This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Earthwise Issue, no. 353, Fall 2018.

Barry Keoghan politely interrupts our conversation to get the waitress’s attention. He asks for an iced coffee, but the waitress stares blankly back at him, before telling him they don’t serve that. It definitely is on the menu, but such is the thickness of Barry’s Irish accent, it takes a few repetitions of the word “iced” before the penny drops. “Where was I?” he says, returning to the question. “My mother…”

Barry is referring to the drug overdose that took his mum’s life when he was just 12 years old. The question ‘How did your mother’s death affect you?’ is one Barry has likely had to answer with galling repetition over the last few months. But, as he’s the first to recognise, it’s part of a backstory that isn’t typical of many young actors in Hollywood today, and one that shouldn’t be overlooked. “I come from a different world,” Barry says. “Her death shaped who I am, definitely, but it’s something that’s affected a lot of families back home. I definitely don’t put myself in a box. Everyone has an experience that I know nothing about.”

Barry grew up in inner-city Dublin, in the true heart and soul of the city, “the part where the character of Dublin lies,” he says, smiling at the mention of home. For much of his childhood Barry and his brother Eric moved between different foster care homes, his mother a victim of the opiate epidemic that hit Dublin hard during the 90s. “She wasn’t able to handle us, she was very sick.” When she passed away they moved in with their aunt and grandmother. “Drugs affect a lot of families. Mine was a family that was affected by it. You take it on the chin, you know? But my brother and I are probably the closest brothers you’ve ever seen.”

An amateur boxer and a self-described “messer” at school, it wasn’t until spotting a call-out for actors placed in a local shop window that Barry put himself up for his first role, aged 17. “I saw it in a window — an open invitation, street cast, and I saw there was time off school. It was a small movie. But I was like, ‘I can do this!’” A few months later, the director got in touch after finding funding for the film, and so came Barry’s first credit; Aido in the crime drama Between the Canals.

Dropping out of school not long after, Barry rebuffed the inevitable cynicism his friends had towards his new ambition of becoming an actor. “I said ‘I don’t need school… I can do acting’, and people were like ‘yeah, yeah… we’ll be singers! Or soccer players!’” But the same director came back with another role, and a string of varied and celebrated roles in Irish films and TV series followed. From picking up a credit as a young Dublin lad in King of the Travellers to playing the baby-faced, dead-eyed, cat-killing Wayne in crime series Love/Hate, Barry quickly became one of Ireland’s most prodigious young talents. But it was in 2017 that he broke through to new levels of stardom.

First came the role of George, a gentle, good-hearted teenager involved in a civilian rescue mission for Christopher Nolan’s World War II epic, Dunkirk. “A dream come true,” and enough to put him on the Hollywood agenda for a quick second. But in the expeditiously-fast cycle of new actors rising up, touted as The Next Big Thing — Barry needed more weight behind him than just one part of a large ensemble cast. Then came the role of Martin in Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Killing of a Sacred Deer. Arguably one of the most fascinating and malevolent cinematic roles in recent memory, Barry not only rose to the challenge, but carried Yorgos’s vision to victory.

Martin is introduced as the unusual, persistent friend of Colin Farrell’s lead, Steven — a cardiovascular surgeon and patriarch of a wealthy nuclear family in the suburbs. Why and how the pair have become friends is not initially clear, but a tenebrous atmosphere between the two can soon be felt. When Martin’s demands to see him become too frequent, Steven begins to retreat. Not long after, Steven’s son falls victim to an unknown illness that slowly begins to paralyse his body. Martin reveals to Steven he knows his negligence as a surgeon caused his father’s death, and is now exacting revenge on him. Each of his family will succumb to the same illness — paralysis, starvation, bleeding from the eyes, death — unless Steven chooses one of them to sacrifice.

Beyond the chaos that Martin’s violent ultimatum descends into, there’s one scene that remains lodged in the mind long after the film finishes. Martin, sitting in a T-shirt and pants, gorging on a plate of spaghetti rested on his thighs, as the mother of Steven’s children — played by Nicole Kidman — pleads with him to have mercy on her family. Completely unfazed, eyes unforgiving, words delivered with total detachment from her pain, Martin continues to shovel thick lumps of pasta into his mouth. “Tapping into things… I don’t even know what I’m tapping into,” he says, discussing what it takes to reach that place. “That’s the scary thing about acting — the thing that can fuck with your head — going into these places. Martin is a far darker character than I am, but I was definitely going somewhere.”

Contemplating such darkness, day in day out, can be quite hard to break out of. “You give so much time to your characters. It’s therapeutic, but it brings a lot of stuff up. You’re constantly going through these emotions. The way I work, I’m constantly going through these feelings, shifting gears — it definitely affects the mind.”

That’s when you get the part. What about the mental drain of working towards a role that you don’t end up winning? “That messes with your head, when you don’t get a part. You start questioning yourself, ‘Am I not good enough?’ It’s really draining, mentally draining. It takes me about a day, and then I get back up on my feet and I’m good again. My girlfriend Shona — she does all my tapes, she gets me back on my feet. Recently I did get down about one role I didn’t get, and she just knocked it out of me. She was just like, ‘Come on, back up on your feet’. You need someone to do that for you.”

Next up, Barry will play one of four students who attempted to steal a collection of rare books from their college library in Bart Layton’s highly buzzed, true story adaption of American Animals — a role he brings a thoughtful, intelligent sensitivity to — and the titular Yorick in an adaption of DC Comic Y: The Last Man. In terms of a vision for himself over the next few years, Barry is approaching his next steps with the precision and focus of a man who knows exactly what he wants. He wants to work with more of the directors listed in his iPhone notes (Yorgos, Christopher, Bart – check) and plans to start bulking up, physically, so he can be considered for older roles. “I don’t look like your typical leading man, especially after The Killing of a Sacred Deer, playing a psycho, people now associate me with that. So it’s a strategy thing. Every choice is a strategic choice.”

Strategy aside, Barry is keen to keep his feet on the ground, and not succumb to the untoward aspects of fame. “One thing that’s really opened my eyes is just how interested people are in me now. I always ask the question, ‘Would you be that interested if I wasn’t on screen?’ It’s crazy, especially coming from people who didn’t know me before. Now they spot me on the street and they’re suddenly interested in… what colour socks I have on.” It doesn’t seem very likely, then, that Barry will forget his roots. “I wouldn’t be allowed to, with my granny beside me, she’d give me an awful smack!”

Credits

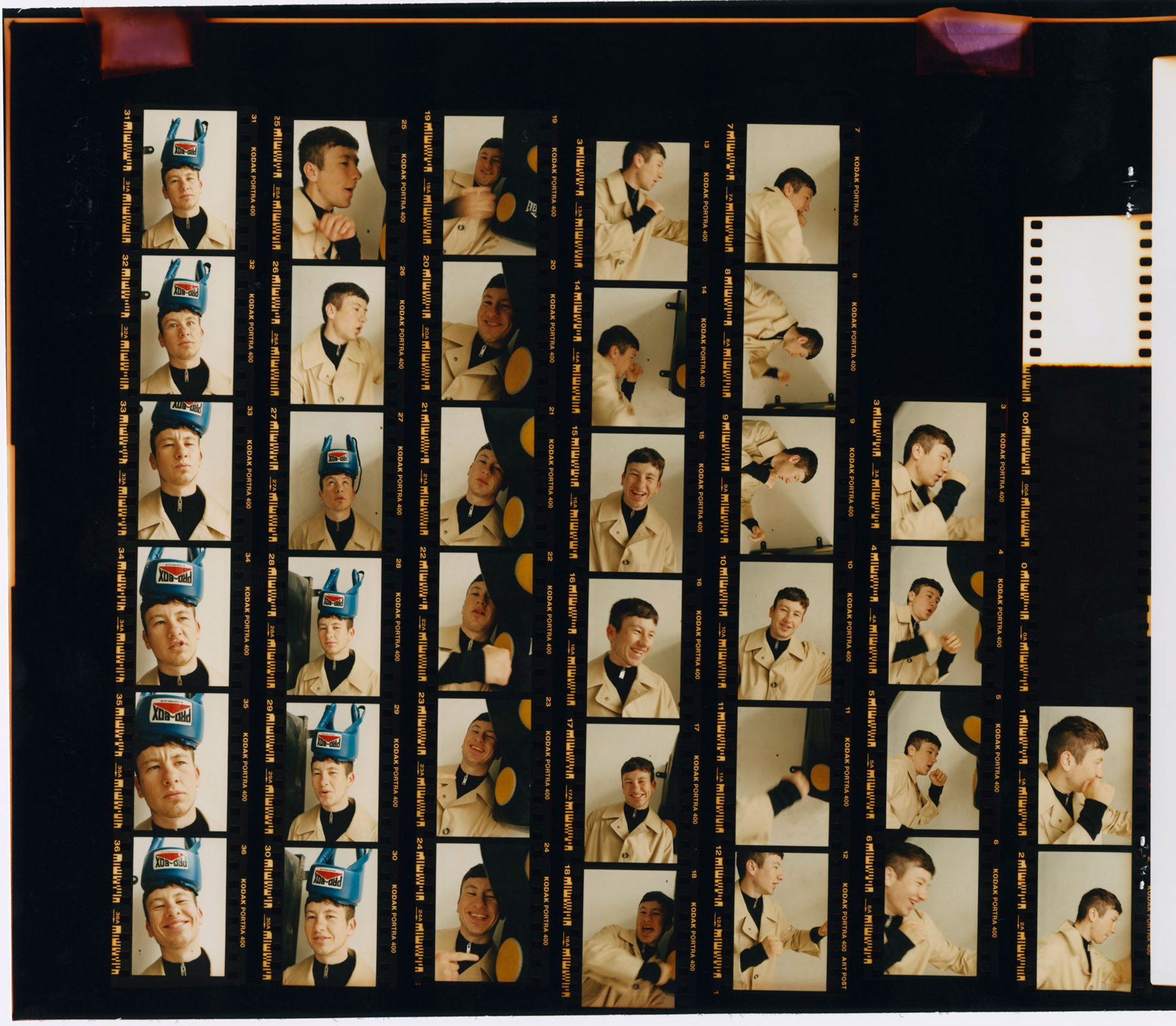

Photography Eddie Wrey

Styling Max Clark

Hair Mark Hampton at Julian Watson Agency using Fatboy Hair. Photography assistance Nicola De Cecchi and Sam Henry. Styling assistance Louis Prier Tisdall.