When people consider the terrible consequences of war, they don’t usually think about the slow deterioration of romantic love. The images we are used to seeing often desensitise us. They are of bombs exploding, machine guns rattling and people in awful, possibly unimaginable pain. Sitting in relative safety in the West, how much can any of us really understand what is happening in Syria? When we look at the photograph of Aylan Kurdi, the dead Syrian boy washed up on the beach, what do we really see?

When I interviewed him in 2012, the filmmaker Sean McAllister told me that he wanted to take the Arab Spring to his “mates in Hull”. His new documentary, Syrian Love Story, which is about to be released in cinemas before being shown as part of the BBC’s Storyville series, was filmed over five years and chronicles the slow, heart-breaking breakdown of a relationship against the backdrop of the Syrian Civil War. It is a piece of work that recalls Ingmar Bergman and Ken Loach, rather than the News at Ten.

The film tells the story of Palestinian freedom fighter Amer and Syrian revolutionary Raghda, comrades and lovers who met in prison before getting married and having four sons together. Sitting in the bar at the British Film Institute, Sean tells me that he met Amer at a bar in the old city of Damascus. “Amer took a call and I asked him who it was from. He said it was his wife and that she was in prison… At that point, before the Arab Spring, I thought Syria was a relatively strong, functioning dictatorship”. Sean told Amer this was the film he wanted to make and Amer, who was wary of the British filmmaker, told him that if he wanted to know about the real Syria, he needed to come with him.

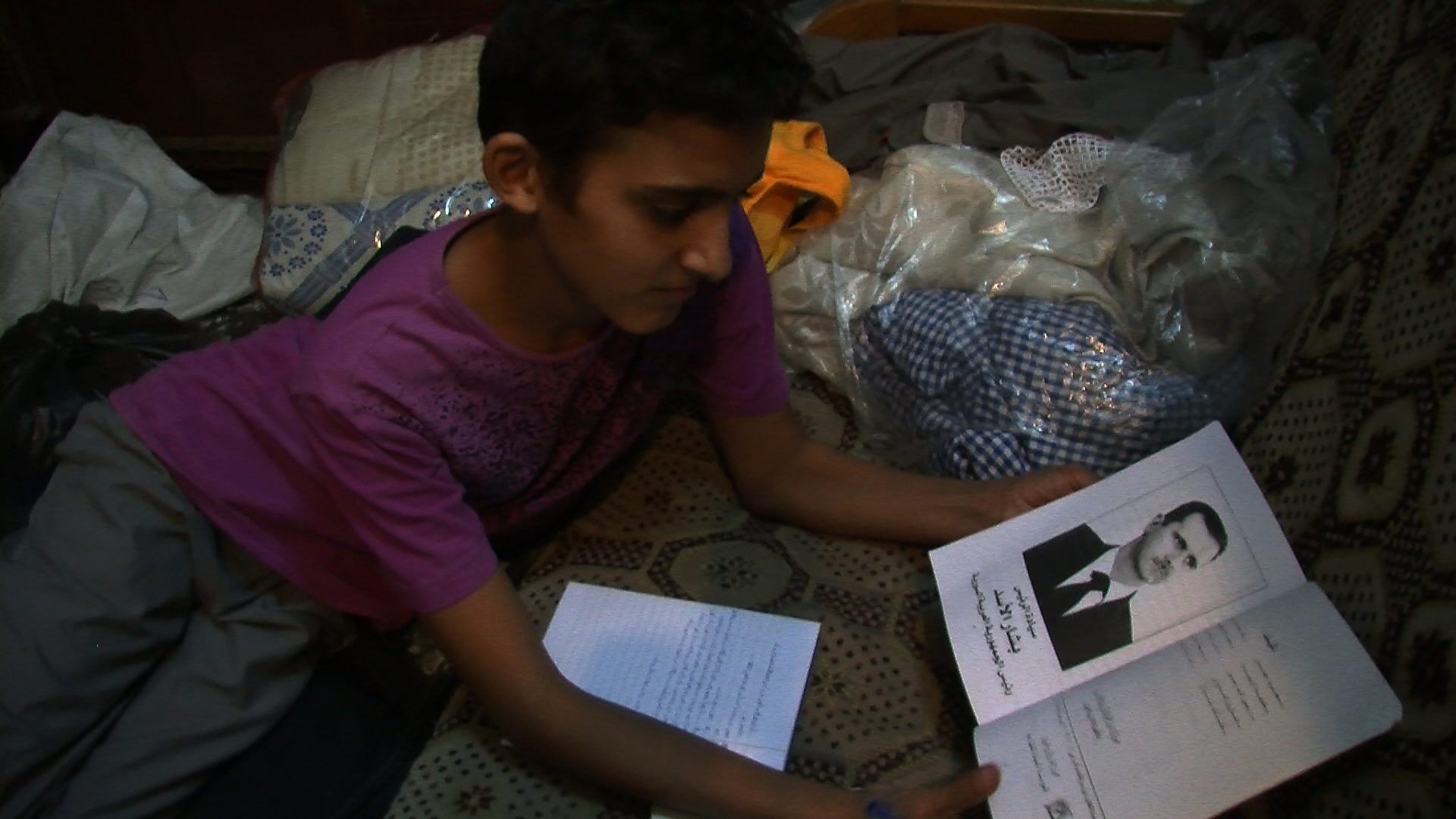

“Ideally, I want to find a character whose situation or complexities reflects the bigger picture”, Sean says. Syria was “putting on this performance in the square mile of the old city of Damascus, but scratch the surface and there were prisons full of political prisoners”. Raghda, the beautiful revolutionary, was one of these prisoners. In the seaside town of Tartus, we see Amer and his engaging sons sitting in their small flat, trying to bring about the release of their mother while going on as best they can with their everyday lives.

Following the outbreak of the Arab spring, Raghda is released and returns home. But prison has changed her and the intense pressure of living under a dictatorial regime has affected the whole family. “What was visible in the film is that she had post-traumatic stress”, Sean says. “You could see that she was living through the whole tragedy of prison. She couldn’t see clearly, about anything”.

Amer wants his wife to be a mother first and a revolutionary second. “She paid with her life before”, Amer says. “She cannot be Che Guevara and be a mother”. But Raghda cannot give up the cause. “I started before the revolution and I cannot abandon it now”, she tells her husband. The dream of a free Syria is one that Amer maybe able to step back from for the sake of his family’s wellbeing, but for Raghda, who has spent so long behind bars, it is all-consuming.

plays out over three acts, in Tartus, Lebanon and then France. Sean is picked up and thrown in prison by Bashar Al-Assad’s secret police – “They were whipping and beating the other people I was in prison with”, he says – and because of that the family must flee Tartus to a refugee camp in Lebanon. There, Raghda is left with an “empty feeling” and Amer feels as though his “heart is breaking every day”. A freedom fighter and trained killer, Amer sits in his kitchen and tells the camera that he loves Raghda, that all he wants is for her to come back to him.

It is in Lebanon and in France, as Amer and Raghda’s love is pulled apart by their trauma, that Sean’s vision of taking something universal and applying it to extraordinary situations is most apparent. Most of us have experienced the breakdown of a relationship, but very few of us have had that relationship break down against the backdrop of prison, civil war, repression and violence. But because Syrian Love Story stays with its main characters over 75 minutes, we are drawn into their world and the remote horror of what is happening in Syria begins to seem less remote.

Through all of this, Amer and Raghda’s young son Bob remains a central, charismatic presence. “When I was doing a Q&A in Latvia”, Sean tells me, “I was asked what I hoped for the film, and I said, ‘All I really hope is that when you look at that image of the dead boy on the beach, it’s no longer this empty image, it’s Bob'”. News coverage, for Sean, often fails to what it claims to do. It shows images, not people. “It’s like watching the weather. You watch it for three minutes and then at the end you turn to the person next to you and say, ‘So what’s the weather tomorrow?'”

For Sean, then, the challenge is still making a film that non-specialist audiences and his mates in Hull can connect to: “I used to work in factories and I wanted to know how you can begin to understand the complexities of places like Iraq or Palestine when you’re up at six o’clock in the morning hanging off the side of a ship, working your bollocks off and then coming home to watch the news. I don’t know but if you can watch a film where you meet people like Amer and Raghda, then I think you can begin to relate”.

In Syrian Love Story the bombs and the deaths and the politics are there, but they are in the background. In the foreground are ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. When the family finally make it to France as asylum seekers, owing to Raghda’s special status as a former political prisoner, the new life brings with it the ending of the relationship. “It was sad to me because they had both dreamed of freedom in the West and I think, in a way, he could live with it but she couldn’t”, Sean says. “I thought it’d be that they could finally have a life and that it would be a happy Hollywood ending”.

The film is all the more affecting – and all the sadder – for this ending. With divorce rates in Syria spiking and divorce among refugees incredibly common, Syrian Love Story also points to a documented truth about the pressure placed on those whose relationships have to survive displacement. Today, Amer remains with his family in France. He has a new girlfriend but he struggles to love her in the way he loved Raghda.

Raghda, still a revolutionary, works for the opposition party in Turkey. She also has a new boyfriend. “When I go to see her in Turkey, she’s sat in a room with a bit of a wine, a fag, a computer and a bit of food and it’s like a prison”, Sean tells me. “She can never get out of prison… you are the prisoner of your past, perhaps”.

Syrian Love Story has a preview at the BFI Southbank on 15 September. It is released in select cinemas and on BFI Player on 18 September.

Credits

Text Oscar Rickett