“I’m a great fan of art,” Michael Jackson told Oprah Winfrey in 1993. “I love Michelangelo. If I had the chance to talk to him or read about him, I would want to know about what inspired him to become who he is – the anatomy of his craftsmanship”. This quote is one of the first things you see in the National Portrait Gallery’s blockbuster new exhibition Michael Jackson: On The Wall. It’s followed by a flash of naivety from Jackson: “Not about who he went out with last night, or why he decided to sit out in the sun so long….” While Jackson still haunts so much of popular culture — from the obvious aping by popstars that followed to the smaller details (Troye Sivan’s billowing shirt in his My My My video, for example) — his perfectionism, ego and that dichotomy between entertaining millions and shying away from the public eye, meant he connected closely with titans from the art world.

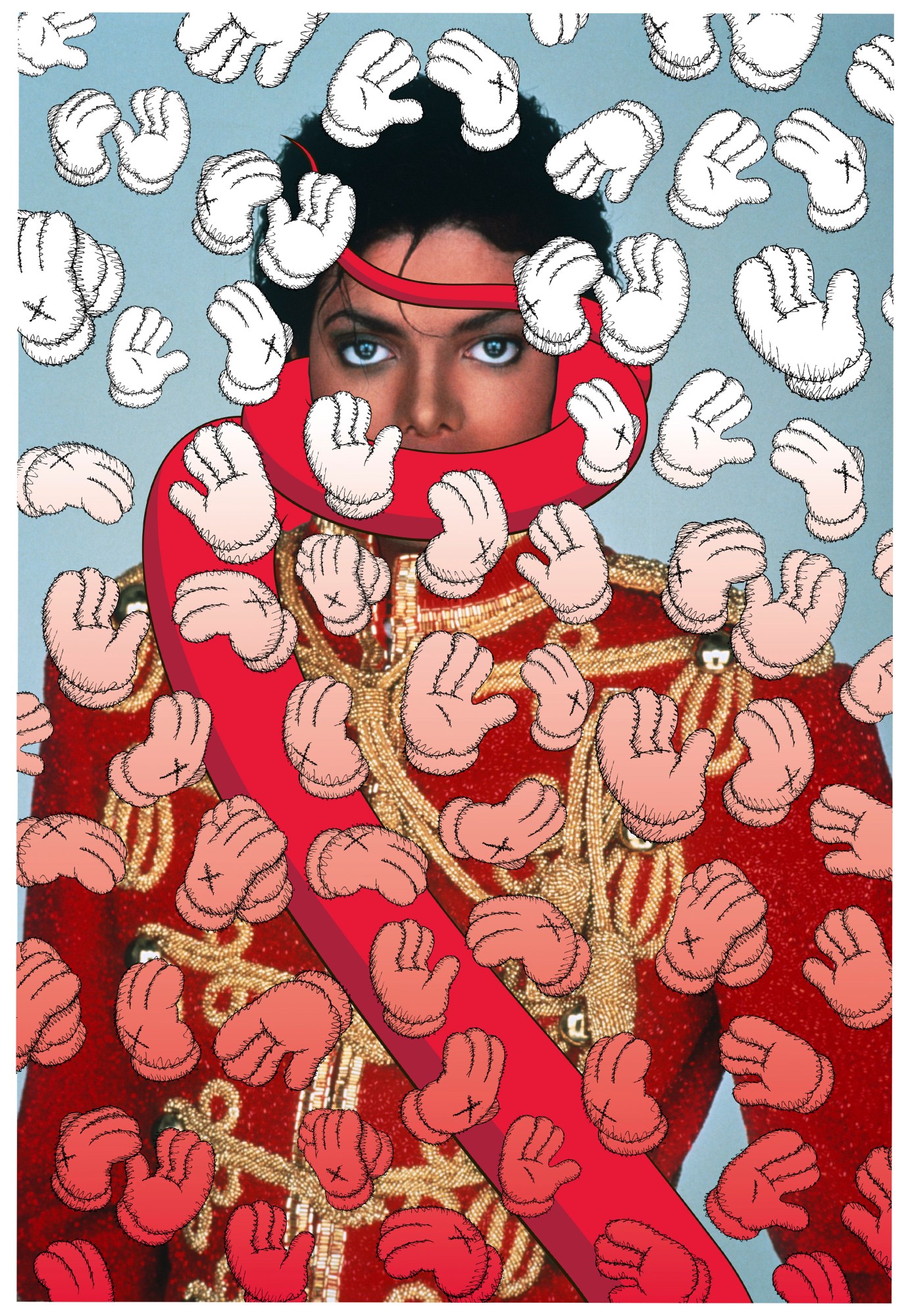

Featuring works by 48 contemporary artists, including David LaChapelle, Keith Haring, Maggi Hambling and Grayson Perry, this exhibition aims to make that relationship reciprocal. This isn’t a nostalgic, chronological skip through his career, a la the ABBA Museum or that Prince one at the O2 — all old stage outfits and interactive singalongs. Instead, Jackson’s multifaceted identities are refracted through various impressionistic prisms; one room explores his image as an African-American, for example, with photographer Todd Gray obscuring and disrupting his own photos of Jackson and asking the audience to re-evaluate how they see black bodies. Warhol’s silkscreen images that were used for a Time magazine cover, meanwhile, freeze Jackson at his Thriller-era pomp, encapsulating a shared history of one of the world’s most recognised faces. Reflecting how we see ourselves in the world through public figures and idols, Glenn Ligon’s Self-portrait at Seven Years Old isn’t that at all, but is actually a delicate etching of the young Michael Jackson.

In fact, Jackson’s face, which had morphed from wide-eyed child star escaping poverty in Indiana to the monster mask of a man who’d literally built his own Neverland to hide away in, looms large. His eyes dominate, peering out onto a Hieronymus Bosch-esque carnivalesque unreality via Mark Ryden’s Dangerous artwork (turned into a huge, ceiling-high doorframe here), or looking haunted and lost in Gary Hume’s 2001 painting, Michael. One piece even has his eyes painted onto a cushioned headboard. Elsewhere that criticised and manipulated face is dissected further. In Mark Flood’s photocollage Michael and ET Jackson’s broad grin is stretched out until it mirrors that of his alien friend, reflecting how the musician felt a connection with Spielberg’s creation. “He’s in a strange place and wants to be accepted,” he told Ebony in 1982. “He gives love and wants love in return, which is me.” Perhaps the most evocative picture is Hank Willis Thomas’s Time Can Be a Villain or a Friend, which is based on an Ebony feature from 1984 imagining what Jackson would look like in the year 2000. The title is taken from the photo’s caption in the magazine, with the accompanying text surmising Jackson will have aged gracefully. It’s like an idealised photo-fit, before he Frankenstein-ed his identity to escape himself.

The exhibition’s calling card, however, is Kehinde Wiley’s Equestrian Portrait of King Philip II (Michael Jackson), a floor-to-ceiling sized cod-classicist portrait commissioned by Jackson himself shortly before he died. Inspired by Rubens — who Jackson was a huge fan of — it depicts him on horseback in full armour, overlooking a battle and surrounded by cherubs. It is brilliantly, almost hilariously, gaudy, but perhaps says the most about the man himself. Unlike LaChapelle’s photos depicting Jackson in a number of Biblical settings, or Lorraine O’Grady’s pretentious The First and Last of the Modernists in which Jackson is compared to 19th century French poet Charles Baudelaire, Wiley’s piece is a reflection of how Jackson saw himself, and, in turn how he wanted to be seen and remembered. Like so much of Jackson’s life and career, it’s breathtaking in its audacity.