This article originally appeared in The Sounding Off Issue, no. 350, Winter 2017.

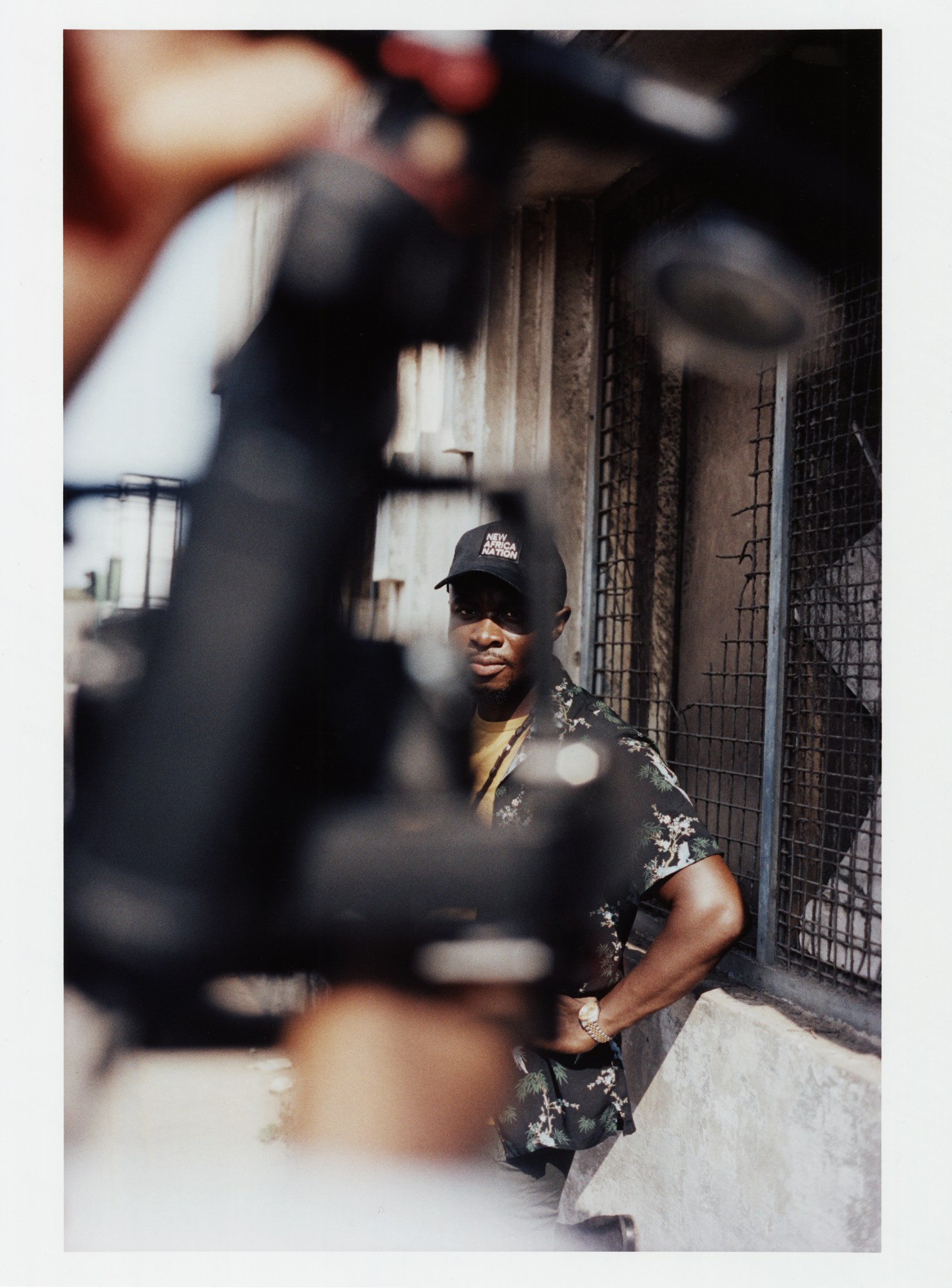

Fuse ODG, 28, musician and activist With New Africa Nation, both an album and a movement, Fuse is committed to changing outdated perceptions of Africa.

It’s midnight in Accra. The BBQ-turned-house-party that’s been going on since sometime this afternoon has suddenly come to an abrupt halt. Everyone has congregated in the upstairs studio of the bright yellow ODG mansion. Situated in the affluent area of east Legon (President Nana Akufo-Addo lives down the road), it’s the house owned by Ghanaian-born, British-based pop star Fuse ODG, aka 28-year-old Nana Richard Abiona, who’s also the man behind the party. His house is inhabited by a motley crew of musicians and producers, and frequented by activists, celebrities (Ed Sheeran popped by last year), and this week, i-D. Tonight, the room is filled with journalists, bloggers and some of Ghana’s most influential musicians. “New Africa Nation” is emblazoned in white paint on a black wall. Six bottles of Moët stand to attention on a table.

“When I first landed in London as a kid, I was put in these categories,” Fuse announces to the group of 30 or so. “I was ‘Black’ or ‘African’. At school [in Mitcham], kids thought I’d come from the jungle. I couldn’t understand where they got their information from, but then I’d switch on the TV, and the only Africans I’d see were in charity appeals showing kids with flies around their mouths, or young black men at crime scenes.” The room – which 10 minutes earlier was the scene of feverish dancing and raucous laughter – hangs on Fuse’s every word. “If we don’t fight for us, no one else is going to. I’ve seen how they talk about us out there. Love yourself, even if someone else is saying you’re not worth shit. We have to realise our value.” A riotous cheer fills the room. The champagne pours once more and the music continues to pulsate through the house late into the night. If Fuse’s fight is to promote a greater and fairer understanding of Africa, Afrobeats is his weapon of choice. An umbrella term for up-tempo music with roots in traditional African highlife, Afrobeats has grown in popularity both in its native West Africa (Nigeria, Ivory Coast and Ghana all have strong scenes), and in the UK. Where grime and road rap were born out of disillusionment and frustration, Afrobeats’ defining quality is its unwavering commitment to fun. Dancing isn’t a by-product, it’s mandatory, and humour is often central to songs.

Case in point: Date Your Fada by Ebony Reigns is one of the songs that follows us around Ghana. ‘If you break my heart, I go date your father,’ the singer taunts over an irresistibly percussive beat. “You gonna be my son, you go call me your mother.” When half the world’s news resembles dystopian fiction, music from artists like Ebony provide a strong argument for swapping screw-faces for smiles, and embracing the optimism Afrobeats offers.

Despite being bleary-eyed and hungover Fuse insists the next morning starts with a run. It’s not the worst idea; east Legon is a residential neighbourhood but in the mornings it’s leafy and vibrant, and as we run we watch small stalls and shops set up to sell everything from party dresses to joloff rice. Fuse leads the way, weaving through street sellers and parked cars down roads are lined with swaying palm trees. Following Fuse is King Promise, a handsome and softly spoken singer, and Joseph Addison, known as Killbeatz, one of Ghana’s most prolific producers, and a key player connecting the musicians we meet during our visit.

In the afternoon, we head east to Tema, where Joseph grew up. After walking through a maze of narrow alleyways we’re led to a small house made up of three rooms. One is practically bare apart from a single mattress on the floor and a small TV. “This is where it all started,” Fuse says, reminiscing about the rooms’ former life as Killbeatz’ first studio. “The whole group grew up together here,” Killbeatz explains. “We’d spend whole nights freestyling in this room.”

After messaging over Twitter in 2011, the pair met in Joseph’s makeshift studio to record. “I’d decided to go back to Ghana to reconnect with myself as an African person and soak up the vibes,” explains Fuse, who lives in London but takes regular trips to Accra. “I came to make music, but I rediscovered myself. I hadn’t been to Ghana since I was 11, so when I landed it became personal.” The trip marked the start of a lasting relationship, the two worked together on Fuse’s early crossover anthems Azonto and Antenna. “When you listen to those songs,” Killbeatz says, “you hear pop and Afrobeat, ” he starts humming the chorus to Antenna. “It’s an introduction to the world. Like, ‘Pop, this is Afrobeats.’” When Fuse brought Ed Sheeran to Ghana, he too got in the studio with Killbeatz, recording Bibia Be Ye Ye ( All Will Be Well) for his album, Divide. “That was a good experience,” he says. “The album went to number 1 in the UK. Big things are about to happen over there with our music.”

Sure enough, Afrobeats has been Azonto’ing its way into British dance music for almost a decade, and in recent years, crossover hits like D’Banj’s Oliver Twist and Fuse’s Antenna have been instrumental in delivering West African sounds to a wider audience. Last year, Nigerian artist Wizkid cemented his status as a fully-fledged pop star after collaborating with Drake on the Afrobeats and dancehall infused One Dance. With club nights, playlists and dedicated shows on platforms such as BBC 1Xtra, Spotify and Rinse FM, Afrobeats – or Afrowave, Afrofusion and other music of West African origin – is flirting with mainstream recognition in the same way grime broke through before it.

Over in Ghana, radio is equally vital. Over 30 competing stations broadcast Afrobeats out of Accra alone, “It’s very intense,” says Ms Naa, who drops by Fuse’s house later that day. The exuberant presenter of YFM’s breakfast show, Ryse N Shyne, Ms Naa rocks up to the mansion one evening and is so hell bent on having a good time she manages to sleep through her show the next day. “Radio can be cut-throat,” she grins. “We’re always competing to play the best music, I just try to make it wild and have fun.” Show’s like Ryse N Shyne are played, loudly, on tro tros (privately owned vans or minibuses), Ghana’s most widely-used transport system. “On the tro tro we hear everything,” King Promise says. “If your song gets picked up by the local stations, you know you’ve made it.” So fast is the process that a track might be recorded in Fuse’s mansion on a Friday, and be blasting out of a bus on Ms Naa’s show by Monday. It’s an appealing system, but several people point out the insidious corruption. “The royalty collection association just give you enough to shut you up,” Fuse explains. “[Influential Ghanaian rapper] Shatta Wale went with his people and held [someone] hostage demanding his royalties. Artists are definitely rebelling.”

Fuse wants to use his experience in the western music industry to help educate artists about publishing contracts and radio royalties. In Ghana, the majority of a musician’s income comes from performing, and in January, with the help of industry figures like Ms Naa, he plans to stage the first TINA [This is New Africa] festival in Accra. “It’s a platform to bring the diaspora together. To bring Africans and people who love our culture to Ghana for a great cause.” He pauses, thinking it over. “Like Africa’s version of Glastonbury!” Creating a meaningful music industry in Ghana is just one part of Fuse’s multifaceted mission. A large room at the back of his mansion houses a dedicated team of workers who make ‘Nana dolls’, black Barbies named after African queens, so that worldwide, children can see themselves represented in the toys they play with. Then there’s the primary school in Akosombo, a two hour drive from Accra. Set up with funds raised by Fuse and his manager Andre in 2007, it’s vital in providing education and accommodation for local children. He’s currently fundraising to build a secondary school on the same site, so that its students don’t have to walk miles to a neighbouring town. These projects all fall under the New Africa Nation banner, also the name of his forthcoming second album. It’s not just an album title, but a movement and a mission. It may be devised by Fuse, but it’s a shared goal pushed by everyone we meet in Ghana. “It’s happening. The time is now,” Fuse says. “Let’s work together and turn this mentality into a reality.”

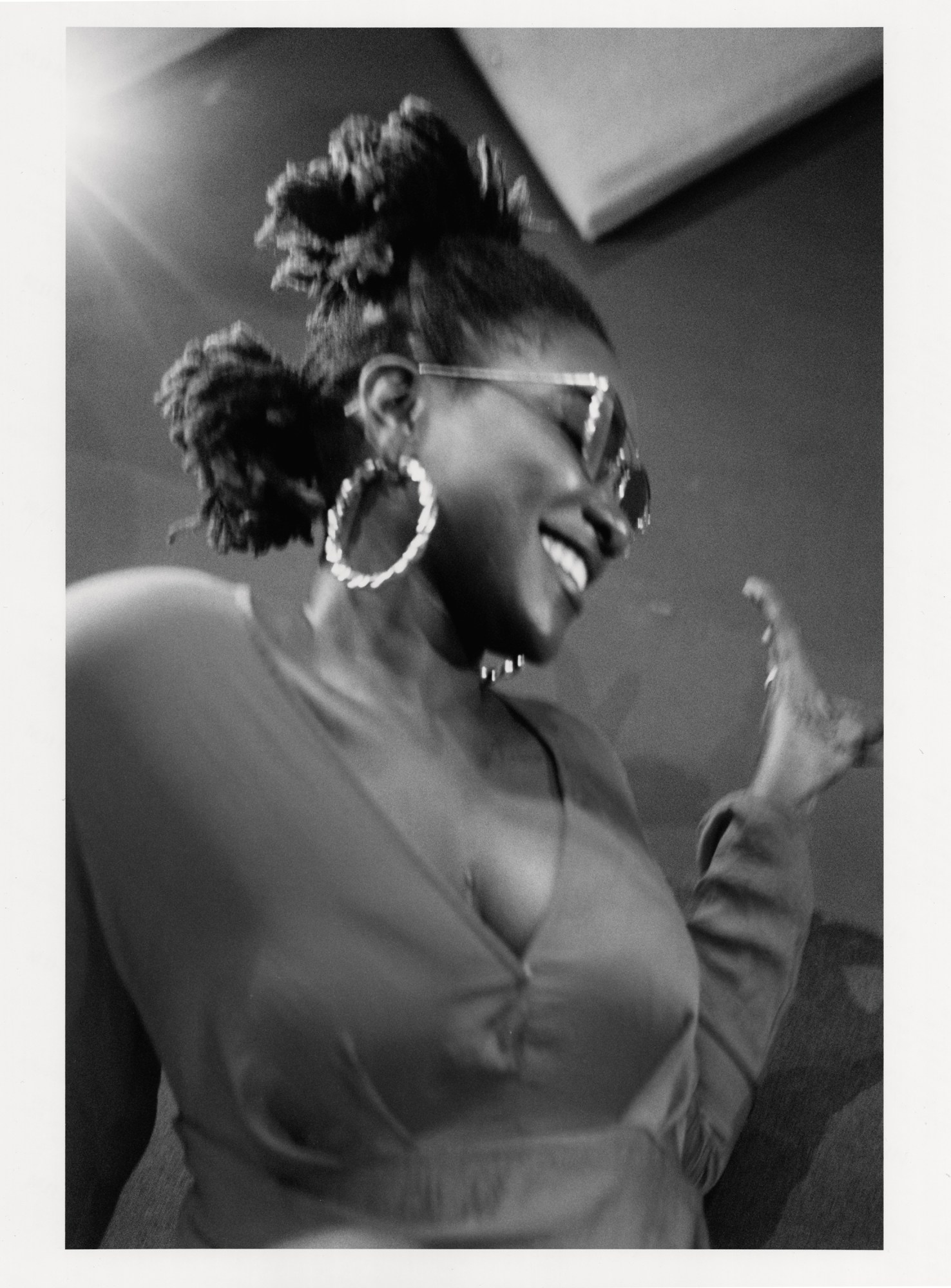

Ebony Reigns, 24, singer Soul singer Priscilla Opoku-Kwarteng is here for the women.

We’ve heard your music all over Accra! If you listen to my songs, the story lines are about what goes on in society. Does someone have a sugar daddy? Is this person cheating on their girlfriend? Most of the time, I’m out here talking for the ladies because I’m a feminist. Do you think there’s any extra challenges being female in the industry? It’s still, like many things, very male dominated. My experience wasn’t difficult at all, but I know female artists who go through a lot, who have had people deceiving them to try and sleep with them. But I focus on the music and performing. I feed off the crowd’s energy. Audiences in Ghana get crazy, and when they’re wired I’m like, ‘Ebony, they are here for you!’ It’s just crazy. I love being on stage. What do you do when you’re not working? I like to stay home and hang out with my girls. My circle is very tight, there’s three of us; we write music, have fun, chill out, talk and drink.

King Promise, 25, singer Prepare to fall for the Afrobeats prince.

What’s so special about Afrobeats? The rhythm and the vibe. It brings you joy, it sparks something inside you. They say music kills pain, it helps you forget about your sorrows. We also listen to music to have a good time too, music is life. What makes your music different? Well, the first thing you notice is this bald looking head, I can’t hide, this head gives me away. I used to do a lot of R&B but I’ve kind of switched to Afrobeats. I don’t limit myself to any one genre, but I take songwriting seriously. My single Oh Yeah went to number one! It’s me professing love to a girl, I’m celebrating the beauty of African women, of all women. I’m being a bit lovey-dovey, but there’s a story to it. What’s nightlife like in Ghana? When I go out, I go out. Twist is the number one club in Ghana. All the big shots go there, you see Lamborghinis and Rolls-Royces parked outside, the music is great and everyone is there to have a good time. Sometimes I want to look like a rapper, so I switch it up. We stay at the club till the next morning. Come on, Chale! Why would you go to sleep? What is sleep for?!

Toy Boi, 21, rapper Meet Brian Martey, the multilingual boy ready for world domination.

What’s the Toy Boi USP? I rap in English and two different Ghanaian dialects; Ga and Twi. I fuse them, I make them sound like a compact work. Stormzy retweeted one of my freestyles the other day. Why do you rap in three languages? They’re two big languages in Ghana, and I don’t just want one side listening to my music, I want everyone to hear it. Who are you working with right now? Killbeatz. We have a single he produced out now, Somtin. When we started working together it felt right, we make good music together. Where’s the best place to go out in Accra? I’d say the beach. And the clubs: Twist, Soho, Carbon, Purple Pub. J Hus was in Ghana and that’s where he went. It’s an open place, it’s for everyone, you can get food, drink. It’s kind of like a festival, all kinds of people are there just jamming.

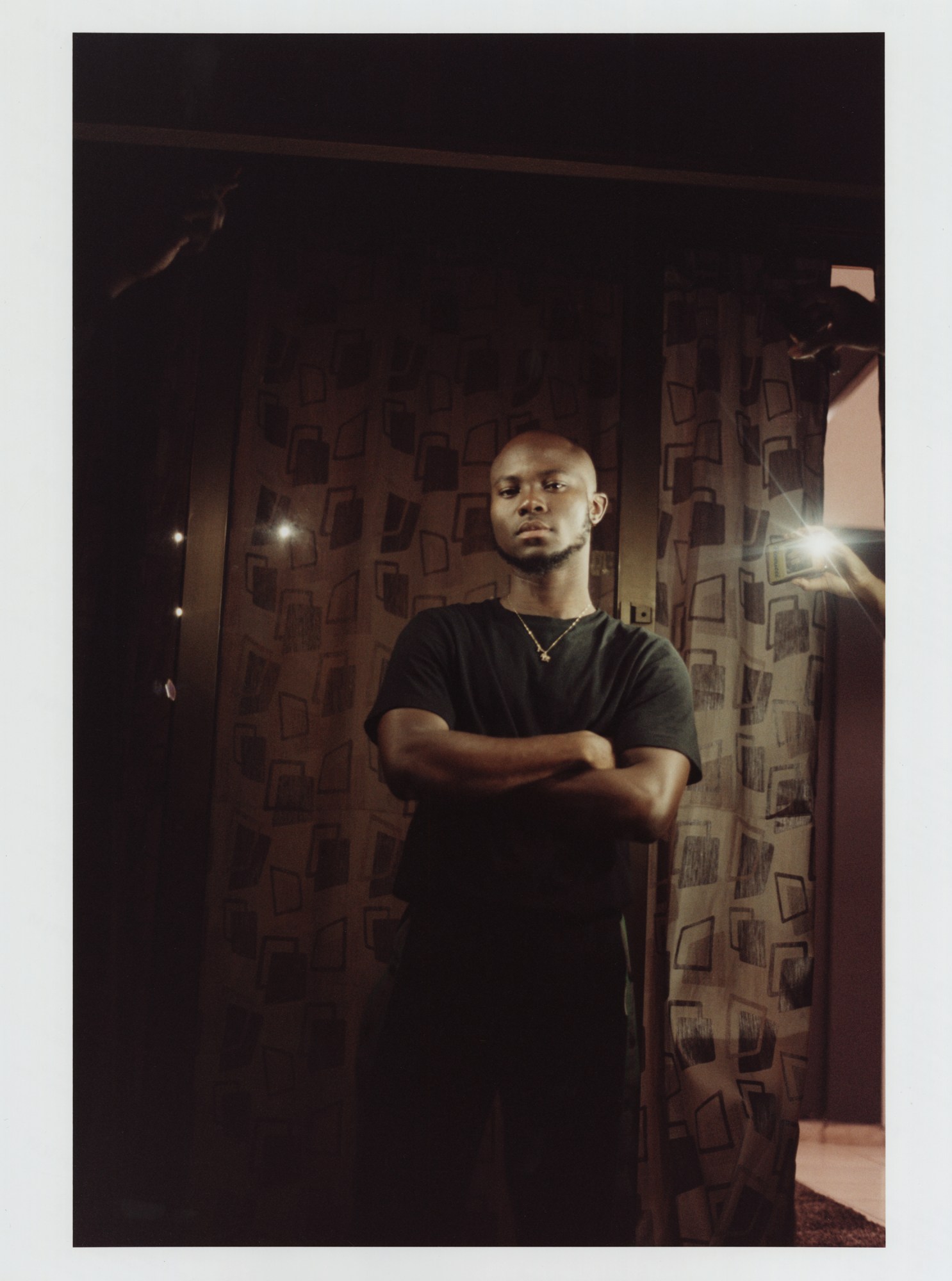

Killbeatz, Producer Influential producer Joseph Addison is a driving force behind the Ghanaian Afrobeats scene.

What was it like growing up in Tema? No one has anything, but growing up you learn that no matter how hard it is, you stick together. You see a lot – prostitutes, mentally ill people – one of my best friends died in prison last month. It’s a crazy vibe, but thank god we survived. Music is the main thing, it kept me focused. How did you get into music? My home was very musical. My father was a pastor and I used to play the piano in the church band. In Africa, when someone dies you do a funeral in the park and the band play local highlife songs. Non-Africans see it as a celebration, but it’s more a last respect for the person. I listened to a lot of hip-hop so sometimes I’d think of raps that go over the music. When did you become a producer? I taught myself to do beats on the church keyboard. I’m from the same neighbourhood as R2Bees and I started producing them. Gradually, things just blew up. Why Afrobeats? We didn’t plan this, it was never about making money, but when people started taking it seriously, we realised we needed to take it seriously. I can do hip-hop and reggae, but everyone knows that. I’m the leader so I want to stick to Afrobeats. People need to know there’s something deeper, people need to know we’re here.

Credits

Photography Campbell Addy

Retouching and processing Chan Photographic Imaging.