Now’s as good a time as any to discuss gender politics in relation to men’s fashion; in fact, it’s probably one of the best. Currently, in the theatre of menswear showcases, designers aren’t exactly calibrated to mainstream thoughts on men’s performance of gender, which is still a little archaic, though improving. The clothes proposed for the next season truly are speculative in every sense, given (so often) their lack of grounding in reality. To the layman, menswear season is still nothing more than a trolling in a newspaper to mildly bemuse the commute away.

While several of the most powerful voices offered deliberate glimmers of pedestrian reality this season — namely, Prada, Balenciaga, Gosha Rubchinskiy, and Louis Vuitton in its collaboration with Supreme — there were also many hyperboles of dress far removed from the streets. Two tropes in particular emerged repeatedly for the season. One was a sensual man, whose body was seen through classically feminine cues like diaphanous fabrics, drapery, and ornamentation. The second was more coded — a traditional masculinity undermined by details of feminization and imperfection. These could be packaged as “trends,” but truthfully, it felt less contrived than this — more identity than whim. Which leads onto the question: are these the characters that best offer the prognosis for tomorrow’s masculinity? Or, more realistically, when will we finally allow them to be?

Perhaps one of the most impactful and widely circulated images of this season was of a male model in a red-carpet gown walking at the Vivienne Westwood show during LFWM. A sheer, corseted, black dress with a mini-skirt slip and a ruched sash sleeve. It was not so unusual coming from Dame Westwood’s husband and design partner Andreas Kronthaler, given the couples’ significant imprint on New Romanticism, and gender bending. But this collection drew special attention to the latter topic, as it debuted the union of menswear with the womenswear Gold Label, and the genders interplayed each other throughout.

There’s an intriguing sexiness about tulle, and other gossamer fabrics. In their haziness, they imply a potential for seeing a body, and create an indefiniteness about what lies beneath. The gender-fluid collective Art School did it through a sporty fishnet at Fashion East, alongside tulles and shimmering crystals across a cast of trans, queer, and non-binary non-models. Drapery and ruching also have erotic effects, and were seen from the likes of Ann Demeulemeester, Rick Owens, Wales Bonner, and Charles Jeffrey LOVERBOY. Both techniques fully disguise the body, while still performing human curvatures and contours. They hinge on the erotic idea of the body moving between and beneath the fabric, which in itself, is not a familiar signal thrown out by the typical, heteronormative man today. Our conditioned dynamics of courtship place the man more as the predator, the seeker, not the shy ingénue.

Wales Bonner, as ever, played with degrees of masculinity, featuring poetic drapes of white linen, skirt silhouettes, and crystal adornments. Her take on what she called “very renaissance effeminate guys and then spiritual figures all in white” implied a shift from corporeal emphasis to something transcendent — even ideological, for the spiritual figures. It was a similar move for Feng Chen Wang at MAN. The designer’s signature manipulations of utility clothing moved away from their ties to the physical world, and into, as Wang described it, “this realm of impressions and feelings.” Fleshy leather and second skins were used, and glittering silvers, and Wang’s gatherings of material into rolls and puffs here had a suggestion of contorted nude bodies. She considered it, in its enshrouding size, to be cocooning, “reflecting a fundamental human need: to feel safe.” It was, again, another departure from a male-aggressor, and into an expression of vulnerability.

It felt significant that both Wooyoungmi and Alexander McQueen collections drew inspiration from Oscar Wilde. The reimaginings of the dandyish aesthete — and homophobically-motivated reject in later life — spoke to a certain wilfulness of self-expression, and beauty, against adversity. And in a similar vain at Loewe, Jonathan Anderson continued his essays on intellectual, romantic, sensitive clothes. A contrast of heavy drapery with exposed skin, adorned with little wood-carved trinkets, had a tactility about it that felt fundamentally human and emotionally charged.

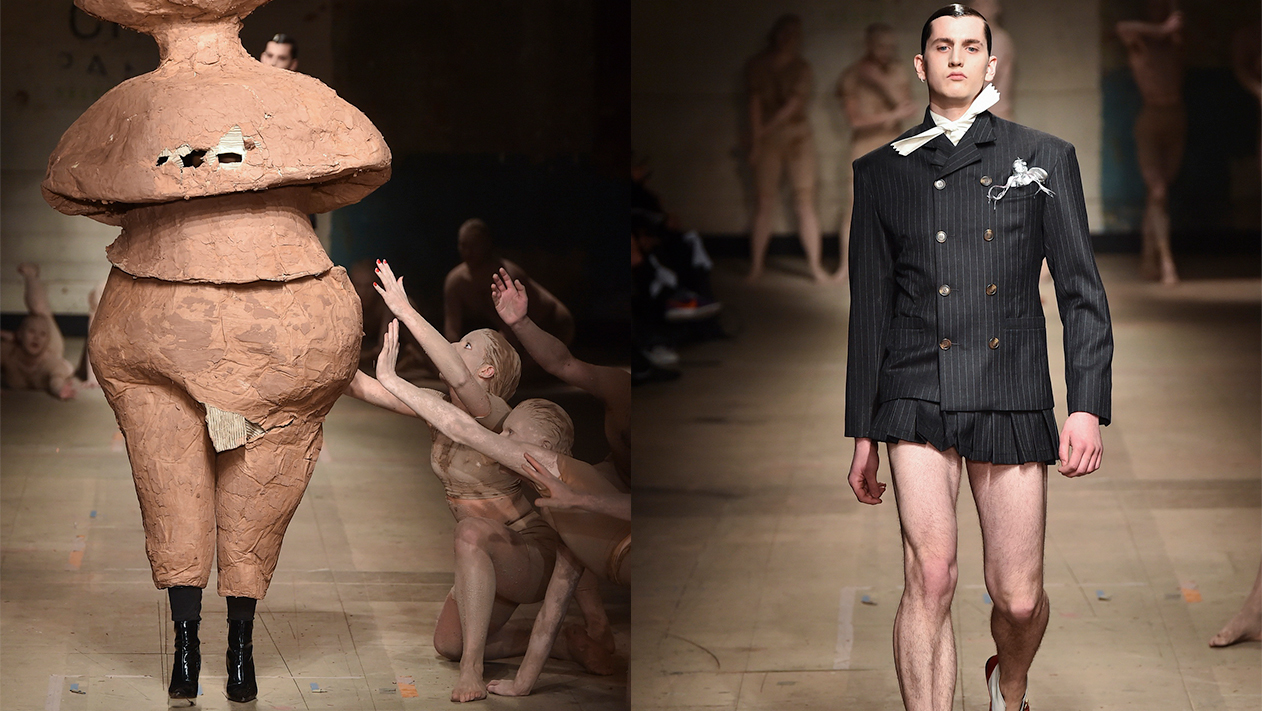

The second trope, of coded, perverse masculinity was spearheaded perhaps, by emerging London designers, of the likes of Martine Rose and Xander Zhou, the latter of whom’s collection was entitled, I’m Carrying a Secret Weapon. Tailoring was done with wonderful ugliness: Pepto-Bismol and mustard shades, suggestively exposed skin around the hips, eyes, and hands concealed, greasy hair, cream mohair turtlenecks, and trench coats (which have their own special sexual suggestion). At Martine Rose, the trench coats were cut with halter necks. The whole agenda was the undermining the archetype of the professional male with effeminate and fetishistic details: satin shirts, leather trousers, cinched waists, exposed zippers on pale yellow jeans. They spoke to a feeling of defectiveness, of being a part of a uniformed collective but still misaligned, which all say something about today’s concussed state of self-expression.

With Comme des Garçons Homme Plus, it was the same technical notion: tailoring perverted with femininity or child-likeness that bleared the sharp lines of the suit. The cast of lithe white boys in sherbet-colored microfibre wigs, with their abs exposed, called to mind cosplay, and by extension, the larger aesthetic Japanese movement of bishōnen. Perhaps, for this reason, the effect felt different. It’s a cultural stratification, where in Japan, there’s the mainstream capacity to appreciate a man for his delicateness, youth, and androgyny.

It’s hard not to think about the pressures placed on men to perform a very narrow vision of their gender — and one that might not be their most authentic vision of themselves. It’s led to some urgent campaigns in recent years focused on men’s mental health stigma, given the socially emphasized embarrassment of admitting flaw, and feelings. In terms of developing varied truths of identity, even now, some high-street brands are beginning to broach the topic. Unisex and androgyny are being addressed, like with Zara’s “Ungendered” collection last year, but it just ends up being a cotton-jersey glob of cultish boringness that hides bodies and chucks away all the amazing intensities of masculinity and femininity, and the beautiful realms between.

In summary of the collections, it was a season consumed with addressing fear. Political fear, obviously, the threat of corruption at the turn of adulthood (Charles Jeffrey LOVERBOY), the vast, emptiness of the sea, and whatever that might signify to you (Craig Green). But the designs themselves offered optimistic visions of a more diverse, willful, and authentic time ahead. Near the end of menswear showcases, in Paris, Ann Demeulemeester presented a Victorian-esque gothic realm. An androgynous slew of boys and girls in dusty pink silks, sheer lace, feathers, and strings of velvet. It was so vividly a portrait of the past, but the models had the word “l’avenir” roped around their necks. “The future.” Let’s look forward to the perpetuation of a more colorful experience of identity, faint on the visible horizon. Of dramatizing a spectrum of emotions, volitions, and vulnerabilities. Here’s to holding on for tomorrow.

Credits

Text Kinza Shenn

Photography Mitchell Sams