiration, reevaluating their creative, underground, past as fertile inspiration to navigate the present. Gosha might be the leader, but he’s dedicated to showing his research, and his country, to the world too.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography I Bistriy. Images courtesy INRUSSIA