Just over two years ago, Facebook introduced a whopping 58 gender options for users who didn’t identify as “male” or “female.” The number soon rose to 71 — including asexual, polygender, and two-spirit person — and today there’s an option to create your own definition. The idea of gender as a construct is complex, relevant, and ever-expanding. This is the premise of Façadomy, a new zine about themes in modern identity by Brooklyn-based graphic designer Riley Hooker. The inaugural issue, Gender Talents, has just been funded through Kickstarter, and explores self-determined gender through the lens of art and architecture. Hooker is also a member of the House of Ladosha and deeply immersed in the city’s radical queer art scene, signing up two of Façadomy’s first three contributors from his diverse social circle: downtown art queen Juliana Huxtable and badass art tastemaker Kimberly Drew (aka @museummammy). The third contributor is Andreas Angelidakis, a Greek architect whose work is found primarily in museums, and who excitedly took up Hooker’s offer while vacationing on a tropical island.

Façadomy: Gender Talents itself builds off the work of Esben Esther P. Benestad. Dr. Benestad identified seven gender categories in their practice as a progressive sexologist in Norway, though Hooker notes that their work is only an entranceway to understanding gender as transmutable. i-D spoke to Hooker about race, power, and why the work of a 67-year-old Norwegian physician is so relevant to American youth now.

What is your personal experience with self-determined gender?

I’m a cis male, so I myself haven’t really dealt with these issues from the inside out. But I’ve been very active in the radical queer community for about 15 years. When I was in art school in Minneapolis I worked for an experimental queer film festival. Watching all the films, I was exposed to a lot of these more progressive ideas about gender. One of my best friends is trans. When I met her she was visibly genderqueer, but fully embraced the transition to identifying as female over the course of our friendship. She’s also a person of color, and a lot of the microaggressions that she experienced — even within the queer community — had a lot to do with issues of race and class and all of these other dynamics that, as a cis white person, even though I’m queer and have invested a lot into that identity, were totally invisible to me. People so often have to suppress a lot of suffering. It’s a privilege to have your complaints taken seriously.

Your publication builds off the work of progressive sexologist Esben Esther P. Benestad, who identified seven genders. Why did this appeal to you?

I saw Dr. Benestad on a panel at the New Museum that was part of Carlos Motta’s program “We Who Feel Differently.” I thought the seven genders theory was a really interesting approach. Humans are obsessed with categorizing things, and I think equally obsessed with breaking down these barriers once we put them in place. The idea of self-determined gender is a really abstract notion if you haven’t experienced it yourself. To take a concept that’s typically binary and say, “Actually, no it’s everything,” is really destabilizing for a lot of people. I think seven categories is a great way to show the breadth of something. The categories are a great entry point and a great way to make this idea accessible.

I guess another thing to make clear with my approach to this project is that I’m not proposing that these seven genders are the seven genders. It’s one of so many ways of looking at this. The important thing to me is that the agency of determining gender be put in the hands of the individual, and not be determined by doctors. Dr. Benestad’s approach is just documenting the different ways in which people respond to the question, “What is your gender?”

How did you connect with the three contributors, Andreas, Kimberly, and Juliana?

I funded the preview edition of Gender Talents out of my own pocket so I mostly stayed within my own social network for the contributors. Juliana Huxtable is a long-time cohort and close friend of mine. We came of age together, in a sense, and found our voices through the House of Ladosha — a loose-knit artist collective in New York which has functioned like a family for us. Personal affiliations aside, I needed someone who understands gender in a way that could be sentient, otherworldly, and authoritative all at once. I mean, who else?

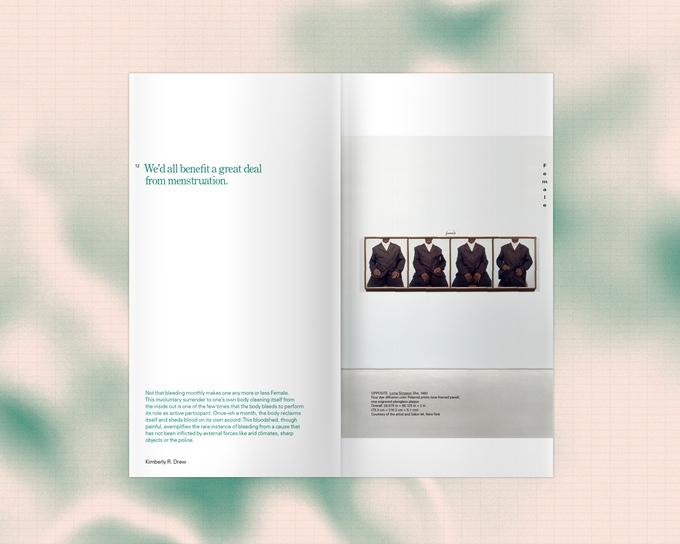

I’ve always admired Kim Drew’s ability to get at the heart of a complex issue without overdoing it. It was important for me to include the intersections of race and class with gender and her work does that with a wit that is cool, direct, and just enough.

Andreas Angelidakis is someone I had been obsessed with for a while. He’s a real gem in the architecture world because he doesn’t have an ego and speaks like an actual person. He has a poetic mind and can go to that place somewhere between kitsch and avant garde and come out on the other end with something salient. The layout is like a polyphonic visual essay, and wouldn’t have worked without Façadomy’s copy editor Joey De Jesus — he really went in.

The three of these contributors know first-hand what it’s like to inhabit a politicized body. As an editor, it’s really important for me to craft a narrative that champions and really utilizes the perspective of underrepresented voices and people who do inhabit politicized bodies. It’s not about filling a quota of these underrepresented voices, which a lot of institutions are now doing. That’s great, but it’s problematic, because unless this diverse point of view is coming from the inside out, you really are just trying to fix the hole in a larger problem. I saw an opportunity to craft a narrative that is designed for that point of view to shine and be utilized.

What demographics have shown the most interest in the project, both at the NY Art Book Fair last September and through the Kickstarter campaign?

Obviously the queer artistic community has been really supportive. The larger artistic community has also been very supportive. The biggest surprise to me is the support I have received from the architectural world. I’m not an architect. I’ve worked with a lot of them as a graphic designer, but I’m not super well-versed in the kinds of issues that architects are used to talking about. I think architecture is at a point where they’re thinking less about buildings and more about what buildings and cities can facilitate. The buildings that we inhabit, and the objects that we use, reflect ourselves, and are more often than not a manifestation of our own desires. I think Façadomy gives people in the architecture profession a way to enter this complex web of social ideas.

Credits

Text Hannah Ongley

Images courtesy of Façadomy